Полная версия

Exploring evaluative, emotive and persuasive strategies in discourse

(27)“He continually lived in impatient anticipation of something his brain was sure to produce” (ETrans_ESS_004)

(28)“[…] Vivía siempre a la expectativa, más bien impaciente, de algo que iba a surgir en su cabeza” (SO_ESS_004)

As for the subtypes of Expansion and Contraction, the chi-square test yields no significant distributional differences in any of the cases; this result partially confirms the first hypothesis. However, it must be noted that Contraction shows the dissimilarity that Proclaim and Disclaim are more common in the English and Spanish texts, respectively.

Table 3. Distribution of the Engagement spans by major categories in the English and Spanish texts (originals and translations)

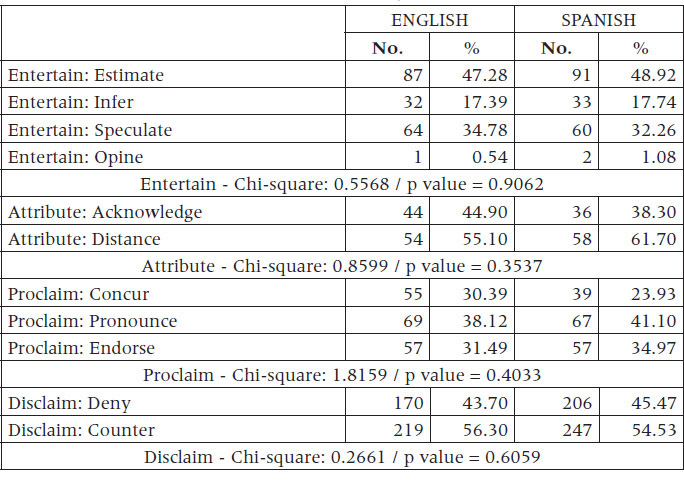

With regard to the more delicate categories (see Table 4), the chisquare test yields no significant differences either. Concur is slightly more frequent in the English texts, due above all to the occurrences of of course (totalling 8), which are sometimes not translated, as may be seen in (29) and its translation (30).

Table 4. Distribution of the Engagement spans by delicate categories in the English and Spanish texts (originals and translations)

(29)These are among the issues I shall be attempting to address in this book. To ask for definitive answers to such grandiose questions would, of course, be a tall order. (EO_EXP_015)

(30)Éstas son algunas de las cuestiones que intentaré tratar en este libro. Pedir respuestas definitivas a preguntas tan fundamentales estaría fuera de lugar. (STrans_EXP_015)

The two subcategories of Disclaim, on the other hand, are more common in the Spanish texts than in the English texts. The difference in Deny is due to the fact that in Spanish the number of negative expressions is sometimes higher: in (31), coordination of two negative clauses is expressed by means of ni (‘nor’), while in English this coordination is often achieved by or, as may be seen in its translation (32):

(31)For the most part I will try not to advocate particular policies or to advance the agenda of the political left or right. (EO_EXP_020)

(32)En gran parte intentaré no defender unas políticas concretas ni promover la agenda de la derecha o la izquierda. (STrans_ EXP_020)

As for Counter, the larger number of occurrences in the Spanish texts uncovers the fact that the Spanish translations sometimes make this meaning explicit, for the sake of clarity, even if it is implicit in the originals. For example, the original fragment cited in (33) has no explicit Counter device; however, pero (‘but’) is included in the translation (34).

(33)The Earth is a place. It is by no means the only place. (EO_ EXP_002)

(34)La Tierra es un lugar, pero no es en absoluto el único lugar. (STrans_EXP_002)

6.3 COMPARISON OF THE ORIGINAL ENGLISH AND SPANISH TEXTS

The distribution of the main Engagement expressions in the original English and Spanish texts is specified in Tables 5 and 6. Both

Table 5. Distribution of the Engagement spans by major categories in the original English and Spanish texts

Table 6. Distribution of the Engagement spans by delicate categories in the original English and Spanish texts

Expansion and Contraction are more common in the English texts but, as Table 5 shows, there are no significant differences in the relative frequencies of the English and Spanish texts. On the other hand, the differences in the distribution of the subcategories of Expansion and Contraction are significant. As for the more delicate level of subcategories, Table 6 shows that the distributional differences are significant for Attribute and Proclaim, but not for Entertain and Disclaim.

The expressions of Entertain in the English originals more than triple those of the Spanish originals. In spite of the non-significance in the distribution of the subtypes, it is worth mentioning that the English expressions of Estimate are almost four times as frequent as the Spanish ones. The English writers were thus more prone to express statements with a weak degree of probability: the most common expressions are the modal auxiliary may in its epistemic sense (9 occurrences), the adjective likely (7 times) and the adverb perhaps (6 times); other expressions, such as might or the noun risk also appear several times. In the Spanish texts, however, the adverb quizá/quizás (‘perhaps, maybe’) only appears twice. As for Infer, the expressions in the English texts more than double those in the Spanish texts. The verb seem occurs 5 times; curiously, its synonym appear occurs only once. In the Spanish texts, the close equivalent parecer does not occur at all.

In contrast to Entertain, Attribute is more common in the Spanish originals. Acknowledge is more frequent in the English texts, but the expressions of Distance in the Spanish texts more than triple those of the English texts; a reason for this may be that a large part of the Spanish expository texts concern history and contain citations of ancient sources of information such as Marco Polo, prestigious in their time but now unreliable because of modern knowledge (see example 19 above). In addition, and more importantly, the authors of the Spanish argumentative texts tend to cite more information from unreliable sources (and later refute it), as in (35), whose translation is quoted in (36):

(35)En la crisis financiera de 2008, la creencia de que los riesgos se pueden calcular, asegurar y vender a otros incitó a asumir más riesgos. (SO_ESS_001)

(36)In the financial crisis of 2008, the belief that risks could be calculated, insured and sold on to others incited dealers to take on even more risks. (ETrans_ESS_001)

Concerning Contraction, the number of expressions of Deny is virtually equal in the texts of the two languages, while Counter is more common in the English texts. If we consider that the cases of Counter are more frequent in all the Spanish texts than in all the English texts, we can infer the importance of the tendency of Spanish translations to use cohesive devices even if they are not used in the originals, pointed out in 6.2. and exemplified with (33) and (34) above. That is to say, this higher explicitness of adversative or concessive relations seems to be a feature of Spanish translations compared to the original English texts, but this feature is not seemingly due to a tendency of Spanish written discourse to signal these relationships more explicitly than English written discourse. Research on cohesion along these lines would be welcome.

6.4 COMPARISON OF THE ARGUMENTATIVE AND EXPOSITORY TEXTS

The distributional differences in the number of Expansion and Contraction devices in the argumentative and expository texts are yielded by the chi-square test as significant (see Table 7), the main difference being that Expansion is more frequent in the expository texts, while the expressions of Cited-expansion, although they are few altogether, are more than twice as common in the essays. That is to say, the essays display more cases of dialogic acknowledgement of alternative positions through reference to other sources. The percentages of Contraction are almost identical in the two subtypes. Noticeably, the relative percentages of Expansion and Contraction present in both essays and expository texts are similar to those registered for English and Spanish professional and consumer-generated film reviews in Carretero (2014: 77), which were 34.95 for Expansion and 65.05 for Contraction. These data together hint that, in non-fictional texts aiming at transmitting information and/ or persuading the reader, typically the occurrences of Contraction roughly double those of Expansion.

Table 7 also shows that the distributional differences between the main categories of Expansion and Contraction are significant. In particular, Proclaim is markedly more frequent in the argumentative texts, while Entertain is more common in the expository texts, which is not surprising due to the greater need of the writers of essays to defend their dialogic position. The distribution of the most delicate subtypes, given in Table 8, indicates that the differences are significant for the subcategories of Contraction (Proclaim and Disclaim) but not for the subcategories of Expansion (Entertain and Attribute).

Table 7. Distribution of the Engagement spans by major categories in the argumentative and expository texts (originals and translations)

Table 8. Distribution of the Engagement spans by delicate categories in the argumentative and expository texts (originals and translations)

With regard to Contraction, the occurrences of Concur are almost equal in the two text types, while Pronounce and Endorse are more frequent in the argumentative texts. That is to say, the support of dialogic position is most commonly realised by emphasising one’s own viewpoint (Pronounce) or by supporting the position by authoritative or prestigious sources (Endorse). With regard to Disclaim, it is globally more common in the expository texts; the cases of Counter are virtually the same for the two registers, but the expository texts display more cases of Deny, which often refer to a contrast between people’s beliefs and the way things actually are, as in (37), a fragment that contains eight instances of this category:

(37)It is natural but wrong to visualize the singularity as a kind of pregnant dot hanging in a dark, boundless void. But there is no space, no darkness. The singularity has no “around” around it. There is no space for it to occupy, no place for it to be. We can’t even ask how long it has been there—whether it has just lately popped into being, like a good idea, or whether it has been there forever, quietly awaiting the right moment. Time doesn’t exist. There is no past for it to emerge from. (EO_ EXP_001)

With regard to Expansion, although the distribution of the subcategories in Entertain and Attribute is not significant, attentive observation leads us to note that the higher frequency of Entertain in the expository texts is largely due to the difference in number of Estimate devices, which is also related to the main difference in the overall purposes of the texts. Estimate expressions tend to weaken the writer’s assertiveness and this weakening is more at odds with the persuasive purpose of argumentative texts than with the informative purpose of expository texts. The high frequency of Speculate in both text types is plausibly due to the intellectual character that they share: writers often pose complex questions with no obvious answers, as in examples (8-9), in order to trigger reflection and then propose answers through reasoning.

7 Final Discussion and Concluding Remarks

This paper has set forth a quantitative study of the Engagement expressions in 40 argumentative and expository texts, consisting of English and Spanish originals and their corresponding translations into the other language. I acknowledge that the study has limitations concerning the accuracy of the labels assigned to the expression of Engagement, mainly because all the texts were analysed by the author of the paper: the analysis of the same texts by one other researcher (or more) and the ensuing comparison of the results would have been an extra tool for detecting possible errors, and the cases of disagreement would have led to an increase in the refinement of the criteria for assigning expressions to the different categories. Nevertheless, as its stands, the analysis may be considered to be sufficiently reliable for proving the hypotheses stated in Section 3.

The first hypothesis, namely that the expressions under study were faithfully translated to a great extent, has been partially disconfirmed by the significant distributional differences found in the major Engagement categories (Expansion, Contraction, Cited-expansion and Cited-contraction) in the English and Spanish texts. The main reason was that the Spanish translations sometimes added explicit Counter expressions that were absent in the English originals. This finding, together with the higher frequency of Counter expressions in the original English texts than in the original Spanish texts, lead us to believe that the Spanish translations of non-fictional texts had a tendency to overspecify cohesion, an issue that could be pursued in further research. On the other hand, this hypothesis has been partially confirmed by the absence of significant differences in the distribution of the main types of Expansion and Contraction and of all the subtypes of these categories.

The second hypothesis, which stated that differences would be found in the English and Spanish originals, has also been partially disconfirmed by the distribution of the main Engagement categories, but partially confirmed by the distributional differences found in all the subcategories of Expansion and Contraction, and especially in the subtypes of Attribute and Proclaim. The English originals display more cases of Entertain, especially of the subcategories Estimate and Infer.

The third hypothesis, namely that the distribution of Expansion and Contraction in argumentative and expository texts would differ due to the overall aims of both texts, has been confirmed by the results in terms of both the main categories and their subtypes: not surprisingly, Expansion was more common in the expository texts, which aim above all to transmit knowledge, and Contraction in the argumentative texts, where the need to persuade the reader is greater.

This study provides evidence of the crucial role of the expressions of Engagement in persuading the reader that the writer’s assessment is the most sensible within the array of actual or potential viewpoints. The need to be persuasive is more obvious in the essays, but is far from being non-existent in the expository texts. This persuasive role of Engagement may be noticed in many of the examples cited in this paper, such as (15), (16) and (37), to name only a few. Engagement, then, may be considered to offer a privileged perspective on the pervasive relation between persuasion and evaluation in language.

Further research on Engagement in different types of non-fictional texts, especially from parallel corpora, could be carried out in order to shed light on the extent to which the main findings presented here could be extrapolated to other types of non-fictional texts. If we begin by comparing the results presented here with those of Carretero’s (2014) study on film reviews, we find that the three categories that involve citation of a source of information, namely Acknowledge, Distance and Endorse, are markedly more common in the texts analysed here; conversely, Counter is even more frequent in the film reviews, for the reason that critics are quick to communicate the ways in which expectations created by films are unfulfilled in order to warn prospective viewers (Carretero 2014: 76). These differences are one more illustration of how different subtypes of non-fictional texts create different needs for writers to assess their position against other possible positions with regard to the information transmitted and of how writers actually cope with these needs. That is to say, the relative frequency of the Engagement categories seems to vary according to the subtype of nonfictional text, depending on the writers’ assessment of the need to place emphasis on one category or other in order to legitimise their position or, in other words, to persuade the addressee that they are legitimate sources of information.

Acknowledgements

This research has been carried out as part of the EVIDISPRAG Project (reference number FFI2015-65474-P MINECO/FEDER, UE). We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the European Regional Development Fund. My thanks are extended to an anonymous referee for his/her thorough report on a first version of the paper. The remaining shortcomings and inconsistencies are my sole responsibility.

References

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination. Four Essays. (Translated by C. Emerson and M. Holquist.) Austin: University of Texas Press.

Carretero, Marta (2010). “‘You’re absolutely right!’: A corpus-based analysis of absolutely in British English and absolutamente in Peninsular Spanish, with special emphasis on the relationship between degree and certainty”. Languages in Contrast 10 (2), 194-222.

Carretero, Marta (2014). “The role of authorial voice in professional and non-professional reviews of films: An English-Spanish contrastive study of Engagement”. In Gil-Salom, Luz and Carmen Soler-Monreal (eds.) Dialogicity in Specialised Genres. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 55-85.

Carretero, Marta and Maite Taboada (2015). “The annotation of Appraisal: How Attitude and epistemic modality overlap in English and Spanish consumer reviews”. In Zamorano-Mansilla, Juan R., Carmen Maíz, Elena Domínguez and M. Victoria Martín de la Rosa (eds.) Thinking Modally: English and Contrastive Studies on Modality. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 249-269.

Carretero, Marta and Juan Rafael Zamorano-Mansilla (2013). “Annotating English adverbials for the categories of epistemic modality and evidentiality”. In Marín-Arrese, Juana I., Marta Carretero, Jorge Arús Hita and Johan van der Auwera (eds.) English Modality: Core, Periphery and Evidentiality. Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 317-355.

Hansen-Schirra, Silvia, Stella Neumann and Erich Steiner (2012). Cross-linguistic Corpora for the Study of Translations – Insights from the Language Pair English-German. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Langacker, Ronald W. (2009). Investigations in Cognitive Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lavid, Julia, Jorge Arús, Bernard DeClerck, and Veronique Hoste (2015). “Creation of a high-quality, register-diversified parallel (English-Spanish) corpus for linguistic and computational investigations”. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 198, 249-256.

Lavid, Julia, Marta Carretero and Juan Rafael Zamorano Mansilla. (2016). “A linguistically-motivated annotation model of modality in English and Spanish: Insights from MULTINOT”. Linguistic Issues in Language Technology 14, 1-35.

Lavid, Julia, Marta Carretero and Juan Rafael Zamorano Mansilla (2017). “Epistemicity in English and Spanish: An annotation proposal”. In Marín-Arrese, Juan I., Julia Lavid-López, Marta Carretero, Elena Domínguez Romero, Mª Victoria Martín de la Rosa and María Pérez Blanco (eds.) Evidentiality and Modality in European Languages. Discourse-Pragmatic Perspectives. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 241-276.

Lichtenberk, Frantisek (1995). “Apprehensional epistemics”. In Bybee, Joan and Suzanne Fleischman (eds.) Modality in Grammar and Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 293-327.

Marín-Arrese, Juana I. (2011). “Effective vs. epistemic stance and subjectivity in political discourse: Legitimising strategies and mystification of responsibility”. In Hart, Christopher (ed.) Critical Discourse Studies in Context and Cognition, ed. by Christopher Hart. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 193-223.

Martin, James R., and Peter R. R. White. (2005). The Language of Evaluation. New York: Palgrave.

Mora, Natalia (2011). Annotating Expressions of Engagement in Online Book Reviews: A Contrastive (English-Spanish) Corpus Study for Computational Processing. MA Dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, available at http://eprints.ucm.es/13754/ (Accessed 27 December, 2017).

Nuyts, Jan (2001). Epistemic Modality, Language and Conceptualization. A Cognitive-pragmatic Perspective. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Palmer, Frank R. (1990). Modality and the English Modals. London and New York: Longman.

Paulussen, Hans, Lieve Macken, Willy Vandeweghe, and Piet Desmet (2013). “Dutch parallel corpus: A balanced parallel corpus for Dutch-English and Dutch-French”. In Spyns, Peter and Jan Odijk (eds.) Essential Speech and Language Technology for Dutch. Springer: Cham, pp. 185-199.

Voloshinov, Valentin N. (1973). Marxism and the Philosophy of Language. (Translated by Ladislav Matejka and I.R. Titunik.). London: Seminar Press.

White, Peter R. R. (2002). “Appraisal”. In Östman, Jan-Ola and Jef Verschueren (eds.) Handbook of Pragmatics. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 1-27.

White, Peter R. R. (2015). An Introductory Course in Appraisal Analysis. Retrieved at

Appendix

References and URLs of the texts analysed:

EO_ESS_001: Joseph E. Stiglitz, “A Greek morality tale”, Project Syndicate, February 3, 2015.

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/greece-eurozone-austerity-reform-by-joseph-e--stiglitz-2015-02?barrier=true

EO_ESS_004: Laura Tyson and Saadia Zahidi, “The slow march to gender parity”, Project Syndicate, October 31, 2014.

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/closing-gendergap-economic-participation-by-laura-tyson-and-saadia-zahidi-2014-10?barrier=true

EO_ESS_005: Michael J. Boskin, “A five-step plan for European prosperity”, Project Syndicate, February 25, 2015.

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/europe-prosperity-obstacles-by-michael-boskin-2015-02?barrier=true

EO_ESS_006: J. Bradford DeLong, “Making Do with More”, Project Syndicate, February 26, 2015.

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/abundance-without-living-standards-growth-by-j--bradford-delong-2015-02?barrier=true

EO_ESS_009: Nouriel Roubini, “Where Will all the Workers Go”, Project Syndicate, December 31, 2014.

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/technology-labor-automation-robotics-by-nouriel-roubi-ni-2014-12?barrier=true

EO_EXP_001: Bill Bryson, “How to build a universe”. A Short History of Nearly Everything. (Fragment). New York: Doubleday, 2003

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/18/books/chapters/0518-1st-bryson.html?pagewanted=all

EO_EXP_002: Carl Sagan, Cosmos. (Fragment). New York: Random House, 1980.

EO_EXP_003: Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, third edition. (Fragment). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

http://www.geoffwilkins.net/fragments/Dawkins.htm

EO_EXP_015: Roger Penrose, The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and the Laws of Physics. (Fragment). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

EO_EXP_020: Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate. The Modern Denial of Human Nature. (Fragment). London: Penguin, 2002.

ETrans_ESS_001: Daniel Innerarity, “Nostalgia for quiet passions”, 2011, translated by Peter J. Hearn.

http://www.essayandscience.com/article/30/nostalgia-for-quietpassions/,

ETrans_ESS_002: Víctor Gómez Pin, “Redention and the Word”, 2009, translated by Mike Escárzaga.

http://www.essayandscience.com/article/2/redemption-and-the-word/