Полная версия

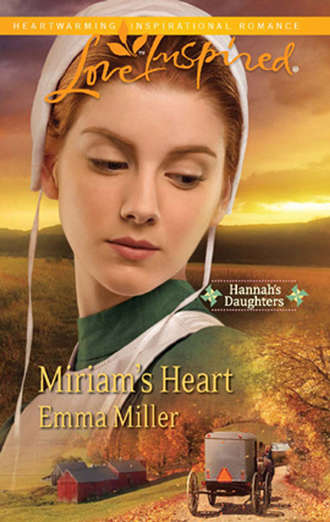

Miriam's Heart

“Charley Byler, what’s wrong with you?” she demanded. “You’re red as a banty rooster. And your clothes are still soaked. Are you taking a chill? You’d best come up to the house, and drink some hot coffee.”

“Can’t.” He backed off as if she were contagious. He couldn’t take the chance she’d touch him again. Not here. Not in front of the Mennonite. “Got to pick up Mary,” he said in a rush. “Thursdays. In Dover.” Every Thursday, his sister cleaned house for an English woman and his mother depended on him to bring her home. “She’ll be expecting me.”

“I forgot,” Miriam said. “That’s too bad. Mam and Anna are cooking an early supper, since we all missed our noon meal. I think they’ve been cooking since Mam got home from school. She wanted me to invite you and John to join us for fried chicken and dumplings. You’re welcome to bring Mary, too.”

“Ne.” He pushed his hat back. “Guess we’ll get home to evening chores.”

Shadows were lengthening in the big barn, but Miriam could read the disappointment on his face. She could tell he wanted to have dinner with them, so why didn’t he just come back after he picked up his sister? She didn’t know what was going on with Charley, but she could tell something was bothering him. She’d known him long enough to know that look on his face.

“Another time for certain,” Charley said, and fled the barn.

“Ya,” she called after him. “Another time.”

“Well, since Charley can’t come, maybe there’s room for me at the table,” Eli said.

She folded her arms, turning to him. “I didn’t think I had to invite you. You’re family. I bet Ruth’s already set a plate for you.” She smiled and he smiled back. Miriam was so happy for Ruth. Eli really did love her, and despite his rocky start in the community, he was going to make a good husband to her.

“Good,” Eli said, “because I’ve worked up such an appetite pulling those horses out of the creek, that I can eat my share and Charley’s, too.”

Eli lived with his uncle Roman and aunt Fannie near the chair shop where he worked as a cabinetmaker, but since he and Ruth had declared their intentions, he ate in the Yoder kitchen more evenings than not.

Miriam looked back at John expectantly. “Supper?”

“I don’t want to impose on your mother.” John knelt beside a bale of straw and closed up his medical case. “Uncle Albert is picking up something at the deli for—”

“You may as well give in,” Miriam interrupted. She rested one hand on her hip. “Mam won’t let you off the farm until she’s stuffed you like a Christmas turkey. We’re all grateful you came so quickly.”

John picked up the chest. “Then, I suppose I should stay. I wouldn’t want to upset Hannah.”

She chuckled, surprised he actually accepted her invitation, but pleased. She knew that he rarely got a home-cooked meal since he’d come to work with his grandfather and uncle in their veterinary practice. None of the three bachelors could cook. When he stopped by her stand at Spence’s, the auction and bazaar where they sold produce and baked goods twice a week, he always looked longingly at the lunch she brought from home. Sometimes, she took pity on him and shared her potato salad, peach pie, or roast beef sandwiches.

Blackie thrust his head over the stall door and nudged her, hay falling from his mouth. Miriam stroked his neck. “You’ve had a rough day, haven’t you, boy?” She took a sugar cube out of her apron pocket and fed it to him, savoring the warmth of his velvety lips against her hand. Then she walked back to check on Molly. The dapple-gray was standing, head down dejectedly, hind foot in the air, unwilling to put any weight on it. That was the hoof that she’d been treating for a stone bruise for the last week, and the thing that concerned John the most. He was afraid that the accident would now make the problem worse.

“Do you think I should stay with her tonight?” Miriam asked, fingering one of her kapp ribbons.

“Nothing more you can do now.” John moved to her side and looked at Molly. “She needs time for that sedative to wear off and then I can get a better idea of how much pain she’s in. I’ll come back and check on her again before I leave and I’ll stop by tomorrow. I need to see that the two of them are healing and I want to keep an eye on that hoof.”

“Supper’s ready!” Ruth pushed open the top of the Dutch door. “And bring your appetites. Mam and Anna have cooked enough food to feed half the church.”

“Charley had to pick up his sister in Dover so he left,” Miriam said, “but John and Eli have promised to eat double to make up for it.”

“Charley can’t eat with us?” Ruth pushed wide the bottom half of the barn door and stepped into the shadowy passageway. “That’s a shame.”

“Ya,” Miriam agreed. “A shame.” Ruth liked Charley. So did Anna, Rebecca, Leah, Johanna, Susanna and especially Mam. The trouble was, ever since the school picnic last spring, when Charley had bought her pie and they’d shared a box lunch, her sisters and Mam acted like they expected the two of them to be a couple. All the girls at church thought the two of them were secretly courting.

“Lucky for you that Charley was nearby when the wagon turned over,” Eli said. He and Ruth exchanged looks. “He’s a good man, Charley.”

Miriam glared at Ruth, who assumed an innocent expression. “It’s John you should thank,” Miriam said. “Without him, we might have lost both Molly and Blackie.”

“But Charley pulled you out of the creek.” Ruth followed Eli out into the barnyard. “He might have saved your life.”

Miriam could barely keep from laughing. “Charley’s the one who nearly drowned me. And the water isn’t deep enough to drown a goose.” She glanced back at John. “Pay no attention to either of them. Since they decided to get married, they’ve become matchmakers.”

“So, you and Charley?” John asked. “Are you—?”

“Ne!” she declared. “He’s like a brother to me. We’re friends, nothing more.” It was true. They were friends, nothing more and no amount of nudging by her family could make her feel differently. When the right man came along, she’d know it…if the right man came along. Otherwise, she was content staying here on the farm, doing the work she loved best and helping her mother and younger sisters.

Ruth led the way up onto the back porch where Miriam and the two men stopped at the outdoor sink to wash their hands. John looked at the large pump bottle of antibacterial soap and raised one eyebrow quizzically.

Miriam chuckled. “What did you expect? Lye soap?”

“No.” He grinned at her. “People just think that…”

“Amish live like George Washington,” she finished. Ruth and Eli were having a tug of war with the towel, but she ignored their silly game and met John’s gaze straight on. “We don’t,” she said. “We use all sorts of modern conveniences—indoor bathrooms, motor-driven washing machines, telephones.” She smiled mischievously. “We even have young, know-it-all Mennonite veterinarians.”

“Ouch.” He grabbed his middle and pretended to be in pain. Then, he shrugged. “Lots of people have strange ideas about my faith, too. My sister gets mistaken for being Amish all the time.”

“Because of her kapp,” Miriam agreed. “Tell her that I had an English woman at Spence’s last week ask me if I was Mennonite.”

“I’ll admit, I didn’t know much about you until I came here. I was surprised that the practice had so many Amish clients.” Eli tossed the towel to him and he offered it to her.

“Of course. We have a lot of animals.” She dried her hands and took a fresh towel off the shelf for him.

She liked John. He had a nice smile. He was a nice-looking young man. Nice, dark brown hair, cropped short in a no-nonsense cut, a straight nose and a good strong chin. Maybe not as pretty in the face as Eli, who was the most handsome man she’d ever seen, but almost as tall.

John was slim, rather than compact like Charley, with the faintest shadow of a dark beard on his cheeks. His fingers were long and slender; his nails clean and trimmed short. When he walked or moved his hands or arms, as he did when he hung the damp towel on the hook, he did it gracefully. John seemed like a gentle man with a quiet air of confidence and strength. It was one of the reasons she believed that he was so good with livestock and maybe why he made her feel so at ease when they were together.

“Miriam, John, come to the table,” Mam called through the screen door. “The food is hot.”

It wasn’t until then that Miriam noticed that Ruth and Eli had gone inside, while she and John had stood there woolgathering and staring at each other. Would he think her slow-witted, that it took her so long to wash the barn off her hands?

“Ya, we’re coming,” she answered. She pushed open the door for John, but he stopped and motioned for her to go through first. He was English in so many ways, yet not. John was an interesting person and she was glad he’d accepted Mam’s invitation to eat with them.

Her sisters, Irwin and Eli were already seated. Mam waved John to the chair at the head of the table, reserved for guests, since her father’s death. She took her own place between Ruth and her twin, Anna. Since John knew everyone but Anna and Susanna, she introduced them before everyone bowed their heads to say grace in silence.

Miriam hadn’t thought she was hungry, but just the smell of the food made her ravenous. Besides the chicken and dumplings, Mam and Anna had made broccoli, coleslaw, green beans and yeast bread. There were pickled beets, mashed potatoes and homemade applesauce. She glanced at John and noticed that his gaze was riveted on the big crockery bowl of slippery dumplings.

Mam asked Irwin to pass the chicken to John and the big kitchen echoed with the sound of clinking forks, the clatter of dishes and easy conversation. Susanna, youngest and most outspoken of her sisters, made Mam and Eli laugh when she screwed up her little round face and demanded to know where John’s hat was.

“My hat?” he asked.

“When you came in, you didn’t put your hat on the coatrack. Eli and Irwin put their hats on the coatrack. Where’s yours?”

Miriam was about to signal Susanna to hush, thinking she would explain later to her that unlike the Amish, Mennonite men didn’t have to wear hats. But then Irwin piped up. “Maybe Molly ate it.”

“Or Jeremiah,” Eli suggested, pointing to Irwin’s little dog, stretched out beside the woodstove.

“Or Blackie,” Anna said.

“Maybe he lost it in the creek,” Ruth teased.

John smiled at Susanna. “Nope,” he said. “I think a frog stole it when we were pulling the horses out.”

“Oh,” Susanna replied, wide-eyed.

John was teasing Susanna, but it was easy for Miriam to see that he wasn’t poking fun at her. He was treating her just as he would Anna or Ruth, if he knew them better. Sometimes, because Susanna had been born with Down syndrome, people didn’t know how to act around her. She was a little slow to grasp ideas or tackle new tasks, but no one had a bigger heart. It made Miriam feel good inside to see John fitting in so well at their table, almost as if the family had known him for years.

“We won’t forget what you did for the horses,” Mam said. “Even if they did eat your hat.”

Everyone laughed at that and Susanna laughed the loudest. It was the best ending to a terrible day that Miriam could ask for, and by the time John had finished his second slice of apple pie, she was sure that he had enjoyed his meal with them as much as they’d enjoyed his company.

Later, after she and John and Ruth and Eli had inspected the horses, John drove away in his pickup. He had one final house call before calling it a day. Eli left as well, wanting to clean the chair shop for his uncle. That left Miriam and Ruth to do the milking. Irwin drove the cows in and offered to help, but Miriam sent him off to see if Mam needed anything. Irwin was shaping up to be a good gardener, but he didn’t know the first thing about milking and usually ended up getting kicked by a cow or spilling a bucket of milk.

Miriam looked forward to this time of day. She and Ruth had always been close friends and soon Ruth would be in her own home with her own cow to milk. Miriam would miss her. She loved her twin Anna dearly; she loved all her sisters, but Ruth was the kind of big sister she could talk to about anything. Of course there were some nights when Miriam might have preferred to milk alone.

“You know he’s sweet on you,” Ruth said. She was milking a black-and-white Holstein cow named Bossy in the next stall. Ruth had her head pushed into Bossy’s sagging middle and two streams of milk hissed into her bucket in a steady rhythm.

“Who likes me?” Miriam stopped a few feet from Bossy’s tail, her empty bucket in one hand and a three-legged milking stool in the other. She’d tied a scarf over her kapp to keep it clean and pushed back her sleeves.

“Charley. He’s going to make someone a fine husband.”

“I know he is. It’s just not going to be me.” Miriam sighed and walked to the next stall where Polly, a brown Jersey, waited patiently, chewing her cud. “And I’m tired of you and Anna trying to make something of it that isn’t.”

“You like the cute vet better?”

Polly swished her tail and Miriam pushed it out of the way as she placed her stool on the cement floor and sat down. “John?”

“Was there another cute vet at supper?”

“He came because we needed him. It’s his job.”

“Ya, but you like him.” Ruth’s voice was muffled by the cow’s belly. “Admit it.”

Miriam took a soapy cloth and carefully washed Polly’s bag. The cow swished her tail again. Miriam dropped the cloth into the washbasin and took hold of one teat. She squeezed and pulled gently and milk squirted into the bucket. “First Charley, then John.”

“He’s Mennonite,” Ruth said.

“I know he’s Mennonite.”

“But you think he’s cute.”

Miriam wished her sister was standing close enough to squirt with a spray of milk. Once Ruth started, there was no stopping her. “Mam invited him to dinner, not me.”

“But you like him. Better than Charley.”

“Maybe I do and maybe I don’t,” she said. “But if you say another word about boys tonight, I’ll dump this bucket of milk over your head.”

It was dusk by the time John got back to the house that was both office and home for him, his grandfather and Uncle Albert. John completed his paperwork, refilled his portable medicine chest and went upstairs to shower. Once he’d changed into clean clothing, he wandered out onto the side porch where the two older men sat with their feet propped up on the rail, sipping tall glasses of lemonade. As always, the three shared the day’s incidents. When his grandfather asked, John began telling them about the accident at the Yoder farm.

The third time John mentioned Miriam’s name, his uncle Albert asked him if he was sweet on her. John shrugged and took a big sip of lemonade.

“She’s Old Order Amish,” his grandfather said.

“I know that,” John replied.

“Miriam, is she one of the twins?” his uncle asked.

“I think so.”

“The big one or the little one?”

“The little one.”

“Pretty as a picture,” Uncle Albert observed.

“Yeah,” John admitted, getting up and attempting a quick escape into the house before they pressed the issue any further.

Truth be told, he was sweet on Miriam Yoder and he was pretty certain she liked him. And it wasn’t just her looks or the physical chemistry between them that attracted him. She was easy to talk to and shared his love of animals. Although he always knew he would marry and have children someday, John hadn’t seriously dated since his final year of vet school, when his girlfriend of three years had broken up with him. Alyssa, the daughter of a Baptist minister, had broken his heart and after that he had filled in what little spare time he had with family. It had been so long that he had forgotten what it felt like to be so strongly attracted to a woman. The fact that Miriam was Amish complicated the matter even further.

His grandfather chuckled. “He’s sweet on her.”

“Good luck with that,” Uncle Albert said. “I’ve heard those Yoder girls can be a handful.”

John paused in the doorway and looked back. “Sometimes,” he said softly, “a handful is just the kind of woman a man is looking for.”

Chapter Three

Miriam and Anna were just setting the table for breakfast the following morning when they heard the sound of a wagon rumbling up their lane. Miriam, who’d showered after morning chores, snatched a kerchief off the peg and covered her damp hair before going to the kitchen door. “It’s Charley,” she called back as she walked out onto the porch. He reined in his father’s team at the hitching rail near the back steps.

“Morning.” The wagon was piled high with bales of hay.

“You’re up and about early,” she said, tucking as much of her hair out of sight as possible. Wet strands tumbled down her back, and she gave up trying to hide them. After all, it was only Charley.

“Where are you off to?” Behind her, Jeremiah yipped and hopped up and down with excitement. “Hush, hush,” she said to the dog. “Irwin! Call him. He’ll frighten Charley’s team.”

Irwin opened the screen door and scooped up the little animal. “Morning, Charley,” he said.

Charley climbed down from the wagon. “I’m coming here,” he said as he tied the horses to the hitching rail. “Here.”

“What?” she asked. Curious, Irwin followed her down the porch steps into the yard, the whining dog in his arms.

Charley laughed. “You wanted to know where I was going, didn’t you?”

She wrinkled her nose. “I don’t understand. We didn’t buy any hay from your father.”

“Ne.” He grinned at her. “But you lost a lot of your load in the creek. My Dat and Samuel and your uncle Reuben wanted to help.”

She sighed. The hay she’d lost had already been paid for. There was no extra money to buy more. “It’s good of you,” she said, “but our checking account—”

“This is a gift to help replace what you lost.”

“All that?” Irwin asked. “That’s a lot.”

She looked at the wagon, mentally calculating the number of bales stacked on it. “We didn’t have that much to begin with,” she said, “and not all our bales were ruined.”

Charley tilted his straw hat with an index finger and chuckled. “Don’t be so pigheaded, Miriam. I’m putting this in your barn. You’ll take it with grace, or explain to your uncle Reuben, the preacher, why you cannot accept a gift from the members of your church who love you.”

Moisture stung the back of her eyelids, and a lump rose in her throat. “Ya,” she managed. “It is kind of you all.”

Charley had always been kind. Since she’d been a child, she’d known that she could always count on him in times of trouble. When her father had died, without being asked Charley had taken over the chores and organized the young men to set up tables for supper after the funeral and carry messages to everyone in the neighborhood. A good man…a pleasant-looking man—even if he did usually need a haircut. But he’s just not the man I’d want for a husband, she thought, recalling her conversation with Ruth last night. Not for me, no matter what everyone else thinks.

He walked toward her, solid, sandy-haired Charley, bits of hay clinging to his pants and shirt, and pale blue eyes dancing. Pure joy of God’s good life, her father called that sparkle in some folks’ eyes. He was such a nice guy, perfect for a friend. Ruth was right, he would make someone a good husband; he would be perfect for sweet Anna. But Charley was a catch and he’d pick a cute little bride with a bit of land and a houseful of brothers, not her dear Plain sister.

“We’re family. We look out for our neighbors.”

She nodded, so full of gratitude that she wanted to hug him. This is what the English never saw, how they lived with an extended family that would never see one of their own do without.

“I’m happy to make the delivery and I’d not turn down a cup of coffee,” Charley said. “Or a sausage biscuit, if it was offered.” He gestured toward the house. “That’s Anna’s homemade sausage I smell, isn’t it? She seasons it better than the butcher shop.”

“Ya,” Irwin said. “It’s Anna’s sausage, fresh ground. And pancakes and eggs.”

Miriam laughed. “We’re just sitting down to breakfast. Would you like to join us?”

“Are Reuben’s sermons long?” Charley chuckled at his own jest as he brushed hay from his pants. “I missed last night’s supper. I’m not going to turn down a second chance at Anna’s cooking.” Then he glanced back toward the barn. “How are your horses?”

“Blackie’s stiff, but his appetite is fine. Molly’s no worse. I got her to eat a little grain this morning, but she’s still favoring that hoof. John said he’d stop by this afternoon.” She followed him up onto the porch and into the house. Irwin and the dog trailed after them.

“Miriam invited me to breakfast,” Charley announced as he entered the kitchen, leaving his straw hat on a peg near the door.

Mam rose from her place. “It’s good to have you.”

“He brought us a load of hay,” Miriam explained, grabbing a plate and extra silverware before sitting down. She set the place setting beside hers and scooted over on the bench to make room for him. “A gift from Uncle Reuben, Samuel and Charley’s father.”

Ruth smiled at him as she passed a plate of buckwheat pancakes to their guest. “It’s good of you. Of all who thought of us.”

“I mean to spread those bales that got wet,” Charley explained, needing no further invitation to heap his plate high with pancakes. “If the rain holds off, it could dry out again. I wouldn’t give it to the horses, but for the cows—”

“We could rake it up and pile it loose in the barn when it dries,” Miriam said, thinking out loud. “That could work. It’s a good idea.”

“A good idea,” Susanna echoed.

The clock on the mantel chimed the half hour. “Ach, I’ll be late for school,” Mam exclaimed. She took another swallow of coffee and got to her feet. When Charley started to rise, she waved him back. “Ne, you eat your fill. It’s my fault I’m running late. The girls and I were chattering like wrens this morning and I didn’t watch the time. Come, Irwin. There will be no excuses of illness today.”

Irwin popped up, rolling his last bit of sausage into a pancake and taking it with him.

“It wouldn’t do for the teacher to be late.” Anna collected Mam’s and Irwin’s dinner buckets and handed them out. “Have a good day.”

“Good day,” Irwin mumbled through a mouthful of sausage and pancake as he dodged out the door. “Watch Jeremiah, Susanna!”

“I will,” she called after him, obviously proud to be given such an important job every day. “He’s a good dog for me,” she announced to no one in particular.

“Don’t forget to meet me at the school after dinner with the buggy.” Mam tied her black bonnet under her chin. “Since there’s only a half day today, we’ve plenty of time to drive to Johnson’s orchard.”

“I won’t,” Miriam answered. Their neighbor, Samuel Mast, who was sweet on Mam, had loaned them a driving horse until Blackie recovered from his injuries. They’d have apples ripe in a few weeks here on the farm, but Mam liked to get an early start on her applesauce and canned apples. The orchard down the road had several early varieties that made great applesauce.

Once their mother was out the door, they continued the hearty meal. Miriam had been up since five and she suspected that Charley had been, too. They were all hungry and it would be hours until dinner. Having him at the table was comfortable; he was like family. Everyone liked him, even Irwin, who was rarely at ease with anyone other than her Mam and her sisters.

The only sticky moments of the pleasant breakfast were when Charley began to ask questions about John. “You say he’s coming back today?”

Miriam nodded. “The stitches need to stay in for a few days, but John wants to have a look at them today.”

“He thinks he has to look at ’em himself? You tell him you could do it? I know something about stitches. We both do.”