Полная версия

Gold Rush

After six years of intensive training and competitive dominance, I was ready. More than ready. Before the Olympics as usual I’d done my training in Waco, Texas, where my coach Clyde Hart was still the head track coach for Baylor University. I trained there just about every day. During the final week, instead of pushing hard, we focused on the technical elements of the race. We wanted to let my body rest so that it would be fresh for competition. Just days before a competition all of the work has been done, and if it hasn’t it’s too late to make up the deficiency.

That week I worked on my start out of the blocks, which was never as good as it should have been or as I wanted it to be. The workout, which I had done many times before, was also designed to keep my speed up and to keep me technically sharp. After my warm-up for this particular workout, Coach asked me if I wanted to put on my spikes for the 200-metre portion of the workout. Normally I would definitely wear lightweight spikes for a session requiring me to hit those kinds of times, but this time I decided to wait until we did the starts, even though wearing flats (regular running shoes) would be a disadvantage.

We had a timing system called ‘the beeper’, which would sound every few seconds during our training sessions to help me ascertain whether I was on the pace the session required, and also whether each interval run was accurate. Just like a metronome that helps musicians develop a rhythm with the music, the beeper helped me accurately measure my speed, so I could pace myself correctly and not go too fast or too slowly. This was critical, since a workout session that calls for three 200-metre sprints to be run in 23 seconds is more effective if each run is actually 23 seconds as opposed to one being 21 seconds, one being 25 and one being 23.

For 15 years I’d heard the beeper, which was wired into the Baylor University track’s loudspeakers. I had come to rely on it so much as an essential part of my training that I had my own portable beeper made so that I could take it on the road when I trained away from Waco.

On this particular day I started my first 200-metre run with the beeper set for a 23-second run. I took off. At the 50-metre cone I noticed that I was a little ahead of the beeper. Even so, I maintained my pace. I expected that I would be about the same amount ahead at the second cone, but I was a bit more ahead. I relaxed a little to meet the 23-second goal, but came through the third cone even further ahead. At this point, even though I usually did exactly what Coach’s workout called for when it came to times, I decided not to slow down.

I crossed the finish line figuring that I would be about one second ahead and started to count. ‘One thousand one.’ No beep. ‘One thousand –’ The beep finally sounded. I was 1.5 seconds fast. 21.5. Not an amazing time, given that I had set the world record a month earlier at 19.66 seconds, but to have done it in a training run, during which I’d tried to relax to get back to 23 pace for the last two thirds of the interval, confirmed that I was in the best competitive shape of my life.

After I finished the run, I saw Coach in the middle of the infield with his stopwatch. He didn’t say anything. Normally he would tell me to get back on pace, but this time he remained silent. I walked and kept moving as I always did during the 90 seconds between intervals.

‘Thirty seconds,’ Coach announced, indicating that one minute had passed and I had just 30 more seconds of rest so I should start moving back towards the starting line. Ninety seconds rest means 90 seconds of rest. Not 100 seconds, not two minutes, but 90 seconds of rest. So you don’t start walking to the starting line at 90 seconds. You start running at 90 seconds.

I walked to the starting line and got into start position. The beeper went off and I took off running. I know from experience that the first 50 metres starting from a standing start takes more effort than the other three splits between the other cones, since those segments are from a running start. So normally you start with a little more effort, then settle into a pace and try to relax and maintain it. Since I had run ahead of pace on the first segment of the first interval, I adjusted down and didn’t start as aggressively. I passed the first cone at 50 metres. The beeper didn’t sound until half a second later. Exactly the same as last time.

‘Adjust down,’ I thought. However, it’s mentally tiring to keep making adjustments during the training session intervals, so I decided to maintain my pace. Besides, I was excited about the challenge of maintaining that pace and that distance ahead of the pace not only for the remainder of that interval but for the third one as well. I finished with about the same time as my previous training intervals – 1.5 seconds ahead by my count.

I looked over at Coach and he said nothing again. I felt really good. I realised I was fitter than I had ever been, because although the final interval was coming up in less than 90 seconds, I knew I could run it in 20 seconds if I wanted to. I wouldn’t, since that would be full speed and we never run full speed in training. But the capacity was there.

I started the final 200 and ran just under full effort after having already completed two intervals in the last five minutes. I was well ahead of the first cone when the beeper went off, and it felt effortless. The gap grew at 100 and 150. When I reached the cone at 200 metres, I was 2.5 seconds ahead by my count. That would be 21.5 on the first interval, just under 21.5 on the second and 20.5 on the third.

I started to walk around the track. Coach would normally walk over to join me for the 200 metres back to the starting line side of the track, during which we would talk about how I felt and he would tell me my exact times. This time he didn’t. Instead, he walked into the office at the track under the stands. By the time I reached the other side of the track, Coach was walking out of the office, his training log in hand. ‘Start your cool down,’ he said. Then he showed me the stopwatch. The actual times were 21.4, 21.2 and 20.1. ‘And you weren’t wearing spikes,’ he said.

Coach and I are a lot alike. We expect the best effort, and if that effort is your best, then even if it is as impressive as what I’d just done there’s no reason to get all giddy and celebrate. Our attitude was that I had done what I was capable of, so that’s what we should have expected. I work with one athlete now who always tells me, when I ask him how training is going, that he and his coach feel they are ahead of schedule. To me that means your schedule is wrong and you need to adjust it! Still, my coach and I both agreed that my accomplishment that day confirmed that I was ready to do something really special in Atlanta the following week. ‘The hay is in the barn,’ he said. ‘We’re ready.’

Even so, I sure wasn’t going to assume that I would medal. As I’d learned in 1992, I could do everything right and still not win Olympic gold or any other colour. Something out of my control could happen again. Or I could screw it up myself this time.

TIME TO MAKE IT HAPPEN

On the morning of the 400 metres final, having successfully gotten through and winning the first three rounds over the prior three days, I woke up ready to win my first individual Olympic gold medal. I was the overwhelming favourite. Even though I’d be racing against top competitors, including my US team-mate Alvin Harrison, two Jamaicans – Roxbert Martin and Davian Clarke – and Great Britain’s Roger Black, who had also been running well, everyone expected me to win.

I hadn’t lost a 400-metre race since I was in college over six years ago. Still, I never took my competition for granted. I didn’t believe that any of the athletes in the final could beat me, but I was always aware that there’s more to winning a race than being better than the competition. To win races you have to execute, and one little mistake can cost you a race. If something went wrong in this one, would I even be able to race in another four years when the Olympics rolled around again?

On race day I ordered breakfast through room service and began to lay out my uniform, competition number, socks, spikes, music player, headphones, and everything else I would need at the track. Then I sat in my room for the rest of the day visualising almost every scenario that could possibly happen in that final and devising a plan for what I would do in each scenario.

Although we had travelled to the track from the hotel three times prior to the 400 metres final and had gotten the routine down, I wanted to get to the track early, as much to ensure that I was there in plenty of time as to get out of the room. Even though I had always hated waiting all day for a race because I was so ready to run, I usually didn’t allow myself to leave my room until it was time to go to the track. But this time heading out early gave me the illusion that I could make race time come quicker.

Finally it was time. I finished my warm-up and prepared to report to the ‘call room’, a holding room where all athletes in the race are required to report and wait together just before being taken out to the track for the start of the race. Just before walking over, Coach pulled me aside and we prayed together as we had done since I was in college. I had heard other athletes ask God to let them win, which I thought was ridiculous. Coach, however, simply asked God to keep me healthy and, if it was His will, to allow me to run at my best. ‘God blessed me with this talent,’ I thought as the prayer ended. ‘His job is done, and it’s up to me and me alone to win this race.’

Coach and I had debated about whether to go for a fast race and possibly a world record in the 400 metres final if I was winning at the halfway point, or to run conservatively since after just a day of rest I had to be ready to run the 200-metre races. The 200 metres would be the more difficult challenge, not only because the competition was tougher but also because it would come after four days of gruelling 400-metre races. ‘The decision is yours,’ Coach said before I got on the bus that would take us from the practice field to the Olympic stadium five minutes away. I ran through both options in my head and thought, ‘Stick to the plan. Don’t get distracted with the opportunity to break a world record. There will be plenty of time for that. Win an individual gold medal.’

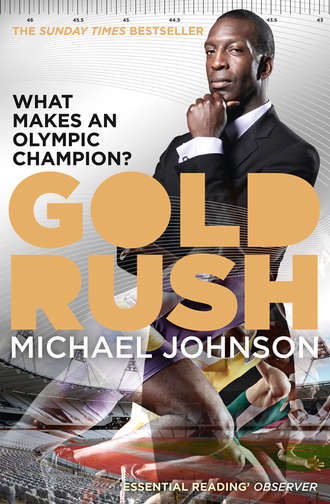

GOLD MEDAL, GOLD SHOES

I had gotten used to the overwhelming flickers of cameras and the applause each time I walked into the stadium. The attention arose not because I had become the face of the 1996 Olympic Games or because I had announced that I would make history. The attention derived from my decision to wear bright, shiny, gold track spikes, designed for me by Nike. The shoes were unlike anything ever made for a track athlete. The technology and design that went into making these shoes and the time spent, over two years, working on them to make them perfect was incredible. The fans and the media, however, focused on the fact that they were gold and looked like nothing anyone had ever seen before. One magazine actually did an entire story just on those shoes, which could be seen from the top of the Olympic stadium. Opting for gold shoes could have been considered downright cocky, but I was confident and never doubted my ability to deliver gold medals to match my shimmering footwear.

The gold shoes project with Nike had actually started as a result of Nike sprint spikes falling behind those of companies like Mizuno in terms of quality, technology and performance. The last straw had come during the 1993 World Championships when the Nike sprint shoe of 400 metres Olympic gold medallist Quincy Watts came apart in the final 100 metres of the race. He placed fourth in the race and blamed his damaged Nike shoe, which he showed to the world on camera in his post-race interview.

At that point Nike had been making my shoes for three years. Basically they had shoes available to anyone to purchase; Nike athletes would choose from that line of shoes and Nike would make them in whatever colours an athlete wanted, adding their name or any other desired graphic on the shoe. So the customisation of the shoe was purely aesthetic. I had used the same Nike model – a very lightweight shoe with a lot of flexibility that Nike had been making since the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics – from the time I was in university. By 1990, however, Nike had stopped making this shoe and had moved on to much more rigid shoes that were designed to help the athlete’s foot strike and recover in a much more efficient way that required less effort. But these shoes were heavy and stiff. I preferred something that would work with my foot and the track.

Although they were no longer selling the shoe I liked, Nike had taken all of the plates (which are the bottom part of the shoe that actually holds the spikes) that they had left in my size and held them in order to make the shoe just for me. Then, at the beginning of 1995, they approached me about a project to highlight the fact that they had overhauled Nike sprint shoes. In our first meeting about the project, they asked me what I liked about my current shoe and why I liked those attributes. ‘What would you want in a shoe if you could have anything you wanted with no limitations?’ they asked. After I answered, they set out to deliver just that.

Throughout the two-year process the focus was on developing something that would not only be unique to me but would help me perform better by being based on my specific needs, given my body mechanics and the events that I competed in. At one 200-metre race Nike set up high-speed cameras all around the track that were focused on my feet from start to finish. The cameras allowed us to view the actions of my feet during a competition at 1,000 frames per second. This allowed us to really understand the movements of my feet and how the shoe interacted with my foot and the track. We found that the interaction was different on the bend from what it was on the straight. We found that it was different for the left foot versus the right foot. We found that it was different for the 200 metres versus the 400 metres. So we accommodated for all those particulars and developed one pair of shoes for the 200 metres and a different pair for the 400 metres. In both pairs of race shoes, the left shoe differed from the right.

Over that two-year period I would meet with a team of shoe designers about once every month. As we got closer to the 1996 season we met even more frequently. They would come to the track with huge bags of prototypes, using all different kinds of materials, for me to try during training sessions. I would give them feedback and they would make adjustments.

Once we finally settled on a material, the project became really fun. With Nike having invested so much time, money and resources to develop a one-of-a-kind, revolutionary sprint spike, it was a given that the shoe that would make its début on the most popular athlete in the sport as he attempted to make history in the Olympic Games, in front of the biggest consumer market in the world, must look cool, different and special. Nike had been known for years for its marketing mastery and branding genius, and now I got to be part of their decision-making process.

We considered a number of looks, including a clear shoe that made it look like I was wearing no shoes at all. One of the looks we narrowed down to was a reflective, mirror-like finish. Up close it was very shiny and looked really cool. We all liked it. ‘It’s so bright that it’ll stand out and be visible even to people sitting high in the stadium,’ one person said enthusiastically.

As I sat in the meeting and thought about that I asked, ‘Do you guys think it might look silver?’ After silent thought and a minimum of debate, we agreed that a shoe that looked silver would be a problem, given our objective.

‘They should be gold,’ I thought to myself. Then Tobie Hatfield, a brilliant shoe designer who was the lead on the project and who remains a very good friend of mine today, looked at me and said, ‘What do you think about gold?’

I have never been a flashy person. I never wore a lot of jewellery, only a simple gold necklace which I bought with one of my first cheques after I started my professional career. I wore that necklace as something of a good luck charm during every single race in my career and stopped wearing it after I retired. And I also wore a simple gold hoop earring when running the 200 metres and a simple diamond stud when running the 400 metres. So while I don’t think anyone would describe me as flashy, they wouldn’t characterise my dress or my image as boring or drab. They both pretty much follow my personality. I’m confident but not brash. And while I like to perform efficiently and effectively, that certainly doesn’t mean that I’m conservative, either in my running or in my style.

The Nike design team left the meeting, saying that they would return in a month or so with a gold version of the shoe. I never thought once during that time that the shoes would get as much attention as they did or that people would remember them decades later. I never looked at them as a statement; nor did I think even once about the consequence of losing while wearing gold shoes. Failing to capitalise on the amazing opportunity to make Olympic history at home would far overshadow any embarrassment over wearing gold shoes during that attempt. The big question was not whether the shoes’ aesthetics would make history, but whether I would. I was about to find out.

RUNNING MY RACE

At ten minutes to the scheduled start time I went through my normal routine, setting my starting blocks and doing one practice start. That was all that was needed. In the 400 metres the start out of the blocks is not as important as in the 200 metres. Because of its greater length there are lots of decisions that have to be made during the race. The critical objective is to limit or if possible eliminate any mistakes. So, after my one practice start, I sat on the box indicating my lane number behind my blocks and ran though the race again in my mind as I waited.

As I sat there waiting for the start, I took the opportunity to look into the stands to get a sense of the atmosphere. The stadium was full, and it made me think for a brief moment about the fact that I was about to win my first Olympic gold medal. That, of course, made me think, ‘In order to do that, you can’t make any mistakes.’ So I turned my attention away from the crowd and back to the race, which was about to start.

The gun went off and I started to execute my race strategy, getting up to race pace as quickly as possible with a good, fast start. The first phase of the race went really well – I made no mistakes and nothing unexpected happened. Feeling comfortable on the back stretch, I tried to relax even more. I focused on Davian Clarke, two lanes outside of me in lane six, because he was normally a fast starter. He didn’t seem to be taking much out of the gap between himself and Ibrahim Ismail Muftah of Qatar outside of him. That signalled to me that the athletes outside of me were not running very fast. Then I started to try to get a feel for where Roger Black was behind me. I couldn’t look backwards since that would throw me off my own pace, so I started trying to see if I could feel his presence. When I did, I realised that I really wasn’t running as fast as I wanted to and I might be a bit off my desired pace.

Normally I would make up the time in the 200 to 300 phase by running harder than normal, but I knew I was in really good shape and I really hadn’t felt any fatigue at all at this point. So I adjusted immediately and at about 180 metres started to run at the speed and effort that I would normally move up to at 200 metres. I also decided to really double down on this strategy, and run even faster in this phase than originally planned. I passed the Jamaican Roxbert Martin, then his compatriot Davian Clarke. Ibrahim Ismail Muftah in lane seven dropped out of the race at about 275 metres. As I went around the curve I could only see Iwan Thomas from Great Britain out in lane eight. When I came out of the curve and out of the third phase of the race and went into the final phase with 100 metres to go, I was far ahead of the rest of the field. I knew that I would win this race big.

I continued to sprint down the track just trying to maintain my technique. Normally with 75 or so metres to go, a little bit of fatigue starts to set in. I never felt the least bit tired that day. Since I knew I was going to win the race for sure, I decided to go for the world record of 43.29. I gave it everything I had, crossed the finish line and immediately looked at the clock – 43.49 seconds, my third fastest time ever but still two tenths off the world record. I knew exactly where I had lost it. In the second phase from 75 metres to 150 metres I had relaxed far too much and I knew it.

I thought about that for a second, then realised I had accomplished what I wanted. I had won. I was the Olympic gold medallist for the 400 metres. I no longer had to fear finishing my career as one of the greatest sprinters never to win an individual Olympic gold medal. That brought a smile to my face. I turned around and saw Roger Black, from Great Britain, for whom I’d always had a lot of respect. The look on his face told me he had won the silver medal. We shook hands and congratulated one another.

On my victory lap I started thinking about the 200 metres. I wasn’t worried about how I would hold up. ‘I could go out right now and run the first round of the 200 metres,’ I told the press during my post-race interview. I wasn’t exaggerating. I felt that good.

Before the medal ceremony, I was still thinking about the 200 metres as I walked around the holding room. The 400 metres had seemed like a formality, something I had to do before I could get to the 200 metres and make history by becoming the first man to win both in an Olympics. Then Roger came in, his excitement evident. When I mentioned the 200 metres, he said, ‘Michael, savour this moment. This is special and you’ll want to remember this for the rest of your life.’

He was right. As we walked to the podium, I thought about my parents and brother and sisters in the stands and how much they had knowingly and in some cases unwittingly supported me. I was the youngest, and my three sisters and my brother would always chase me around and tease me. I had to get fast!

I turned and saw my family in the stands waving at me. As I stood on the top of the podium, Roger’s words crossed my mind again. I looked at the stadium and thought about the fact that I was in Atlanta, in my own country, about to receive my first individual Olympic gold medal. After the officials hung the gold medal around my neck and the US national anthem started to play, I kept thinking about the medal I had just received, where I was and what I had just accomplished. And though I try to be in control and private at all times, I allowed myself to let go and feel the joy, the pride and the relief. That’s when I started to cry. I knew that everyone in that stadium and watching me on television could see me, but I didn’t care.

I celebrated with my family and friends at a restaurant that night, but couldn’t really enjoy the occasion because I knew I wasn’t finished. I had the 200 metres coming up and my competitors were certainly not out partying less than two days before the start of an Olympic competition. So I returned to my hotel and climbed into bed.

TRYING TO MAKE HISTORY

After a day of rest, I awoke really early because I had a morning start time for the first round of the 200 metres. I liked morning start times because I didn’t have to wait around all day. The quarter-finals would be later that evening. I also liked the idea of getting two races done in one day. Both races went very smoothly. As always, I used them to work on my start and the first 60 metres of the race, during which I tried to make up the stagger on each of the athletes outside of me as quickly as possible as we went around the curve.

The following evening, after winning both rounds the day before, it was time to run the semi-final and final. Normally the semi-final is held in the morning or early afternoon and the final much later in the evening. Instead, we would have less than two hours between the races. Regardless, this would be the day when I would either succeed or fail at what I had set out to do.