Полная версия

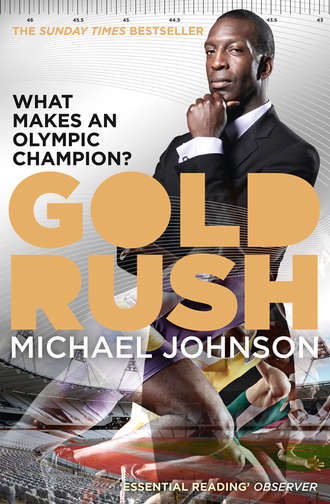

Gold Rush

I took two years away from sport from the age of 14 when I first started high school. My school was a special career development school that only accepted the best of the kids who applied, and each student chose a career focus from many different offerings. At the time I dreamed of becoming an architect, so I spent half of the day learning about that particular career. Eventually I missed sport and came back to track.

When I started competing again at the age of 16, having not played any sports for two years, I had made a big leap in my athletics development, in large measure because I had matured physically. I was immediately winning races easily and working hard which had become standard procedure for me. But I still wasn’t winning every race and I still hated that. In my third year of high school I had won every race until the district championship which I lost, finishing third, and it ended my season. Roy Martin and Gary Henry, who were older than me by one year and in their final years of high school and also very good athletes, had both finished ahead of me.

GOOD COACHING HELPS

The more I thought about why I had lost, the more I put together different things I had heard from other people about the impact that good track coaches who trained their athletes all year could make. My coach, Joel Ezar, was a wonderful man with whom I had a great relationship. But he was not a great track coach; he was a football coach who coached track in the spring when the football season was over. So I simply wasn’t as ready as those other athletes I was losing to. In addition, they knew more about what they were doing on the track than I did.

I didn’t know what to do about the coaching gap, but believed that I could solve it by working harder. The next year, my final year of high school, two other athletes/friends and I began to go out on our own after school and run. We didn’t really know what we were doing but we didn’t know that. We just felt that if we worked in the autumn instead of doing nothing we would be better in the spring.

I hadn’t yet developed my absolute hatred for losing (rather than mere dislike of it). Even so, I was always looking for a way to prevent myself from losing. Throughout my life, as I matured and moved from one level of training and competing to the next, it became clearer exactly what I needed to do to be the best I could be. I just always believed that if I was the best I could be, I wouldn’t lose.

I’ve always said, and I always tell athletes, that if you run your best race and you lose, you have nothing to be ashamed of or disappointed in. I still believe that. But I, personally, never had a loss where I felt it was my best race. Even when I competed to my best ability in high school and lost, I didn’t feel it was my best race because I didn’t feel I was as prepared from a training standpoint as I could have been. A big part of my decision when I was deciding which university to compete for was which coach would be able to help me achieve my best.

In spite of not having a real track coach during my high school career, I still managed to win both the district and regional championships. At the state championship I finished second in the 200 metres behind Derrick Florence, who still holds the high school record for 100 metres and to whom I would never lose again. I wasn’t happy about not winning, but I was more excited that I would be competing at college than I was disappointed that I had lost the state championship.

Originally I viewed the track scholarship I’d accepted from Baylor University only as a means to go to a better college than I would if I had to pay for it myself. But in 1986, between high school and college, I finally start thinking about professional track. I was working in an office that summer, when I started seeing newspaper headlines about the US Olympic Sports Festival in Houston. Reading about Carl Lewis, Calvin Smith and Floyd Heard arriving in Houston to compete in this high-level competition triggered my initial aspirations to run and compete professionally. After finishing the article I found myself for the first time daydreaming about competing against the best in the world and envisioning myself being at this competition with these athletes. I started to really believe that I could be great, because I knew that I hadn’t reached my full potential in high school.

At Baylor University I was in a serious training programme for the first time. It was tough in the beginning. I hated the weight workouts, which I avoided. But I loved training on the track each day and looked forward to it. I approached each day like a competition because I could feel myself getting stronger and better.

AIMING HIGH, HIGHER, HIGHEST

Even though I made some great strides during my first year, I got injured at the end of the season and wasn’t able to compete in the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) university championships. So the following year I focused on becoming an NCAA champion. I hadn’t even considered higher-level competition – let alone the Olympics – until one of my team-mates, Raymond Pierre, went on to compete in the US national championships after the college national championships. Raymond did really well at the US championships, finishing fourth in the 400 metres. This earned him a position on the US national team for the 1987 World Championships, which would be held later in the summer in Rome. Raymond spent most of the summer in Europe competing on the international circuit and once competed as an alternate for the US team, running in the preliminary round of the 4 x 400 metres relay team that won the gold medal.

The day he returned from Rome, school had already started and the team had already started training. Raymond came out to the track wearing a USA team uniform shirt. The only way to get your hands on any official USA track team gear was to make a US team, which was a great accomplishment, so having the gear was a badge of honour. I had seen in my freshman year a handful of athletes from other universities who had competed on US teams wearing USA team gear, and I wanted that. It seemed really cool, because it showed the accomplishment, and signified how good the athlete was.

Raymond was an athlete whom I knew well and who had become a friend. He was the only person I knew personally who had actually competed on a US national team and on the professional international circuit. After practice he invited me over to his apartment. When I got there he was still unpacking his bags. He had become a Nike-supported athlete, which meant that since he wasn’t a professional athlete yet they couldn’t pay him but they could send him all the shoes and gear he wanted. He had bags of new Nike gear and USA team gear. He had picked up gifts that were given to him at the international competitions he had taken part in. There were CD players too, which in 1987 was a new technology and a very cool thing to have.

My eyes opened as wide as the Olympic medals I would eventually earn. I couldn’t believe all of the free gear and gifts he had received. And he had actually had the experience of competing on a US team and the international circuit, which he told me all about. I wanted that experience myself. To top all of that off, a week later Raymond drove up to practise in a really cool new red scooter. Those had become really popular in the US then, and he had been able to buy it with the expense money he received from his trip to Europe. I was hooked and needless to say inspired. I asked Raymond questions for weeks after his return, and he was happy to share every detail of his trip and experience with me.

Unlike me, some Olympian champions caught Olympic fever early on. ‘That’s what I want to do in life,’ Sally Gunnell realised at the age of 14 as she sat glued to the television during the Moscow Olympics watching anything that moved. Entranced with Nadia Comaneci and Olga Korbut, she decided to join a gymnastic club. Only after another girl at her school announced that she was going down to athletics did Sally decide to go along. ‘I thought it would be better to go with somebody rather than go on my own,’ she recalls. So she joined the athletics club and went on to win a gold medal in the 400 metres hurdles at the 1992 Olympics.

Steve Redgrave found success so early in his rowing career that he simply assumed winning the Olympics was inevitable. ‘The first year, we thought we were brilliant,’ he says. After just messing around in the water, the team had entered their first race for fun and actually won. The following season they entered seven events and won all seven. ‘We were God’s gift to rowing,’ he said. By the time Steve was 15 people had begun to tell him, ‘You’re really good at this. One day you could be a world champion.’

‘I thought, “World champion sounds nice; why not Olympic champion?” I knew I wanted to be an Olympian, because I was the best in the country. Why not?’

That sense of inevitability would prove to be both his great motivation and, initially, his downfall. ‘I figured, “All I’ve got to do is follow what the coaches are telling me to do and it will happen,”’ he recalls. ‘It wasn’t until 1983 when I went to the senior world championships as a single sculler and I got eliminated – I didn’t make the top 12 – that I suddenly thought, “I am good domestically, I’m okay internationally, but not the same sort of level as people are saying I am good at.” Suddenly it dawned on me that if you have an ability you’ve got to bring that ability out. It’s about how hard and how well you prepare. That was the turning point in my career.’ It would also prove to be the turning point in his life, transforming him from ‘shy goose’ to confident five-time gold medallist.

RUNNING INTO THE RECORD BOOKS

Jackie Joyner-Kersee, the Greatest Female Athlete of the 20th Century according to Sports Illustrated for Women magazine, was the opposite of shy from the very beginning. ‘I was very outgoing,’ she told me. ‘I was one who would put my phone number down and have people contact me, and my mom would have to tell me, “You stop putting your number down on everything, because I’m tired of all these strangers calling the house.” Because I wanted to be involved in everything.’

Jackie, three-time Olympic gold medal winner who would become one of the all-time greats in women’s heptathlon and long jump, thought she was good at track and field from the moment she and her sister signed up at the community centre. She had long legs and could jump high. Of course she was good, the nine-year-old reasoned. ‘My first race, I finished last,’ she told me. ‘That challenged me to really continue to run. Then some of my friends made the relay team. I wanted to be on the relay team but I was number six or seven. So I just set my sights on trying to improve a tenth of a second if I was running or half an inch if I was jumping. That was to let me know I was getting better, that the work I was doing was paying off.

‘I didn’t really know what a track looked like, because we ran in a park, and we ran on cinder. This park had just one big dirt track around. The coaches told us it was about 400 metres, but as we got older we realised it was like 1,200. When you’re younger they can pull that stuff on you. I could never finish the lap, and I was like, wow! So the goal was to try to go one lap around without stopping. All this started at the age of nine. It wasn’t until I was 14 when I saw the 1976 Olympic Games on television that I saw girls doing what I was trying to do. That’s the first time I ever saw girls or women on TV doing sports. I thought, “Maybe I will go to the Olympics one day.”

‘It was really the idea of being on television that most attracted me. For real! I had to get on TV and it seemed like everyone was talking about the Olympics. Our coaches told us to watch. I saw sprinter Evelyn Ashford [win gold]. I saw Nadia Comaneci who was the same age as me earn a perfect score. At that time I was like, “I’m going to be a gymnast, too.”’

The gymnast fantasy came and went, but Jackie’s dedication to track and field held firm. Although Jackie didn’t know if she could ever be good enough to get to the Olympics, even imagining the possibility motivated her. Besides, hanging out at the community centre and doing sports got her away from home, which she found hugely appealing. Mostly, however, she just wanted to see whether hard work would continue to yield progress. ‘I practised hard, and the results were coming. It took me a while to get out of last place and then sixth place, but the placement didn’t matter to me because I saw my times improving.’

It didn’t take long for people to start recognising Jackie’s potential. ‘People would say, “You’re gifted. You’re talented.” But I really didn’t know what all that meant. I was kind of rough in those days. I would fight another girl because she was seeing my friend’s boyfriend – all kinds of crazy stuff that would get me into trouble. One day the Assistant Principal pulled me off a girl I was fighting and said, “Get up to my office.” When he got there he told me, “You know, we expect better things out of you.” I’ll never forget that. It was like, wow, people see some greatness in me.’

That helped Jackie decide to commit to her training in a serious way. ‘I remember telling my girlfriends when I was in junior high school that I was going to go to the Olympics. They thought I was crazy. From that day on I said to my friends, “No, I can’t meet with y’all.” We were basically a gang, and I just knew that wasn’t good.’

As luck would have it, her school started complying with Title IX, legislation guaranteeing girls the same access to sports as boys, which had been enacted four years earlier, just in the nick of time for Jackie. ‘My first year in high school, which would have been my sophomore year, we couldn’t practise until 6:30 p.m. after the boys finished their practice. My mom, who was really strict, wasn’t going for that. I’m going to come home and then go back up to the school and practise? She wasn’t feeling that at all. My mom was just going to pull me out of sports altogether because her philosophy was that I had to be home before the streetlights came on. Then the coaches started pushing the Title IX issue because they said that wasn’t right. From there, they changed it so that we could practise before the boys. That made a big difference.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.