Полная версия

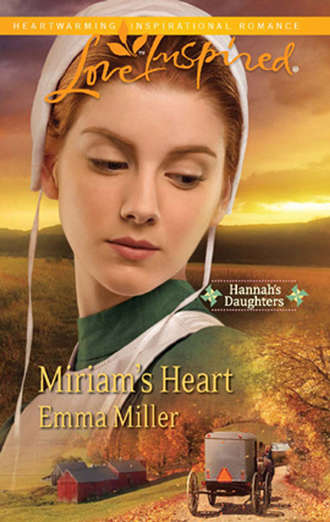

Miriam's Heart

“He likes Miriam,” Susanna supplied, smiling and nodding. “He always comes and talks, talks, talks to her at the sale. And sometimes he buys her a soda—orange, the kind she likes. Ruffie says that Miriam had better watch out, because Mennonite boys are—”

“Hard workers,” Ruth put in.

Susanna’s eyes widened. “But that’s not what you said,” she insisted. “You said—”

Anna tipped over her glass, spilling water on Susanna’s skirt.

Susanna squealed and jumped up. “Oops.” She giggled. “You made a mess, Anna.”

“I did, didn’t I?” Anna hurried to get a dishtowel to mop up the water on the tablecloth.

“My apron is all wet,” Susanna announced.

“It’s fine,” Miriam soothed. “Eat your breakfast.” She rose to bring the coffeepot to the table and pour Charley another cup. “I heard your father had a tooth pulled last week,” she said, changing the conversation to a safer subject.

After they had eaten, Miriam offered to help Charley unload the hay, but he suggested she finish cleaning up breakfast dishes with her sisters. A load of hay was nothing to him, he said as he went out the door, giving Susanna a wink.

“What did I tell you?” Ruth said when the girls were alone in the kitchen. “People are beginning to talk about you and John Hartman, seeing you at the sale together every week. He’s definitely sweet on you, even Charley noticed.”

“I don’t see him at Spence’s every week,” Miriam argued.

Ruth lifted an eyebrow.

“So he likes to stop for lunch there on Fridays,” Miriam said.

“And visit with you,” Ruth said. “I’m telling you, he likes you and it’s plain enough that Charley saw it.”

“That’s just Charley. You know how he is.” Miriam gestured with her hand. “He’s…protective of us.”

“Of you,” Anna said softly.

“Of all of us,” Miriam insisted. “I haven’t done anything wrong and neither has John, so enough about it already.” She went into the bathroom and quickly braided her hair, pinned it up and covered it with a clean kapp.

When she came back into the kitchen, Anna was washing dishes and Susanna was drying them. Ruth was grating cabbage for the noon meal. “I’ve got outside chores to do so I’m going to go on out if you don’t need me in here,” Miriam said.

Ruth concentrated on the growing pile of shredded cabbage.

Miriam wasn’t fooled. “What? Why do you have that look on your face? You don’t believe me? John is a friend, nothing more. Can’t I have a friend?”

“Of course you can,” Ruth replied. “Just don’t do anything to worry Mam. She has enough on her mind. Johanna—” She stopped, as if having second thoughts about what she was going to say.

“What about Johanna?” Miriam didn’t think her sister Johanna had been herself lately. Johanna lived down the road with her husband and two small children, but sometimes they didn’t see her for a week at a time and that concerned Miriam. When she was first married, Johanna had been up to the house almost every day. Miriam knew her sister had more responsibilities since the babies had come along, but she sometimes got the impression Johanna was hiding something. “Are Jonah and the baby well?”

“Everyone is fine,” Anna said.

“Later,” Ruth promised, glancing meaningfully at Susanna. “I’ll tell you all I know, later.”

“I’ll hold you to it,” Miriam said. She thought about Johanna while she fed and watered the laying hens and the pigs. If no one was sick, what could the problem be? And why hadn’t Mam said anything to her about it? Once she’d finished up with the animals, she went to the barn to give Charley a hand.

Dat had rigged a tackle to a crossbeam and they used the system of ropes and pulleys to hoist the heavy hay bales up into the loft. It was hard work, but with two of them, it went quick enough. They talked about all sorts of things, nothing important, just what was going on in their lives: Ruth and Eli’s wedding, harvesting crops, the next youth gathering.

After sending the last bale up, Miriam walked to the foot of the loft ladder. Charley stood above her, hat off, wiping the sweat off his forehead with a handkerchief. “I’m coming up,” she said.

He moved back and offered his hand when she reached the top rung. She took it, climbed up into the shadowy loft and looked around at the neat stacks of hay. It smelled heavenly. It was quiet here, the only sounds the cooing of pigeons and Charley’s breathing. Charley squeezed her fingers in his and she suddenly realized he was still holding her hand, or she was holding his; she wasn’t quite sure which it was.

She quickly tucked her hand behind her back and averted her gaze, as a small thrill of excitement passed through her.

“Miriam,” he began.

She backed toward the ladder. “I just wanted to see the hay,” she stammered, feeling all off-kilter. She didn’t know why but she felt like she needed to get away from Charley, like she needed to catch her breath. “I’ve got things to do.”

“What you two doin’ up there?” Susanna called up the ladder. “Can I come up?”

“Ne! I’m coming down,” Miriam answered, descending the ladder so fast that her hands barely touched the rungs.

Charley followed her. He jumped off the ladder when he was three feet off the ground and landed beside her with a solid thunk.

“I came to see how Molly is.” Susanna looked at Miriam and then at Charley. “Something wrong?”

Miriam felt her cheeks grow warm. “Ne.” She brushed hay from her apron, feeling completely flustered and not knowing why. She’d held Charley’s hand plenty of times before. What made this time different? She could still feel the strength of his grip and wondered if this feeling of bubbly warmth that reached from her belly to the tips of her toes was temptation. No wonder handholding by unmarried couples was frowned upon by the elders.

“Ne,” Charley repeated. “Nothing wrong.” But he was looking at Miriam strangely.

Something had changed between them in those few seconds up in the hayloft and Miriam wasn’t sure what. She could hear it in Charley’s voice. She could feel it in her chest, the way her heart was beating a little faster than it should be.

Susanna was still watching her carefully. “Anna said to tell you to cut greens if you go in the garden and not to forget to meet Mam.”

The three stood there, looking at each other.

“Guess I should be going,” Charley finally said, awkwardly looking down at his feet.

“Thanks again for bringing the hay, Charley. I can always count on you.” Miriam dared a quick look into his eyes. “You’re like the brother I never had.”

“That’s me. Good old Charley.” He sounded upset with her and she had no idea why.

“Don’t be silly.” She tapped his shoulder playfully. “You’re a lifesaver. You kept me from drowning in the creek, didn’t you?”

“In the creek? Right, like you needed saving.” He laughed, and she laughed with him, easing the tension of the moment.

They walked out of the barn, side by side with Susanna trailing after them, and crossed the yard to the well. Charley drew up a bucket of water, and all three drank deeply from the dipper. Then he went back to the barn to guide the team and wagon down the passageway and out the far doors. By the time he’d turned his horses around and driven out of the yard, Miriam had almost stopped feeling as though she’d somehow let him down. Almost…

Later, in the buggy on the way to the orchard with her mother, Miriam had wanted to tell her about the strange moment in the hayloft with Charley. In a large family, even a loving one, time alone with parents was special. Miriam was a grown woman, but Mam had a way of listening without judging and giving sound advice without seeming to. Miriam valued her mother’s opinion more than anyone’s, even more than Ruth’s and the two of them were the closest among the sisters. But this afternoon, she didn’t want sisterly advice; she didn’t need any more of Ruth’s teasing about her friendship with John Hartman. Today, she needed her mother.

But before she could bring up Charley, she needed to find out what Ruth and Anna had been hinting about after breakfast, concerning Johanna. If Johanna had trouble, it certainly took priority over a silly little touch of a boy’s hand. She was just about to ask about her older sister when Mam gestured for her to pull over into the Amish graveyard and rein in the horse.

Sometimes, Mam came here to visit Dat’s grave, even though it wasn’t something that their faith encouraged. The graves were all neat and well cared for; that went without saying, but no one believed their loved ones were here. Those that had died in God’s grace abided with Him in heaven. Instead of mourning those who had lived out their earthly time, those left behind should be happy for them. But Mam—who’d been born and raised Mennonite—had her quirks and one of them was that she came here sometimes to talk to their father.

When Mam came to Dat’s grave, she usually came alone. This was different and Miriam gave her mother her full attention.

“You know we had a letter from Leah on Monday,” Mam said.

Miriam nodded. Her two younger sisters, Leah and Rebecca, had been in Ohio for over six months caring for their father’s mother and her sister, Aunt Jezebel. Grossmama had broken a hip falling down her cellar stairs a year ago, and although the bone had healed, her general health seemed to be getting worse. Aunt Ida, Dat’s sister, and her husband lived on the farm next to Grossmama, but her own constitution wasn’t the best, and she’d asked Mam for the loan of one of her girls. Mam had sent two, because neither Grossmama nor Aunt Jezebel, at their ages, could be expected to act as a proper chaperone for a young, unbaptized woman. No one, least of all Miriam, had expected the sisters to be away so long.

“What I didn’t tell you,” Mam continued, “was that this arrived on Tuesday from Rebecca.” She removed an envelope from her apron pocket. “You’d best read it yourself.”

Miriam slipped three lined sheets of paper out of the envelope and unfolded them. Rebecca’s handwriting was neat and bold. Her sister had wanted to follow their mother’s example and teach school. She’d gotten special permission from the bishop to continue her education by mail, but in spite of her sterling grades, no teaching positions in Amish schools had opened in Kent County.

Miriam skimmed over the opening and inquiries over Mam’s health to see what Mam was talking about. It wasn’t like her to keep secrets, and the fact that she hadn’t said anything about what was in the letter was out of the ordinary and disturbing.

As she read through the pages, Miriam quickly saw how serious the problem was. According to Rebecca, their grandmother had moved beyond forgetfulness and both sisters were concerned for her safety. Grossmama had never been an easy person to please, and Leah and Rebecca had been chosen to go because they were the best-suited to the job.

Dat had been their grandmother’s only son and she’d never approved of his choice of a bride. She’d made it clear from the beginning that she didn’t like Mam. Even as the years passed, she never missed an opportunity to find fault with her and her daughters. Miriam had always tried to remember her duty to her grandmother and to remain charitable when discussing her with her sisters, but the truth was, the prospect of Grossmama’s extended visit for Ruth’s marriage was something Miriam wasn’t looking forward to.

According to Rebecca’s letter, Grossmama had accidentally started fires in the kitchen twice. She’d taken to rising from her bed in the wee hours and wandering outside in her nightclothes, and was having unexplained bouts of temper, throwing objects at Leah and Rebecca and even at Aunt Jezebel. Grossmama had also begun to tell untruths about them to the neighbors. She refused to take her prescriptions because she was convinced that Aunt Jezebel was trying to poison her.

Miriam finished the letter and dropped it into her lap. “This is terrible,” she said. “What can we do?”

Mam’s eyes glistened with unshed tears. “I’ve been praying for an answer.”

Miriam closed her hand over her mother’s. “But why didn’t you tell us?”

“I’ve talked to your aunt Martha.”

“Aunt Martha?” If anyone could make a situation worse, it would be Dat’s sister. “And…”

“She is Grossmama’s daughter. I’m only a daughter-in-law,” Mam reminded her. “Anyway, Martha thinks that Rebecca may be exaggerating. She thinks we should go on as we are until they come here for the wedding.”

“While Grossmama burns down the house around my sisters?”

Mam laughed. “I hope it’s not that bad. As Rebecca says, she and Leah take turns keeping watch over her and they turn off the gas to the stove at night.”

“But why isn’t Aunt Martha or Aunt Ida or one of the other aunts doing something? She’s their mother!”

“And she was Jonas’s mother, my mother-in-law. God has blessed us, child. We’re better off financially than either of your aunts. Martha’s house is small and she’s already caring for Uncle Reuben’s cousin Roy. If your father was alive, he’d feel it was his duty to care for his mother. We can’t neglect that responsibility because he isn’t here, can we?”

“You mean Grossmama is coming to live with us?” Miriam couldn’t imagine such a thing. Her grandmother would destroy their peaceful home. She was demanding and so strict, she didn’t even want to see children playing on church Sundays. She objected to youth singings and frolics, and most of all, she couldn’t abide animals in the house. She would forbid Irwin to let Jeremiah through the kitchen door.

“Nothing is decided,” Mam said. “I spoke to Johanna on Tuesday evening. I meant to discuss it with the rest of you, but then you had the accident with the hay wagon and the time wasn’t right. I just wanted time alone to tell you about this.”

“Ruth doesn’t know?”

“We’ll share the letter with her when the time is right. She’s so excited about her wedding plans and the new house, I don’t want to spoil this special time for her. And Anna, well, you know how Anna is.”

“She’d look for the best in it,” Miriam conceded. “And she’d probably want to take a van out to Ohio tomorrow and make everything right for everyone.”

Her mother nodded. “You’re sensible, Miriam. And you have a good heart.”

“What do you need me to do, Mam?”

“For now? Pray. Think on this and look into your heart. If what Rebecca says is true, we may have to open our home to your grandmother. If we do, it must be all of us, with no hanging back. We have to do this together.”

“All right,” Miriam promised. Thoughts of Charley and the uncomfortable moment with him faded to the back of her mind. Her family—her mother—needed her. “But what shall we do right now?” she asked.

“Drive the horse to the orchard,” Mam said with a smile. “We’ll need those apples all the more with the wedding coming. We’ve got a lot of applesauce to make.”

“Grossmama hates cinnamon in her applesauce.”

“Does she?” Mam’s eyes twinkled with mischief. “And I was just thinking we should stop at Byler’s store to buy extra.”

Chapter Four

Early Saturday morning, two days after Miriam’s accident with the hay wagon, preparations began for Sunday church at Samuel Mast’s home. Anna, Ruth, Mam and Susanna joined Miriam and most of the other women of their congregation to make Samuel’s house ready for services and the communal meal that followed.

Since Samuel, the Yoders’ closest neighbor, was a widower, he had no wife to supervise the food preparation and cleaning. Neighbors and members of the community always came to assist the host before a church day and Samuel was never at a lack for help. It seemed to Miriam as if every eligible Amish woman in the county, or a woman with a daughter or sister of marrying age, turned out to bake, cook, scrub and sweep until Samuel’s rambling Victorian farmhouse shone like a new penny.

Miriam carried a bowl of potato salad in her right hand and one of coleslaw in her left as she crossed Samuel’s spacious kitchen to a stone-lined pantry beyond. Although the September day was warm, huge blocks of ice in soapstone sinks kept the windowless room cool enough to keep food fresh for the weekend. A large kerosene-driven refrigerator along one wall held a sliced turkey and two sliced hams, as well as a large tray of barbecued chicken legs. Pies and cakes, pickles, chowchows and jars of home-canned peaches weighed down shelves. The widower might not have been a great cook, but he never lacked for delicious food when it came to hosting church.

As Miriam exited the pantry, closing the heavy door carefully behind her, she nearly tripped over Anna, who was down on her hands and knees scrubbing the kitchen linoleum. At the sink, Ruth washed dishes and Johanna dried and put them away while Mam arranged a bouquet of autumn flowers on the oak table. “What can I do to help?” Miriam asked.

Anna dug another rag out of the scrub bucket, wrung it out and tossed it to her. Miriam caught the wet rag, frowning with exaggeration at her sister.

“You asked.” Anna grinned. She knew very well that Miriam’s strong point wasn’t housework, but she also knew that when it came down to it, her sister was a hard worker, no matter what the task.

Chuckling, Miriam got down to assist Anna in finishing the floor. Johanna, who had a good voice, began a hymn in High German, and Miriam, Anna and Ruth joined in. Miriam’s spirits lifted. Work always went faster with many hands and a light heart, and the words to the old song seemed to strike a chord deep inside her. It was strange how scrubbing dirty linoleum could make a person feel a part of God’s great plan.

Aunt Martha had taken over the downstairs living room and adjoining parlor, loudly directing her daughter Dorcas and several other young women in washing windows, polishing the wood floors and arranging chairs. But it didn’t take long for Johanna’s singing to spread through the house. Soon, Dorcas’s off-key soprano and Aunt Martha’s raspy tenor blended with the Yoder girls to make the walls ring with the joyful song of praise.

Samuel’s sister, Louise Stutzman, came down the steep kitchen staircase, leading Samuel’s daughter Mae, just as Johanna finished the chorus of their third hymn. The four-year-old was cranky, but Susanna, who’d come in the back door to find cookies, held out her arms and offered to take the little girl outside to play with the other small children.

“Gladly,” Louise said, ushering Mae in Susanna’s direction.

Susanna’s round face beamed beneath her white kapp. “Don’t worry. I’ll take good care of her.”

“I know you will, Susanna. All the children love you.”

Susanna nodded. “You can bring baby Mae to our libary. Mam says I am the best li-barian there is.”

“Librarian,” Mam corrected gently.

Susanna took a breath, grinned and repeated the word correctly. “Li-brarian!”

“Mam had our old milk house made into a lending library for the neighborhood,” Anna explained. “Susanna helps people find books to take home. And she goes with Miriam to buy new ones that the children will like.”

Louise smiled at Susanna. “That sounds like an important job.”

“It is!” Susanna proclaimed. “You come and see. I’ll find you a good book.” Anna held the door open and Susanna carried a now-giggling Mae outside.

“Susanna has such a sweet spirit,” Louise said. “You’ve been blessed, Hannah.”

“I know,” Mam agreed. “She’s very special to us.”

Miriam liked Samuel’s older sister. She was a jolly person with a big smile and a good heart. She was always patient and kind to Susanna, never assuming that because of her Down syndrome, Susanna was less than safe to be trusted with Mae.

Louise had come from Ohio on Friday and brought Mae along for a visit with her father. When Samuel’s wife died after a long illness, baby Mae was only a few months old. None of Samuel’s family thought that he could manage an infant, since he already had the twins, Peter and Rudy, Naomi and Lori Ann to care for. Reluctantly, Samuel had agreed to let his sisters keep the baby temporarily, with the understanding that when he remarried, Mae would rejoin the family. Louise had offered to take Lori Ann as well, but Samuel wouldn’t part with her.

Everyone thought that Samuel would marry after his year of mourning was up. And considering that he was the father of five, no one would have objected if he’d taken a new wife sooner. But it had been four years since Frieda had passed on, and Samuel seemed no closer to bringing a new bride home than he’d been on the day he’d ridden in the funeral procession to the graveyard.

Samuel made visits to his family in Ohio to see little Mae, and his mother and sisters brought the child to Delaware whenever it was his turn to host church services. The shared time was never very satisfactory for father or daughter. Mae was a difficult child, and Samuel and her sisters and brothers were strangers to her. The neighborhood agreed that the sooner Samuel took a wife and brought his family back together, the better for all.

The problem, as Miriam saw it, was that Samuel hadn’t shown any real interest in any of the marriageable young women in the county or those his sisters paraded before him in Ohio. Samuel Mast was a catch. He was a devout member of the church, had a prosperous farm and a pleasant disposition. And, he was a nice-looking man, strong and healthy and full of fun. No one could understand why he’d waited so long to remarry.

Miriam and the Yoder girls thought they knew why, though.

Despite the difference in their ages—Samuel was eight years younger than Mam—it looked to Miriam and her sisters as if Samuel liked their mother. She and Ruth had discussed the issue many times, usually late at night, when they were in bed. They both thought Samuel was a wonderful neighbor and a good man, but not the right husband for Mam.

Hannah had been widowed two years and, by custom, she should have remarried. The trouble was, she wasn’t ready, and neither were her daughters. Dat had been special and Miriam couldn’t see another man, not even Samuel, sitting at the head of the table and taking charge of their lives. Not yet at least.

Among the Plain people, a wife was supposed to render obedience to her husband. Not that she didn’t have a strong role in the family or in the household; she did. But a woman had to be subservient first to God, and then, to her husband. Miriam couldn’t imagine Mam being subservient to anyone.

Growing up, Miriam had never heard her parents argue. It seemed that Mam had always agreed with every decision Dat ever made, but as Miriam grew older she realized that, in reality, it was often Dat who’d listened to Mam’s advice, especially where their children were concerned. In that way, Mam was different.

Mam had been born a Mennonite and had been baptized into the Amish church before they were married. Miriam sometimes wondered if that was what made her mother so strong-willed and independent. Would another man, even a man as good-natured and as sweet as Samuel, be able to accept Mam’s free spirit? Certainly, he’d ask her to give up teaching school. Married women didn’t work outside the home.

If they married, would Samuel expect Mam to move into his house? What would happen to Dat’s farm? To the Yoder girls, including herself? And what about Irwin? His closest relatives were Norman and Lydia Beachy; he’d lived with them when he first came to Seven Poplars, but that hadn’t worked out well. That was why Irwin now lived with Miriam’s family. If Mam and Samuel were to marry, would Samuel want to send Irwin back to the Beachy farm?

Mam and Miriam and her sisters had made out fine in the two years since Dat’s death. It hadn’t been easy, but they managed. There were a lot of ways a stepfather could disrupt the Yoder household, and thinking about it made Miriam uneasy. Ruth leaving to marry Eli was enough change for one year. Wasn’t it?

“Whoa,” Anna said. “That section of the floor is already done.”

Miriam looked up. As usual, she’d been so deep in her thoughts that she’d forgotten to pay attention to what she was doing. “Oops.”