Полная версия

When Sophie Met Darcy Day

In the meantime, we had four mares that were all due to foal around the same time, and umpteen ewes that were due to lamb, which meant a couple of months at least when Michael and I would have to survive on very little sleep. Fortunately we have entirely different sleep patterns. I rise early and go to bed early, while he’s the opposite, so we agreed that he would sit up with them until 2am then I’d take over from 2 until morning.

Sometimes foaling was reasonably straightforward, but when it came to Chic we were in for a marathon. She was in labour for hours, the foal wasn’t in the correct position and we had to call the vet to come and turn it. Out it came, tiny and weak, but Chic was still in labour and we realised she had a twin in there, which was eventually born dead, about the size of a cat. The first foal was very weak and didn’t have a sucking reflex so we had to tube-feed him. He was shivering with cold, so I got one of my jumpers and threaded his tiny front legs through the sleeves, then I wrapped tinfoil round his back legs to try to retain the heat. He was a poor little creature. Chic licked him gently, every ounce the loving mother.

For three days we nursed that foal day and night, and on the third day we were heartened when he managed to get to his feet and stagger a few steps on what were impossibly long legs for such a tiny chap. Chic stayed very close, watching what we were doing and letting us milk her, but she didn’t try to intervene. She knew we were doing our best. Then on the fourth day, the foal’s breathing became laboured. I sat down beside him, put his head on my lap and whispered to him gently as he passed away in my arms. There was a huge lump in my throat. He’d struggled valiantly but was just too weak to live.

I felt so sorry for Chic. She’d been good and patient, and we’d all tried our hardest, but it wasn’t to be. She kept nudging the foal’s body, trying to get it to move, so we left her with it for a few hours so she could understand he had gone.

It would have been a crying shame if no good had come out of the experience so we asked around and found out about a local foal that had lost its mother, and we took Chic over to see if she would adopt it. We used that classic country trick of skinning Chic’s dead foal and placing the skin over the live one so that Chic would believe it was her own. Chic took to the new foal with alacrity, proving to be a most diligent mother, but Michael and I were pretty sure she wasn’t fooled. She knew her foal was dead and that this was a new one, but she made the decision to adopt it anyway.

No sooner was this drama over than the sheep started lambing and we had to sit up all night long to make sure the lambs emerged safely and weren’t then attacked by rats. It brought back many memories for me of watching my father presiding over lambing at the farm where I grew up. Once when I was just three years old, I watched him pulling out a lamb that wasn’t moving and he smacked it hard several times until it began to bleat. It obviously made an impression on me because at dinner that night, I told my mum: ‘That was a naughty lamb that crawled into its mummy’s bottom and Daddy did smack it hard.’

As soon as the lambs were big enough, we sold them, along with the rest of the flock (bar two), and, unlike the horses, I was glad to see the back of them. Sheep are a law unto themselves, with very few brain cells to rub together. Give me horses every time!

All the time we were firming up and clarifying the plans for our charity. There were already organisations out there dealing with poorly treated welfare horses. We wanted to focus on horses that were retired from racing while fit in body and mind, horses that we could retrain and pass on to good homes. The charity would retain ownership of each horse so we could check up on them and bring them back if the new owners were no longer able to keep them. We chose some trustees – Father Jeremy, the vicar at St Michael’s church just four miles away from Greatwood, and Alison Cocks, the woman whose orphan foal had been adopted by Chic. She had a profound knowledge of racing and horses, and we sang from the same hymn sheet when it came to horse welfare.

Next, we had a visit from two charity commissioners – men in suits who delicately picked their way over our cobblestones trying not to get anything nasty on their highly polished leather shoes. They interviewed Michael and me at length, being particularly concerned to establish that we were in it for the long haul. We knew this was serious. The charity would have to be run properly, with full annual accounts, and we would be guardians to all of the horses that passed through our care. When the commissioners finally left, they gave us no clue either way as to whether our application would be successful.

It was several months later, in August 1998, that we finally received a letter saying that we were now a registered charity, and giving us our charity number. It was just over three years since our move to Greatwood and it seemed somehow fitting that we should name the charity after this farm, where our work with ex-racehorses really started, and where we had already achieved some notable successes.

Vivien came to help us design all the forms we would need, such as the gifting forms that would have to be filled in by anyone who sent us a horse. This was designed to avoid a scam whereby someone could bring us a horse in very poor condition, let us pay all the vet’s bills and nurse it back to health, then return to claim it back again. With our contracts, we took on a duty of care for life, and even after we rehomed a horse we had the right to check up on it at any time to inspect its living conditions and general health. If a home check didn’t come up to scratch, we’d take the horse back again. It was our responsibility.

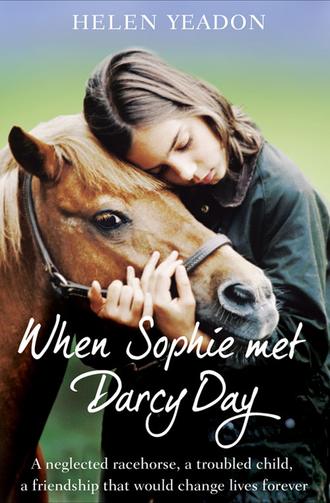

We wanted a Greatwood logo and were delighted when a funding trust gave us a grant that allowed us to employ a marketing company to design one for us. They came up with all sorts of ideas before a chance photograph taken by a local reporter provided the inspiration. A girl called Jodie had come to us for work experience and the photo caught her in silhouette as she looked up at a Thoroughbred. The image seemed perfect and worked well for the farm sign, letterheads and business cards. Little did we suspect at the time how relevant the juxta-position of a horse and a young person would turn out to be.

Soon horses started arriving thick and fast. Sometimes the RSPCA or another official charity asked us to step in, but on other occasions individuals just arrived on our doorstep with a horse in their trailer. Once we were brought nine horses in one delivery, all of them collected from an owner who hadn’t been taking proper care of them. We had to divide up our barns with partitions to keep the mares separate from the geldings, and our workload increased all the time.

It was a life I loved, but some family members found it difficult to comprehend. My father had only recently retired from a career as a very successful farmer and he thought we were mad. ‘You’ll never get rich like that,’ was his attitude. ‘So why give yourself all that work?’

On one visit he watched me nuzzling the horses as I walked through the stable and looked thoughtful.

‘Did I ever tell you that your grandfather used to train horses for the army during the First World War?’

I vaguely remembered hearing about this, and asked for more details.

‘He was awarded a medal for bravery. Once a cart carrying munitions was hit and your grandfather wriggled out to unharness the horses pulling it, despite the fact that he was under fire.’ Dad nodded. ‘I suppose your love of horses might have come from him. That might explain it.’

I liked that thought, but in fact I think it was all the horses I grew up around that gave me love and respect for these intelligent, sensitive creatures that all have unique personalities. I learned to ride when I was four, on a pony called Tam O’Shanter, but the horse I was most in love with as a child was called Shadow. She was an exracehorse, very feisty and wilful, but such a gorgeous animal that I fell madly in love with her with all the passion of youth. I poured my heart out to her on our long rides round the estate where my family lived. There was a big ornamental lake there and Shadow loved the water, so in summer I used to let her trot in and I’d slide down off her back and hold onto her tail as she pulled me along, deeper and deeper across to the other side. She was my best friend from the age of about seven to ten. I was closer to her than to anyone else, and I have wonderful memories of our adventures together.

Michael’s elder daughter Kate has two boys, Will and Alex, and they used to come and stay with us during their school summer holidays. It was lovely to see them bonding with our horses and I always encouraged it because I wanted them to experience some of the magic I’d had as a child. If there were any foals, we let the boys name them, and they opted for several non-traditional horse names, such as Miriam, Marcus, Wilbur and Doris. No matter. I loved seeing them having fun and learning to love horses as I did.

The family complained about conditions in winter, though. It was a particularly wet part of Devon and it always seemed to be raining, meaning the yard became a sea of mud. Inside the house it was bitterly cold and hurricane drafts swept through the ill-fitting windows. Fireplaces smoked, the walls were damp, and the only way to survive was to wear umpteen woollen sweaters one on top of the other.

One year, the family came for Christmas with us and got a taste of our lifestyle that they didn’t much appreciate after a bay mare called Nellie fell ill on Christmas Eve. I knew at a glance that it was colic so we called the vet, who came out to treat her and told us to keep an eye on her overnight. Colic is a nasty thing, sometimes caused by an impaction in the gut. It can either be cured more or less instantly, or it can develop into something much more sinister. It’s important to make sure the horse doesn’t roll over, resulting in the further complication of a twisted gut. All night I walked poor Nellie up and down the lane in front of the house to try to distract her from the pain and stop her rolling but her whinnying kept everyone awake. Towards dawn, her condition deteriorated and I had to call the vet out again. We rigged up a drip to treat her in one of the stables but, despite our best efforts, she became toxic and had to be put to sleep. I was completely distraught, as well as shattered from lack of sleep.

When the children woke on Christmas morning, we had to break the news to them. I went into their room and was surprised to see clingfilm all over the windows.

‘What’s that doing there?’ I asked.

Kate explained that the bitter north-easterly wind had made temperatures drop to sub-zero and it was like trying to sleep in a draughty igloo. They didn’t want to disturb us and clingfilm was the only thing they could think of to provide a modicum of insulation.

I told them about Nellie and comforted the boys as best I could, then it was time to rush outdoors again for the morning routine of feeding and mucking out. Animals don’t know that it’s Christmas, after all. Late morning, I was sweeping the yard, trying to keep busy to stop myself brooding about Nellie, when Kate popped her head out the door.

‘Erm, Helen …?’ she asked. ‘Any idea when you’re coming in? The kids are all waiting for you so they can open their presents.’

I’d become so one-track-minded, I’d forgotten about Santa Claus and turkey and mince pies. It was a reality check. Horses are wonderful, but so are my family and it was time to find a balance between the two again.

Chapter 4

Lucy and Freddy

At around the time Greatwood became a charity in 1998, the British Racing Industry was coming to accept that it had a responsibility to put a fund in place for retired or neglected racehorses. Only around 300 of the 4,000 to 5,000 racehorses retired annually need charitable intervention, but looking after 300 Thoroughbreds a year is an expensive and labour-intensive job by anyone’s standards.

More and more stories were appearing in the press and the momentum for change was building. Carrie Humble, founder of the Thoroughbred Rehabilitation Centre in Lancashire, together with Vivien McIrvine, Vice President of the International League for the Protection of Horses, and Graham Oldfield and Sue Collins, founders of Moorcroft Racing Welfare Centre, formed part of a well-established racing group and were all influential in the decision that racing should try to help those ex-racehorses that had fallen upon hard times.

In January 1999 the British Horseracing Board Retired Racing Welfare Group was set up, chaired by Brigadier Andrew Parker Bowles, and the first meeting was held at Portman Square in London. It was quite an effort for Michael and me to get there. We lived at least an hour’s drive away from Exeter station, and from there it was the best part of three hours’ train journey to London, which meant we had to head off straight after the morning feed, long before the sun was up, but it was important that we attended come what may.

The debate was lively, to say the least. One old gent told me that in his opinion the best thing to do with ex-racehorses was shoot them. Eventually, though, a consensus was reached. Everyone at the meeting – including leading representatives from all areas of horseracing – agreed that set-ups such as ours were a vital safety net for the racing profession. In recognition of this, it was agreed that the Industry would put in place a fund to provide annual grants to accredited establishments, and Greatwood was to be one of them.

So far so good, but the details were not discussed and we didn’t know when the funding would start or how it would be administered. It was gratifying that our collective voices had at least been heard, but we were still flat out to the boards caring for the horses that were currently in our care and keeping an eye on those that we had rehomed. So in short, yes, we were pleased that our work was at last recognised but, more to the point, when would this support be forthcoming?

Our local paper started a campaign and it was picked up by some of the national media, thus helping to raise our profile, but we continued to live on a knife edge. Each horse cost £100 a week to keep and we had more than twenty in our care at any one time, which meant £2000 a week or £104,000 a year. We were so short of money that we were always just a hair’s breadth away from our overdraft limit and robbing Peter to pay Paul on a weekly basis. We stretched our credit cards to the maximum, but they wouldn’t quite cover the ongoing expenses.

During that time of great anxiety, we really valued our friendship with Father Jeremy and his wife Clarissa. She often brought groups of children to the farm to visit, and she would supply sumptuous picnics that we could all enjoy: cakes with flamboyant coloured icing topped with seasonal decorations, sausages, sandwiches, buns and home-made biscuits. There was always far too much and the leftovers would feed Michael and me for a couple of days afterwards. I suspect she planned it that way.

The horses never seemed to mind little people rushing around whooping and shrieking. Even the most nervous mares that were startled by cars would lower their heads to allow the children to stroke their noses, turning a blind eye to the general mayhem. For their part the children begged to be allowed to ride a horse and, after some consideration, we nominated Chic as the calmest, steadiest one.

Chic was still looking after Jack, her adoptive foal, but she was happy to let the children sit on her back and was careful not to move a muscle when they clustered around her feet. Whenever I climbed on her, she tended to fidget but with the kids she stood stock still. She looked after them just as well as she looked after Jack, always keeping an eye out for him no matter what else was going on.

One day I photographed Chic with several children on her back and sent a copy of the picture to Vivien Mc-Irvine, along with another photo of a group of kids who had climbed a haystack and were jumping off with unfurled umbrellas in an attempt to imitate Mary Poppins. I’d wanted her to see how well it was all going, but the very next day the phone rang.

‘Helen, what on earth do you think you are doing? Do you have any idea of the litigation that would follow if one of those kids falls and injures himself? If there’s an accident, you’d all be for the high jump!’

It shows how naïve I was back then that the possibility hadn’t even occurred to me. I thought it was great that everyone was having such a lovely time and never considered any repercussions. After that I made sure the children always wore hard hats before riding the horses, but I still let them mess around and let off steam. It had to be exciting on the farm or they wouldn’t have wanted to come.

The children came in groups of twelve to fifteen at a time, and it wasn’t all fun and games for them, because I set them to work mucking out, helping with the feeding or sweeping the yard. They didn’t seem to mind because the same few came back time after time, dropped off and picked up by their parents. One Saturday, we got a phone call from a man we knew through the church.

‘I’ve heard you have children coming to the farm to help, and I wondered if we could bring my daughter Lucy?’ he asked.

‘Of course,’ I said straight away, then added quickly, ‘What age is she?’ I didn’t want to end up babysitting for someone I’d have to take to the loo all the time.

‘Fourteen.’

‘That’s fine, then.’

He hesitated. ‘It’s just that … Lucy’s been having a bit of trouble at school. I don’t know exactly what’s going on but she doesn’t seem to have any friends and she’s unhappy. We have to drag her out the door in the morning. I thought maybe she could make some new friends at Greatwood, and be of use to you at the same time.’

My curiosity was aroused. ‘Of course she can come. I look forward to meeting her.’

An hour later, a car pulled into the yard and our friend got out along with a lanky girl with a shock of ginger hair. Her legs were so skinny her kneecaps looked like hubcaps, and when she smiled I saw her teeth were too big for her mouth. She was at an awkward age.

‘Hi, Lucy,’ I said, shaking her hand. ‘There are some other kids mucking out in that barn over there. If you’d like to join them, someone will find you a shovel.’ I didn’t believe in hanging around exchanging pleasantries while there was work to be done. ‘Don’t worry – I’ll keep an eye on her,’ I promised her dad before he drove off.

I left the children in the barn on their own for a bit, then curiosity got the better of me and I sneaked up to listen in to the conversation I could hear in snatches.

‘I know all about horses,’ I heard Lucy saying. ‘I’ve been riding since I was about two years old.’

‘No one can ride at two,’ another kid intervened.

‘Well, I did,’ Lucy said. ‘I’ve ridden lots of racehorses. There’s not a horse I can’t ride. My dad’s going to buy me a horse of my own soon. Maybe he’ll get one of the ones here.’

Her dad hadn’t mentioned any such thing to me and I knew they didn’t have the space or the money to keep a horse, but maybe there was some kind of misunderstanding.

Later that morning, Chic was in the yard and I decided to offer Lucy a chance to ride her. ‘Lucy, I overheard you saying you like riding. Would you like to have a go on Chic?’

She blushed and mumbled something to the ground and I assumed she felt shy with me, and perhaps embarrassed that I had overheard her boasting.

‘She’s out in the yard here. Come along.’

At 15.3, Chic is quite a big horse for a smallish girl. I wouldn’t have let Lucy ride off on her but planned to lead her round the yard on Chic’s back. But as soon as I legged her up, I realised she didn’t have a clue what to do because she nearly fell straight off the other side. I looked up at her face and saw that she was ashen. She was utterly terrified. I don’t think she’d ever been on a horse before and suddenly there she was, more than five feet off the ground, having told everyone she was an experienced rider. The other children were all standing around watching so I knew I had to find a way to get her off without making her lose face.

‘Goodness, silly me,’ I exclaimed. ‘I haven’t got any stirrups short enough for you. I’m sorry but you won’t be able to ride today after all. Do you want to come down?’

I caught her as she slid off Chic’s back and skulked back into the barn again.

Later I told Michael about it. ‘I bet that’s why she hasn’t got friends at school if she’s always boasting and making up stories. Why do you think she feels the need to do that?’

‘They’re a good, loving family. I suppose she just feels insecure for some reason. Are you happy to have her come back and help again?’

‘Of course, yes. The more the merrier. It might be good for her.’

I kept half an eye out for Lucy from then on and I realised she wasn’t stupid – in fact she seemed rather bright – but she was so eager to be liked that she overdid it. If she went up to cuddle a dog, she clung on so hard that it wriggled away yelping. When she approached a hen to catch it, she was too keen and scared it off. She tried her hardest to make friends with the other children, but she did everything the wrong way. If she wasn’t boasting that her dad was loaded, or that she could read a book faster than anyone else, or that she was top of the class, then she was laughing raucously at her own, unfunny jokes. The other children soon began to give her a wide berth, and I didn’t blame them, but the more they tried to avoid her, the harder Lucy tried to make them like her.

I had a groom at the time called Sandy who helped us to train the horses. She was about twenty and Lucy was desperate to get on with her. She was cloying in her affections but still she used completely the wrong tactics. Instead of listening to Sandy’s conversation, Lucy felt she had to impress her with her knowledge of pop music, or computers, or things that were all far too old for her. Whatever Sandy said, she had to go one better. If Sandy had a new CD, Lucy boasted that she had seen the band live in concert. If Sandy mentioned a TV programme she liked, Lucy claimed to have it on video. Sandy was kind to her, but I could tell Lucy annoyed her with her constant wheedling. I knew that inside she was a frightened little girl, but I had no idea how to teach that girl better social skills. Where do you start?

Despite her lack of friends at Greatwood, Lucy was obviously happy with us. One Saturday, her father got out of the car and came over to have a word.

‘Lucy’s mother and I are so grateful for everything you’re doing for her,’ he said. ‘The school holidays are just starting and we wondered if she could spend more time here. Only if she’s useful, of course.’

In fact, she was a good worker, picking things up the first time she was told, and thinking for herself if need be. ‘I’d be delighted,’ I said.

‘I think she might be interested in working with horses when she leaves school, and we want to encourage her in her ambitions.’

‘She should stay here for a couple of weeks and get a taste of the early starts before she makes up her mind about working with horses,’ I quipped, and before I knew it, it had been agreed that Lucy would move in with us for two weeks over the summer. She’d got under my skin and I wanted to help her out if I could.

For two weeks Lucy slept in our spare room, ate her meals with us, and I didn’t for one moment regret the decision. She used to get up with me at 5am to boil the huge vats of barley on our Aga for horse feed. She’d help feed the other animals as well, then wash out the feed buckets, muck out the barns, and keep everything neat and tidy around the yard. She became adept at slipping a head collar on the horses and talking quietly to them when they needed to stand still, for example if the farrier was there to trim their hooves. All in all, she was a great asset to me – but still the other children didn’t warm to her.