Полная версия

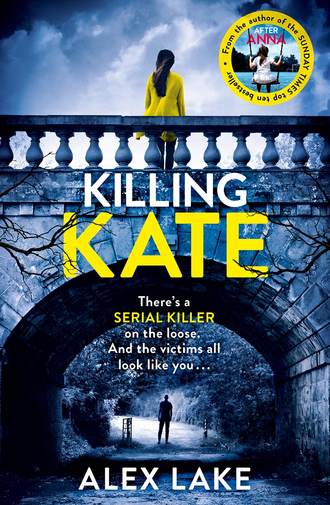

Killing Kate

Kate bridled at the suggestion that her home was so boring; she thought it could be quite lively, especially on a Friday night, but then he was older, and probably didn’t participate in the nightlife of the village to the degree that she did. Besides, before she’d left for Turkey there had been a big local story.

‘It wasn’t so sleepy last week,’ she said. ‘They found that body.’

It was the biggest news in the village Kate could remember. A woman her age had been killed only a few days before she left for Turkey. A dog walker – a magistrate out with his new puppy, Bella – had found a body stuffed into a hedge near the reservoir. It was a young girl, Jenna Taylor, in her late twenties. She’d been strangled, there was speculation that she had been raped, too, although the news reports had been vague, which only served to fuel rumours that something really sick had taken place.

‘I heard,’ Mike said. ‘I read about it online. I haven’t been following it, though. It happened about a week after I got here, and you know what it’s like on holiday. You tend to switch off. One of my friends has been keeping track of it. He said they still haven’t found whoever did it.’

‘I heard they arrested her boyfriend,’ Kate said. ‘One of my friends is addicted to reading about it, but she’s like that with every news event.’

‘Did you know the victim?’ Mike said. ‘She was about your age, wasn’t she?’

‘She was,’ Kate said. ‘But I didn’t know her. She moved from Liverpool a few years ago. We would have been at high school together though, if she was from Stockton Heath.’

What she didn’t say was what her friends had been teasing her about ever since: she and Jenna Taylor could have been sisters. They had the same long hair, lithe figure and dark eyes. It was no more than a coincidence, but still, she didn’t like it. It wasn’t the kind of coincidence that you found intriguing; it was the other kind, the kind that you found disturbing.

Mike shook his head. ‘Unbelievable,’ he said. ‘I go away for a few weeks and all hell breaks loose.’

Kate gave a half smile. She wasn’t listening any more. She’d had enough of making conversation. All she wanted was to go back to her hotel and her friends.

She finished the drink and put the cup on the counter. ‘Thanks,’ she said. ‘I have to get moving.’

There was a flicker of disappointment on Mike’s face. ‘You want to meet up later?’

Kate paused. For a second she felt almost obliged to say yes, but she caught herself. She didn’t have to be polite. She owed him nothing.

‘I don’t think so,’ she said. She searched for an excuse – what? A prior engagement? Didn’t want to leave her friends – but none came. ‘I don’t think so,’ she repeated, simply.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘I understand. From the look on your face, I’m guessing that you won’t want to meet up another night, either?’

She shook her head. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Sorry.’

She put her hand on the front door to open it.

‘You know your way home?’ Mike said. ‘Where are you staying?’

She didn’t want to give him the name of their hotel. ‘Near the harbour.’

‘Go out of the main door and turn right,’ he said. ‘It’s not far. I can call you a cab, though, if you’d like?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘No thanks. I’ll walk. I could do with the fresh air.’

‘All right,’ he said, with a rueful grin. ‘Maybe I’ll see you round and about in Stockton Heath.’

She hoped not. She really, really hoped not.

4

Phil Flanagan signed the change order on his desk. He’d barely read it; he was a project manager on a residential housing development, but given how he was feeling it was a struggle to muster up the enthusiasm to care about his job. It was a struggle to muster up the enthusiasm to care about anything.

Not with Kate gone. It was bad enough that she’d broken up with him, but now she was on holiday, living it up in the sun. Surrounded by men who would be ogling her by day and pawing her in the pubs and clubs by night. God, he couldn’t stand the thought of it. Couldn’t bear to picture it.

But he couldn’t stop himself. All day long images of her in bed with a faceless man, their naked, suntanned limbs passionately entwined, tortured him. Which was the reason he was barely paying lip service to his job.

He stared at his signature on the paper. He hated his name, hated the alliteration of Phil and Flanagan. He’d always had the idea that he was going to change it someday; originally he’d planned for that day to be the day he got married, when, in a grand romantic gesture that would both impress her and get rid of his horrible name, he would take her name. But that plan was out of the window now that she’d dumped him because she needed some fucking space, needed to see what life was like without him. Well, he could tell her what it was like, it was rubbish, totally fucking rubbish, just a series of minutes and hours and days all merging into one big morass of him missing her and wondering where she was and if she was in bed with some greasy fucking foreigner on holiday. And at the back of it all, the question: why, why had she done it?

And what was he supposed to do now? His whole life had been planned around her: get married in the next year or so, then kids, then grandkids, then retirement, then their last few years eating soup together in a home somewhere, before dying, her first, then him a few days later of a broken heart.

It wouldn’t say broken heart on the death certificate, but that was what it would be, and all the people in the nursing home would agree about it. They’d smile at each other and say how lovely it was – sad, but lovely – that he couldn’t live without his wife of seventy years.

Well, that wouldn’t happen now, and the loss of it stung.

He’d known there was something wrong a few weeks back, when he’d suggested that they get started on planning their wedding. They weren’t engaged, not yet. Not officially, at any rate. Not in the announced-to-the-world sense. That would come in due course, but he saw no reason not to start at least discussing the main points of their wedding-to-be – possible locations, numbers, all that stuff – because they were going to get married, of course they were. Everyone knew that. Everyone had known it for years.

Sure, she said. We should start thinking about it.

We should check out some venues. I was thinking Lowstone Hall, or maybe the Brunswick Hotel, if we wanted something more modern.

Yeah, maybe, she said. Let’s think about it.

So should I contact them? Do you like those places?

Er – let me think about it. I’m not sure.

Not sure? Phil said. We talked about both those places a while back. What changed?

She wouldn’t look him in the eye. Nothing. I just – let me think about it, OK?

He’d thought it was odd, that there was something different in her manner. But he had not been expecting what came a week after that.

Phil, she said. We need to talk about something.

And then she told him. Told him that they’d been together since they were teenagers and she wasn’t sure he was the right person for her any more. She wanted a break. Wanted some time apart so she could live her life, make sure she knew who she was, that she was not sleepwalking into a bad decision.

So it’s a break? He said. For how long?

Maybe a break, she said. Maybe not.

But if it is, how long for?

I don’t know, Phil. I can’t say.

He felt his world slipping through his fingertips. You don’t have to be exact, Kate. But what order of magnitude are we talking? A week? A month?

More, probably. Six months? I don’t know. She looked at him, tears in her eyes. I think it’ll be easier if we say it’s for good. That’ll stop you wondering.

No, he said. That’s not easier. Not at all. It’s a lot worse.

And that was how they’d left it. Him: broken, devastated, unsure of what to do from minute to minute, staying in his friend Andy’s scruffy flat. Her: on holiday in Turkey, living it up with her friends.

On his desk his phone began to vibrate. It was Michelle, a girl he’d met the weekend before. He’d called Kate from her house – from the bathroom – drunk as all get out, expecting her to be sad when she saw how easily he had moved on, to understand what she had lost and to say, Come over, Phil, leave her and come back to me.

It hadn’t quite ended like that.

To make matters worse, in the morning he’d sat there drinking tea on Michelle’s couch and all he could think was Shit, she looks like Kate, like a pale imitation of Kate. He hadn’t noticed it the night before. He hadn’t noticed much of anything with about six beers and a bunch of whisky and Coke swilling around in his belly.

And now she was calling him. He was going to tell her he couldn’t see her. He liked her – she was nice enough – but he knew that there was no future with her. It was rebound sex, a way to take his mind off what had happened, and, even if he’d wanted to do it again, he knew it wasn’t fair to use her like that. He picked up his phone.

‘Michelle,’ he said. ‘How are you?’

‘Good!’ She was, he remembered, from Blackpool, and the false brightness in her voice matched the false confidence of the fading seaside resort. ‘You?’

‘Fine, yeah.’

‘What are you doing tonight? Want to meet up?’ There was a nervous quiver in her voice.

He was about to say No, I can’t, and I’m not sure we should meet up again, it’s not you, it’s me, I recently came out of a difficult relationship … But then the image of an evening in Andy’s empty flat – Andy was away with work – drinking alone to quiet his thoughts, came to him, and he thought Why not? It’s only a drink. It doesn’t have to mean anything.

‘Sure,’ he said. ‘Sounds great. Where do you want to meet?’

‘The Mulberry Tree?’ she said. ‘Seven?’

Just after seven he walked into the Mulberry Tree. It was a popular pub in the centre of Stockton Heath. Michelle was sitting at a table, a half-drunk glass of white wine in front of her.

Phil gestured to the glass. ‘Another?’

Michelle nodded. ‘I got here a bit early,’ she said. ‘I came on the bus. It was either arrive ten minutes early or half an hour late.’

She didn’t drive. He remembered her telling him; she’d failed her test three times then given up trying.

‘I’ll be right back,’ he said.

As the barman poured the drinks he glanced at her. She was shorter than Kate, and had a rounder, chubbier face, but there was a definite similarity. Long, straight dark hair, dark eyes, a quiet, watchful expression.

Jesus. Hanging out with a Kate lookalike was hardly going to take his mind off his ex.

He paid and took the drinks to the table.

‘Here you go,’ he said, and raised his glass. ‘Cheers.’

Michelle clinked his glass. ‘You see the latest on the murder?’ she said. ‘I can’t believe it.’

Phil hadn’t. He was too wrapped up in his own misery to pay attention to other people’s.

‘What is it?’ he said. ‘I’ve not been following it. It’s only more darkness in the world.’

She looked at him with a teasing smile. ‘You’re a bundle of fun,’ she said. ‘Anyway, the cops arrested the boyfriend.’ She leaned forward, her tone conspiratorial. ‘It’s always the boyfriend, or the husband. She was probably sleeping with someone else, or something like that.’ She shook her head. ‘That kind of violence – it can only come from a strong emotion, you know?’

‘I guess,’ Phil said. ‘I wouldn’t really know.’

‘I’d hope not!’ Michelle said. She leaned back. ‘Anyway, enough of that. How’ve you been?’

‘Fine,’ he said. ‘Fine.’

‘That’s it?’ Michelle said. ‘Just fine?’

He stared at her, a feeling of hopelessness washing over him. He could hardly tell her the truth, could hardly confess that he was unable to sleep, his nights filled with obsessive thoughts of his ex, an ex who looked like the woman he was currently out on a date with, a fact which only made matters worse. Could hardly tell her that he didn’t want to be here, that he was only here because he had to do something, had to find a way to take his mind off Kate, and he had hoped that this might do that, at least a little bit.

Could hardly tell her that it wasn’t working, and all he wanted to do was leave.

‘Been a tough day at work,’ he said.

‘What do you do?’ Michelle said.

Jesus, she didn’t even know what he did for a job. He wasn’t ready for this, wasn’t ready to make a new start with someone. He was suddenly overwhelmingly tired.

‘I have to go,’ he said. ‘I don’t feel well.’

She frowned. ‘I just got here! It took two buses!’

‘I’m sorry. It’s not your fault. I’ve been fighting something all day – flu, I think, it’s been going round the office – and it just hit me. I should have cancelled.’ He took a twenty-pound note from his wallet and put it on the table. ‘Take a taxi home. On me. Sorry, Michelle.’

‘I don’t want money!’

Phil ignored her. He got to his feet, his head spinning. He felt faint, nauseous now.

‘Are you OK?’ Michelle said, her tone switching from anger to concern. ‘You do look a bit poorly.’

He waved a hand. ‘I’ll be all right,’ he muttered, and fled.

5

When Kate got back to the hotel room May and Gemma were still sleeping. There were two double beds in the room; Kate and May were sharing one, leaving the other to Gemma. It wasn’t a generous gesture; they knew from long experience that Gemma was a very active sleeper who would stealthily colonize your side of the bed, gradually creeping closer and closer to you until she was pushing you over the edge. If you got out and switched sides, she would start to move towards you again; you’d hear her coming and the stress of it would keep you from falling asleep. Allied to the fact that she was a very deep sleeper, who was near impossible to wake up, and she was not anybody’s preferred sleeping partner.

Her boyfriend – a maths teacher called Matt – claimed that he had to decamp to the couch five nights a week in order to get some sleep. He had, he said, been collecting data on his sleeping arrangements and was using it to teach statistics to his students. He showed it to Kate once: he’d plotted a bell curve, showing that five nights per week was the mean average, with a standard deviation of three sigma. Kate had no idea what that meant in statistical terms, but she was pretty sure that in the real world it meant that he was not getting enough sleep and was in danger of becoming obsessed with it.

Kate opened the bathroom door and turned on the shower. She stripped off and climbed under the hot water, letting it first soothe and then invigorate her. The shower shelf was crammed with bottles of shampoo and conditioner and she grabbed hers, a tea-tree oil shampoo from Australia. A large part of her was sceptical about the value of these toiletries; Phil always said that they were all just soap anyway so she may as well buy the Tesco value pack for a few pounds, rather than spend a small fortune on the designer stuff. She suspected he had a point, but it wasn’t about the chemistry of whatever was in the bottles. It was about the routine, the feeling that she was, in some way, pampering herself, treating herself to something special.

She stepped out of the shower and wrapped herself in a towel. It was a plush, white Egyptian cotton towel and it felt luxurious against her skin. It was these little things that made staying in a hotel so amazing: clean, soft towels every day, a freshly made bed, coffee and breakfast at the end of a phone line.

She went into the bedroom. May and Gemma were still sleeping. May’s side of the room was tidy, the carpet empty apart from a small pile of neatly folded clothes from the night before. Her other clothes were either hanging up in the wardrobe or carefully arranged in a drawer. Gemma’s side, on the other hand, was a total mess: inside-out jeans hanging off a chair, bras and underwear littering the floor, one of a pair of flats on the pillow next to her head.

It had always been this way: Gemma and May were total opposites. May: organized, precise, together, always on time, following the plan. Gemma: unaware there was a plan, haphazard, confused, totally oblivious that she was supposed to arrive at whatever place she was going to at any particular time.

But they, along with Kate, had been friends forever. Since the day they met as five-year-olds at St Stephen’s Primary they had been a unit. They’d been friends for over twenty years: they’d grown up together, seen each other’s characters develop and emerge. They knew each other as well as they knew themselves, understood how and why they had become the people they were, and they loved each other in a deep and profound way.

Kate opened the minibar and took out a small, over-priced, glass bottle of orange juice. Normally she wouldn’t have spent three pounds fifty – she did the maths to convert the currency in her head – on what was little more than a tiny sip of juice, but she was suddenly overwhelmed by the desire for something sweet. That, she thought, was the price you paid for a hangover, and the reason they had these ludicrously expensive minibars in the first place.

Behind her, May stirred. Her eyes opened and she looked hazily at Kate while she emerged fully from unconsciousness.

‘Splashing out?’ she said.

‘Thirsty,’ Kate replied. ‘I needed something sweet.’

‘Me too.’ May held out a hand. ‘Can I have some?’

‘There’s not much.’

‘Just a sip. I’m feeling a bit delicate.’

Kate swallowed half the contents and handed the bottle to her friend. ‘Finish it.’

‘So,’ May said. ‘You arranged your own accommodation last night?’

‘I suppose so,’ Kate said. ‘I wasn’t sure where I was this morning.’

‘Did you guys – you know?’

‘No.’ Kate shook her head. ‘I tried to, but he told me I was too drunk.’

‘Nice guy. Most would have taken advantage.’

‘I guess.’ Kate paused. ‘But nothing about last night feels good. What I remember of it, that is.’

‘It’s not like you.’

‘I know. I feel awful. I can’t believe it. I had way too much to drink. Don’t let me do that again.’

‘We would have stopped you, but you disappeared with that guy.’ She sipped the orange juice. ‘We were worried, Kate, in case he turned out to be some crazy weirdo, but then you texted to say you were OK, so we left you to it.’

‘He was fine. He didn’t do anything, thank God. In fact, it was me who suggested we have sex.’ She shook her head. ‘I can’t quite believe it.’

‘Are you going to see him again?’

‘No,’ Kate said. ‘He wanted to, but I can’t face it. He was nice enough, but I’d rather forget it happened.’

‘We’ll have to avoid that club, then. In case he’s in there. And if we’re in other places I suppose we’ll have to keep an eye out for him.’

Kate raised an eyebrow. ‘That’s not the only place we’ll have to keep an eye out for him. Guess where he lives.’

‘Where?’

‘Guess.’

May shrugged. ‘London?’

‘No. Guess again.’

‘Manchester?’

‘Warmer.’

May raised her eyebrows. ‘Somewhere close to us?’

‘Very close.’ Kate sat on the end of the bed. ‘He lives in none other than Moore.’

May leaned forwards, propping herself up on her elbows. ‘You mean Moore? The Moore down the road?’

‘The same.’

‘You are fucking kidding me.’

‘I wish I was.’

‘You’re saying he’s from the same pokey part of the world as us? Did you know him?’

Kate shook her head. ‘No, although he did seem familiar once I knew. I suppose I might have seen him around. He’s older, though, so he wouldn’t necessarily hang out in the places we do.’

‘How much older?’

‘Late thirties. Something like that. I didn’t ask.’

‘Got yourself a sugar daddy,’ May said. ‘Lucky you.’

‘Don’t even joke about it,’ Kate replied. ‘This is not funny. Maybe I’ll be able to laugh about it later, but not now.’

‘What’s he doing here?’

‘Holiday. He’s been here a couple of weeks already, hanging out with some friends.’

‘And you’re not going to see him again?’

‘No,’ Kate said. ‘Definitely not.’

The hotel phone started to ring. May looked up at Kate. ‘Do you think that’s him?’ she said.

‘I hope not,’ Kate replied. ‘I didn’t give him the name of the hotel. Shit, I hope he didn’t follow me here.’

‘I’ll get it,’ May said. ‘If it’s him, I’ll tell him I don’t know you and he’s got the wrong number. OK?’

Kate nodded. ‘OK.’

May reached out and picked up the phone.

‘Hello?’ she said. There was a long pause, then she held out the receiver to Kate. ‘It’s for you,’ she said.

‘Is it him?’

‘No,’ May said, and rolled her eyes. ‘It’s Phil.’

6

Kate took the receiver from May and put it to her ear.

‘Phil?’ she said. ‘What are you doing? Is something wrong?’

His voice was tense, a note or two higher than usual. ‘I wanted to talk to you. You haven’t been answering your phone. I thought maybe you don’t have reception.’

‘It’s pretty patchy,’ she lied. ‘I saw some missed calls’ – some, she thought, didn’t cover it. There’d been dozens of them – ‘but I haven’t been able to call back.’

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘I understand.’

‘So,’ Kate said. ‘Is something wrong?’

‘No. I just – I just wanted to talk to you. Check you’re OK.’

‘I’m fine,’ Kate said, her mouth tightening. ‘I’m a big girl, Phil. I can look after myself.’

‘I know, but—’

‘And how did you get this number?’ Kate said.

‘I asked your mum and dad where you’re staying.’

The answer was too quick; she knew Phil and she could tell it was a lie he’d prepared earlier. She wasn’t even sure she’d told her parents where she was staying. It pissed her off; this whole phone call pissed her off. She decided not to let him off the hook.

‘Are you sure?’ she said. ‘I don’t recall telling them the hotel name. In fact, I’m pretty sure I didn’t, now I think about it. So how did you get the number?’

He paused. ‘I called around,’ he said finally.

‘Called around what?’

‘The hotels.’

Kate stared at her reflection in the mirror opposite the bed. ‘You called every hotel in the resort?’

‘No!’ he said, a hint of outrage in his voice that she would suggest he was that desperate. ‘I knew you were staying near the harbour, so I called those hotels and asked to be put through to your room.’

‘Right,’ Kate said. ‘So you called every hotel near the harbour.’ She shook her head, exasperated. Why couldn’t he leave her alone, even for one week? One week, so she could enjoy her holiday.

‘Well, it’s nice to talk, but I’m kind of busy right now,’ Kate said. ‘We’re getting ready to go out for breakfast.’ She looked at Gemma, spread out in a star shape, her cheek pressed against the pillow, her mouth half-open as she snored lightly. ‘May and Gem are by the door.’

May suppressed a snort of laughter. Kate glared at her.

‘I only wanted to chat. I miss you.’

‘Can we talk later?’ she said. ‘I’ve got to go. They’re waiting. And we’re hungry.’

‘Will you call later?’ he said.

‘Sure.’

‘You promise you’ll call?’

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘I promise.’ It was a promise she felt she would be justified in forgiving herself for breaking.

As she put the phone in its cradle, Gemma’s eyes opened.

‘Who was that?’ she said, her voice little more than a croak.