Полная версия

Round Ireland in Low Gear

We spent most of the voyage re-packing our pannier bags. Sitting surrounded by them in the ferry saloon we looked like beleaguered settlers on the old Oregon trail. It was remarkable how much room two sets of front and rear panniers, not to speak of the stuff sacs, took up when removed from the bicycles. All the contents had to be put in plastic liners as the panniers were not guaranteed waterproof against torrential rain, and since these liners were opaque, once they were packed it was difficult to remember what was in them. We had started off very efficiently at home before leaving, sticking on little labels bearing the legends ‘spare thermal underwear’, ‘boots and spare inner tubes’, and so on, but now Wanda decided on a complete and more logical redistribution, while other passengers looked on with fascination.

It was seven-thirty before we finally disembarked at Rosslare; and a cold, dark evening with the wind driving great clouds of spray over the jetty. We had planned to stay the night there in a bed and breakfast and take a train to Limerick, where we proposed to start our cycling, the following morning, but we now discovered that in winter there was only one train a day to Limerick, and this was due to leave in seven minutes. We had to buy tickets and somehow find something to eat and drink as we had eaten nothing except a cold sausage each and a rather nasty ‘individual rabbit pie’ in a pub since leaving Bristol.

A porter told us to put our bikes in a van at the end of the train. When I had finished locking them up he changed his mind and told me to put them in an identical van at the other end of the train, so I unlocked them and did so. Another man said that was wrong too, so I unlocked them again and took them back to the original one. Meanwhile Wanda was buying the tickets at a reduced rate using our international old age pensioners’ cards. By now, in theory, the train should have left.

The station buffet was warm and friendly, but served no hot food, only ham sandwiches which had to be made-to-measure. Wanda boarded the train while I waited for the sandwiches, but after a minute she got down and rushed into the buffet crying, ‘The train, the train is leaving!’

‘It isn’t leaving, whatever your good lady says,’ remarked a rather quiet man in railway uniform whom I hadn’t noticed before, who was only about a quarter of the way through a pint of Guinness. ‘Not without me, it isn’t. I’m the guard,’ and he took another long draw at his drink. Emboldened by this I ordered a second one myself. Eventually we left more or less on time: the station clock turned out to be about ten minutes fast.

There ensued an interminable journey through parts of Counties Wexford, Kilkenny, a large segment of Tipperary and Limerick, in a hearselike, black upholstered carriage with doors to the lavatories that looked as if they had been gnawed by famine-stricken rats. Outside it was still as black as your hat with a howling wind and torrential rain, and the dimly-lit, battered stations at which the train stopped reminded me of our travels in Siberia. At Wexford our kindly guard, who was in his early sixties, and very old-fashioned-looking in his peaked cap and blue overcoat – infinitely preferable to the ludicrous Swiss-type uniforms affected by British Rail – brought us a jug of hot tea which, after two pints of Guinness in something like five minutes, I was unready for. Meanwhile we spent an hour or so continuing with our re-packing, forgetting which container was which and starting all over again, but this time without an audience.

At Limerick Junction a man with wild hair, a huge protruding lower jaw, wearing a crumpled check suit and looking like a Punch 1850s cartoon of an Irishman joined us in our carriage and began producing unidentifiable items of food from plastic bags.

His meal was interrupted by the arrival of the guard to inspect his ticket, and he spent the next twenty minutes slowly and laboriously going through his pockets and his plastic bags, time after time, without ever finding it. Eventually he produced a 50p piece which he offered to the guard who, by this time bored with the whole business, rejected it. The train – could it be called the Limerick Express I wondered? – arrived at Limerick thirty minutes late, at 11.45 p.m. The weather was still appalling but the area round the station at least still seemed lively and the pubs were still taking orders.

Pushing our bikes through the rain we arrived on the threshold of the Station Hotel, from which the last revellers were being ejected, to find that a double room was £22 a night and the night was half over.

So instead we went round the corner to Boylan’s, part gift shop, part B and B, where we were warmly welcomed and our bikes put in the shop to see the rest of the night through in company with a consignment of nylon pandas. A kindly girl, Miss Boylan, brought tea and cakes – ‘Try and eat them’ she begged, as if we were convalescing from an illness – and we went to bed after a nice hot shower, whacked and surrounded by our mounds of kit.

‘What a fucking day,’ Wanda said before she dropped off. It was difficult not to agree with her.

CHAPTER 3 Birthday on a Bicycle

Nothing in Ireland lasts long except the miles.

GEORGE MOORE. Ave, 1911

(An Irish mile is 2240 yards – an English one 1760 yards.)

As there is more rain in this country than in any other, and as therefore, naturally, the inhabitants should be inured to the weather, and made to despise an inconvenience which they cannot avoid, the travelling conveyances are arranged so that you may get as much practice in being as wet as possible.

W. M. THACKERAY. The Irish Sketch Book of 1842

The next morning I opened a window and was confronted by a painting of a double-headed eagle glaring at me from a wall across what had once been an alley three feet wide, presumably the sign of some former mediaeval hostelry. Rain was falling in torrents and I was in a state of despair and indecision as to what we should do. I could see ourselves sitting in tea shops for days on end waiting for it to abate, playing with nylon pandas and sleeping for endless nights in Boylan’s B and B.

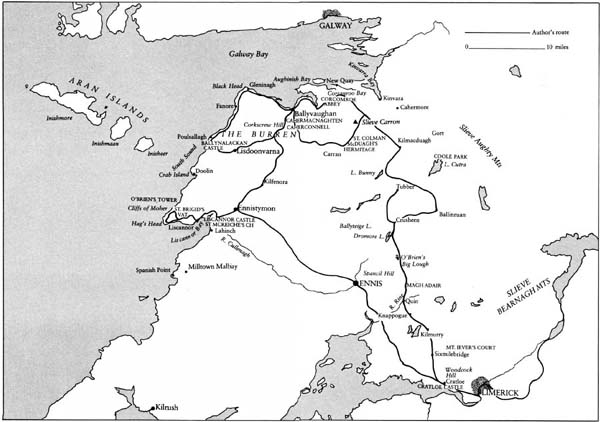

I became even more depressed when 1 suddenly remembered that it was my birthday. Wanda had forgotten it, and this made her depressed, too. Anyway, she gave me a kiss. Then, after a huge breakfast, we sallied out with our bicycles into the terrifying early morning rush hour traffic of Limerick, among drivers many of whom appeared to have only recently arrived in the machine age or were still on the way to it, with Miss Boylan’s warning still echoing in our ears. ‘Be careful, now, on the Sarsfield Bridge, for there are a whole lot of people blown off their cycles on it every year by the wind of the lorries, and kilt!’2

We were heading for County Clare, via the dread Sarsfield Bridge, passing on the way the establishments of purveyors of bacon (bacon is to Limerick what caviar is to Astrakhan) and tall, often beautifully proportioned eighteenth-century brick houses, many of them decrepit to the point of collapse.

It was somewhere in O’Connell Street that Wanda contrived to get in the wrong lane and was borne away on a tidal wave of traffic, crying ‘Hurruck, help me!’ at the top of her voice, although what I was supposed to do to help her was not clear. The last I saw of her for some time to come was disappearing round the corner into that part of the city where stood or used to stand some of the relics of British Imperial rule, such as the County Gaol, the Lunatic Asylum and the Court House of 1810. She finally fetched up back at the station, after which she took a right into Parnell Street and started all over again.

‘You’ve chosen a grand day for it,’ an old geezer about the same age as me said as, reunited at last, we were crossing the Sarsfield Bridge. He let out an insane kind of ‘Heh, heh, heh!’ cackle as an afterthought.

He was wearing a white beard with lovely yellow stains in it that looked like the principal ingredient in a prescription for birds’ nest soup; an ankle-length oilskin coat to match the stains in his beard and a sou’wester ditto, an ensemble that made him resemble the fisherman on a tin of Norwegian-type sardines. I would have hated to live next door to him, in Limerick or anywhere else. ‘Wise guy, eh?’ I shouted after him, but he didn’t get it, probably because his sou’wester was fitted with flaps.

We were pushing our bikes along the footpath, not even riding them, but still being deluged with un-recycled Irish rainwater that was being thrown up by the west-bound trucks whose drivers, deprived of the pleasure of actually ‘kilting’ us, were now doing their best to drown us, and were damn nearly succeeding – the very same men who, reunited with their wives and eight children all under the age of fifteen at weekends, wear subfusc suits and take the collection bags round on the ends of long sticks at Mass, eventually leaving a bundle, and generous bequests to the Society of the Holy Name.

Meanwhile, huge and pale and speckled in the rain, the Shannon flowed on, under the bridge towards the mighty sea, past what looked like a disused Indian chutney factory in Bengal with a tall chimney, and past quays built in the 1870s for what was to be another Liverpool, though it never became one in spite of there being nineteen feet of water off them at high water springs.

Here, the Shannon was 154 miles from its source on the slopes of Cuilcagh Mountain in County Cavan, near the Northern Ireland Border, a place I had promised myself we would visit if we could do so without getting our nuts blown off. At this rate, I wondered if we would ever live long enough to reach it.

Then, suddenly, the rain stopped and the sun came out. Too unnerved by the happenings on the Sarsfield Bridge to really appreciate the fact, we pushed our bikes a few hundred yards or so through suburban Limerick along the N18 to Ennis and points north, then turned off it and rode out into the country on a lesser road between thin ribbons of bungalows, some of them offering yet more beds and breakfasts. And now for the first time we had the chance to appreciate what it was really like riding mountain bikes laden with gear. To me it was much as I imagined it would be to ride a heavily loaded camel, the principal difference being that you don’t have to pedal a camel.

To the right now was Woodcock Hill, a green, western outlier of the Slieve Bearnagh hills; to the left were fields in which donkeys bemoaned their loneliness and battered old trees stood in the hedgerows, and beyond all this to the south was the Shannon, much enlarged since we had last set eyes on it, shimmering in the sun.

A car passed, going in the opposite direction, and the four occupants waved to us cheerily, as did a young man in shirt sleeves, waistcoat and cap who was in a ditch, wielding a fearsome-looking slashing instrument on a long handle that made him look like a survivor of the Peasants’ Revolt.

‘It must be your Jackie Hooghly hat,’ Wanda said. ‘They think we’re Americans.’

The wind was strong and cool, if not downright cold, but at least the sun was shining and the road was flat – well, almost. We were in Ireland at last. There was no doubt about that. In fact we were now in County Clare.

At the village of Cratloe, an avenue led steeply uphill from silver painted gates to a grotto modelled on that of Lourdes, one of the countless thousands erected during 1954, the Marian Year of Special Devotion to the Virgin, decreed by Pius XII. Silver painted gates and railings in Ireland are an infallible sign of the proximity of something Catholic and therefore holy.

To the south of the road was Cratloe Wood. Inside it was wet and dim and mysterious, with long, diagonal shafts of sunlight reaching down into it through the trees. Some of the oaks were descendants of those that had provided timber for the hammer-beam roof of London’s Westminster Hall, when it was built in 1399; and for the roof of the Amsterdam Town Hall, later the Royal Palace, built in 1648 on a foundation of more than 13,000 wooden piles. And long before all this, in the ninth century, men had come here all the way from Ulster to cut down oaks and carry them away northwards to make a roof for the Grianan of Aileach, the summer palace of the O’Neills, Kings of Ulster, on Greenan Mountain, near Londonderry. At some very far-off period the wood had been cut in two by what is now the N18, and another beautiful part of it is still to be found south of this road in a walled enclosure, which forms part of the demesne3 of Cratloe Castle. It belonged to the Macnamaras who, together with the O’Briens, seem to have had more castles in these parts alone – the remains of more than fifty have been identified – than most other families had in the whole of Ireland. At Cratloe itself there are three castles within half a mile of one another, which could constitute some kind of record.

After paddling around in these woods for a bit, wishing we had brought our waterwings, we resumed our journey; but not before Wanda, one of whose foibles is to have no faith in maps, however good, or map readers, however accomplished, had knocked on a cottage door to enquire the way to Sixmilebridge, for which we were bound and to which I already knew the route.

The misinformation she was given by an innocuous-looking old body – ‘Sure, it’s just away down the hill’ – sent her zooming off by herself under a railway line in the direction of Bunratty Castle, the largest of all the Irish tower houses. Had she actually reached it, she would have received no more than her deserts if the directors had put her to work as a serving wench at the mediaeval-type banquets for which they are internationally renowned.

The village of Sixmilebridge bestrode the deep, dark, narrow Owenogarney river. It was really two villages, Old Sixmilebridge on the west bank and New Sixmilebridge on the east bank, built in the early eighteenth century, when an iron works was opened. It had brightly painted houses – a bit like Fishguard – streets with royal names such as Orange, George, Frederick and Hanover, which sounded a bit odd in the depths of republican Ireland, and seven pubs, only one of which served any kind of food, something which seemed extraordinary at the time but which, as we proceeded on our way through Ireland, we came to regard as commonplace. This pub was huge, considering the size of the village. It had three bars, decorated with imitation half-timbering, wallpaper of a sultry tropical design and hue and glass cases containing stuffed, predatory animals. I asked the landlord whether he thought a place the size of Sixmilebridge could really support seven pubs, since I know many villages of a similar size in England that can scarcely support one.

‘Why, yes,’ he said, apparently genuinely surprised by what he obviously regarded as a daft question in a place which in 1931 had a population of 325, and probably had even less now. ‘There’s a living for all of us.’

‘There was no need at all to be chaining your bikes up in Sixmilebridge,’ said a small girl of about seven with a hint of reproof, as we were unchaining them, preparatory to continuing on our way.

We were still only nine miles from Limerick. If we went on like this and I continued to record what I saw in such superfluous detail it would take us five years to travel round Ireland, and the rest of my life to write about it. I put this to Wanda and she said perhaps it didn’t matter, and what other plans had I got for spending the evening of my days; but I knew she wasn’t serious about it. Nevertheless, emboldened by her hardening attitude I talked her into a detour of a mile or two to see Mount Ievers Court, a country house at the foot of the Slieve Bearnagh hills.

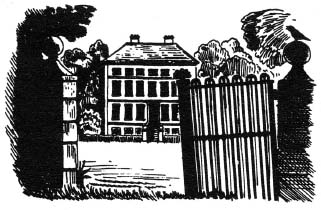

As it was not open to the public, we hid our bicycles near the entrance and approached the house on foot across the park, in which it stood half hidden among trees, some of them enormous beeches, and invisible from the three roads that hemmed the property in.

It was a tall house in every way: three storeys high, with a steeply pitched, tiled roof, tall chimneys, tall doorways and tall windows with white glazing bars. Both its fronts had seven bays and each upper storey was slightly narrower than the one below.

The garden front was faced with bricks of a beautiful pale pink colour and the quoins, the cornerstones, the string courses and the window surrounds were cut from a silvery limestone. A flight of steps led up to a simple doorway on the first floor. The entrance front was entirely faced with this silvery stone, and with what was to be the last of a pale, wintry afternoon sun illuminating the windows the house was an enchanting sight. It could have been the abode of some sleeping princess, waiting to be awakened after a sleep of centuries.

There was no sign of life but we skulked among the trees, anxious not to be detected, certain that if there were any occupants they would not want to be bothered with trespassers in Gore-Tex suits. Neither of us was keen to see the inside in case it failed to equal the exterior of what has been described by Mark Bence-Jones, the author of Burke’s Guide to Irish Country Houses, as ‘the most perfect and also probably the earliest of the tall Irish houses’, but apparently it is well worth seeing.

The house was built by John Rothery and his son Isaac for Colonel Henry Ievers4 sometime between 1730 and 1737, and is thought to have been based on the design of Chevening, in Kent. The beautiful pink bricks used in its construction were brought back as ballast in a vessel that had carried rape-seed oil to Holland, oil that was milled at Oil Mill Bridge, which we had cycled over on our way from Cratloe.

After this detour we set off northwards under what was now a grey sky, bound for Kilmurry and Quin, through a wide expanse of flat, rural Clare with the Slieve Bearnagh hills running away to the north-east on our right.

The road was the site of intensive ribbon development. Along it on either side stood bungalows in an astonishing medley of styles – Spanish hacienda, Dallas ranch house, American Colonial, Teutonic love-nests with stained glass in their front doors, and others in styles difficult to put a name to. Some were already occupied and their windswept, treeless gardens and patios were enclosed with breeze-block walls or with balustrades made from reconstituted stone. Some still had the builders on the premises – their vans and battered cars stood outside and you could hear their owners whistling and their radios on the go. Some were empty shells, abandoned by both the builders and those whom they were building them for, until the present dire state of the Irish economy improved.

If it did, it would only be a matter of time before every secondary road in Ireland would suffer in the same way; many, we subsequently found, already had. These bungalows were alien in the Irish countryside: most of them for instance had no porch in which to hang coats and keep gumboots, an absolute necessity in a place like Ireland. But obviously the Irish love them and they are infinitely better to live in than the damp-courseless, thatched, whitewashed cottages in which their forebears crouched in a single smoke-filled room, stirring some mess suspended over the fire in a blackened pot and fulfilling their destiny by satisfying visitors in search of the picturesque such as ourselves.

Kilmurry, when we finally reached it, having emerged from this Irish subtopia, was a very small place indeed. Of the six roads which met there, five meandered to it across country from points on the map which had no names at all. There were the picturesque ruins of a church and an equally picturesque abandoned churchyard and the sort of picturesque house the Irish were abandoning in droves, with blackbirds in residence in its grass-grown thatch. In the distance the little loughs with which the region abounded sprang to life when from time to time sunbeams forced their way through the clouds that had now gathered overhead.

After this we rode past Knappogue, a Macnamara castle. It was open (morning and afternoon teas were served), and providing a quorum could be found ready to participate, mediaeval banquets could be served at the drop of a hat. But according to the Blue Guide, although built in 1467 it had since been over-restored, not by some Victorian nutcase, as might be expected, but in 1966. So we gave it a miss and pressed on to Quin, a pretty, rural village, with two long, picturesque barns; across the road from Malachy’s Bar.

It was three-thirty, and mad for a pot of tea we entered the bar, in which two locals were drinking Guinness and playing darts. They immediately offered to play a foursome, but we were too thirsty to do anything but drink tea and eat a bit of cake, brought by a young girl, for which we paid an Irish punt (or pound). While doing so I tried to imagine a couple of foreigners entering one of our local pubs in Dorset at three-thirty on a winter’s afternoon and finding customers inside, drinking and offering to play darts, and then being provided with tea and cakes; but I failed. Malachy’s Bar may not have been all that much to look at – inside it resembled a 1935 Wardour Street half-timbered film set – but its occupants were kind and welcoming and I realized that if we were going to attempt to equate aesthetics with happiness while travelling through Ireland we might just as well give up and go and be miserable in the comfort of our own, lovely home.

Outside, on a bank of the little River Rine were the impressive ruins of the Franciscan Abbey founded and built in the fifteenth century by Sioda Cam Macnamara within the perimeter of a Norman castle which had been destroyed, presumably by the Macnamaras around 1286. Other members of this clan were also buried here, among them the Macnamara of Knappogue castle who, had his precise location been known to its restorers, would probably have been dug up and restored too.

Those Franciscans were extremely tenacious. In 1541 they were expelled from their premises, as were other religious communities in Ireland, by Henry VIII in his new guise as King of Ireland and Head of the newly established Protestant Church of Ireland,5 but after the death of Elizabeth I in 1603 the monks returned. In 1649–50 Cromwell initiated his ghastly campaigns in Leinster and in Munster, of which County Clare formed a part, together with what are now Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary and Waterford. The following year, 1651, they were again driven out and in 1652 eleven years of rebellion by the Irish came to an end. In the course of them one third of the Catholic Irish population had been killed; uncounted thousands were shipped to the West Indies, to all intents and purposes to work as slaves; Irish towns were repopulated with English men or English sympathizers; and twenty million acres of land were expropriated and handed over to Protestant settlers.

In spite of these horrors the Franciscans of Quin appear to have been more or less ineradicable. Although driven out of their Friary they contrived to remain in the neighbourhood for the next 150 years. The last surviving member of the order at Quin, Father John Hogan, died in 1820 and his tomb is in the north-east cloister.

Up to now Wanda had been doing very well with her cycling, but after tea at Malachy’s Bar some of the fight appeared to go out of her and when I suggested that we should go and look at Danganbrack, perhaps the most extraordinary of all the fortress houses of the Macnamaras, which the Shell Guide said was three quarters of a mile east-north-east, and which I said, having been there twenty years previously, was only half a mile north-north-east, she said, ‘All right, providing you’re sure it isn’t five miles,’ but without much enthusiasm. But then she hadn’t seen it, as I had twenty years ago.

Then, I had reached it by a tree trunk bridge over a deeply sunken stream at the end of a very muddy track which ran east-wards from a road that led due north from Quin to nowhere. There, in a field, I saw what was known as the ‘ill-fated tower of Mahon Maechuin’, in which the Cromwellian troops, after taking it, spent some time refreshing themselves before moving on that night in 1651 to sack the Abbey. One woman escaped from the tower to bring news of what was happening to Hugh O’Neill, the beleaguered defender of Limerick, which at that time was invested by a Cromwellian army commanded by Henry Ireton until, after six months, he died of the plague.