Полная версия

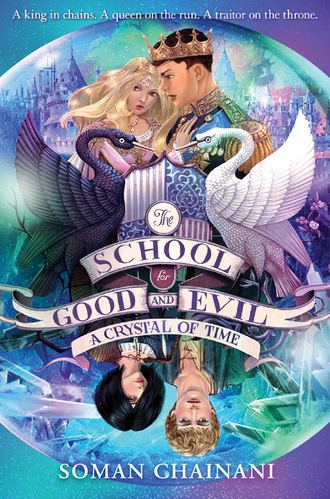

A Crystal of Time

He’d been a bad king. Cowardly. Arrogant. Foolish.

When Agatha had told Sophie this last night, he’d been cut to the bone. Betrayed by the only girl he’d ever loved. It had made him doubt her the way she doubted him.

But in the end, she was right. She always was.

And now, in the most fitting of ironies, the same girl who called him a bad king was the sole person who could help him win back his throne.

Because Agatha was the only one who’d managed to escape Rhian’s hands.

The pirates had revealed this by accident. They’d beaten him relentlessly, the gang of six reeking thugs, demanding to know where Agatha had fled. At first, his relief that she’d escaped numbed the pain of their blows. But then the relief wore off. Where was she? Was she safe? Suppose they found her? Riled by his silence, the pirates had only beaten him harder.

Tedros leaned against the dungeon wall, warm blood sliding down his abdomen. His raw, bruised back touched cold stone through the shreds in his shirt and he seized up. The throbbing was so intense his teeth chattered; he tasted a sharp edge in the bottom row where one of them had been chipped. He tried to think of Agatha’s face to keep him conscious, but all he could conjure were the faces of those filthy punks as their boots bashed down. The pirates’ assault had gone on for so long that at some point, it seemed disconnected from purpose. As if they were punishing him for his very existence.

Maybe Rhian had built his whole army on feelings like this. Feelings of people who thought because Tedros was born handsome and rich and a prince, he deserved to fall. To suffer.

But he could take all the suffering in the world if it meant Agatha would live.

To survive, his princess had to run as far as she could from Camelot. She had to hide in the darkest part of the Woods where no one could find her.

But that wasn’t Agatha. He knew her too well. She would come for her prince. No matter how much faith she’d lost in him.

The dungeons were quiet now, Rhian’s voice no longer audible.

“How do we get out of here!” Tedros called to the others, enduring blinding pain in his rib. “How do we escape!”

No one in their cell responded.

“Listen to me!” he shouted.

But the strain had done him in. His mind softened like soggy pudding, unlocking from his surroundings. He pulled his knees into his chest, trying to relieve pressure on his rib, but his flank burned hotter, the scene distorting in the torch-haze on the wall. Tedros closed his eyes, heaving deep breaths. Only it made him feel more sealed in, like he was in an airless coffin. He could smell the old bones . . . “Unbury Me,” his father’s voice whispered. . . .

Tedros wrenched out of his trance and opened his eyes—

Hester’s demon stared back at him.

Tedros recoiled against the wall, blinking to make sure it was actually there.

The demon was the size of a shoebox with brick-red skin and long, curved horns, his beady eyes locked on the young prince.

The last time Tedros had been this close to Hester’s demon, it had almost hacked him to pieces during a Trial by Tale.

“We thought this would work better than yelling across the dungeon,” said the demon.

Only it didn’t speak in a demon’s voice.

It spoke in Hester’s.

Tedros stared at it. “Magic is impossible down here—”

“My demon isn’t magic. My demon is me,” said Hester’s voice. “We need to talk before the pirates come back.”

“Agatha’s out there all on her own and you want to talk?” Tedros said, clutching his rib. “Use your little beast to get me out of this cell!”

“Good plan,” the demon retorted, only with Beatrix’s voice. “You’d still be trapped at the iron door and when the pirates see you, they’ll beat you worse than they already have.”

“Tedros, did they break any bones?” Professor Dovey’s voice called faintly through the demon, as if the Dean was too far from it for a proper connection. “Hester, can you see through your demon? How bad does he look—”

“Not bad enough, whatever it is,” Hort’s voice said, hijacking the demon. “He got us into this mess by fawning over Rhian like a lovedrunk girl.”

“Oh, so being a ‘girl’ is an insult now?” Nicola’s voice ripped, the demon suddenly looking animated in agreement.

“Look, if you’re going to be my girlfriend, you have to accept I’m not some intellectual who always knows the right words to use,” Hort’s voice rebuffed.

“YOU’RE A HISTORY PROFESSOR!” Nicola’s voice slapped.

“Whatever,” Hort barged on. “You saw the way Tedros gave Rhian the run of his kingdom, letting him recruit the army and give speeches like he was king.”

Tedros sat up queasily. “First of all, how is everyone talking through this thing, and second of all, do you think I knew what Rhian was planning?”

“To answer the first, Hester’s demon is a gateway to her soul. And her soul recognizes her friends,” the demon said with Anadil’s voice. “Unlike your sword.”

“And to answer the second, every boy you like ends up a bogey,” Hort’s voice jumped in, the demon trying to keep up like a ventriloquist. “First you were friends with Aric. Then you were friends with Filip. And now you canoodled with the devil himself!”

“I did not canoodle with anyone!” Tedros yelled at the demon. “And if any of us is cozying up to the devil, you’re the one who’s friends with Sophie!”

“Yeah, Sophie, the only person who can rescue us!” Hort’s voice heckled.

“Agatha’s the only person who can rescue us, you twit!” Tedros fired. “That’s why we need to get out now, before she comes back and gets captured!”

“Can everyone shut up?” the demon snapped in Hester’s voice. “Tedros, we need you to—”

“Put Hort back on,” Tedros demanded. “After three years of Sophie using you as her personal bootlicker without giving you the slightest in return, now you think she’s going to rescue us!”

“Just because you wouldn’t help people who needed it when the Snake attacked doesn’t mean she won’t,” Hort’s voice thrashed.

“Idiot. Once she tastes a queen’s life, she’ll let us burn while she feasts on cake,” Tedros slammed.

“Sophie doesn’t eat cake,” Hort sniffed.

“You think you know Sophie better than me?”

“When she rescues you from that cell, you’re going to feel like a boob—”

“ANI’S RAT IS DEAD, THE SNAKE IS ALIVE, WE’RE IN A DUNGEON, AND WE’RE TALKING ABOUT SOPHIE! AND CAKE!” Hester’s voice boomed, her demon swelling like a balloon. “WE HAVE QUESTIONS FOR TEDROS, YES? GIVEN WHAT WE SAW ONSTAGE, OUR LIVES DEPEND ON THESE QUESTIONS, YES? SO IF ANYONE EVEN TRIES TO INTERRUPT ME, STARTING RIGHT NOW I’LL TEAR OUT YOUR TONGUE.”

The dungeon went silent.

“The Snake is alive?” Tedros asked, ghost-faced.

Ten minutes later, Tedros stared back at the red imp, having learned about the Snake’s reappearance, the birth of Lionsmane, and everything else Hester and the team had seen in the magical projection they’d conjured in their cell.

“So there’s two of them? Rhian and this . . . Jasper?” Tedros said.

“Japeth. The Snake. And that’s how we think they tricked both the Lady and Excalibur. They’re twins who share the same blood. The blood of your father, they say,” the demon explained. “If we’re going to bring them down, we need to know how that’s possible.”

“You’re asking me?” Tedros snorted.

“Do you live your whole life with your head up your bum?” Hester’s voice scorned. “Think, Tedros. Don’t shut down what might be possible just because you don’t like the idea of it. Can these two boys be your brothers?”

Tedros scowled. “My father had his faults. But he couldn’t have bred two monsters. Good can’t spawn Evil. Not like that. Besides, how do you know Rhian didn’t pull Excalibur because I’d done all the work dislodging it? Maybe he just got lucky.”

The demon groaned. “It’s like trying to reason with a hedgehog.”

“Oh, just let him die. If they are his brothers, it’ll be survival of the fittest,” said Anadil’s voice. “Can’t argue with nature.”

“Speaking of nature, I have to use the toilet,” said Dot’s voice.

Professor Dovey’s voice muffled something to Tedros through the demon, something about his father’s “women”—

“I can’t hear you,” said Tedros, cramming deeper into a corner. “My body hurts, my head hurts. Are we done with the interrogation?”

“Are you done being a pea-brained fool?” Hester railed. “We’re trying to help you!”

“By making me smear my own father?” Tedros challenged.

“Everyone needs to cool their milk,” said Nicola’s voice.

“Milk?” Kiko’s voice peeped through the demon. “I see no milk.”

“It’s what my father used to say at his pub when it got too hot in the kitchen,” said Nicola, calmly taking over the creature. “Tedros, what we’re trying to ask is whether there’s anything you can tell us about your father’s past that makes Rhian and his brother’s claim possible. Could your father have had other children? Without you knowing? We get that it’s a difficult subject. We just want to keep you alive. And to do that, we need to know as much as you do.”

There was something about the first year’s voice, so lacking in pretense, that made Tedros let down his guard. Maybe it was because he barely knew the girl or that there was no judgment or conclusion in her question. All she was asking was for him to share the facts. He thought of Merlin, who often spoke to him the same way. Merlin, who was either in danger somewhere up there or . . . dead. Tedros’ gut knotted. The wizard would have wanted him to answer Nicola honestly. Indeed, Merlin had been fond of the girl, even when Tedros hadn’t been willing to give her a chance.

Tedros raised his eyes to the demon’s. “I had a steward named Lady Gremlaine while I was king. She was my father’s steward too, and they’d grown close before he met my mother. So close that I suspected something may have happened between them . . . Something that made my mother fire Lady Gremlaine from the castle soon after I was born.” The prince swallowed. “Before Lady Gremlaine died, I asked her whether the Snake was her son. Whether he was her and my father’s son. She never said yes. But . . .”

“. . . she suggested it,” Nicola’s voice prodded, the demon looking almost gentle.

Tedros nodded, his throat constricting. “She said she’d done something terrible. Before I was born.” Sweat dripped down his forehead as he relived the moment in the attic, Lady Gremlaine clutching a bloody hammer, her hair wild, her eyes manic. “She said she’d done something my father never knew. But she’d fixed it. She’d made sure the child would never be found. He’d grow up never knowing who he was . . .”

Tedros’ voice caught.

The demon was frozen still. For the first time no one spoke through it.

“So Rhian could be telling the truth,” said Professor Dovey’s voice finally, a remote whisper. “He could be the real king.”

“The son of Lady Gremlaine and your father,” Hester’s voice agreed. “Japeth too.”

Tedros sat up straighter. “We don’t know that. Maybe there’s an explanation. Maybe there’s something she didn’t tell me. I found letters between Lady Gremlaine and my father. In her house. Lots of them. Maybe they explain what she really meant. . . . We need to read those letters . . . I don’t know where they are now—” His eyes glistened. “It can’t be true. Rhian can’t be my brother. He can’t be the heir.” He looked at the demon pleadingly. “Can he?”

“I don’t know,” said Hester, low and grim. “But if he is, then either your brother kills you or you kill him. This can’t end any other way.”

Suddenly they heard the dungeon door open.

Tedros squinted through the bars.

Voices and shadows stretched down the stairway at the end of the hall. The Snake glided into view first, followed by three pirates wielding trays slopped with gruel.

The pirates set down the gruel at the floor of the first two cells—the one with Tedros’ crewmates and the one with Professor Dovey—and kicked the trays through the gaps along with dog bowls of water.

The Snake, meanwhile, walked straight towards Tedros’ cell, his green mask flashing in the torchlight.

Panicked, Hester’s demon flew upwards and Tedros watched it flail around, struggling to find a shadow on the ceiling to hide in. But with its red skin, the demon stuck out like an eyesore—

Then the Snake appeared through the cell bars.

Instantly, the green scims on his mask dispersed, revealing his face to Tedros for the first time.

Tedros gaped back at him, Rhian’s ghostly twin, his lean body fitted in shiny black eels, the suit newly restored as if he’d never been wounded in battle at all. As if he was the strongest he’d ever been.

How?

The Snake seemed to sense what he was thinking and gave him a sly grin.

A shadow fluttered over their heads—

The Snake’s eyes shot up, searching the top of Tedros’ cell, his pupils scanning left and right. He raised a glowing fingertip, coated with scims, and flooded the ceiling with green light.

Tedros blanched, his stomach in his throat. . . .

But there was nothing on the ceiling except a slow-moving worm.

Japeth’s eyes slid back down to Tedros, his fingerglow dissipating.

That’s when Tedros noticed Hester’s demon on the wall behind the Snake, crawling into the boy’s shadow. Tedros quickly averted his eyes from the demon, his heart jumping hurdles.

The Snake gazed at Tedros’ bashed-up face. “Not so pretty anymore, are you.”

It was the way he said it that snapped Tedros to attention, the boy’s tone dripping with disdain. He wasn’t some masked creature anymore. He had a face. He was human now, this Snake. He could be defeated.

Tedros bared his teeth, glaring hard at the savage who’d killed Chaddick, killed Lancelot, and smeared his father’s name. “We’ll see what you look like when I ram my sword through your mouth.”

“So strong you are,” the Snake cooed. “Such a man.” He reached out and caressed Tedros’ cheek—

Tedros slapped his hand away so hard it struck the cell bars, the bone of the Snake’s wrist cracking against metal. But the pale-faced boy didn’t flinch. He just smirked at Tedros, relishing the silence.

Then he pulled the black dungeon key from his sleeve. “I wish I could say this was a social call, but I’m here on behalf of my brother. After she had supper with the king tonight, Princess Sophie was given permission by King Rhian to release one of you.” He glanced down the hall and saw the rest of the crew poking their heads out of the cell at the other end, wide-eyed and listening. “That’s right. One of you who will no longer live in the dungeons and instead be allowed to work in the castle as the princess’s servant, under King Rhian’s eye. One of you whose life will be spared . . .”

The Snake looked back at Tedros. “. . . for now.”

Tedros bolted straight as an arrow. “She picked me.”

In a flash, all doubts Tedros had about Sophie vanished. He should have never mistrusted her. Sophie didn’t want him dead. She didn’t want him to suffer. No matter how much they’d hurt each other in the past.

Because Sophie would do anything for Agatha. And Agatha would do anything for Tedros. Which meant Sophie would do anything to save Tedros’ life, including finding a way to convince a usurping king to set his enemy free.

How had she done it? How had she gotten Rhian on her side?

He’d hear the story soon enough.

Tedros grinned at the Snake. “Get moving, scum. Princess’s orders,” he said. “Open the door.”

The Snake didn’t.

“Let me out,” Tedros commanded, face reddening.

The Snake stayed still, the prison key glinting between his fingers.

“She picked me!” Tedros snarled, gripping the bars. “Let me out!”

Instead, the Snake just put his face to the prince’s . . . and smiled.

SOPHIE

The Dinner Game

Earlier that evening, the pirates Beeba and Aran brought Sophie down from the Map Room for dinner.

Rhian and Japeth were already halfway through their first course.

“It needs to be harsh. A warning,” she heard Japeth saying in the refurbished Gold Tower dining room. “Lionsmane’s first tale should instill fear.”

“Lionsmane should give people hope,” said Rhian’s voice. “People like you and me who grew up without any.”

“Mother is dead because she believed in hope,” said his brother.

“And yet, Mother’s death is the reason both of us are in this room,” said Rhian.

As she neared the door, all Sophie heard was silence. Then—

“Supporters of Tedros are protesting tonight in Camelot Park,” said Japeth. “We should ride in and kill them all. That should be Lionsmane’s first tale.”

“Killing protestors will lead to more protests,” said Rhian. “That’s not the story I want to tell.”

“You weren’t afraid of bloodshed when it got you the throne,” said Japeth snidely.

“I’m king. I’ll write the tales,” said Rhian.

“It’s my pen,” Japeth retorted.

“It’s your scim,” said Rhian. “Look, I know it isn’t easy. Serving as my liege. But there can only be one king, Japeth. I know why you’ve helped me. I know what you want. What both of us want. But to get it, I need the Woods on my side. I need to be a good king.”

Japeth snorted. “Every good king ends up dead.”

“You have to trust me,” Rhian pressed. “The same way I trust you.”

“I do trust you, brother,” said Japeth, softening. “It’s that devious little minx I don’t trust. Suppose you start listening to her instead of me?”

Rhian snorted. “As likely as me growing horns. Speaking of the minx.” He laid down his fork on his plate of rare, freckled deer meat and looked up coldly from the decadent table, his crown reflecting his blue-and-gold suit.

“I heard guards pounding on the Map Room door, Sophie. If you can’t make it to dinner on time, then your friends in the dungeon won’t get dinner at all—” He stopped.

Sophie stood beneath the new Lion-head chandelier, wearing the dress they’d left for her. Only she’d slashed the prim white frock in half, ruffled the bottom into three layers (short, shorter, shortest), hiked them high over her knees, and lined the seams of the dress with wet, globby beads, each filled with different colored ink. Crystal raindrops dangled from her ears; silver shadow burnished her eyelids; her lips were coated sparkly red; and she’d crowned her hair with origami stars, made from the parchment she’d ripped out of the wedding books. All in all, instead of the chastened princess the king might have expected after their encounter in the Map Room, Sophie had emerged looking both like a birthday cake and a girl jumping out of one.

The pirates with Sophie looked just as stunned as the king.

“Leave us,” Rhian ordered them.

The moment they did, Japeth launched to his feet, his pale cheeks searing red. “That was our mother’s dress.”

“It still is,” Sophie said. “And I doubt she would have appreciated you gussying up girls you’ve kidnapped in her old clothes. The real question is why you asked me to wear this dress at all. Is it to make me feel like you own me? Is it because I remind you of your dear departed mum? Or is it something else? Hmm . . . In any case, you told me what to wear. Not how to wear it.” She gave a little shimmy, the light catching the colorful gobs on the dress like drops of a rainbow.

The Snake glared at her, scims sliding faster on his body. “You dirty shrew.”

Sophie took a step towards him. “Snakeskin is a specialty. Imagine what I could make out of your suit.”

Japeth lunged towards her, but Sophie thrust out her palm—

“Ever wonder what map ink is made out of?” she asked calmly.

Japeth stopped midstride.

“Iron gall,” said Sophie, green eyes shifting from the Snake to Rhian, who was still seated, watching her between tall candles in the Lion-themed centerpiece. “It’s the only substance that can be dyed multiple colors and last for years without fading. Most maps are inked with iron gall, including yours in the Map Room. The ones you enchanted to track me and my friends. Do you know what else iron gall is used for?”

Neither twin answered.

“Oh, silly me, I learned about it in my Curses class at school and you boys didn’t get into my school,” said Sophie. “Iron gall is a blood poison. Ingest it and it brings instant death. But let’s say I dab a touch on my skin. It would sap the nutrients from my blood, while keeping me alive, just barely, meaning any vampiric freak who might suddenly need my blood . . . well, they would get poisoned too. And it happens this entire dress—your mother’s dress, as you point out—is now dotted in pearls of iron gall I extracted from your maps, using the most basic of first-year spells. Which means the slightest wrong move and—poof!—it’ll smear onto my skin in just the right dose. And then my blood won’t be very useful to you at all, will it? The perils of haute couture, I suppose.” She fluffed the tail of her dress. “Now, darlings. What’s for dinner?”

“Your tongue,” said Japeth. Scims shot off his chest, turning knife-sharp, as they speared towards Sophie’s face. Her eyes widened—

A whipcrack of gold light snapped over the eels, sending them whimpering back into the Snake’s body.

Stunned, Japeth swung to his brother sitting next to him, whose gold fingerglow dimmed. Rhian didn’t look at him, his lips twisted, as if suppressing a smile.

“She needs to be punished!” Japeth demanded.

Rhian tilted his head, taking in Sophie from a different angle. “You have to admit . . . the dress does look better.”

Japeth was startled. Then his cheekbones hardened. “Careful, brother. Your horns are growing.” Scims coated Japeth’s face, re-forming his mask. He kicked over his chair, its pattern of Lions skidding across the floor. “Enjoy dinner with your queen,” he seethed, striding out of the room. A scim shot off him and hissed at Sophie, before flying after its master.

Sophie’s heart throttled as she listened to Japeth’s footsteps fade.

He’ll have his revenge, she thought. But for now, she had Rhian’s undivided attention.

“A queen in the castle will take him some getting used to,” said the king. “My brother isn’t fond of—”

“Strong females?” said Sophie.

“All females,” said Rhian. “Our mother left that dress for the bride of whichever of us married first. Japeth has no interest in a bride. But he is very attached to that dress.” Rhian paused. “It isn’t poisoned at all, is it?”

“Touch me and find out,” Sophie replied.

“No need. I know a liar when I see one.”

“Mirrors must be especially challenging, then.”

“Maybe Japeth is right,” said Rhian. “Maybe I should relieve you of that tongue.”

“That would make us even,” said Sophie.

“How’s that?” said Rhian.

“With you missing your soul and all,” said Sophie.

Silence spread over the hall, cold and thick. Through the wide bay windows, thunderclouds gathered over Camelot village in the valley.