Полная версия

Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse

(Like Pieter, Julie and Bess also make an appearance of sorts in A Medal for Leroy.)

It was Bess who was deputed to take Pieter and Michael for a walk one afternoon, and to explain to them that Jack was now their father. A memory of their conversation remains with Michael, fragmentary but crystal-clear. ‘We were on a railway bridge. I must have said something about my father, and Bess said, “Well, you’ve got a new father now, you know.” And a train came by, and the steam came up in my face. And it just felt quite strange.’

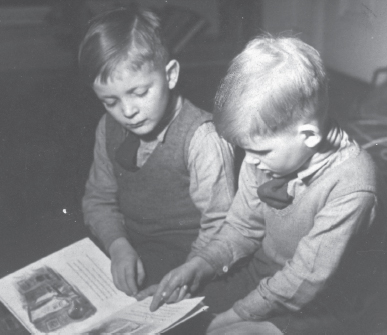

Michael and Pieter outside 84 Philbeach Gardens.

At this time Michael was a robust, sunny toddler, and had a close bond with his mother. He remembers walking with her, hand-in-hand, through the smog that descended on London like a manifestation of post-war gloom. He remembers the thrill of being allowed to take charge of the ration book when they shopped together at the local International Stores, where he committed his first crime, slipping into his pocket a model Norman soldier with an orange tunic and an irresistible hinged helmet. He remembers stopping with her to talk to the weepy-eyed, skewbald milk-cart horse, Trumpeter, which used to stand shifting from foot to foot in Philbeach Gardens, munching from the sack of hay round his neck, giving off what seemed to Michael a fascinating odour of fur and sweat and dung. That interest in animals would remain a constant throughout Michael’s life, and would surface again and again in his novels.

Pieter and Michael, 1948.

But most vivid of all are his memories of bedtime, when Kippe would sit at the end of his bed and read to him. She read from Aesop’s Fables, and from poets such as Masefield and de la Mare, from Belloc, Lear and from Kipling’s Just So Stories. She had a way of making imaginary characters and places come alive, of conveying the music and joy and taste of language:

Then Kolokolo Bird said, with a mournful cry, ‘Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees …’

Michael rolled the words around on his tongue like sweets. When he was three, his mother found him rocking to and fro in his bed, chanting, ‘Zanzibar! Zanzibar! Marzipan! Zanzibar!’

Story-time over, Kippe would leave the door slightly ajar to let in a chink of light. The smell of her face powder lingered in the room.

Sometimes there could be about Kippe an almost reckless joyfulness. When one afternoon Pieter and Michael locked themselves into their fifth-floor bedroom while they were supposed to be resting, she shinned undaunted up a drainpipe, ignoring Jack’s protests, and climbed in through their window to rescue them. When visitors came to the house she shone. ‘As she opened the front door,’ Michael remembers, ‘it was as if she was walking on to a stage – beautifully dressed and made-up, charming, sparkling.’

But when the visitors left she tended to collapse, reaching for her cigarettes and smoking almost obsessively. And sometimes for days on end a sadness – what Pieter calls ‘a wondering’ – would settle upon her, and she became quiet and unreachable. Twice a year she would take Pieter and Michael on a bus to Twickenham to visit Tony’s parents in their neat, modest, semi-detached house in Poulett Gardens. Michael remembers the uncomfortable formality of these visits – ‘the scones, the clinking of spoons on teacups’ – and the awkwardness as the conversation turned to Tony, his grandparents bringing out photographs and press clippings to show to the boys. On the way home, and for days afterwards, Kippe was silent. Michael knew that to ask questions would upset her further, so he too remained silent, aware simply that ‘ours was a family which had at its heart a tension’.

In the wider world, too, he was becoming aware of complexity and shadows. The area around Philbeach Gardens had been heavily bombed in the Blitz, and the house next to number 84 completely destroyed. The cordoned-off bomb site was reachable via the cellar, and Michael particularly liked to play here alone. ‘It was my Wendy house, I suppose. A rather tragic Wendy house.’ Among the weeds and crumbling walls were remnants of life – bits of cutlery, a chair, an iron bedstead – evidence that in the very recent past ‘there had been this terrible trauma’ for the family that had lived there.

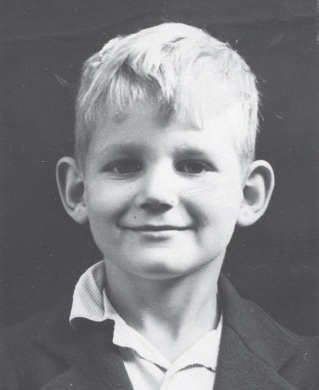

Michael, 1948.

School, when it came, confirmed his sense that the world could be harsh. At three, Michael was taken to a playgroup in the hall of St Cuthbert’s, Philbeach Gardens: a cosy, eccentric set-up, where the lady in charge kept order by issuing the children with linoleum ‘islands’ on which they would be asked to sit if they threatened to become unruly. At five, he moved on to the local state primary school, St Matthias, across Warwick Road. It seemed a cavernous, grim place to a small boy, with painted brick walls as in a prison or hospital, and windows so high that if a child tried to look out all he could see were small segments of sky.

There was one magical element. Beneath the school lived a community of refugee Greek Orthodox monks: long, black-robed creatures who glided soundlessly in and out of a dark chapel full of glowing lanterns. But within the school itself the children were coaxed into learning through fear. Mistakes were met with a thwack of the teacher’s ruler, either on the palm of the hand, or, more painfully, across the knuckles. Michael found himself frequently standing in the corner. Books and stories were suddenly filled with menace – ‘words were to be spelt, forming sentences and clauses, with punctuation, in neat handwriting and without blotches’. He developed a stutter, his tongue and throat clamping with terror when he was asked to read or recite to the class; and he began to cheat, squinting across to copy from brainy Belinda, who shared his double desk, and with whom he was in love.

So it came as a relief when, just after his seventh birthday, plans were made for Michael to leave St Matthias and join Pieter at his prep school in Sussex. Kippe took him on a bus to Selfridges, and he remembers the delight of being measured up, of being the centre of attention, of watching his ‘amazing’ uniform (green, red and white cap; blazer ‘like the coat of many colours’; rugby boots; shiny, black, lace-up shoes; socks; shorts; shirts and ties) piling up on the counter – ‘all for me!’ He had remained, despite everything, a happy child, ‘very positive, full of laughs, a bit of a show-off’, and the prospect of prep school was thrilling. ‘I was really looking forward to it,’ he says. ‘I had no idea what was in store.’

It can be uncomfortable when family stories believed to be true are revealed as myth. When Maggie told me the truth about my uncle Pieter’s death, it took a while to sink in. The story I’d believed for nearly seventy years had entered deeply into my imagination. I wanted to work Uncle Pieter into a story. And I set it at number 84 Philbeach Gardens.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.