Полная версия

Exploring evaluative, emotive and persuasive strategies in discourse

(14)According to fifteenth-century man, only 1,000 years remained before the purifying flames of the Last Judgment would destroy the world (ETrans_EXP_003)

2.2.2 Contraction

Contraction differs from Expansion in that, even if it also admits the existence of alternative positions, “the utterances challenge, fend off or restrict the scope of the alternative positions and voices” (Martin and White 2005: 102). That is to say, the writer supports only one of these positions. Expressions of Contraction are used when the writer feels the need to lay emphasis on commitment to the truth of the information that s/he is transmitting because it is not obvious to others and hence challengeable. Therefore, Contraction seems out of place when there is no room for challenge: for example, certainly would be odd in I’m certainly wearing a green coat in a face-to-face conversation. Contraction is divided into two subtypes: Proclaim and Disclaim.

The subcategories of Proclaim are Concur, Pronounce and Endorse. Concur “involves formulations which overtly announce the speaker / writer as agreeing with, or having the same knowledge as, some projected dialogic partner”. (Martin and White 2005: 122). That is, the statement is presented as agreeing with, or having the potential to agree with, the majority of voices. Expressions of Concur include adverbials that express agreement with previous expectations (of course, naturally, not surprisingly, admittedly…), strong evidential expressions such as clear, evident, obvious and the derived adverbs, and other ways of indicating agreement with other opinions (as everyone knows, it is well-known that, it is acknowledged that, no-one would deny that…), as well as the Spanish equivalents of these expressions. Concur also includes those expository questions that assume an obvious answer (Martin and White 2005: 123), such as (15) and its Spanish translation (16):

(15)Does anyone in their right mind think that any country would willingly put itself through what Greece has gone through, just to get a free ride from its creditors? (EO_ESS_001)

(16)Alguien en su sano juicio cree que algún país estará dispuesto a atravesar voluntariamente lo que Grecia ha tenido que atravesar, sólo por conseguir ventajas de sus acreedores? (STrans_ ESS_001)

The second subtype of Proclaim, Pronounce, “covers formulations which involve authorial emphases or explicit authorial interventions or interpolations” (Martin and White 2005: 127). That is, the author expresses that his/her opinion is firm, without referring to other opinions. Realisations of Pronounce include emphatic affirmation, expressions of epistemic certainty (certainly, definitely, really, surely, for sure…), lexical verbs referring to speech acts or mental states of certainty, in the first person (I know, I say…), other expressions which insist that the facts are real (the fact is that…), and even parallelisms or repetition of words.

The third subtype, Endorse, “refer[s] to those formulations by which propositions sourced to external sources are construed by the authorial voice as correct, valid or undeniable or otherwise maximally warrantable” (Martin and White 2005: 126). Endorse resembles Attribute in that an external source is mentioned, but in this case the writer supports only the position expressed by the source, thus expressing high commitment to the information transmitted. Expressions of Endorse include verbs such as show, prove, demonstrate, find or point out with different persons from the first.

The Disclaim category challenges some contrary position, by openly rejecting it or by positioning itself at odds with it. Its subcategories are Deny and Counter. Deny consists in the overt negation of a proposition. Cases in which negation affects only part of the clause, as in (17), have also been included, since the writer’s intention is still to reject the idea that Greece should bear the consequences. Verbs with negative meaning such as lack, fail or neglect have also been considered as cases of Deny, following Mora (2011: 65).

(17)If Europe has allowed these debts to move from the private sector to the public sector – a well-established pattern over the past half century – it is Europe, not Greece, that should bear the consequences. (EO_ESS_001)

The other subcategory, Counter, “includes formulations which represent the current proposition as replacing or supplanting, and thereby ‘countering’, a proposition which would have been expected in its place” (Martin and White 2005: 120). In short, this category concerns counter-expectation. Among the many realisations of Counter, the most frequent are conjunctions and connectives of contrast such as although, however, yet, but, adverbials such as even, only, just, still, already or yet, and the Spanish equivalents of all these expressions. Counter also includes the adverbials actually and in fact and Spanish correlates such as en realidad or de hecho.

3 The Research Hypotheses

Before embarking on the actual Engagement analysis of the texts, three hypotheses were set. The first was that expressions of Engagement tend to be faithfully translated; in order to check this hypothesis, the texts analysed (see Section 4) include English and Spanish originals and their translations. A corollary of the first hypothesis was the second hypothesis, namely that a comparison including only the original texts in both languages would show greater differences: the English and Spanish essays would tend to favour the use of language-specific preferred devices. The third hypothesis was that the distribution of Engagement expressions would differ depending on text type: Contraction expressions could well be more numerous in the argumentative texts, since the writer has a greater need than in expository texts to defend his/her position against other possible alternatives; by contrast, Expansion devices might well be more common in the expository texts to signal limitations of the present state of knowledge. These hypotheses will be tested by comparing the data in the ways specified in Section 4.

4 The Data, Software and Method

The texts analysed here were extracted from the MULTINOT corpus, which consists of original and translated texts in both directions and is designed as a multifunctional resource to be used in different disciplines, such as corpus-based contrastive linguistics, translation studies, machine translation, computer-assisted translation and terminology extraction. The MULTINOT corpus, described in more detail in Lavid et al. (2015), includes a wide range of registers from the written mode, following typologies used in other parallel corpus projects, such as the DPC corpus (Paulussen et al. 2013) and the CroCo Corpus (Hansen-Schirra et al. 2012). The registers included are the following: novels and short stories; news reporting articles; manuals and legal documents from webpages; official speeches and proceedings of parliamentary debates; annual reports and letters of self-presentation of companies, promotion and advertising brochures; scientific texts; essays; and popular science expository texts.

The data chosen for analysis were 40 texts belonging to the last two categories: 20 essays and 20 popular science expository texts. The essays were written in the 2000’s, and the expository texts from 1980 onwards. The texts were also evenly divided according to the criteria of language (20 English and 20 Spanish) and originality (20 are original texts, and 20 are their translations).

The references and URLs of all the texts are specified in the Appendix. The argumentative texts are political essays on economics; the English originals were extracted from the non-profit international organisation Project Syndicate, which publishes and syndicates opinion articles on topics such as global affairs, economics, finance and development, and has members in many countries around the world. This organisation also provides the Spanish translations. The Spanish argumentative originals were extracted from the quality newspaper El País, and their translations were downloaded from the URL ‘Essay and science’, a webpage aimed at spreading original essays written in Spanish. The English and Spanish argumentative essays sometimes include short biographical notes about the authors. These parts were excluded from the analysis, since they lie outside the texts proper. The English and Spanish expository texts were extracted from highquality books by prestigious authors and publishers, aimed at the dissemination of knowledge in the areas of science and social science.

Many of the texts contain 1,000 words approximately; the others were cut after the paragraph to which the 1000th word belonged, so as to maintain a balanced number of words. Therefore, the 40 texts analysed amount to approximately 40,000 words.

The quantitative analysis was carried out with the aid of the UAM Corpus Tool, a free tool created and regularly updated by Mick O’Donnell at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.4 The choice of this software was due to its systemic-functional orientation, which makes it adequate for designing systems of options that serve as the basis for quantitative analyses.

In order to test the hypotheses, a threefold comparison of the expressions of Engagement was carried out:

a.All the English texts (originals and translations) versus all the Spanish texts;

b.The original English texts versus the original Spanish texts;

c.The argumentative versus the expository texts.

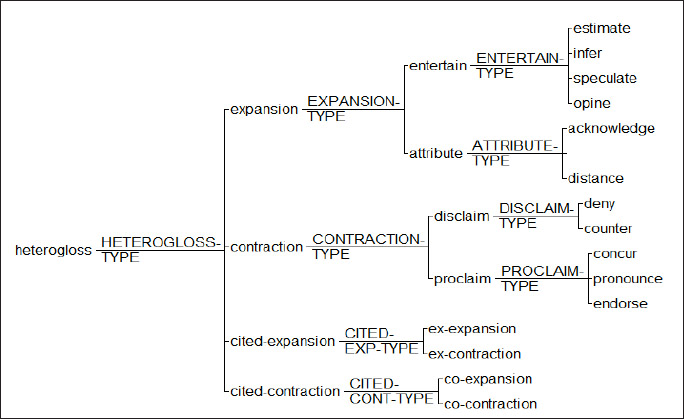

While performing the analysis, a problem was posed by the expressions of Engagement attributed to other sources, cited by means of direct or indirect reported speech or in some other way, which do not reflect the writer’s dialogic position. In order to register these cases, two new categories were created: a distinction was made between the cases in which the writer subscribes to the cited source (‘Cited-Contraction’) or else does not consider it as completely reliable (‘Cited-expansion’). Each of these categories was in turn divided into Expansion and Contraction, depending on the dialogic position of the expression itself. Given the limited number of expressions of these categories, no further distinction was made between the subtypes of Expansion and Contraction. The resulting system is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The system of Engagement used in this paper

In order to clarify the actual signalling of the ‘Cited’ categories, let us consider (18) and (19):

(18)El cacique Tecum, al frente de los herederos de los mayas, descabezó con su lanza el caballo de Pedro de Alvarado, convencido de que formaba parte del conquistador: Alvarado se levantó y lo mató. (SO_EXP_004)

English translation: ‘The chief Tecum, leading the descendants of the Mayas, beheaded the horse of Pedro de Alvarado with his lance, convinced that it was part of the conquistador: Alvarado stood up and killed him.’ (ETrans_EXP_004)

(19)For example, research finds that women tend to be less confident and less likely to negotiate for pay rises and promotions than equally qualified men. (EO_EXX_004)

Convencido in (18) and its correlate convinced are classified as ‘Cited expansion’, since the writer does not consider the chief Tecum as a valid source of information, and the subcategory is ‘Ex-contraction’, since Tecum is portrayed as having a firm belief. By contrast, in (19) the writer expresses alignment with the cited source, research finds, and the expression less likely expresses Expansion, thus being qualified as “Cited contraction: Co-expansion”.

5 Analysis of Unclear Cases

The system of Engagement, described in Section 2.2., provides a clear definition of subcategories and a number of sample realisations of each; however, given that the boundaries of Appraisal categories are context-dependent and inevitably not clear-cut, cases were found where categorisation was not easy. To start with, the realisations of the different categories were sometimes more complex than the standard realisations; for instance, some examples of Estimate are expressions with nouns that point to possibilities for future events to occur, as in “growth prospects are even worse” (EO_ESS_006), or “mi hipótesis de trabajo es la siguiente” (SO_ESS_004), translated as “my working hypothesis is the following” (ETrans_ ESS_004). Even a seemingly easily detectable category such as Counter, often realised by expressions such as however, although or yet, displayed instances where the realisation was rather more complex, such as (20), where the Noun Phrase headed by paradoxes indicates a contrast between a circumstance (‘in a time…’) and the rest of the proposition expressed by the that-clause.

(20)One of the great paradoxes of our time is that workers and middle-class households continue to struggle in a time of unparalleled plenty. (EO_ESS_006)

Another problem was posed by the modal auxiliary will referring to future time. As is well-known (a sample reference is Palmer (1990)), there is disagreement among scholars about whether it expresses a ‘pure future’ or else its modal value is maintained in all the cases. In the present study, will has been considered as a case of Pronounce, since in the texts studied here it mostly expresses speculative predictions, as in (21), rather than ‘safe’ predictions such as ‘My sister will be fifty next month’. However, will has not been signalled when it is falls under the scope of another Engagement expression; in these cases, it borrows the value of that expression. For example, will in (22) does not express Pronounce, since it falls under the scope of the weaker Estimate expression remains uncertain, and hence it has not been considered as an Engagement span.

(21)Addressing these problems will be difficult, but not impossible. (EO_ESS_005)

(22)But, unless the proper policies to nurture job growth are put in place, it remains uncertain whether demand for labor will continue to grow as technology marches forward. (EO_ ESS_009)

The remainder of Section 5 will concern two basic kinds of problems, treated in 5.1. and 5.2., respectively. The first concerns a number of linguistic devices that lie in between two subcategories of Engagement; the second pertains to the boundaries between Engagement and Attitude.

5.1 DOUBTFUL CASES BETWEEN TWO SUBCATEGORIES OF ENGAGEMENT

There are many cases in which a source of evidence is cited, but the way in which it is cited does not give explicit indications about the writer’s degree of commitment, so they could be classified under either of the two subcategories of Attribute (Acknowledge and Distance) or under Endorse. A typical example of these ambivalent expressions are English according to and its Spanish equivalents de acuerdo con and según. In order to determine the writer’s attitude towards the source, the reliability (prestige or authority) of the source and the text as a whole have been considered. For example, the expression starting with según in (23) has been classified as Acknowledge, since another study is cited next and the writer does not show full commitment to either, while in (24), which belongs to the same text, the prestige of the source has motivated its classification as Endorse.

(23)Según un cálculo, a nivel mundial las mujeres ocupan alrededor del 24% de los puestos ejecutivos superiores. (STrans_ ESS_004)

English original: ‘By one estimate, women hold about 24% of top management positions globally’ (EO_ESS_004)

(24)Según datos del Foro Económico Mundial, hay una correlación importante entre los avances de un país en cuanto a cerrar la brecha entre los géneros – particularmente en educación y fuerza laboral – y su competitividad económica. (STrans_ ESS_004)

English original: WEF [World Economic Forum] data suggest a strong correlation between a country’s progress in closing the gender gap – particularly in education and the labor force – and its economic competitiveness. (EO_ESS_004)

Knowledge of the world may also play a role in expressions with the source cited. We know that Marco Polo’s appreciation of geography and raw materials was invaluable in his time but is now completely outdated. Consequently, the italicised expression in (25) has been classified as Distance:

(25)Out of Marco Polo’s sparkling pages leaped all the good things of creation: there were nearly 13,000 islands in the Indian seas, with mountains of gold and pearls and twelve kinds of spices in enormous quantities, in addition to an abundance of white and black pepper. (ETrans_EXP_003)

5.2 OVERLAPPING CASES BETWEEN ENGAGEMENT AND OTHER APPRAISAL CATEGORIES

This section covers cases in which there are arguments for considering the linguistic devices as instances of both Engagement and Attitude.5 The most remarkable overlapping cases are those that express uncertainty tinged with emotion, called ‘apprehension’ in Lichtenberk (1995) (see also Lavid et al. 2016, 2017). An expression of this kind is one hopes that in (26). These cases have the feeling component of Affect and the reasoning component of Engagement (Carretero 2014: 72). I have opted for including these cases as Estimate.

(26)One hopes that those who understand the economics of debt and austerity, and who believe in democracy and humane values, will prevail. Whether they will remains to be seen. (EO_ESS_001)

In other cases, Engagement was difficult to disentangle from Graduation, the main reason being that both categories concern the strengthening or weakening of assertiveness. In particular, certain adverbs that emphasise the extent to which the information is true, such as largely, completely or literally and their Spanish equivalents, belong to Focus: Sharpen but they have a similar effect to expressions of certainty such as certainly or undoubtedly, classified as Pronounce.6 This distinction has been maintained, thus keeping the two kinds of adverbs separate.

6 A Comparative Analysis of the Engagement Options in the Expository and Argumentative Texts

This section starts with a global characterisation of the Engagement expressions in all the texts, and then shows the results drawn from the comparisons in the three ways stated in Section 4: the English versus the Spanish texts, the original texts in the two languages, and argumentative versus expository texts. In all the cases, the significance of the differences was subjected to the chi-square test and, according to what is common practice in social science research, the difference was considered to be significant if the p value equalled or was smaller than 0.05.

6.1 A GLOBAL CHARACTERISATION OF THE ENGAGEMENT EXPRESSIONS IN ALL THE TEXTS

The distribution of the Engagement expressions in all the texts by categories is given in Table 2. Considering that the total number of words is approximately 40,000 words and that the total number of expressions is 1,860, the normalised frequency is 46.5 Engagement expressions per thousand words. Not surprisingly, the Contraction expressions double those of Expansion, due to the high frequency of the two categories under Disclaim: expressing negation or presenting the truth of a proposition as contrary to expectations are common devices in the use of language in general. The difference between Expansion and Contraction is even greater in the two categories of Cited expression categories, where Contraction exactly quadruples Expansion. Within Entertain, the most common category is Estimate, followed by Speculate, while Opine is almost non-existent: the authors did not adopt dialogic positions that indicated possibility for different individual judgements. In its turn, Attribute displays a higher frequency of Distance than of Acknowledge. Within Contraction, the distribution among the three types is roughly balanced, Pronounce and Concur being the most and the least common, respectively.

Table 2. Distribution of the Engagement spans in all the texts

No. % TOTAL NUMBER 1860 100 EXPANSION 562 30.22 CONTRACTION 1186 63.76 CITED-EXPANSION 60 3.23 CITED-CONTRACTION 52 2.80 EXPANSION ENTERTAIN 370 19.89 Entertain: Estimate 178 9.57 Entertain: Infer 65 3.49 Entertain: Speculate 124 6.67 Entertain: Opine 3 0.16 ATTRIBUTE 192 10.32 Attribute: Acknowledge 80 4.30 Attribute: Distance 112 6.02 CONTRACTION PROCLAIM 344 18.49 Proclaim: Concur 94 5.05 Proclaim: Pronounce 136 7.31 Proclaim: Endorse 114 6.13 DISCLAIM 842 45.27 Disclaim: Deny 376 20.22 Disclaim: Counter 466 25.05 CITED-EXPANSION Ex-expansion 12 0.65 Ex-contraction 48 2.58 CITED-CONTRACTION Co-expansion 10 0.54 Co-contraction 40 2.156.2 ENGAGEMENT IN THE ENGLISH AND SPANISH TEXTS

Table 3 shows the distribution of the Engagement expressions of the major categories in the English and Spanish texts (originals and translations). Although the distribution of the frequencies of the categories is similar at first sight, the chi-square test has proved that the difference is significant, thus partly disconfirming the first hypothesis. This difference is due to the higher number of Contraction expressions in the Spanish texts, and above all in the Citedexpansion fragments, which are more than twice as common in the English texts; that is, the translations have not always maintained the Appraisal categories of the original. An example is (27), which occurs within a quotation, where the translator includes an expression of Cited expansion: ex-Contraction that does not occur in the original (28).