Полная версия

Wild Swans

WILD

SWANS

Three Daughters of China

JUNG CHANG

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1991

This 25th anniversary edition published 2016

Copyright © Globalflair 1991, 2003

Jung Chang asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007176151

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007379873

Version: 2018-05-14

Praise

‘Of all the personal histories to have emerged out of China’s twentieth-century nightmare, Wild Swans is the most deeply thoughtful and the most heart-rending I’ve read. It moves, in part, like a ghastly oriental fairytale, but the authority and the reticent passion with which Jung Chang speaks her memories—and those of others—is unmistakable.’

COLIN THUBRON, Spectator

‘Wild Swans is a very unusual masterpiece. Everything about it is extraordinary. Not only has it been a popular bestseller, because it is impossible to put down; it has also received the most serious critical attention. The book arouses all the emotions, such as pity and terror, that great tragedy is supposed to evoke, and also a complex mixture of admiration, despair and delight at seeing a luminous intelligence directed at the heart of darkness.’

MINETTE MARRIN, Sunday Telegraph

‘Mesmerising. Like all great stories of survival, no matter what tragedies and horrors are encountered along the way, Wild Swans is ultimately an uplifting book: it is the courage and spirit of this family which will, I believe, be my abiding impression (even if memories of the horrors endured will take a long time to fade).’

ANTONIA FRASER, The Times

‘A quite exceptional book. Jung Chang is the classic storyteller, describing in measured tones the almost unbelievable.’

PENELOPE FITZGERALD, London Review of Books

‘ Wild Swans has stayed in my mind all year. Quite unforgettable.’

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF, Times Literary Supplement

‘An extraordinary story, popular history at its most compelling. Her readiness to record life’s small pleasures as well as its looming horrors is not only an index of Jung Chang’s honesty and good humour, it is a part of what makes Wild Swans so fascinating. To compare Wild Swans to sagas of the kind that fill the bestseller lists may seem to trivialise the real and deadly seriousness of its subject matter, but the book offers many of the pleasures of good historical fiction.’

LUCY HUGHES-HALLETT, Independent

‘Riveting, an extraordinary epic. A work of true, living history drawing deep on family memories, an unmatchable insight into the making of modern China and the impact of war and totalitarianism on the destinies of a quarter of the human race.’

RICHARD HELLER, Mail on Sunday

‘A huge tour de force.’

DEREK DAVIES, Financial Times

‘Immensely moving and unsettling; an unforgettable portrait of the brain-death of a nation.’

J. G. BALLARD

Dedication

To my grandmother and my fatherwho did not live to see this book

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Family Tree

Chronology

Author’s Note

Map

1 ‘Three-Inch Golden Lilies’

2 ‘Even Plain Cold Water Is Sweet’

3 ‘They All Say What a Happy Place Manchukuo Is’

4 ‘Slaves Who Have No Country of Your Own’

5 ‘Daughter for Sale for 10 Kilos of Rice’

6 ‘Talking about Love’

7 ‘Going through the Five Mountain Passes’

8 ‘Returning Home Robed in Embroidered Silk’

Plates Section 1

9 ‘When a Man Gets Power, Even His Chickens and Dogs Rise to Heaven’

10 ‘Suffering Will Make You a Better Communist’

11 ‘After the Anti-Rightist Campaign No One Opens Their Mouth’

12 ‘Capable Women Can Make a Meal without Food’

13 ‘Thousand-Gold Little Precious’

14 ‘Father Is Close, Mother Is Close, but Neither Is as Close as Chairman Mao’

15 ‘Destroy First, and Construction Will Look After Itself’

16 ‘Soar to Heaven, and Pierce the Earth’

17 ‘Do You Want Our Children to Become “Blacks”?’

18 ‘More Than Gigantic Wonderful News’

19 ‘Where There Is a Will to Condemn, There Is Evidence’

20 ‘I Will Not Sell My Soul’

Plates Section 2

21 ‘Giving Charcoal in Snow’

22 ‘Thought Reform through Labour’

23 ‘The More Books You Read, the More Stupid You Become’

24 ‘Please Accept My Apologies That Come a Lifetime Too Late’

25 ‘The Fragrance of Sweet Wind’

26 ‘Sniffing after Foreigners’ Farts and Calling Them Sweet’

27 ‘If This Is Paradise, What Then Is Hell?’

28 ‘Fighting to Take Wing’

Epilogue

Afterword

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

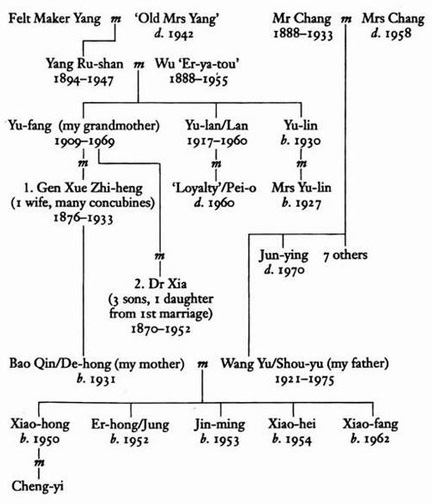

Family Tree

Author’s Note

My name ‘Jung’ is pronounced ‘Yung.’

The names of members of my family and public figures are real, and are spelled in the way by which they are usually known. Other personal names are disguised.

Two difficult phonetic symbols: X and Q are pronounced, respectively, as sh and ch.

In order to describe their functions accurately, I have translated the names of some Chinese organizations differently from the Chinese official versions. I use ‘the Department of Public Affairs’ rather than ‘the Department of Propaganda’ for xuan-chuan-bu, and ‘the Cultural Revolution Authority’ rather than ‘the Cultural Revolution Group’ for zhong-yang-wen-ge.

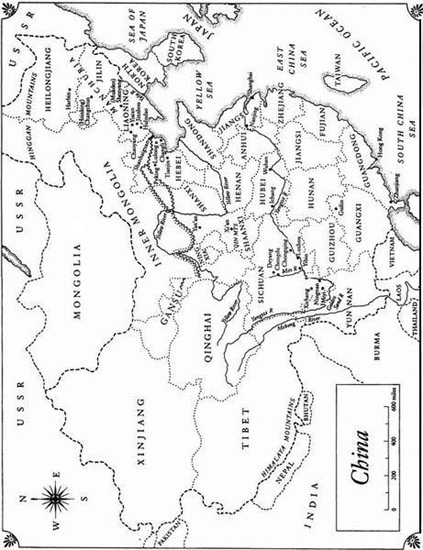

MAP

1

‘Three-Inch Golden Lilies’

Concubine to a Warlord General

1909–1933

At the age of fifteen my grandmother became the concubine of a warlord general, the police chief of a tenuous national government of China. The year was 1924 and China was in chaos. Much of it, including Manchuria, where my grandmother lived, was ruled by warlords. The liaison was arranged by her father, a police official in the provincial town of Yixian in southwest Manchuria, about a hundred miles north of the Great Wall and 250 miles northeast of Peking.

Like most towns in China, Yixian was built like a fortress. It was encircled by walls thirty feet high and twelve feet thick dating from the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907), surmounted by battlements, dotted with sixteen forts at regular intervals, and wide enough to ride a horse quite easily along the top. There were four gates into the city, one at each point of the compass, with outer protecting gates, and the fortifications were surrounded by a deep moat.

The town’s most conspicuous feature was a tall, richly decorated bell tower of dark brown stone, which had originally been built in the sixth century when Buddhism had been introduced to the area. Every night the bell was rung to signal the time, and the tower also functioned as a fire and flood alarm. Yixian was a prosperous market town. The plains around produced cotton, maize, sorghum, soybeans, sesame, pears, apples, and grapes. In the grassland areas and in the hills to the west, farmers grazed sheep and cattle.

My great-grandfather, Yang Ru-shan, was born in 1894, when the whole of China was ruled by an emperor who resided in Peking. The imperial family were Manchus who had conquered China in 1644 from Manchuria, which was their base. The Yangs were Han, ethnic Chinese, and had ventured north of the Great Wall in search of opportunity.

My great-grandfather was the only son, which made him of supreme importance to his family. Only a son could perpetuate the family name—without him, the family line would stop, which, to the Chinese, amounted to the greatest possible betrayal of one’s ancestors. He was sent to a good school. The goal was for him to pass the examinations to become a mandarin, an official, which was the aspiration of most Chinese males at the time. Being an official brought power, and power brought money. Without power or money, no Chinese could feel safe from the depredations of officialdom or random violence. There had never been a proper legal system. Justice was arbitrary, and cruelty was both institutionalized and capricious. An official with power was the law. Becoming a mandarin was the only way the child of a non-noble family could escape this cycle of injustice and fear. Yang’s father had decided that his son should not follow him into the family business of felt-making, and sacrificed himself and his family to pay for his son’s education. The women took in sewing for local tailors and dressmakers, toiling late into the night. To save money, they turned their oil lamps down to the absolute minimum, causing lasting damage to their eyes. The joints in their fingers became swollen from the long hours.

Following the custom, my great-grandfather was married young, at fourteen, to a woman six years his senior. It was considered one of the duties of a wife to help bring up her husband.

The story of his wife, my great-grandmother, was typical of millions of Chinese women of her time. She came from a family of tanners called Wu. Because her family was not an intellectual one and did not hold any official post, and because she was a girl, she was not given a name at all. Being the second daughter, she was simply called ‘Number Two Girl’ (Er-ya-tou). Her father died when she was an infant, and she was brought up by an uncle. One day, when she was six years old, the uncle was dining with a friend whose wife was pregnant. Over dinner the two men agreed that if the baby was a boy he would be married to the six-year-old niece. The two young people never met before their wedding. In fact, falling in love was considered almost shameful, a family disgrace. Not because it was taboo—there was, after all, a venerable tradition of romantic love in China—but because young people were not supposed to be exposed to situations where such a thing could happen, partly because it was immoral for them to meet, and partly because marriage was seen above all as a duty, an arrangement between two families. With luck, one could fall in love after getting married.

At fourteen, and having lived a very sheltered life, my great-grandfather was little more than a boy at the time of his marriage. On the first night, he did not want to go into the wedding chamber. He went to bed in his mother’s room and had to be carried in to his bride after he fell asleep. But, although he was a spoiled child and still needed help to get dressed, he knew how to ‘plant children’, according to his wife. My grandmother was born within a year of the wedding, on the fifth day of the fifth moon, in early summer 1909. She was in a better position than her mother, for she was actually given a name: Yu-fang. Yu, meaning ‘jade’, was her generation name, given to all the offspring of the same generation, while Fang means ‘fragrant flowers’.

The world she was born into was one of total unpredictability. The Manchu empire, which had ruled China for over 260 years, was tottering. In 1894–95 Japan attacked China in Manchuria, with China suffering devastating defeats and loss of territory. In 1900 the nationalist Boxer Rebellion was put down by eight foreign armies, contingents of which had stayed on, some in Manchuria and some along the Great Wall. Then in 1904–5 Japan and Russia fought a major war on the plains of Manchuria. Japan’s victory made it the dominant outside force in Manchuria. In 1911 the five-year-old emperor of China, Pu Yi, was overthrown and a republic was set up with the charismatic figure of Sun Yat-sen briefly at its head.

The new republican government soon collapsed and the country broke up into fiefs. Manchuria was particularly disaffected from the republic, since the Manchu dynasty had originated there. Foreign powers, especially Japan, intensified their attempts to encroach on the area. Under all these pressures, the old institutions collapsed, resulting in a vacuum of power, morality, and authority. Many people sought to get to the top by bribing local potentates with expensive gifts like gold, silver, and jewellery. My great-grandfather was not rich enough to buy himself a lucrative position in a big city, and by the time he was thirty he had risen no higher than an official in the police station of his native Yixian, a provincial backwater. But he had plans. And he had one valuable asset—his daughter.

My grandmother was a beauty. She had an oval face, with rosy cheeks and lustrous skin. Her long, shiny black hair was woven into a thick plait reaching down to her waist. She could be demure when the occasion demanded, which was most of the time, but underneath her composed exterior she was bursting with suppressed energy. She was petite, about five feet three inches, with a slender figure and sloping shoulders, which were considered the ideal.

But her greatest assets were her bound feet, called in Chinese ‘three-inch golden lilies’ (san-tsun-gin-lian). This meant she walked ‘like a tender young willow shoot in a spring breeze’, as Chinese connoisseurs of women traditionally put it. The sight of a woman teetering on bound feet was supposed to have an erotic effect on men, partly because her vulnerability induced a feeling of protectiveness in the onlooker.

My grandmother’s feet had been bound when she was two years old. Her mother, who herself had bound feet, first wound a piece of white cloth about twenty feet long round her feet, bending all the toes except the big toe inward and under the sole. Then she placed a large stone on top to crush the arch. My grandmother screamed in agony and begged her to stop. Her mother had to stick a cloth into her mouth to gag her. My grandmother passed out repeatedly from the pain.

The process lasted several years. Even after the bones had been broken, the feet had to be bound day and night in thick cloth because the moment they were released they would try to recover. For years my grandmother lived in relentless, excruciating pain. When she pleaded with her mother to untie the bindings, her mother would weep and tell her that unbound feet would ruin her entire life, and that she was doing it for her own future happiness.

In those days, when a woman was married, the first thing the bridegroom’s family did was to examine her feet. Large feet, meaning normal feet, were considered to bring shame on the husband’s household. The mother-in-law would lift the hem of the bride’s long skirt, and if the feet were more than about four inches long, she would throw down the skirt in a demonstrative gesture of contempt and stalk off, leaving the bride to the critical gaze of the wedding guests, who would stare at her feet and insultingly mutter their disdain. Sometimes a mother would take pity on her daughter and remove the binding cloth; but when the child grew up and had to endure the contempt of her husband’s family and the disapproval of society, she would blame her mother for having been too weak.

The practice of binding feet was originally introduced about a thousand years ago, allegedly by a concubine of the emperor. Not only was the sight of women hobbling on tiny feet considered erotic, men would also get excited playing with bound feet, which were always hidden in embroidered silk shoes. Women could not remove the binding cloths even when they were adults, as their feet would start growing again. The binding could only be loosened temporarily at night in bed, when they would put on soft-soled shoes. Men rarely saw naked bound feet, which were usually covered in rotting flesh and stank when the bindings were removed. As a child, I can remember my grandmother being in constant pain. When we came home from shopping, the first thing she would do was soak her feet in a bowl of hot water, sighing with relief as she did so. Then she would set about cutting off pieces of dead skin. The pain came not only from the broken bones, but also from her toenails, which grew into the balls of her feet.

In fact, my grandmother’s feet were bound just at the moment when foot-binding was disappearing for good. By the time her sister was born in 1917, the practice had virtually been abandoned, so she escaped the torment.

However, when my grandmother was growing up, the prevailing attitude in a small town like Yixian was still that bound feet were essential for a good marriage—but they were only a start. Her father’s plans were for her to be trained as either a perfect lady or a high-class courtesan. Scorning the received wisdom of the time—that it was virtuous for a lower-class woman to be illiterate—he sent her to a girls’ school that had been set up in the town in 1905. She also learned to play Chinese chess, mah-jongg, and go. She studied drawing and embroidery. Her favourite design was mandarin ducks (which symbolize love, because they always swim in pairs), and she used to embroider them onto the tiny shoes she made for herself. To crown her list of accomplishments, a tutor was hired to teach her to play the qin, a musical instrument like a zither.

My grandmother was considered the belle of the town. The locals said she stood out ‘like a crane among chickens’. In 1924 she was fifteen, and her father was growing worried that time might be running out on his only real asset—and his only chance for a life of ease. In that year General Xue Zhi-heng, the inspector general of the Metropolitan Police of the warlord government in Peking, came to pay a visit.

Xue Zhi-heng was born in 1876 in the country of Lulong, about a hundred miles east of Peking, and just south of the Great Wall, where the vast North China plain runs up against the mountains. He was the eldest of four sons of a country schoolteacher.

He was handsome and had a powerful presence, which struck all who met him. Several blind fortune-tellers who felt his face predicted he would rise to a powerful position. He was a gifted calligrapher, a talent held in high esteem, and in 1908 a warlord named Wang Huai-qing, who was visiting Lulong, noticed the fine calligraphy on a plaque over the gate of the main temple and asked to meet the man who had done it. General Wang took to the thirty-two-year-old Xue and invited him to become his aide-de-camp.

He proved extremely efficient, and was soon promoted to quartermaster. This involved extensive travelling, and he started to acquire food shops of his own around Lulong and on the other side of the Great Wall, in Manchuria. His rapid rise was boosted when he helped General Wang to suppress an uprising in Inner Mongolia. In almost no time he had amassed a fortune, and he designed and built for himself an eighty-one-room mansion at Lulong.

In the decade after the end of the empire, no government established authority over the bulk of the country. Powerful warlords were soon fighting for control of the central government in Peking. Xue’s faction, headed by a warlord called Wu Pei-fu, dominated the nominal government in Peking in the early 1920s. In 1922 Xue became inspector general of the Metropolitan Police and joint head of the Public Works Department in Peking. He commanded twenty regions on both sides of the Great Wall, and more than 10,000 mounted police and infantry. The police job gave him power; the public works post gave him patronage.

Allegiances were fickle. In May 1923 General Xue’s faction decided to get rid of the president, Li Yuan-hong, whom it had installed in office only a year earlier. In league with a general called Feng Yu-xiang, a Christian warlord, who entered legend by baptizing his troops en masse with a firehose, Xue mobilized his 10,000 men and surrounded the main government buildings in Peking, demanding the back pay which the bankrupt government owed his men. His real aim was to humiliate President Li and force him out of office. Li refused to resign, so Xue ordered his men to cut off the water and electricity to the presidential palace. After a few days, conditions inside the building became unbearable, and on the night of 13 June President Li abandoned his malodorous residence and fled the capital for the port city of Tianjin, seventy miles to the southeast.

In China the authority of an office lay not only in its holder but in the official seals. No document was valid, even if it had the president’s signature on it, unless it carried his seal. Knowing that no one could take over the presidency without them, President Li left the seals with one of his concubines, who was convalescing in a hospital in Peking run by French missionaries.

As President Li was nearing Tianjin his train was stopped by armed police, who told him to hand over the seals. At first he refused to say where he had hidden them, but after several hours he relented. At three in the morning General Xue went to the French hospital to collect the seals from the concubine. When he appeared by her bedside, the concubine at first refused even to look at him: ‘How can I hand over the president’s seals to a mere policeman?’ she said haughtily. But General Xue, resplendent in his full uniform, looked so intimidating that she soon meekly placed the seals in his hands.