Полная версия

Food for Free

Tilleul

Gather the flowers whilst they are in full bloom, in June or early July, and lay them out on trays or sheets of paper in a warm, well-ventilated room to dry. After two or three weeks they should have turned brittle and will be ready for use. Make tea from them in the usual way, experimenting with strengths, and serve like China tea, without milk.

Sloe, Blackthorn Prunus spinosa

Widespread and abundant in woods and hedgerows throughout the British Isles, though thinning out in the north of Scotland. A stiff, dense shrub, up to 6 m (20 ft) high, with long thorns and oval leaves. The flowers are small and pure white and appear before the leaves. The fruit is a small, round, very dark blue berry covered when young with a paler bloom.

The sloe is one of the ancestors of cultivated plums. Crossed with the cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera), selected, crossed again, it eventually produced fruits as sweet and sumptuous as the Victoria plum. Yet the wild sloe is the tartest, most acid berry you will ever taste. Just one cautious bite into the green flesh will make the whole of the inside of your mouth creep. But a barrowload of sloe-stones was collected during the excavation of a Neolithic lake village at Glastonbury. Were they just used for dyeing? Or did our ancestors have hardier palates than us? For all its potent acidity, the sloe is very far from being a useless fruit. It makes a clear, sprightly jelly, and that most agreeable of liqueurs, sloe gin.

Sloe gin

The best time to pick sloes for this drink is immediately after the first frost, which makes the skins softer and more permeable. Sloe gin made at this time will, providentially, just be ready in time for Christmas. Pick about a pound of the marble-sized berries (you will probably need a glove as the spines are stiff and sharp). If they have not been through a frost, pierce the skin of each one with a skewer, to help the gin and the juices get together more easily. Mix the sloes with a quarter of their weight of sugar, and half fill the bottles with this mixture. Pour gin into the bottles until they are nearly full, and seal tightly. Store for at least two months, and shake occasionally to help dissolve and disperse the sugar. The result is a brilliant, deep pink liqueur, sour-sweet and refreshing to taste, and demonstrably potent. Don’t forget to eat the berries from the bottle, which will have quite lost their bitter edge, and soaked up a fair amount of the gin themselves. And try dipping the drunken sloes in molten chocolate first. As an alternative, try replacing the gin in the recipe above with brandy or aquavit.

© Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA

© Bob Gibbons/FLPA

© A.N.T. Photo Library

Wild Cherry Prunus avium

Widespread and frequent in hedgerows and woods, especially beech. A lofty tree, up to 30 m (100 ft) high, with shining, reddish-brown bark and an abundance of five-petalled white flowers in the spring. Leaves are alter-nate, oval, sharply toothed. The fruit is like a small, dark or light red, cultivated cherry.

The wild cherry is a beautiful tree in the springtime, and again in autumn when the leaves turn red. The fruit can be either sweet or bitter. It used to be sold occasionally in London on the branch. These are the best fruits to use for cherry brandy. Put as many as you can find in a bottle with a couple of teaspoons of sugar, and top up with brandy. It will be ready after three or four months. Another wild cherry product is the sticky resin that exudes from the trunks, especially if they’re damaged in some way. This has been used by children and forestry workers as a kind of chewing gum. It has, like most gums, more texture than taste.

© John Eveson/FLPA

Bullace, Damsons and Wild Plums Prunus species

The true bullace, Prunus domestica ssp. insititia, may be a scarce native of old hedgerows, but the majority of wild plums found in the countryside are either seeded from garden trees or are reverted orchard specimens. Fruit blue-black, brownish, or green-yellow, and usually midway in size between a sloe and a cultivated damson.

Wild plums are ripe from early October, and, unlike sloes, are usually just about sweet enough to eat raw. Otherwise they can be used like sloes, in jellies, gin, and autumn puddings. Wild plums make excellent dark jams, and the French jam specialist Gisèle Tronche has pointed out how the addition of a little ground cumin seed and aniseed can improve conventional recipes. Alternatively try her late autumn, wild fruit humeur noir, which she describes as having ‘the colour of a good, healthy, black-tempered funk’.

Wild fruit jam

Crush together 800 g (2 lb) of stoned dark damsons and 200 g (8 oz) sugar, and leave overnight. Boil together 200 g (8 oz) of elderberries and 600 g (1½ lb) of blackberries for ten minutes. Add the damsons, another 600 g (1½ lb) of sugar, a tablespoon of cider vinegar and the juice of one lemon, and bring to the boil again. Cook for about an hour, until the desired consistency is reached. Pour into jars, leave to cool, and then seal.

Lamb and plum tagine

2 medium onions

50 g (2 oz) butter

1 tsp cumin seed

1 tbsp finely chopped root ginger

a few threads of saffron

3 cloves of garlic

1 tsp cinnamon

1 kg (2 lbs) organic lamb, shanks or small leg

500 g (1 lb) wild cherry plums, or damsons

water, stock or white wine

sloe or damson gin (optional)

In a casserole or thick saucepan, sauté the onions in the butter with the cumin seed, for about 10 minutes, until the seeds have burst and the onions are golden. Add the ginger, saffron, crushed garlic and cinnamon. Cook together for a couple of minutes. Fry the lamb in the mixture quickly, turning it so that all sides are slightly browned and well coated with the spices. Add half the damsons, and about a cupful of water, stock or white wine. Cook gently in an oven at 150°C/gas 2, for 2 hours, checking the level of the liquid once or twice. Fifteen minutes before the end, add the remainder of the damsons and a small glass of sloe or damson gin – if you enjoy the almond taste given by plum-family stones. The liquid should be appreciably thicker at the end (give it a sharp boil for 5 minutes on top of the stove if not), and the lamb coming free of the bone.

Crab Apple Malus sylvestris

A small deciduous tree, frequent in woods, heath and hedges. Leaves are oval and often downy. White or pink blossom appears April – May, and a yellowish-green fruit from July.

Most of the apples growing wild in the countryside are not true crab apples, but what are known as ‘wildings’ – that is, apples that have sprung naturally from the discarded cores of cultivated varieties. Apple varieties and species cross-fertilise very readily: this is why apple trees must be propagated by grafting if they are to stay true, and why it has been possible, over the last few centuries, for breeders to raise more than 6,000 named varieties. So don’t despise wilding apples. They are often sweet enough to eat raw, and here and there, for instance, in a hedge by an old orchard, you may find a descendant of an obsolete variety such as Margil, which still has some of its parents’ characteristics. True crab apples, which tend to be confined to old hedges and open woods, are best used for tart jellies and for pickling. They can be identified by their spiny branches, and by the smaller, harder and greener fruit. Use them not only by themselves, but mixed with other wild fruits for jellies or ‘hedgerow jam’; blackberry, elderberry, wild plums and hazelnuts are good companions. Alternatively, pickle the apples, unpeeled, in spiced vinegar as an accompaniment to roast pork. Thrown in the pan with the meat, they will burst and baste it with their juices.

Uncooked apple and pear chutney

This is a recipe developed by my brother David from an Australian version, which in turn seems to have originated in the East End of London, to judge from its rhyming-slang nickname ‘Stairs Pickle’. It’s unusual in being uncooked.

450 g (1 lb) sharp apples

450 g (1 lb) firm pears

25 g (1 oz) root ginger

2 cloves of garlic

450 g (1 lb) raisins

450 g (1 lb) white sugar

600 ml (1 pint) cider vinegar

2 tsp of salt

1 tsp chilli powder

Peel and core the apples and pears, and finely chop the root ginger and garlic. Mix them thoroughly with all the other ingredients, cover and leave in a cool, dark place for 3 days. Bottle the chutney in sterilised jars. It will be ready to use in about a month.

© David Hosking/FLPA

© David Hosking/FLPA

Apple cheese

Crab apples may be used to make an apple cheese, though wilding apples may produce an even better result. Wash, core and roughly chop about 900 g (2 lbs) of fruit, and simmer in 300 ml (½ pint) of water. Once the fruit is soft, purée by pressing through a sieve. Add 450 g (1 lb) brown sugar to each pound of purée, and pinches of cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and cloves, bring to the boil and simmer until very thick. Bottle in the usual way. When cool it should have the consistency of a soft cheese.

Apple mash

potatoes

cooking apples

butter

seasoning

Use potatoes and apples in the proportions of two to one by weight. Peel and halve the potatoes and bring to the boil. After about 10 minutes add the peeled, cored and chopped apples. They’ll both be cooked in another 10 minutes. Drain, return to the saucepan, add a few slivers of butter and some salt and pepper, and pound with a masher or fork. Do not add any extra milk, cream or oil, as there is plenty of liquid produced by the apples.

Jugged celery and windfalls

This is a wonderful old country recipe, gathered by Dorothy Hartley. It can be used as either a starter or a vegetable with pork or lamb.

For 2 people

equal weight of windfall apples and celery, say 250 g (½ lb) each

2 cloves

muscovado sugar

4 rashers of bacon or ham

Wash and trim the apples, but leave their skins on. Chop roughly and stew them with a couple of cloves and a spoonful of muscovado sugar in as little water as possible, until they are a firm pulp. Put a couple of slices of bacon in the bottom of the tallest, narrowest cooking pot you possess, pile the apple purée on top, then pack in as many sticks of celery as you can. They must be in an upright position, as it is the apple juices running down the fibres of the celery that makes this dish. Spoon out any apple purée that overflows, trim the sticks level and cover their tops with 2 more bacon rashers, cut to fit. Then bake in an oven at about 180°C/gas 4 for half an hour. If you don’t have a suitable tall cooking jug, an ordinary casserole dish will do.

Rowan, Mountain-ash Sorbus aucuparia

Widespread and common in dry woods and rocky places, especially on acid soils in the north and west of the British Isles. A small tree, up to 20 m (65 ft), with fairly smooth grey bark, toothed pinnate leaves, and umbels of small white flowers. Fruit: large clusters of small orange or red berries, August to November.

The rowan is a favourite municipal tree, and is planted in great numbers along the edges of residential highways, but you should not have too much trouble finding wild specimens. Their clusters of brilliant orange fruits are unmistakable in almost every setting, against grey limestone in the uplands, or the deep evergreen of Scots pine on wintry heaths. Unless the birds have got there first, rowan berries can hang on the trees until January. They are best picked in October, when they have their full colour but have not yet become mushy.

You should cut the clusters whole from the trees, trim off any excess stalk, and then make a jelly in the usual way, with the addition of a little chopped apple to provide the pectin. The jelly is a deliciously dark orange, with a sharp, marmaladish flavour, and is perfect with game and lamb.

© Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA

© Derek Middleton/FLPA

Wild Service-tree Sorbus torminalis

A relative of the rowan and the whitebeam, largely confined to ancient woods and hedgerows on limestone soils in the west and stiff clays in the Midlands and south. Up to 25 m (80 ft). Leaves are alternate, deeply toothed, in pairs. Flowers are white branched clusters, May to June. Fruit is brown and speckled, 12–18 mm (½–¾ inch).

The wild service-tree is one of the most local and retiring of our native trees, and knowledge of the fascinating history of its fruits has only recently been rediscovered.

The fruits, which appear in September, are round or pear-shaped and the size of small cherries. They are hard and bitter at first, but as autumn progresses they ‘blet’ – or go rotten – and become very sweet. The taste is unlike anything else which grows wild in this country, with hints of damson, prune, apricot, sultana and tamarind.

Remains of the berries have been found in prehistoric sites, and they must have been a boon before other sources of sugar were available. In areas where the tree was relatively widespread (e.g. the Weald of Kent) they continued to be a popular dessert fruit up to the beginning of the twentieth century. The fruits were gathered before they had bletted and strung up in clusters around a stick, which was hung up indoors, often by the hearth. They were picked off and eaten as they ripened, like sweets.

The tree is also known as the chequer tree, referring to the traditional pub name Chequers (the chequerboard was the symbol for an inn or tavern in Roman times). The berries were used quite extensively in brewing.

Chequerberry beer

I have the house recipe for ‘chequerberry beer’ from the Chequers Inn at Smarden, Kent. ‘Pick off in bunches in October. Hang on a string like onions (look like swarm of bees). Hang till ripe. Cut off close to berries. Put them in stone or glass jars. Put sugar on – 1 lb to 5 lb of berries. Shake up well. Keep airtight until juice comes to the top. The longer kept the better. Can add brandy. Drink. Then eat berries!’

© Derek Middleton/FLPA

Whitebeam Sorbus aria

Locally frequent in scrub and copses in the south of England, and popular as a suburban roadside tree. Also a very striking shrub, flashed with silver when the wind turns up the pale undersides of the leaves.

The bunched red berries are edible as soon as they begin to ‘blet’, like service berries. In the seventeenth century John Evelyn recommended them in a concoction with new wine and honey, though they are rather disappointing.

© Bob Gibbons/FLPA

Juneberry Amelanchier lamarckii

An American shrub naturalised in woodlands in a few areas of the south of England, notably on sandy soils in Sussex. Up to 10 m (33 ft) high. Leaves alternate, oblong. Drifts of white blossom in April and May. Fruit purplish-red/black, 10 mm (½ inch) with withered sepals, in June.

The purplish-red berries rarely form in this country, but they are sweet to taste, and can be eaten uncooked or made into pies. In America they are sometimes canned for winter use.

Medlar Mespilus germanica

A small, twisted deciduous tree, with long, untoothed and downy leaves. Large solitary white flowers appear in May. Fruits resemble large brown haws.

Medlar was, together with quince, mulberry and walnut, one of the quartet of trees that were usually planted singly in old herb gardens, often at the corners. They are now largely out of fashion in cultivation, and are probably not native in Britain. Yet the odd tree can still be found in old parkland and orchards, and, in the south of England, in hedgerows and woods near farms. These may be bird-sown, naturalised specimens; but fruit trees were occasionally planted out in these sites so as not to take up cultivated ground. Medlars are remarkable for their dark contorted trunks, their solitary white flowers which sit on the trees like camellias, and for the large brown fruits that start to fall from the tree in November. Although they were once recommended as a treatment for diarrhoea, they are wood-hard in this state and must be allowed to ‘blet’, or decay, before they are edible. Kept in a warm, dry place for a couple of weeks, the flesh browns, sweetens and softens to a consistency something like that of chestnut purée.

Medlar comfit

The bletted fruits make an intriguing confection served as they are. The slightly ‘high’, fruity flavour and granular texture make them ideal for serving with whisky. The flesh can easily be squeezed out of one end of the fruits if they are properly ripe. Alternatively, the tops can be cut off and the flesh scooped out with a spoon, then topped with cream and brown sugar to taste.

Medlar purée

Medlar purée makes a good filling for a flan or pie. Make a pulp by mixing three parts of medlar pulped through a sieve, one part double cream, a little sugar and the juice of two lemons, all whipped together until smooth.

© Derek Middleton/FLPA

© Roger Tidman/FLPA

Hawthorn, May-tree Crataegus monogyna

Widespread and abundant on heaths, downs, hedges, scrubland, light woods and all open land. Small tree or large shrub, up to 6 m (20 ft) high. Leaves glossy green and deeply lobed on spiny branches. Flowers: May to June, abundant umbels of white (sometimes pink) strongly scented blossoms. Fruit: small round dark red berries, in bunches.

The young April leaves – traditionally called bread and cheese by children in England – have a pleasantly nutty taste. Eat them straight from the tree or use them in sandwiches, or in any of the recipes for wild spring greens. They also blend well with potatoes and almost any kind of nuts. A sauce for spring lamb can be made by chopping the leaves with other early wild greens, such as garlic mustard and sorrel, and dressing with vinegar and brown sugar, as with a mint sauce. The leaf buds can be picked much earlier in the year, though it takes an age to gather any quantity, and they tend to fall apart. Dorothy Hartley has a splendid recipe for a spring pudding which makes use of the buds, for those with the patience to collect large numbers of them.

Hawthorn berries (haws) are perhaps the most abundant berry of all in the autumn. Almost every hawthorn bush is festooned with small bunches of the round, dark-red berries, looking rather like spherical rosehips. When fully ripe they taste a little like avocado pear. They make a moderate jelly, but being a dry fruit need long simmering with a few crab apples to bring out all the juices and provide the necessary pectin. Otherwise the jelly will be sticky or rubbery. It is a good accompaniment to cream cheese.

Hawthorn spring pudding (Dorothy Hartley)

Make a light suet crust, well seasoned, and roll it out thinly and as long in shape as possible. Cover the surface with the young leaf-buds, and push them slightly into the suet. Take some rashers of bacon, cut into fine strips and lay them across the leaves. Moisten the edges of the dough and roll it up tightly, sealing the edges as you go. Tie in a cloth and steam for at least an hour. Cut it in thick slices like a Swiss roll, and serve with gravy.

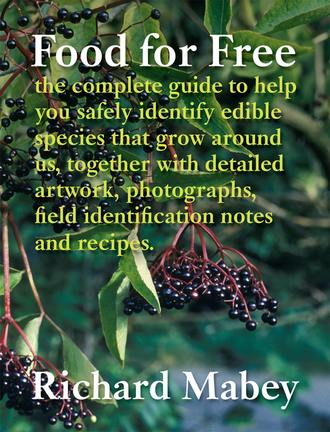

Elder Sambucus nigra

Widespread and common in woods, hedgerows and waste places. A tall, fast-growing shrub, up to 10 m (33 ft), with a corky bark, white pith in the heart of the branches, and a scaly surface to the young twigs. Leaves usually in groups of five; large, dark green and slightly toothed. Flowers are umbels of numerous tiny creamy-white flowers, June to July. Fruits are clusters of small, reddish-black berries, August to October.

To see the mangy, decaying skeletons of elders in the winter you would not think the bush was any use to man or beast. Nor would the acrid stench of the young leaves in spring change your opinion. But by the end of June the whole shrub is covered with great sprays of sweet-smelling flowers, for which there are probably more uses than any other single species of blossom. Even in orthodox medicine they have an acknowledged role as an ingredient in skin ointments and eye-lotions.

Elderflowers can be munched straight off the branch on a hot summer’s day, and taste as frothy as a glass of ice-cream soda. Something even closer to that drink can be made by putting a bunch of elderflowers in a jug with boiling water, straining the liquid off when cool, and sweetening. Cut the elderflower clusters whole, with about 5 cm (2 inches) of stem attached to them. Always check that they are free of insects, and discard any that are badly infested. The odd grub or two can be removed by hand. But never wash the flowers, as this will remove much of the fragrance. The young buds can be pickled or added to salads. The flowers themselves, separated from the stalks, make what is indisputably the best sparkling wine besides champagne. One of the most famous recipes for elderflowers is the preserve they make with gooseberries.