Полная версия

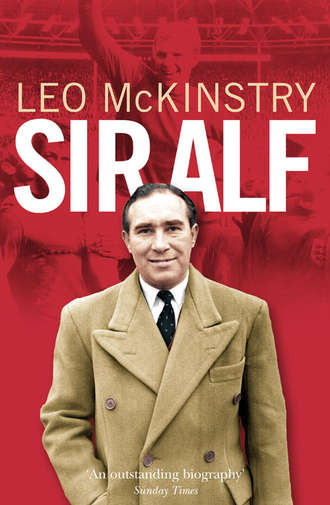

Sir Alf

Yet even now, as nostalgia for the golden summer of 1966 becomes more potent, the memory of Sir Alf Ramsey is not one treasured by the public. He is nothing like as famous as David Beckham, or George Best or Paul Gascoigne, three footballers who achieved far less than him on the international stage. In his birthplace of Dagenham, he seems to have been airbrushed from history. There is no statue to him, no blue plaque in the street where he was born or the ground where he first played. No road or club or school bears his name. The same indifference is demonstrated beyond east London. When the BBC recently organized a competition to decide what the main bridge at the new Wembley stadium should be called, Sir Alf Ramsey’s name was on the shortlist. Yet the British public voted for the title of the ‘White Horse Bridge’, after the celebrated police animal who restored order at the first Wembley FA Cup Final of 1923 when unprecedented crowds of around 200,000 were spilling onto the pitch. With all due respect to this creature, it is something of an absurdity that the winning manager of the World Cup should have to trail in behind a horse. As one of Ramsey’s players, Mike Summerbee, puts it: ‘Alf Ramsey’s contribution to international football was phenomenal. Yet the way he was treated was a disgrace. We never look after our heroes and in time we try to pull them down. I tell you something, they should have a bronze statue of Alf at the new Wembley. And they should call it the Alf Ramsey stadium.’

Part of the failure to appreciate the greatness of Alf Ramsey has been the result of his severe public image. He was a man who elevated reticence to an art form. With his players he could be amiable, sometimes even humorous, but he presented a much stonier face to the press and wider world. The personification of the traditional English stiff upper lip, he never courted popularity, never showed any emotion in public. His epic self-restraint was beautifully captured at the end of the World Cup Final of 1966, when he sat impassively staring ahead, while all around him were scenes of joyous mayhem at England’s victory. The only words he uttered after Geoff Hurst’s third goal were a headmasterly rebuke to his trainer, Harold Shepherdson, who had leapt to his feet in ecstasy. ‘Sit down, Harold,’ he growled. Again, as the players gathered for their lap of honour, they tried to push Alf to the front to greet the cheers of the crowd. But, with typical modesty, he refused. This outward calm, he later explained, was not due to any lack of inner passion but to his shyness. ‘I’m a very emotional person but my feelings are always tied up inside. Maybe it is a mistake to be like this but I cannot govern it. I don’t think there is anything wrong with showing emotion in public, but it is something I can never do.’

Nowhere was Ramsey’s awkwardness more apparent than in his notoriously difficult relationship with the media. Believing all that mattered were performances on the field, he made little effort to cultivate journalists. ‘I can live without them because I am judged by the results that the England team gets. I doubt very much whether they can live without me,’ he once said. Hiding behind a mask of inscrutability, he usually would provide only the blandest of answers at press conferences or indeed none at all. He trusted a select few, like Ken Jones and Brian James, because he respected their knowledge of football, but most of the rest of the press were given the cold shoulder. He also had a gift for humiliating reporters with little more than a withering look. As Peter Batt, once of the Sun, recalls: ‘There was a general, utter contempt from him. I don’t think anyone could make you feel more like a turd under his boot than Ramsey. It is amazing how he did it.’ This hostile attitude led to a string of incidents throughout his career. Shortly after England had won the World Cup, for instance, Ramsey was standing in the reception of Hendon Hall, the team’s hotel in north-west London. A representative of the Press Association came up to him and said:

‘Mr Ramsey, on behalf of the press, may I thank you for your co-operation throughout the tournament?’

‘Are you taking the piss?’ was Alf’s reply.

On another occasion in 1967, he was with an FA team in Canada for a tournament at the World Expo show. As he stood by the bus which would take his team from Montreal airport to its hotel, he was suddenly accosted by a leading TV correspondent from one of Canada’s news channels. The clean-cut broadcaster put his arm around England’s manager, and then launched into his spiel.

‘Sir Ramsey, it’s just a thrill to have you and the world soccer champions here in Canada. Now I’m from one of our biggest national stations, going out live coast to coast, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. And, Coach Ramsey, you’re not going to believe this but I’m going to give you seven whole minutes all to yourself on the show. So if you’re ready, Sir Ramsey, I am going to start the interview now.’

‘Oh no you fuckin’ ain’t.’ And with that, a fuming Coach Ramsey climbed onto the bus.

Such dismissiveness might provoke smiles from those present, but it ultimately led to the creation of a host of enemies in the press. When times grew rough in the seventies, Alf was left with few allies to put his case. The same was true of his relations with football’s administrators, whom he regarded as no more than irritants; to him they were like most journalists: tiresome amateurs who knew nothing about the tough realities of professional football. ‘Those people’ was his disdainful term for the councillors of the FA. He despised them so much that he would deliberately avoid sitting next to them on trips or at matches, while he described the autocratic Professor Harold Thompson, one of the FA’s bosses, as ‘that bloody man Thompson’. But again, when results went against Sir Alf, the knives came out and the FA were able to exact their revenge.

The roots of Sir Alf’s antagonism towards the media and the FA lay in his deep sense of social insecurity. He was a strange mixture of tremendous self-confidence within the narrow world of football, and tortured, tongue-tied diffidence outside it. He had been a classy footballer himself in the immediate post-war era, one of the most intelligent full-backs England has ever produced, and was never afraid to set out his opinions in the dressing-rooms of Southampton and Spurs, his two League clubs. Performing his role as England or Ipswich manager, he was the master of his domain. No one could match him for his understanding of the technicalities of football, where he allied a brilliant judgement of talent to a shrewd tactical awareness and a photographic memory of any passage of play. ‘Without doubt, he was the greatest manager I ever knew, a fantastic guy,’ says Ray Crawford of Ipswich and England. ‘He had a natural authority about him. You never argued with him. He was always brilliant in his talks because he read the game so well. He would come into the dressing-room at half-time and explain what we should be doing, and most of the time it came off. He was inspirational that way.’ Peter Shilton, England’s most capped player, is just as fulsome: ‘From the moment I met Sir Alf I knew he was someone special. He was that sort of person. He was a man who inspired total respect. Any decision he made, you knew he made it for the right reason. He had real strength of character. I have been with other managers who were not as strong in the big, big games. But Alf could rise above the pressure and dismiss irrelevancies.’

Yet Sir Alf never felt comfortable when taken out of the reassuring environment of running his teams. All his ease and self-assurance evaporated when he was not dealing with professional players and trusted football correspondents. He could cope with a World Cup Final but not with a cocktail reception. ‘Dinners, speeches,’ he used to say of the FA committee men, ‘that’s their job.’ Amongst the Oxbridge degrees of the sporting, political or diplomatic establishments, he felt all too aware of his humble origins and lack of education. Born into a poor, rural Essex family, he left school at fourteen and took his first job as a delivery boy for the Dagenham Co-op. To cope with this insecurity, Sir Alf devised a number of strategies. One was to erect a social barrier against the world, avoiding all forms of intimacy. That is why he could so often appear aloof, even downright rude. From his earliest days as a professional, he was reluctant to open up to anyone. This distance might have been invaluable in retaining his authority as a manager, but it also prohibited the formation of close friendships.

Pat Godbold, his secretary throughout his spell as Ipswich manager from 1955 to 1963, says: ‘I was twenty when Alf came here. My first impression was that he was a shy man. I think that right up to his death he was a very shy man. You could not get to know him. He was a good man to work for, but I can honestly say that I never got to know him.’ Sir Alf guarded the privacy of his domestic life with the same determination that he put into management. The mock-Tudor house on a leafy Ipswich road he shared with Lady Victoria – or Vic, as he always called her – was his sanctuary, not a social venue. Anne Elsworthy, the wife of one of the Championship-winning Ipswich players of 1962, recalls Sir Alf and Lady Ramsey as a ‘a very private couple. After he retired, I would occasionally see them in Marks and Spencer’s in Ipswich, but all they would say would be ‘Good morning’. They were not the sort to stand around chatting in a supermarket. When Alf went to play golf, he would just go, complete his round. He would not hang around the bar.’

Another strategy was to reinvent himself as the archetypal suburban English gentleman. The impoverished Dagenham lad, who could not even afford to go to the cinema until he was fourteen, was gradually transformed in adulthood into someone who could have easily been mistaken for a stockbroker or a bank-manager. The pinstripe, made of the finest mohair, was a suit of armour to protect from his detractors. When he went to Buckingham Palace to collect his knighthood in 1967, he went to extraordinary lengths to ensure that he was dressed in the exactly the correct attire. But by far the most obvious change was in his voice, allegedly the result of elocution lessons, as he dropped his Essex accent in favour of a form of pronunciation memorably described by the journalist Brian Glanville as ‘sergeant-major posh’. Like Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion, Sir Alf occasionally betrayed his origins when he slipped into the vernacular of his childhood, as on the embarrassing occasion in a restaurant car travelling to Ipswich when, in the presence of the club’s directors, he told a waitress during dinner, ‘No thank you, I don’t want no peas.’

Tony Garnett, the Suffolk-based journalist who covered Ipswich’s great years under Sir Alf, told me: ‘He did drop some real clangers when he was trying to talk proper, as they say. One of the best was when Ipswich went abroad after they had won the championship and Alf began to talk about going through ‘Customs and Exercise.’ Nobody dared to correct him. He could not do his ‘H’s properly, nor his ‘ings’ at the end of a word.’ With his attempts at precision, his lengthy pauses, his twisted syntax and his frequent repetition of the same phrase – ‘most certainly’ and ‘in as much as’ were two particular favourites – it seemed at times that he was almost trying to master a foreign tongue.

The Blackpool and England goalkeeper in the 1960s, Tony Waiters, who led Canada to the 1986 World Cup finals and has wide experience of working in America, says: ‘It was always worth listening to Alf. But occasionally he would fall down on his pronunciation or would drop an “H” every so often. As a coach myself, I am aware that if you say the wrong thing, it could come back to haunt you. And sometimes Alf would give an indication that this was not his natural way of speaking. He was very deliberate in what he said. I work with a lot of people who are coaching in their second language. Generally speaking they slow down because they are thinking ahead and almost rehearsing in their own mind what they are going to say. With Alf, it was always good stuff but maybe he had to do a bit of mental gymnastics as he prepared to speak.’

For all his anxiety about his accent and his appearance, Sir Alf could never have been described as a snob. Just the opposite was true. He loathed pretension and social climbing, one of the reasons why he so disliked the fatuities of the FA’s councillors. David Barber, who has worked at the FA since 1970, beginning as a teenage clerk, recalls Alf’s lack of self-importance: ‘Right from the moment I first took a job there, I was not in the slightest bit overawed by him. Though he was the most famous man in football at the time, he was down to earth. He was very nice, treated me like a colleague, not an office boy. He was uncomfortable with the press and FA Council members and in public could be a shy man, but with people like me, whom he worked with on a daily basis, he could not have been more friendly.’

Utterly lacking in personal vanity, Alf deliberately avoided the social whirl of London and was unmoved by fashionable restaurants and hotels. His knighthood did not change him in the slightest, while he always retained a fondness for the activities of his Dagenham youth, such as a visit to the greyhound track accompanied by a pint of bitter and some jellied eels. As reflected by his penurious retirement, he refused to exploit his position for personal gain, unlike most of his successors; in fact, it was partly his repugnance at commercialism that led to his downfall.

Alf’s favourite self-preservation strategy, though, was to ignore the world outside and retreat into football, the one subject he really understood. Since his childhood, he had been utterly obsessed with the game. He was kicking a ball before he was learning his alphabet. It was the great abiding passion of his life. When he was truly engaged with the sport, his introversion would disappear, the barriers would fall. Apart from his wife, nothing else had the same importance to him. As his captain at Ipswich, Andy Nelson, remembers: ‘He was a very private, quiet man, very unhappy to have any conversation that was unrelated to football. When we went on the train, we used to have a little card school. Roy Bailey, our goalkeeper, was a big figure in that. Alf would come into our compartment and start talking about football. And then Roy would say, “Anyone seen that new film at the pictures?” You would literally be rid of Alf in two minutes. He’d be off, gone.’ Hugh McIlvanney told me that he could see the change in Alf’s personality as soon as he shifted the ground onto football. ‘Alf liked a drink and he could get quite bitter when he was arguing about football. That front of restraint, which was his normal face for the public, was pretty superficial; he quite liked to go to war. All the insecurity he so obviously had socially did not apply for a moment to football. He was utterly convinced of his case – and with good reason. He was a great manager in any sense.’

It is impossible to deny that, in his obsession with football, Sir Alf was a one-dimensional figure. He had a child-like affection for movies, especially westerns and thrillers, enjoyed pottering about his Ipswich garden and was genuinely devoted to Vickie. But he was uneasy with any discussions about politics, current affairs or art beyond privately mouthing the conventional platitudes of suburban conservatism. An unabashed philistine, he turned down an offer to take the England team to a gala evening with the Bolshoi Ballet during a trip to Moscow in 1973; instead, he arranged a showing of an Alf Garnett film at the British Embassy. He had an ingrained xenophobic streak, and had little time for any foreigners, in whose number he included the Scots. In fact, his dislike of the ‘strange little men’ north of the border was so ingrained that one Christmas, when he was given a pair of Paisley pyjamas as a present, he soon changed them at the shop for a pair of blue and white striped ones.

Nigel Clarke, the experienced journalist who worked more closely with Sir Alf than anyone else in Fleet Street and wrote his column for the Daily Mirror in the 1980s, provides this memory: ‘Alf was certainly conservative with a small ‘c’. But he was not a worldly man and we never really talked about current affairs or wider political issues. He was just happy talking about football. I think that was partly because he knew the subject so well. He could talk about football until the cows came home. He never wanted to discuss governments or religion or anything like that. His life revolved around football. He had little conversation about anything else. His face would lighten up when you mentioned something about the game. We would be sitting in the compartment of a train, going to cover a match for the paper, and Alf would be dozing. Then I might refer to some player and his eyes would open, he would sit up instantly, and say, ‘Oh really, yes, I know him. I saw him play recently.’ He just loved football, loved anyone who shared his passion for it.’

When it came to football itself, Sir Alf Ramsey was anything but a one-dimensional figure. Beneath his placid exterior, the flame of his devotion to the game burned with a fierce intensity. It was a strength of commitment that made him one of the most contradictory and controversial managers of all time. He was a tough, demanding character, who could be strangely sensitive to criticism, a reserved English gentleman who was loathed by the establishment, an unashamed traditionalist who turned out to be a tactical revolutionary, a stern disciplinarian who was not above telling his players to ‘get rat-arsed’. His ruthlessness divided the football world; his stubbornness left him the target of abuse and condemnation. But it was his zeal that put England at the top of the world.

ONE Dagenbam

The Right Honourable Stanley Baldwin, the avuncular leader of the Conservative Party in the inter-war years, was not usually a man given to overstatement. But in 1934 he was so impressed by the new municipal housing development at Becontree in Dagenham that he was moved to write in an official report:

If the Becontree estate were situated in the United States, articles and newsreels would have been circulated containing references to the speed at which a new town of 120,000 people had been built. If it had happened in Vienna, the Labour and left Liberal press would have boosted it as an example of what municipal socialism could accomplish. If it had been built in Russia, Soviet propaganda would have emphasized the planning aspect. A Pudovkin film might have been made of it – a close up of the morning seen on cabbages in the market gardens; the building of the railway lines to carry bricks and wood, the spread of the houses and roads with the thousands of busy workers, gradually engulfing the fields and hedges and trees. But Becontree was planned and built in England where the most revolutionary social changes can take place and people in general do not realize they have occurred.

The Becontree estate was certainly dramatic in conception and scale. It was first planned in 1920, when the London County Council saw that a radical expansion in the number of homes would be needed to the east of the city, in order both to provide accommodation for the men returning from the Great War and to alleviate the terrible slum conditions of the East End. This was to be Britain’s first new town, a place providing ‘homes fit for heroes’. The scheme to convert 3000 acres of land into a vast urban community was, as the LCC’s architect boasted, ‘unparalleled in the history of housing’. The establishment of the Ford motor works in Dagenham in 1929 was a further spur to the urbanization of the area. By 1933, with the building programme reaching its peak, the LCC proclaimed that, ‘Becontree is the largest municipal housing estate in the world.’

Right in the midst of this gargantuan sprawl, untouched by bulldozer or bricklayer, there stood a set of rustic wooden cottages. These low, single-storey dwellings had been built in 1851, when Dagenham was entirely countryside. For all their quaintness, they were extremely primitive, devoid of any electricity or hot running water. And it was in one of them, Number Six Parrish Cottages, Halbutt Street, that Alfred Ernest Ramsey was born on 22 January 1920, the very year that saw the first proposals for the Becontree Estate. The row of Parrish Cottages remained throughout the development of the estate, an architectural and social anachronism holding out against the tide of modernity. They did not even have electricity installed until the 1950s and they were not finally pulled down until the early 1970s. In one sense, the cottage of his birth is a metaphor for the life of Alf Ramsey: the arch traditionalist, modest in spirit and conservative in outlook, who refused to be swept along by the social revolution which engulfed Britain during his career.

For much of his early life, Ramsey was not completely honest about his date of birth. In his ghost-written autobiography, published in 1952, he stated baldly that he was born ‘in 1922’, without giving any details of the month or the day. Now the reason for this was not personal vanity but sporting professionalism. When Ramsey was trying to force his way into League football at the end of the Second World War, a difference of two years could make a big difference to the prospects of a young hopeful, since a club would be more likely to take on someone aged 23 than 25. In such a competitive world, Ramsey felt he had to use any ruse which might work to his advantage. His dishonesty was harmless, and it passed largely unnoticed until after he received his knighthood in 1967. Having been asked to check his entry for Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Sir Alf decided not to mislead that most elevated of reference works. As Arthur Hopcraft put it in the Observer, ‘Alf Ramsey the dignified, the aspirer after presence, could not, I am convinced, give false information to the book of the Peerage.’ But by then the issue of his age had ceased to matter; in any case, because of the stiffness of his character, he had always seemed much older than his stated years.

Parrish Cottages may have become outdated with the arrival of the Becontree Estate, but when Alf Ramsey was an infant they were typical of rural Dagenham, where farming was still the main source of subsistence. ‘Dagenham was like a little hamlet. It was much more countrified until they built the big estate. There was a helluva lot of open space here in the twenties,’ says one of Alf’s contemporaries Charles Emery. ‘Most people think of Dagenham as an industrial area. But until I was six there was nothing but little country lanes. I saw Dagenham grow and grow,’ Alf wrote in 1970. A reflection of that environment could be seen at the Robin Hood pub in the north-west of the borough, where customers drank by the light of paraffin or oil lamps, and the landlord had to double as a ploughman. As one account from 1920 ran: ‘A customer would enter the bar and finding it empty, would shout across the fields for the landlord. After a time he would arrive, and wiping his hands free from the soil, would draw a pint of beer, have a talk about the weather, and then depart again to the fields.’

A striking picture of life in Dagenham in the early twenties was left by Fred Tibble, who died in 2003 after serving as a borough councillor for 35 years. He grew up with Alf, often playing football and cricket with him, and remembered him as ‘a very quiet boy who really loved sport’. The late Councillor Tibble had other memories:

We were very much Essex, we were country people. Many people came to the village selling things. There was a muffin man, who would come to the area once a week, ringing a bell with a tray of muffins on his head. The voluntary fire brigade was based in Station Road in the early 1920s, and when the maroon sounded, men would have to leave their jobs and homes to man the appliances. It could be difficult in the daytime, as they would have to try to get the horse which was being used for the milk round. At the weekends and summer evenings, the police used a wheel-barrow to take drunks from the pub to the police station. The drunks would be strapped into the barrow. We always found that amusing. Sometimes we would climb up the slaughterhouse wall to take a look at cattle being pole-axed. We often hoped to get hold of a pig’s bladder, which we could stuff with paper and play football with.