Полная версия

When Sophie Met Darcy Day

While Lucy was there, we had a visit one day from a racehorse owner driving a Mercedes, who’d come to check us out and decide if we were the best home for one of his retired horses. I think the stables were a lot more dilapidated than he was used to, but when he saw the condition of our animals, he agreed that his horse, Freddy, could come to us. He duly arrived the next day in a smart trailer. Freddy was a smallish bay with a white blaze down his nose and he was in peak condition, having only come out of training a few weeks before. He danced about as he was unloaded, putting flight to the hens and some geese.

Freddy had had an ignominious end to his ten-year racing career, going from being the winner of Group 1 races at the age of two to trailing at the back of the field more recently. It would take a degree of expertise to retrain him for another career, but I thought we had a good chance of managing it. I stood him in a stable for a day or so to get used to us, then Lucy was with me when I led him up to the field at the end of the lane where we kept our other geldings. Freddy was as naughty as a two-year-old colt, rearing up on his hind legs as I led him, and I thought, ‘Uh-oh, we’re going to have our work cut out.’ He was obviously a highly strung creature.

As soon as I released him into the field, he galloped straight up to the other horses and tried to push his way into the middle of the herd. He obviously didn’t know that there was a pecking order in a herd and new members have to approach slowly and show respect. One horse nosed him roughly out of the way, then another did the same.

‘What are they doing?’ Lucy cried, and I realised she had tears in her eyes. ‘They’re going to hurt him.’

‘No, they won’t,’ I said, watching carefully just in case I was wrong. Freddy approached the group again, but they wouldn’t let him near, rejecting his advances until eventually, head down, he wandered off to graze on his own in a corner.

‘Why won’t they be friends with him?’ Lucy asked, her voice cracking.

Suddenly I realised this was touching a raw nerve for her and I chose my words carefully. ‘Freddy’s been used to being on his own a lot, or with his trainer and jockey, and he’s forgotten how to get on with other horses. He has to earn his place in the herd and wait for them to invite him in instead of charging full pelt into the middle and demanding attention. But don’t worry. It will work itself out eventually.’

‘He must be really upset about it.’

‘Yes, he probably is. But it will be all right in the end.’ At least I hoped it would.

We had to supplement Freddy’s diet while he adjusted to grazing, having previously been fed on concentrates. It became Lucy’s job to go up to the field twice a day and feed him from a bucket, trying to keep it hidden from the rest of the herd so they didn’t think he was getting special treatment, which would have made things much harder. As Lucy fed him, she would stroke his nose and whisper to him, and it was obvious that this lonely girl felt a great affinity for the lonely horse.

From time to time, if another horse was standing separately from the rest of the herd, Freddy would try another approach, sauntering up hopefully, but he was usually met with a hostile kick or a push. He’d panic then canter away again to his solitary grazing. After a few days of this, he started to get nervous when other horses came near and I was concerned that the situation wasn’t resolving itself as quickly as I’d hoped. Fear is always alienating. If a child is scared of dogs and starts behaving oddly around them, even the friendliest breeds of dog will respond by barking or jumping up and will scare the child even more. However, if a child can stay calm, the dogs will be calm too, and it’s the same with horses. Freddy would have to learn to calm down, and this would take time.

‘Why don’t they understand that he only wants to make friends?’ Lucy asked me over and over again.

‘He’s already got a friend,’ I told her. ‘Have you noticed how much he brightens up when you come along?’ It was true. Freddy always rushed over as soon as he saw Lucy approaching the field, whether she was carrying a feed bucket or not. One day, I saw the two of them lying on the grass beside each other, with Lucy chatting quietly and Freddy still and listening. I would have loved to have eavesdropped but if they’d noticed me, it would have spoiled the moment.

‘Freddy was lying down in the field today,’ Lucy told me later, and I knew that was a good sign, because it meant he was settling and wasn’t so scared of the others.

Not long after that, there were a few telltale signs that Freddy was being accepted by the herd. It started with some sniffing of noses, and then a little grooming of necks. Freddy let the others make the approach without either running away or responding with too much eagerness, and in return it seemed they were beginning to accept him.

Around this time, I watched Lucy trying to catch Flirty Gertie one morning, trying hard not to laugh as she kept slipping out of reach. Finally I stepped in to help. I talked to Gertie quietly, approaching very gradually then stooping down using slow, careful movements, and she let me pick her up.

‘Do you see how I did that?’ I asked. ‘You can’t force your presence on a hen, especially not one like Gertie. You need to gain her trust first of all.’

‘OK,’ Lucy nodded, and over the next few days I watched her get the hang of it. She was getting on better with the dogs as well, and one lunchtime I eavesdropped while Sandy was telling her about a new CD she’d bought and Lucy didn’t interrupt once to boast that she had better CDs at home. She was learning.

I’d like to say Lucy became friends with the other children at Greatwood that summer, but nothing happens that quickly after a bad first impression has been formed. However, she made a firm friend of Freddy. After the two weeks she stayed with us, Lucy kept popping back to see Freddy whenever she could, and as soon as he spotted her coming down the lane, Freddy would rush up to the fence to greet her. There was a meeting of kindred spirits there that I think helped both of them through a difficult time.

The summer holidays ended and Lucy went back to school, so she could only visit us at weekends. Her father phoned us one evening, though.

‘I can’t thank you enough for what you did for Lucy over the summer,’ he said. ‘She seems much more settled at school and has made some new friends, so we’re very grateful.’

‘So are we,’ I said. ‘She helped us to settle a highly temperamental racehorse who needed the kind of one-toone attention I didn’t have time to give it. Your daughter is good with horses. She has a knack.’

A few months later, Lucy’s family moved overseas and we lost touch. Still, we felt something rather wonderful had happened. We were feeling particularly pleased with ourselves when we got a sharp reminder not to take anything for granted – the bank foreclosed our account. We couldn’t take out cash or write cheques for anything any more. In order to keep going, we had to sit down and apply for as many credit cards as we could, with the maximum credit limit they would give us. From now on we would be living off the never-never.

Chapter 5

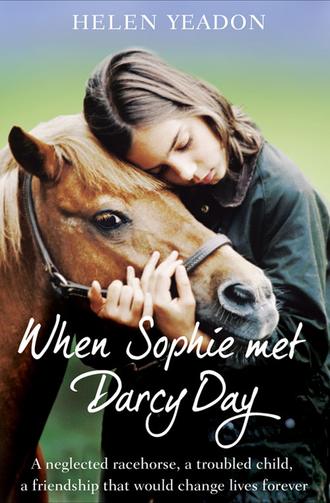

Sophie and Darcy Day

A car pulling a trailer came up the drive and stopped in the yard one morning in late summer. Usually horses start stamping when their trailer comes to a standstill but there was no sound from this one and I worried that its occupant might have got injured on the journey, and might even be down, although I would have thought that the driver would have heard if anything untoward had happened.

Michael let the tailgate down and a desperate sight met my eyes. Darcy was bony, her head hanging low over the bars, and her coat was matted and discoloured. Over the years, I’d seen many horses in poor condition but this one rocked me on my heels. I climbed into the trailer to untie her, talking in a soft, low voice, but she didn’t even raise her head to look at me. This was an animal who had given up on the world.

The woman driver introduced herself and told us that she had rescued Darcy from a place where she was being severely neglected but that she couldn’t afford to keep her herself. Would we be able to help? Of course we would. There was no question. I was just concerned about how I was going to get her to back down the ramp out of the trailer because she was in such weak condition she could have collapsed at any time.

Gently, step by faltering step, Michael guided her down while I helped at the other end, until she stood trembling in the yard in front of us. She was a mess. Her eyes were dull and streaming, her bones protruding through her coat, her hind legs swollen and oozing a yellow discharge, her tail a tangled mass of wet hair and diarrhoea, her hooves long and overgrown. Her temperature was sky high and I knew she needed intravenous medication quickly. I went indoors to ring Adrian, the local vet, while Michael led Darcy slowly to the old sheep barn where she could be nursed in peace. We had a nursery paddock in front of the house where we sometimes put poorly horses because we could listen out for them in the night, but it was clear that Darcy was nowhere near well enough to be outside.

When Adrian arrived, he whistled through his teeth. The strain of the journey had obviously taken its toll on Darcy. She was clearly very distressed and had broken out in a heavy sweat. Her temperature remained way above normal, her hind legs were hot and swollen and the skin had split in several places.

‘It’s a nasty case of lymphangitis,’ Adrian said, ‘started from infected cuts on her legs.’ He injected her with a hefty dose of painkillers, as well as antibiotics and anti-inflammatories to kick-start the healing process.

Michael brought out some buckets of warm water and Adrian cleaned Darcy’s hind legs as best he could, then bandaged them. He bathed her eyes and put in some eyedrops. The only good news to emerge from his head-to-hoof medical check was that she didn’t have lice, which would have meant that we would have been forced to keep her in isolation.

‘She may develop colic,’ Adrian said. ‘I can’t tell yet. You’ll have to keep a close eye on her temperature and watch her like a hawk for the next few days to see if she turns the corner.’

The word ‘if’ hung in the air. What he was saying was that there was a good chance she wouldn’t. This horse seemed to have lost the will to live.

‘She needs company,’ I said to Michael. ‘Maybe if we bring in another horse and they get along together, she’ll perk up a bit.’

He agreed – but which one should it be?

‘Tish!’ we both said together.

Tish was a little Shetland pony, only 28 inches tall, who had come to us after a horrific incident in which several men had attacked him with shovels and beaten him badly, all because he bit a child who was petting him at a show. Who knows what that child was actually doing to him at the time? Those men didn’t wait to hear if there had been any provocation before laying into him. Once he arrived at Greatwood and recovered from his beating, we found Tish to be a cheeky, cheerful, entertaining character with a strong personality, who wouldn’t let any of the much bigger horses take advantage. He’d be the ideal equine companion for Darcy: too small to appear a threat, but perky enough to attract her attention.

I went out to the field to try to catch Tish – no mean feat when he doesn’t want to be caught – and finally managed to lead him to the sheep barn where Darcy was standing alone in the corner. Tish marched straight in and helped himself to a huge mouthful of the fresh meadow hay we had left for Darcy. Darcy looked up, surprised, then edged over to sniff Tish’s bottom. Tish gave a swift warning kick with one of his back feet and carried on munching. Darcy went over to stand beside him, avoiding the back legs, looked cautiously out of the corner of her eye, and then bent down and picked up a wisp of hay in her mouth. They stood side by side eating from the same pile, which meant they were accepting each other. It was a huge step forwards for Darcy.

For the rest of the day Tish and Darcy ignored each other but at the same time continued to be quite happy in each other’s company, so we felt confident enough to leave them overnight in the same barn. Next morning, I hurried outside as soon as I awoke to find Darcy’s temperature had gone down. Her eyes were brightening and she was obviously feeling a lot better, although she still paid no attention to Michael or me. She accepted everything we did for her with a resigned air but without any responsiveness or gratitude.

We had to walk her a few times a day to help the swelling in her legs, and when we led her out of the barn, Tish would call out for her and she would whinny in reply. A relationship was forming. Within three days, they were inseparable and when we wanted to take Darcy out for a walk, Tish had to be taken along as well. Darcy had made a friend.

A few days after Darcy’s arrival, a car pulled into the yard and a woman wound down the window to talk to Michael.

‘We heard that you have children here to help on Saturday mornings and we wondered if you would have our daughter Sophie?’

He glanced into the back seat and saw a dark-haired girl staring at her lap. ‘OK,’ he said. ‘That’s fine.’

The woman started talking, and it was as if the flood-gates opened. ‘Her father and I are very worried. You see, she’s stopped talking – she hasn’t spoken a word for two years. We don’t know what to do but she likes reading books about horses and we heard about you and thought maybe …’

‘That’s fine,’ Michael said again, curious now about this girl who seemingly didn’t talk.

‘We’ll be back in a couple of hours,’ the mother said. ‘We don’t want her to be a burden to you. We’ll just do a bit of shopping and come back. She’s got a mobile phone in her pocket with our number on it and if she rings, we’ll come straight away.’

The car door opened and Sophie stepped out, a sullen look on her face. She was overweight and had made no effort with her appearance, with her baggy, ill-fitting clothes and her lanky, unwashed hair. But more than that, it was her general demeanour that told me she was depressed. She was hunched, as though there were a heavy weight pressing down on her, and she could barely find the energy to lift one foot after the other and walk.

As her parents drove off, I swept over and introduced myself. ‘I’m just on the way to change the dressings on a horse called Darcy,’ I told her. ‘Come with me.’ On the way to the barn, I explained about the condition Darcy had arrived in just a few days earlier and what steps we were taking to try to help her. There was no reaction and I began to wonder if Sophie had a hearing as well as a speech problem.

And then the three of us – Michael, Sophie and me – walked into the barn, and Darcy astonished us by going straight over to Sophie and lowering her head to be petted.

‘I brought her a great big breakfast this morning and she never comes over to me,’ I complained, but really I didn’t mind at all. We never ask for anything in return from horses we rescue. That’s not how it works.

I could tell Sophie was pleased. She held out her hands and Darcy put her nose into them. Even though she must still have been feeling rotten with her legs and all her other health complaints, she was able to make a connection with this silent little child.

I laid out the equipment for changing the dressings and as I worked, I asked Sophie to hand me the items I needed. She seemed bright enough, finding the correct bandages or tubes of ointment and holding them out until I was ready to take them, but it felt strange talking to someone who never talked back. Michael and I found ourselves chatting more than we normally would have just to fill the silence.

After I’d finished with Darcy, I led Sophie to the hen house and showed her how to look for eggs, and how to feed the chickens, then she just trailed round helping me with my normal jobs for the next couple of hours until her parents came back. I decided not to introduce her to the rest of the children in the stable, because they wouldn’t have been able to resist asking questions and possibly even making fun of her. It seemed better to keep her busy and out of the way of the others.

When Sophie saw her parents’ car, she walked across to it with the same sullen posture as when she’d arrived, opened the back door and climbed in. She didn’t so much as wave goodbye to us.

‘Thank you very much,’ her mother shouted out of the window as they left.

‘Do you think she’ll be back next week?’ I asked Michael.

‘I don’t know.’

‘She seems very troubled. I wonder what that could be about?’

‘Who knows? Perhaps she’s perfectly capable of speaking and has just decided to rebel, but you’d think the odd word would have slipped out at some stage over the last two years.’ Michael rubbed his chin thoughtfully.

‘I was wondering if she’s had some kind of traumatic experience. Maybe she’s being bullied at school.’

I’d been bullied myself, back at the age of thirteen. We’d left the farm where I’d had such a happy childhood with my horses, and moved to a town. At the new school I was sent to, the other girls found me very unstreetwise. They were interested in boys and dating, while all I cared about was animals. On the first day, one girl ran a finger down my back to see if I was wearing a bra, and they all laughed when they found I wasn’t. They weren’t violent towards me but they treated me as though I were some lowly creature, not worthy of attention, so I’ve always felt sympathetic to any children in the same situation.

During the following week, my thoughts kept returning to Sophie and I wondered whether I should have handled her differently, but I decided that my policy of just treating her as if everything were completely normal was the best one. She didn’t want me bombarding her with questions and I’m sure she’d had enough people coaxing and cajoling her to speak both at home and at school. It seemed most natural to me to pretend everything was fine, that her silence was nothing out of the ordinary.

The following Saturday, I was surprised but pleased when I saw her parents’ car pulling into the yard and watched Sophie climbing out of the back door.

‘Is it all right if she stays another couple of hours with you this morning?’ her mother called.

‘Yes, of course,’ I replied. ‘Sophie, do you want to come and see Darcy? Her legs are much better than they were last week.’

She followed me eagerly, and once again Darcy came over to see her as soon as we entered the barn, making a gentle whickering sound. She definitely recognised Sophie, because she didn’t get up and come over to any of the other children. I told Sophie this and she looked very pleased.

‘Why don’t I teach you how to groom her?’ I suggested. ‘These are the brushes here.’ I showed her how to stand round the back of the horse and start by feeling it all over with your hands, smoothing down in the direction of the hair, watching the horse’s reaction to your touch, before you start work with a brush. I told her that the tummy can be tickly so you’ve got to apply the right amount of pressure, and cautioned her to avoid Darcy’s injured legs.

Sophie started work with enthusiasm, concentrating hard on doing the job to the best of her ability. Darcy was enjoying it so much that her eyelids began to droop and she almost nodded off on her feet. That’s a huge compliment from a horse, implying absolute trust, and it was yet another sign of the growing bond between them.

I took the opportunity to go and have a chat with the other children who were there that day. I explained to them about Sophie not talking and asked them just to treat her normally and not to refer to it. Bless them, they were as good as gold, accepting her as one of the crowd and ignoring the fact that she never joined in their conversations.

At the end of the morning, when the work was finished and the kids were waiting for their parents to pick them up, I usually invited them into the kitchen for a drink. I remember thinking on that second Saturday that Sophie seemed much more animated than before. Her eyes were sparkling, and when I asked if she would like a Coke, she nodded and smiled her thanks at me.

‘She seems happy enough here,’ Michael commented later. ‘I hope it does her some good.’

It felt odd at first that you talked to someone and there was no response, but we soon got used to it and hardly gave it a second thought. Sophie got into a routine of coming every Saturday and as soon as she got out of the car, she’d run to Darcy’s stable to see her. She slipped into the rhythm of the work on the farm, did as she was told, laughed and smiled with the other children, and seemed the same as them – until you stopped and realised that she was just listening rather than joining in their conversations.

Meanwhile, Darcy continued to recover. Her legs healed, her coat improved and she started to take an interest in life. Every Saturday Sophie would groom her until she was gleaming, and when I took her out for a walk around the yard, Sophie would come along, walking proudly by her side. She obviously felt possessive because whenever she could, she would slip into Darcy’s stable and sit on a bank of straw, just watching. Tish would stride around grumpily and I often heard her laughing at him. It was a pretty laugh, and it made me curious to hear her speaking voice.

There were a couple of occasions when I could feel that Sophie wanted to say something to me. Once I dropped Darcy’s bundle of hay on one side of the barn and Sophie made a noise that sounded like mild protest.

‘What is it?’ I asked.

She looked at me for a moment then rose, picked up the hay and moved it to the other side, and I remembered that that was where Darcy seemed to prefer it. It’s hard to remember every single horse’s individual preferences when you are feeding twenty of them every day, but Sophie knew exactly what Darcy liked.

‘I think she wants to talk,’ I told Michael later, ‘but I’m not sure if she can. Maybe there’s a physical problem?’

‘Her parents told me they’d explored every avenue,’ he said, ‘and I’m sure that’s true. I can sympathise with her, but I can also imagine her parents’ frustration as the weeks and months went by without her saying a word. They must want to grab her and shout “For goodness’ sake, will you just speak?”’

On a few other occasions, I heard Sophie make sounds that were like speech when she wanted to tell me something about Darcy, but they never came out as fully formed words. We got used to her muteness. It’s just the way she was. We were delighted to see her looking happier and more relaxed than when she first came to us, and we didn’t ask for anything more. When her parents’ car drew into the yard, she’d leap out, wave gaily at us and rush straight to Darcy’s barn to say hello. She’d smile and laugh, and enter into any fun going on in the yard, such as when the kids were splashing each other with water. She was a changed girl in many ways.

Towards the end of the summer, the volunteers were in the kitchen having their drinks while waiting for their parents. Michael and I were having a cup of tea and chatting to each other. Sophie was just round the corner from where we were standing. Suddenly Michael put his finger to his lips, then pointed to his ear, indicating that I should listen to something.

A girl’s voice was speaking. ‘I was just walking across the yard,’ it said, ‘which is a long way from the stable, but Darcy knew straight away I was there and she started to whinny. She always knows when I’m coming.’

I frowned and mouthed the word ‘Sophie?’ to Michael, and he nodded. We were both amazed. Her voice was childish-sounding but perfectly clear. I couldn’t work out who she was speaking to, so I wandered out casually, picking up an empty glass from the table, and glanced round at her to see she had her mobile phone to her ear.

I walked back to Michael and whispered, ‘She’s phoning someone.’