Полная версия

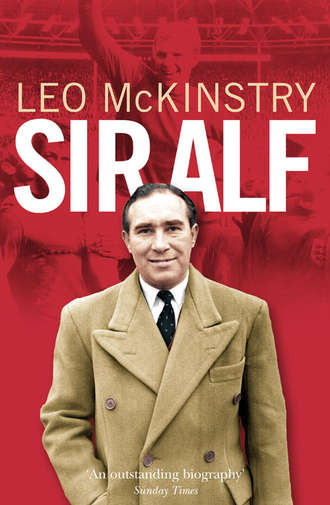

Sir Alf

It was a country life that young Alf relished, especially because it provided such scope for football. He wrote in Talking Football:

Along with my three brothers, I lived for the open air from the moment I could toddle. The meadow at the back of our cottage was our playground. For hours every day, with my brothers, I learnt how to kick, head and control a ball, starting first of all with a tennis ball and it is true to say that we found all our pleasure this way. We were happy in the country, the town and cinemas offering no attractions to us.

But it was also a deprived existence, one that left him permanently defensive about his background. ‘We were not exactly wealthy,’ he admitted euphemistically. His later fastidious concern for his appearance stemmed from the fact that his family was poorer than most in the district, so he was not always dressed as smartly as he would have liked. If anyone commented on this difference, he retreated further into his shell, ‘We grew up together in Halbutt Street. Alf was very introverted, not very forthcoming. I sometimes went to his house, a very old cottage, little more than a wooden hut. His family were just ordinary people. He was not especially well-turned out as a child. That only came later, when he bettered himself,’ says his contemporary Phil Cairns.

Alf’s father, Herbert Ramsey, made a precarious living from various manual activities. He owned an agricultural small-holding, while on Saturdays he drove a horse-drawn dustcart for the local council. He also grew vegetables and reared a few pigs in the garden at the front of Parrish Cottages. He has sometimes been described as ‘a hay and straw dealer’, though it is interesting that when Alf married in 1951, he referred to his father’s occupation as a ‘general labourer’. Others, less generously, have said he was little more than a ‘rag-and-bone man’. Alf’s mother, Florence, was from a well-known Dagenham family called the Bixbys.

Pauline Gosling, who was a neighbour of the Ramseys in Parrish Cottages, recalls:

The cottages had outside toilets and no hot water. If you wanted a bath, you had to heat up the water in a copper pan and then fill a tin tub by the fire. Friday was usually bath night. There was no electricity, so you had to use oil lamps. If you wanted to go out to the toilet at night, you had to take one of those. Alf’s mother was a lovely lady. She and my mother were very close. They were a quiet family, very private, like Alf. They had worked the land for years around Dagenham. My own great-grandfather used to work on the land with Alf’s great grand-dad.

Gladys Skinner, another former neighbour, says:

There was an outside loo in a little shed in their back garden. You could see their tin bath hanging up on the wall outside. They were never a family to tell other people their business. Alf’s mother was a dear old thing. When they were installing electricity round here, she wouldn’t have it, said it frightened her. Alf’s father was also a very nice man. He sometimes kept pigs and we would go round have a look at the little piglets in the garden.

Alf always maintained that his was a close family. ‘My mother is in many ways very like me. Like me she doesn’t show much emotion. She didn’t, for instance, seem very excited when I received my knighthood. But she is very human and I like to think I was like her in that respect,’ he wrote in a 1970 Daily Mirror article about his life. He also felt that, despite the lack of money, his parents had taught him how to conduct himself properly. ‘He told me that he was brought up very strictly and that is why he was such a stickler for punctuality and courtesy. He said that it was part of his upbringing to be courteous and polite to people,’ says Nigel Clarke.

Alf was one of five children. He had two older brothers, Len and Albert, a younger brother Cyril, and a sister, Joyce, though he was the only one to go on to achieve public distinction. Cyril worked for Ford; Len, nicknamed ‘Ginger’, became a butcher; and Joyce married and moved to Chelmsford. Albert, known in Dagenham as ‘Bruno’, was the least inspiring of the siblings, utterly lacking in Alf’s ambition or focus. A heavy drinker, he earned his keep from gambling and keeping greyhounds. Alf himself was always interested in the dog track, liked a bet and was a shrewd gambler. But he never allowed it to dominate his life in the way that Albert did. ‘Bruno was a big chap. I can picture him now, with a trilby turned up at the front. He had a great friend called Charlie Waggles and the two of them never went out to work. At the time I thought that was terrible. They just gambled on the dogs,’ says Jean Bixby, who grew up in Dagenham at this time. In later life, Bruno’s disreputable life would cause Alf some embarrassment.

From the age of five, Alf attended Becontree Heath School. Now demolished, Becontree Heath had a roll of about 200, covering the ages of four to fourteen. Alf was neither especially diligent about his lessons nor popular with his fellow pupils. ‘I was never particularly clever at school. I seem to have spent more time pumping at footballs and carrying goalposts,’ Alf once said. ‘He was a year above me but I remember him all right. Know why? ’Cos he looked like a kid you wouldn’t get to like in a hurry,’ said one of them in a Sun profile of Sir Alf in 1971. For all his introspection, Alf was not a cowardly child, as he proved in the boxing ring at school. ‘I weighed only about five stones, but I was a tough little fighter. I won a few fights,’ he later recalled. But when he was ten years old, he was pulverized in a school tournament by a much larger opponent. ‘He was about a foot bigger than I was and I was as wide as I was tall. I was punched all over the ring.’ That put a halt to his school boxing career, though for the rest of his life he retained a visible scar above his mouth, a legacy of that bout. Alf was also good at athletics, representing the school in the high jump, long jump, and the one hundred and two hundred yards. And he was a solid cricketer, with a sound, classical batting technique.

But, as in adulthood, football was what really motivated Alf Ramsey. ‘He did not have much knowledge of the world. The only thing that ever seemed to interest him was football,’ says Phil Cairns. ‘He was very withdrawn, almost surly, but he became animated on the football field.’ From his earliest years, Alf demonstrated a natural ability for the game, his talent enhanced not only by games in the fields behind Parrish Cottages, but also by the long walk to and from school with his brothers. To break the monotony of the journey, which took altogether about four hours a day, the boys brought a small ball with them to kick about on the country lane. On one occasion, Alf accidentally kicked the ball into a ditch, which had filled with about three feet of water after heavy rainfall. He was instructed by his brothers to fish it out. So, having removed his shoes and socks, he waded in, soon found himself out of his depth, and was soaked to the skin. On his return home, he developed a severe cold and was confined to bed for a week. He wrote later: ‘That heavy cold taught me a lesson. I am certain that those daily kick-abouts with my brothers played a much more important part than I then appreciated in helping me secure accuracy in the pass and any ball control I now possess.’

Alf’s ability was soon obvious to his schoolmasters. One of his teachers, Alfred Snow, recalled in the Essex and East London Recorder in 1971: ‘I was teaching at Becontree Heath Primary and I taught Alf Ramsey for two years. I remember him particularly well because he was so good on the football field. It didn’t really surprise me to see him get where he has.’ At the age of just seven, Alf was placed in the Becontree Heath junior side, in the position of inside-left. His brother Len was the team’s inside-right. Alf’s promotion to represent his school meant that, for the first time, he had to have proper boots. His mother went out and bought him a pair, costing four shillings and eleven pence – with Alf contributing the eleven pence from the meagre savings in his own piggy bank. ‘If those boots had been made of gold and studded with diamonds I could not have felt prouder than when I put them on and strutted around the dining room, only to be pulled up by father. “Go careful on the lino, Alf,” he said, “those studs will mark it,”’ Alf’s ghost-writer recorded in Talking Football.

By the age of just nine, Alf, despite being ‘a little tubby’, to use his own phrase, had proved himself so outstanding that he was made the school’s captain, commanding boys who were several years older than himself. He had also been switched to centre-half, the key position in any side of the pre-sixties era. Under the old W-M formation which was then the iron tradition in British soccer, based around two full-backs, three half-backs, two wingers and three forwards, the centre-half was both the fulcrum of the defence and instigator of attacks. It was a role ideally suited to Alf’s precocious footballing intelligence and the quality of his passing.

His performances brought him higher honours. He was selected to play for Dagenham Schools against a West Ham Youth XI, then for Essex Schoolboys, and then in a trial match for London schools. But in this match, Alf’s diminutive stature told against him. He wrote:

I stood just five feet tall, weighed six stone three pounds and looked more like a jockey than a centre-half. In that trial, the opposing centre forward stood five feet, ten and half inches and tipped the scale at 10 stone. After that game I gave up all hopes of playing for London. That centre-forward hit me with everything but the crossbar, scored three goals and in general gave me an uncomfortable time.

Compounding this failure, a rare outburst of youthful impetuosity led to a sending-off for questioning a decision of the referee during a match for Becontree Heath School. The Dagenham Schools FA ordered him to apologize in writing to both the referee and themselves. He did so promptly, but it was not to be his last clash with the authorities.

For all such problems, Alf had shown enormous potential. ‘He was easily the best for his age in the area,’ says Phil Cairns. ‘He was brilliant, absolutely focused on his game. He was taking on seniors when he was still a junior. Everyone in Dagenham who was interested in football knew of Alf because he was virtually an institution as a schoolboy. He was famous as a kid because of his football.’ Jean Bixby’s late husband Tom played with Alf at Becontree Heath: ‘Alf was a very good footballer as a boy. Tom said that he had great control and confidence. He always wanted the ball. He would say to Tom, “Put it over here.”’

Yet Alf’s schoolboy reputation did not lead to any approaches from a League club. He therefore never contemplated trying to become a professional footballer when he left Becontree Heath School in 1934. ‘I was very keen on football but one really didn’t it give much thought. There was no television then, and football was just fun to do,’ he told the Dagenham Post in 1971. Instead, he had to go out and earn a living in Dagenham to help support his family; this was, after all, the depth of the Great Depression in Britain, which spawned mass unemployment, social dislocation and political extremism. Alf first applied for a job at the Ford factory, where wages were much higher than elsewhere. But with dole queues at record levels, competition for work there was intense and he was rejected. Following a family conference about his future, he then decided to enter the retail trade, beginning at the bottom as a delivery boy for the Five Elms Co-operative store in Dagenham. The occupation of a grocer might not be a glamorous one, but at least it was relatively secure. People always needed food, and the phenomenal growth in the population of Dagenham in the 1930s provided a lucrative market for local businesses. In addition, there was a high demand for grocery deliveries in the area, because public transport was poor.

Alf immediately demonstrated his conscientious, frugal nature by giving the great majority of his earnings to the family household. ‘Every day I’d cycle my way around the Dagenham district taking to customers their various needs. My wages were twelve shillings a week. Of this sum, I handed over ten shillings to my mother, put a shilling in the box as savings and kept a shilling for pocket-money,’ he wrote. After several years carrying out these errands, Alf graduated to serving behind the counter at the Co-op shop in Oxlow Lane, only a short distance from his home in Halbutt Street.

He later claimed to be happy in his job, but what he missed was football. For two whole years, he could not play the game at all, since he had to work throughout Saturday and there was no organized soccer in Dagenham on Thursdays, when he had his only free afternoon. But then, in 1936, a kindly shopkeeper by the unfortunate name of Edward Grimme intervened. Grimme had noticed that a large number of talented Dagenham schoolboy footballers were being lost to the game because of their jobs. So he decided to set up a youth team called Five Elms United. Because of his excellent local reputation, Alf was soon asked to join. He had no hesitation in doing so, despite the weekly sixpence subscription, which left him hardly any pocket money. But he did not care. He was once more involved with the game he loved.

Grimme’s Five Elms United held their meetings on Wednesday evenings and played on Sunday mornings in a field at the back of the Merry Fiddlers pub. Playing on the Sabbath was officially banned by the FA in the 1930s. Strictly speaking, after breaking this rule, Alf Ramsey should have been obliged to apply for reinstatement with the Association, once he became a League player, by paying a fee of seven shillings six pence. ‘I was most certainly conscious that Sunday football was illegal then but it presented me with the only opportunity to play competitive football. Technically, I suppose, never having paid the reinstatement fee, I should never have been allowed to play for England or Spurs or Southampton,’ Alf wrote later. So, in effect, the World Cup was won by an ineligible manager.

Playing again at centre-half, Alf showed that none of his ability had disappeared, despite his two-year absence from the game. In fact, he was physically all the more capable because of his growth in height and his regular exercise on the Co-op bicycle. Tommy Sloan, now one of the trustees of the Dagenham Football club, saw Alf play regularly before the war on the Merry Fiddlers ground: ‘It was quite a good pitch there. All the lads played in the usual kit of the time, big shin guards and steel toe caps in their boots. Alf was a very impressive player. He used to tackle strongly, but fairly. He had a very powerful kick, especially at free kicks. He was subdued, never threw his weight about and was a model for any other youngster.’ Alf himself felt he benefited from the demanding nature of those teenage games with Five Elms, ‘I have often looked back upon those matches. Most of them were against older and better teams but we all learnt a good deal from opposing older and more experienced players. They were among the most valuable lessons of my life.’

It is interesting that many of the traits that later defined Alf Ramsey, including his relentless focus on football, his taciturnity and his attempt at social polish, were apparent in his teenage years. For all the poverty of his upbringing in Parrish Cottages, he had nothing like the usual working-class boister-ousness of his contemporaries. George Baker, who grew up near Halbutt Street and later became head of the borough’s recreation department, told me: ‘I was born within two years of Alf and I knew him and his brothers. As a lad, he was not like the locals. He somehow seemed a bit intellectual, a bit distant. He spoke a little bit better than the rest of us. He was pleasant, but he was different.’ Beattie Robbins came to know him in the thirties, because one of her relatives worked with him in the Co-op: ‘I remember him as well spoken, just as he was in later life. He was very nice, but seemed quite shy. I knew him best when he was about 17. He was polite, dignified, a very reserved person. We once went on a coach trip to Clacton with the Five Elms team and he sat quietly on the bus at the front. He did not play around much like some of the others. His life seemed to be just football.’

As he grew older, Alf appeared only too keen to distance himself from his Dagenham roots. The journalist Max Marquis wrote sarcastically in his 1970 biography of Ramsey, ‘There are no indications that Alf is overburdened with nostalgia for his birthplace…in fact the impression is inescapable that he would like to forget all connections with it.’ His Dagenham contemporary Jean Bixby, who worked with Alf’s brother Cyril at Ford, argues: ‘The trouble with Alf Ramsey was that he tried to make himself something that he wasn’t. He went on to mix in different circles and he tried to change himself to fit in with those circles. Yes, even as a child he was slightly different, but he was still ordinary Dagenham. Then he went away and changed. He was not one of the boys anymore. He became conservative, not like the others who all stuck together. He was one apart from them.’

At the heart of this unease, it has often been claimed, was a feeling of embarrassment not just over the poverty of his upbringing, but, more importantly, over the ethnic identity of his family. For Sir Alf Ramsey, knight of the realm and great English patriot, was long said to come from a family of gypsies. This supposed Romany background was reflected in the family’s fondness for the dog track, in the obscure way his father earned his living and in Alf’s own swarthy, dark features. ‘I was always told that he was a gypsy. And when you looked at him, he did look a bit Middle Eastern,’ says his former Tottenham Hotspur colleague Eddie Baily. Alf’s childhood nickname in Dagenham, ‘Darkie Ramsey’, was reportedly another indicator of his gypsy blood. ‘Everyone round here referred to him as “Darkie” and it was to be years later that I found out his name was actually Alf,’ recalled Councillor Fred Tibble. Even today, in multi-racial Britain, there is less tolerance towards gypsies than towards most other ethnic minority groups. And the problems of prejudice would have loomed even larger in the much more homogenous Britain of the pre-war era. In a Channel Four documentary on Sir Alf broadcast in 2002, it was stated authoritatively that ‘Alf had to put up with casual racism. Dagenham locals believed that he came from a gypsy background and so inherited his father’s nickname, Darkie Ramsey.’

There is no doubt that Alf was acutely sensitive about these claims and this may have accounted for some of his habitual reserve. The journalist Nigel Clarke, who knew him better than anyone else did in the press, recalls this incident on tour:

The only time I ever saw Alf really angry was when we were going through Czechoslovakia in 1973 with the England team – in those good old days the press would travel with the team. We were all sitting on the coach as it drove past some Romany caravans. And Bobby Moore piped up, ‘Hey, Alf, there’s some of your relatives over there.’ Alf went absolutely crimson with fury. He would never admit to his Romany background and hated to discuss the subject. He used to say to me, ‘I am just an East End boy from humble means.’ But it was always accepted in the football world that he was a gypsy.

The rumours might have been widely accepted but that did not make them true. Without putting Sir Alf’s DNA through some Hitlerian biological racial profile, it is of course impossible to be certain about his ethnic origins. Indeed, the whole question could be dismissed as a distasteful irrelevance were it not for the fact that the charge of being a gypsy seems to have played some part both in Alf’s desire to escape his background and in the whispers against him within the football establishment. Again, Nigel Clarke believes that the issue may have influenced some snobbish elements in the FA against him: ‘Alf had a terrible relationship with Professor Sir Harold Thompson. An Oxford don like that could not stand being lectured by an old Romany like Alf. That’s when he began to move to get his power back and remove Alf’s influence.’

Yet it is likely that much of the talk about Alf’s gypsy connections has been wildly exaggerated, even invented, while the eagerness to turn a childhood nickname into a badge of racial identity seems to have been based on a fundamental error. According to those who actually lived near him, Alf was called ‘Darkie’ simply because of the colour of his thick, glossy black hair. In the 1920s in the south of England, ‘Darkie’ was a common moniker for boys with that hair type. ‘The Ramseys were definitely not of gypsy stock,’ says Alf’s former neighbour Pauline Gosling. ‘That is where that TV documentary got it wrong. I used to call him ‘Uncle Darkie’. Alf got his nickname at school, only because he had very dark hair as a young child. It was nothing at all to do with being a gypsy. I know that for a fact.’ Jean Bixby is of the same view: ‘His brother Cyril and I worked in the office at Fords and he was a quiet, decent chap. I have heard it said that Alf was a gipsy, but to know Cyril, I could not believe it. Cyril did not seem to be from gypsy stock at all.’ Nor did the family’s ownership and farming of the same plot of land in Dagenham for several generations match the usual pattern for travelling people moving from one area to another. In fact, some of the land used for the building of the Becontree Estate around Halbutt Street had originally been owned by Alf’s grandfather and was sold to the council. As Stan Clements, who played with Alf at Southampton in the 1940s, argues. ‘I never thought Alf was a gypsy. I cannot see that at all. When I first met him, his entire appearance was immaculate. And gypsies don’t own land for generations.’ Alf’s widow denied that he was gypsy. ‘That wasn’t true. I don’t know where that came from,’ Lady Victoria has told friends. And Alf himself, when asked about his origins in a BBC interview, snapped, ‘I come from good stock. I have nothing to be ashamed of.’

Yet, despite this protestation, there always lurked within Alf a sense of distaste about his Dagenham upbringing. He went out of his way to avoid the subject and seemed to resent any mention of it. Terry Venables, who also grew up in Dagenham and later was one of Alf’s successors as England manager, experienced this when he was selected for the national side in 1964, as he recalled in his book Football Heroes:

When Alf called me into the England set-up, my dad said to me, ‘Tell him I used to work with Sid down the docks. He was Alf’s neighbour and he’ll remember him.’ It sounded reasonable at the time. Now picture the scene when I turned up for my first senior England squad get-together. For a start, I was in genuine awe of Alf, who came over and shook my hand. ‘How are you?’ he asked. ‘Fine, thank you very much,’ I replied. ‘By the way, my dad says do you remember Sid? He was your next-door neighbour in Dagenham.’ Had I cracked Alf over the head with a baseball bat he could not have looked more gob-smacked. He stared at me for what seemed like a long, long time. He didn’t utter a single word of reply; he simply came out with a sound which if translated into words would have probably read something like, ‘you must be joking’. He must have seen I was embarrassed by this but he certainly did not make it easy for me.

Ted Phillips, the Ipswich striker of Alf’s era, recalls a similar incident when travelling with Alf through London:

We were on the underground, going to catch a train to an away game. And this bloke came up to Alf:

‘Allo boysie, how you getting on?’ He was a real ole cockney. Alf completely ignored him, and the bloke looked a bit offended.

‘I went to bloody school with you. Still on the greyhounds, are ya?’ Alf still said nothing.

When we arrived at Paddington, we got off the tube and were walking through the station when I said to Alf:

‘So who was that then?’

And he replied in that voice of his, ‘I have never seen him before in my life.’

It was the change in Alf’s voice that most graphically reflected his journey away from Dagenham. Terry Venables, like several other footballers from the same area, including Jimmy Greaves and Bobby Moore, always retained the accent of his youth. But Alf dropped his, developing in its place a kind of strangulated parody of a minor public-school housemaster. The new intonation was never convincing, partly because Alf was a shy man, who was without natural articulacy and could be painfully self-conscious in public, and partly because his limited education meant that he lacked a wide vocabulary and a mastery of syntax. Hugh McIlvanney says: