Полная версия

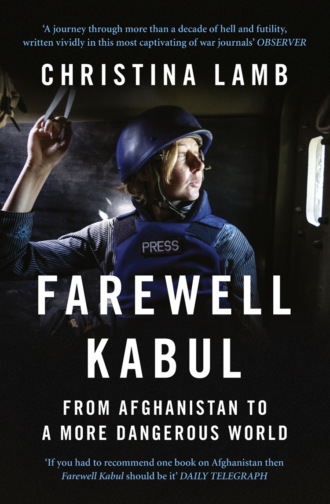

Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World

Yet more than a military failure, this was a political failure. Just as a lack of imagination had failed to predict the possibility of using passenger aeroplanes as weapons, a lack of imagination caused us to assume people wanted the same as us, and that because our enemy were uneducated they were ignorant savages we could easily outsmart. It was a strategy that ignored tribal realities and other people’s national interests, including those of our key partner. Along the way, the West lost the moral high ground by giving positions of power to those the Afghan people most blamed for the war, and by the detention and torture of prisoners, some of whom had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Over those thirteen years I watched with growing incredulity as we fought a war with our hands tied, committed too little too late, became distracted by a new war of our own making based on wrong information, and turned a blind eye as our enemy was being helped by our own ally. Yet only when Osama bin Laden was found living in a house in a Pakistani city, not far from the capital, did it seem to dawn on people that we may have been fighting the wrong war.

Throughout this period I lived in Pakistan, Afghanistan, London and Washington, as well as covering the other war and its aftermath in Iraq, and visiting Saudi Arabia, which was the birthplace of fifteen of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers. I spoke to almost all key decision-makers, including heads of state and generals, as well as embedding with American soldiers and British squaddies actually fighting the wars. Most of all I talked to people on the ground. I travelled the length and breadth of Pakistan, from the tribal areas to the mountain valleys of Swat, from the cities of Quetta, Lahore and Karachi to the jihadist recruiting grounds in madrassas and in remote villages of the Punjab. In Afghanistan my travels took me far beyond Helmand – from the caves of Tora Bora in the south to the mountainous badlands of Kunar in the east; from Herat, city of poets and minarets in the west, to the very poorest province of Samangan in the north, full of abandoned ghost villages. I also travelled to Guantánamo, met Taliban in Quetta and from the Quetta shura, visited jihadi camps in Pakistan, and saw bin Laden’s house just after he was killed. Saddest of all, I met women whom we had made into role models and who had then been shot, raped, or forced to flee the country.

On the way I had several narrow escapes – from being ambushed by Taliban with the first British combat troops in Helmand to travelling on Benazir Bhutto’s bus when it was blown up in Pakistan’s biggest ever suicide bomb. I lost many friends in those years, a number of whom appear in the following pages.

I could not have lived through all this and just walked away. I have written this book because I thought it was a story that needed telling. How it ends is yet to be told.

PART I

GETTING IN

British general to Afghan tribal chief in 1842 during the First Anglo–Afghan War: ‘Why are you laughing?’

Tribal chief: ‘Because I can see how easy it was for you to get your troops in here. What I don’t understand is how you plan to get them out.’

1

Rule Number One

Kabul, Christmas Eve 2001

I sat on the roof of the Mustafa Hotel on the seat of an old Soviet MiG fighter jet and looked out over Kabul feeling happy. Happy endings are few and far between in my foreign correspondent world, where we fly in to report war, misery and disaster in time for our deadlines, then out again back to our comfortable lives, disturbed only by an occasional nightmare or sad memory that floods in unexpectedly to darken a moment.

The hills all around were dotted with tiny wattle houses in squares of beige and sky-blue, melding into each other like a Braque painting. There was ‘Swimming Pool Hill’, named after the Olympic-sized concrete pool the Russians had built on its top, long empty and last used by Taliban to push blindfolded homosexuals to their deaths off the diving tower; ‘TV Mountain’, with a broken antenna and littered with rocket casings from years as a major battleground for rival mujaheddin groups; and ‘Cannon Hill’, where until all the fighting started an old man would fire off a cannon every day at noon, a tradition begun in the nineteenth century by the ‘Iron King’ Abdur Rahman to give his unruly countrymen a sense of time.

Along the tops I could see remains of the old city walls picked out in relief, starting and ending at the Bala Hissar fortress, an ancient polygon of walls which crowned Lion’s Gate Mountain and managed to be both crumbling and imposing. The name means ‘high fort’, and from this perch for centuries ruled Afghan kings (some of whom ended up in its dungeons, the Black Pit) and, long ago, some of the world’s mightiest conquerors. Among them were Timur the Lame, the Tartar despot who levelled cities from Moscow to Baghdad and built towers from the skulls of their people; and Babur, the first Moghul Emperor, who adored Kabul for its gardens, where he counted thirty-two different kinds of tulips. Babur loved this city, describing it as ‘the most pleasing climate in the world … within a day’s ride it is possible to reach a place where the snow never falls. But within two hours one can go where the snow never melts.’

I loved it too, even though it was a long time since Kabul had been a city of gardens. Rather it was a city of ghosts, many of whose bodies were buried in the hills. Some of them were from my own country. Britain had fought two wars with Afghanistan, losing two and perhaps drawing the third. Yet initially the country seemed so benign that when British forces first stormed Kabul Gate in 1838, to oust king Dost Mohammed and install their own king, Shah Shuja, they took with them their wives, hundreds of camels laden with provisions such as smoked salmon, cigars and port, and even packs of hounds for hunting foxes in the Hindu Kush. Wives wrote of swapping tips on growing sweet peas and geraniums with local Afghans1 and of outings to boat on the lake or ice-skate in winter. By January 1842 the British would have fled. The king they had installed on a gilded throne under richly painted ceilings in the Great Hall of the Bala Hissar and described as “a man of great personal beauty”2 ended up slaughtered at its gates. The defeat of what was then the most powerful nation on earth – and slaughter of thousands of its forces – by marauding tribesmen was the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the West in the East.

Yet they went back. In the second war, the British Envoy Sir Louis Cavagnari was hacked to death in his residence inside the fort in September 1879 by tribal brigands angry at not being paid promised stipends, and at British interference in their land. In revenge the British general Frederick Roberts led a column on Kabul called the ‘Army of Retribution’, and had forty-nine tribal leaders hanged from gallows inside the Bala Hissar. He ordered the fort’s destruction as ‘a lasting memorial of our ability to avenge our countrymen’, though in the end it was left. Such was the feared reputation of the land of the Bala Hissar that in 1963 Britain’s Prime Minister Harold Macmillan would declare, ‘Rule number one in politics – Never Invade Afghanistan.’

I had first travelled in these valleys and mountains in the late 1980s when the Russians were being driven out, so was only too familiar with all those stories of Afghanistan as the ‘Graveyard of Empires’. Indeed, Kabul still had a British cemetery, with graves going back to those killed in the First Anglo–Afghan War, if any reminder were needed.

But if we knew those things then, we were not thinking about them. If I shivered, it was because of the cold. The first snow was falling softly, and loud Bollywood music blared discordantly from the street below. On the roof were other journalists from Japan, Italy and Australia, shuffling around their satellite dishes to try to find the right angle to locate satellites in the sky so they could magically transmit their copy to their foreign desks. ‘Oh for fuck’s sake, bring back the Taliban!’ joked one, struggling to be heard over the jarring music. I laughed, catching a snowflake on my tongue and thinking there was nowhere I would rather be.

Everything had happened so quickly it was hard to take in. On 11 September 2001 I had just moved to Portugal with my husband and two-year-old son when my sister-in-law called telling me to switch on the news. We hadn’t yet got a television so we headed to a local piri-piri chicken café which had a large screen to show football matches to English tourists. Watching the planes fly through the brilliant blue sky of a Manhattan morning and smash into the iconic towers of the World Trade Center was impossible to comprehend, no matter how many times we watched.

Then we heard two other passenger planes had crashed – one into the Pentagon and one into a field in Pennsylvania. I held my son tight, for it was clear that nothing would be the same again.

It wasn’t long before the TV commentators were joining the dots to Saudi billionaire’s son Osama bin Laden, who had vowed war on the United States. Soon they were focusing their pointers on maps of Afghanistan where the al Qaeda leader had fought in the 1980s and been living under the protection of the Taliban since 1996.

Who were the Taliban, and their mysterious one-eyed leader Mullah Omar? It was a regime about which the West knew so little that when 9/11 happened, Jonathan Powell, Chief of Staff to British Prime Minister Tony Blair, sent out his staff to buy all the books they could on the Taliban.3 They had only been able to find one – Ahmed Rashid’s Taliban, which had struggled to find a publisher. Now it was a best-seller and everyone had heard of the zealots who wanted to lock away Afghanistan’s women and take the country back to the seventh century.

Editors who had not been in the least interested in goings on in Afghanistan suddenly could not get enough stories of the horrors of life under the Taliban. For weeks we had been writing about the women lashed for wearing nail varnish or white shoes; the men beaten with logs for not having beards as long as two fists; the sports stadiums used for amputations and executions; and the banning of everything from chess to music.

Now, just two months later, they had been driven out. In Kabul, everyone seemed to be out on the streets, hearing each other’s stories, like people inspecting the damage after a massive storm. The reports we were sending were upbeat tales of life beginning again: girls’ schools reopening, women casting off the blue burqas they had been made to wear. On every street there were people hammering Coke and 7 Up cans into satellite dishes. In a teahouse I came across the first meeting of a long-banned chess club; in the bookshop around the corner from the hotel was Shah Mohammad Rais, who had hidden his books to prevent the Taliban burning them. In the National Gallery I found a man with a sponge and bucket washing off the trees and lakes he had painted over faces on artworks so the Taliban would not destroy them.

Most magical of all were the kites flying from the rooftops. On the road up to the Intercontinental Hotel (that wasn’t really an Intercontinental) a parade of tiny kite shops had reopened. Inside each sat a man wrapping bamboo frames with tissue paper then pasting on shapes in bright pinks, yellows and blues like a Matisse collage and finally rolling the string onto giant reels. Each man claimed to be the most famous kite-maker in Kabul. We didn’t know then that the string would be coated with ground glass, and the objective was to cut down kites of other boys (even then, we never saw girls flying kites).

The story I had written that day was of an encounter with British Royal Marines on Chicken Street, a favourite destination back in the days of the hippie trail, with all its little shops selling carpets, shawls, and lapis and garnet stones set into silver rings that would soon blacken. The soldiers were the first arrivals of the International Stabilisation Assistance Force (ISAF), which was quickly nicknamed the International Shopping Assistance Force.

The first foreign troops to enter Kabul since the Russian occupation twelve years earlier, the British were warmly welcomed by locals. After years of civil war, many Afghans saw foreigners as the only way to end the fighting so they could get on with life. The fact that of all people they were British, back for more, seemed to endear them further to the locals. The British soldiers sat on top of their armoured personnel carriers handing out sweets to Afghan children and cigarettes to the men, and all round it was smiles.

‘Hello my sister, what gives?’ Wais Faizi, the hotel’s manager, was a thirty-one-year-old Afghan with a fast-talking New Jersey patois like the car salesman he had once been. ‘The Fonz of Kabul’, we called him. His family had owned the Mustafa for years, until it was seized by communists around the time of the Soviet invasion in 1979, and they had fled to America when he was just a child. They had recently returned to Afghanistan, and had been in the process of converting the Mustafa into a gemstone and money exchange when 9/11 happened and Kabul unexpectedly became the focus of world attention. So they quickly turned it back into a hotel, just in time for the flood of journalists, though with not enough time to actually make the rooms comfortable.

‘Chai sabz?’ Wais handed me a mug of green tea.

‘Tashakor.’ I thanked him. It had about as much taste as old dishwater, but it was warm, tendrils of steam rising in the frigid air, and I cupped my hands gratefully around the sides.

‘Still working on the espresso machine,’ he apologised. He found his home country harder to get used to than we nomad journalists did, and often talked wistfully of Dunkin’ Donuts and Domino’s Pizza. A coffee machine would actually be useless, given how rarely we had electricity; and when it came it was in gadget-destroying bursts. But if anyone could get one, it would be Wais. He’d already turned one of the rooms into a makeshift gym, complete with some dumbbells bought from a warlord, and decorated with posters of his hero Al Pacino.

Wais had even managed to get hold of the only convertible in Kabul, a 1968 Chevy Camaro which had belonged to one of the Afghan princes before the King was deposed, and had taken me for a spin. We’d had a glorious afternoon driving around the ruins of Kabul, children waving in astonishment, carpet-beaters jumping out of the way and men wobbling on their bikes at the sight of a foreign woman in an open-top car and headscarf fancying herself as Grace Kelly.

Next he had promised us a bar, and he was organising a Christmas dinner, for, unbelievably, he had found someone in the Panjshir valley who raised turkeys. It would make a change from the past-their-date tuna ready-meals, peanut butter and white-furred bars of Cadbury’s chocolate we had been living on from Chelsey (sic) Supermarket, where Osama bin Laden’s Arabs used to shop.

I caught another snowflake on the tip of my tongue. ‘Christina jan, don’t eat the snow – it’s full of shit!’ admonished Wais. He meant it literally. Everyone in Kabul seemed to have a permanent cough, and Americans I met loved to tell me the air was full of faecal matter – waste went straight into the streets, and the smoke rising from the houses on the hills was from pats of animal dung that people burned as fuel.

‘No thanks to your horrid pigeons!’ I replied. Wais had recently discovered Kabul’s old Bird Market, which sold anything from tiny orange-beaked finches to strutting roosters, all meant for fighting. There, he had acquired a flock of burbling pigeons which he kept in a glass coop in the open courtyard in the centre of the hotel. Pigeon-flying was popular in Kabul, where houses had flat roofs and people trained them to take off as if by remote control then loop the loop by waving a stick called a tor, with a piece of black cloth on the end. As always in Afghanistan, it wasn’t a benign pastime: the real aim was to try to get someone’s rival flock to land on your rooftop. You could usually tell pigeon-trainers by their beak-scarred hands.

Wais claimed the pigeons reminded him of the blue mosque in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif, a building surrounded by so many white doves that when they take to the air it feels like being inside a just-shaken snowglobe. But to me they were completely different. Pigeons, I reminded him, had left the young Emperor Babur fatherless at thirteen, when his father fell from his dovecote. ‘The pigeons and my father took flight to the next world,’ he’d written in his journal.

‘Why can’t you fly kites instead of pigeons?’ I asked.

‘You of all people should like the pigeons,’ Wais laughed. ‘When they fly they always follow the lead of a female.’

The music stopped, its owner perhaps paid off by some exasperated journalist, and I could hear peals of children’s laughter. Down on the pavement some local street kids were jumping and diving, trying to catch the snow, which was starting to fall more thickly, sending cloth-wrapped figures scurrying to their homes. Soon I would be driven inside too, to one of the freezing glass-partitioned cells with metal bars on the outside that passed for rooms at the Mustafa. But for a moment I wanted to enjoy the rare sight of children playing in this country which had seen more than twenty years of war.

The mood in Washington and Whitehall was also celebratory. Just sixty days after the first US bombing raid on Afghanistan the Taliban were gone, far quicker than Pentagon estimates. They had been driven out by a combination of American B52 bombers and Afghan fighters from the Northern Alliance, a group of mainly Tajik and Uzbek commanders who had started waging war against the Russians in the 1980s, then continued fighting against the Taliban when they took power in the 1990s.

It was an astonishing success, and seemed like a new model of war. Colin Powell, then US Secretary of State, said: ‘We took a Fourth World army – the Northern Alliance – riding horses, walking, living off the land, and married them up with a First World air force. And it worked.’

The Northern Alliance certainly did not consider itself a Fourth World army, and the fact that there was already a fighting force in place well acquainted with the Taliban was a huge advantage. Based in the picturesque Panjshir valley, they were the fighters of a legendary commander, Ahmat Shah Massoud, a poetic figure with a long, aquiline nose, blue eyes and a rolled felt cap, known as the Lion of Panjshir, whom the Russians had never defeated. Under his leadership the Northern Alliance controlled around 9 per cent of Afghanistan in the north-east – the one bit of the country the Taliban had never managed to conquer.

Massoud’s foreign spokesman was his close friend Dr Abdullah Abdullah, a short, dapper-suited ophthalmologist with a penchant for wide ties. His name was really only Abdullah, as like many Afghans he had just one name, but he had taken another ‘Abdullah’ to accommodate the need of the Western media for surnames. Dr Abdullah had repeatedly travelled to America and Britain, warning that Arab terrorists were taking over Afghanistan. He told me he had made ten trips to Washington between 1996, when the Taliban took power, and 2001 asking for help – all to no avail.4 The Americans were not interested in Afghanistan, and had no desire to get involved with a warlord who financed his operations through the trafficking of drugs and lapis lazuli. Massoud was particularly distrusted by the State Department because he received support from Iran and Russia, and because of the fact that he was hated by Pakistan, which the US wanted to keep onside. ‘They just said it was an internal ethnic conflict,’ said Dr Abdullah. Massoud himself spoke at the European Parliament in April 2001, appealing for humanitarian aid for his people and warning that al Qaeda was planning an attack on US soil.

He was hardly a lone voice. George Tenet, who was Director of the CIA at the time, later testified before the 9/11 Commission that the Agency had picked up reports of possible attacks on the United States in June, and said the ‘system was blinking red’ from July 2001. On 12 July Tenet went to Capitol Hill to provide a top-secret briefing for Senators about the rising threat from Osama bin Laden. Only a handful of Senators turned up in S-407, the secure conference room. The CIA Director told them that an attack was not a question of if, but when.

Another warning came in the first meeting between President George W. Bush and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin in a Slovenian castle in July 2001, the American President was taken aback when the former KGB man suddenly raised the subject of Pakistan. ‘He excoriated the Musharraf regime for its support of extremists and for the connections of the Pakistani army and intelligence services to the Taliban and al Qaeda,’ recalled Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s National Security Adviser, who was present. ‘Those extremists were all being funded by Saudi Arabia, he said, and it was only a matter of time until it resulted in a major catastrophe.’5

This was written off as Soviet sour grapes for having lost in Afghanistan. No notice was taken, nor was the Northern Alliance provided with help. It says something about Massoud’s charisma that without Western assistance or much hope of success, he kept his fighters together. ‘He always wore a pakoul [wool cap], and he’d say, “Even if this pakoul is all that remains of Afghanistan I will fight for it,”’ said Ayub Solangi, who had fought with him since the age of sixteen, and had lost all his teeth in torture in Russian prisons.

Two days before 9/11, two Tunisians posing as TV journalists came to his Panjshir headquarters to do an interview. ‘Why do you hate bin Laden?’ they asked him, just before their camera exploded in a blue flash. The assassination of the Taliban’s biggest enemy was widely assumed to be a gift from al Qaeda to their Taliban hosts, to ensure their support as the Bush administration wreaked its inevitable revenge on Afghanistan for blowing up the Twin Towers.

2

Sixty Words

Before exacting revenge, the Bush administration wanted Congressional approval, as under the United States Constitution only Congress can authorise war. So just twenty-four hours after the second plane hit the South Tower, while most people were still trying to digest what had happened, White House lawyer Timothy Flanigan was already sitting at his computer urgently typing up legal justification for action against those responsible.

The last time the US had declared war was in 1991 against Iraq, so he first cut and pasted the wording from the authorisation for that. However, the problem was that this time no one really knew who or where the enemy was, so something wider and more nebulous was needed.

By 13 September Flanigan and his colleagues had come up with the Authorisation for Use of Military Force, or AUMF, for Congress to vote on. At its core was a single sixty-word sentence: ‘That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.’

In other words, this would be war with no restraints of time, location or means.

At 10.16 a.m. on 14 September, the AUMF went to the Senate. The nation wanted action, and all ninety-eight Senators on the floor voted Yes. From there they were bussed straight to Washington’s multi-spired and gargoyled National Cathedral for a noontime prayer meeting called by the White House for the victims of the attacks. It was a highly charged service, with many tears, prayers, a thundering organ and an address by President Bush, followed by the singing of ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’. Members of Congress were then bussed to the House for their vote. One after another called for unity. Four hundred and twenty voted in favour, and just one against. Barbara Lee, a Democratic Congresswoman from California, was as heartbroken as anyone by 9/11 – her Chief of Staff had lost his cousin on one of the flights. But she worried that what she called ‘those sixty horrible words’ could lead to ‘open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target’. So to the outrage of her colleagues, she stood up and voted No. Her voice cracking, she cried as she asked people to ‘think through the implications of our actions today so this does not spiral out of control’. She ended by echoing the words of one of the priests in the cathedral: ‘As we act let us not become the evil we deplore.’