Полная версия

The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

Now, what I trust I shall never give up to another, will be the training of my children … Let the offices, properly belonging to a nurse, be performed by the nurse … Let her have the trouble of the children, their noise, their romping; in short, let the nursery be her place and the children’s place. But I hope I shall never fail to gather my children round me daily, at stated periods, for higher purposes: to instil into them Christian and moral duties; to strive to teach them how best to fulfil life’s obligations. This is a mother’s task … 29

Or, as the novelist Mrs Gaskell had the governess in Ruth (1853) say more succinctly to the children in her care, ‘All that your papa wants always, is that you are quiet and out of the way.’30

Marion Jane Bradley kept a diary of her children’s first years, from 1853 to 1860. In about 1891 she reread it and added a note to the manuscript: ‘I tried to make our children fill their proper subordinate places in the family – Father always to be first considered, their arrangements to be subject to his … Not to seem anxious about their health or to fuss over their comfort and convenience, but to make them feel it was proper for them to give up and be considered secondary. Of course, this is quite old fashioned …’31

It was, truly, quite old-fashioned by the end of the century – for the mother, at least. Fathers remained more distant. Caroline Taylor’s father ‘had a quick temper and we children stood in fear of him. We were never allowed to express our ideas … My father had a knowledge of many subjects and was artistic and musical, but he never conversed on things to his children … Parents always assumed such dignity, and we felt so small.’32 Fifty years before, Mrs Gaskell had reflected the prevailing views in her novels, even while her personal view, in her letters and journal, had long been moving towards precisely that child-centred universe which was the opposite of the children being ‘quiet and out of the way’. Mrs Gaskell was the wife of a Unitarian minister, and the daughter of another, but there was nothing of Evangelical stringency in her attitude to her children. Although she was deeply concerned about their moral welfare, she did not see that children should suffer for it. She was very much of her time in reading numerous advice books, and she carefully considered the instructions they gave. She agreed with those that said that moral fibre was not developed by privation and denial:

I don’t think we should carry out the maxim of never letting a child have anything for crying. If it is to have the object for which it is crying I would give it, directly, giving up any little occupation or purpose of my own, rather than try its patience unnecessarily. But if it is improper for it to obtain the object, I think it right to with-hold the object steadily, however much the little creature may cry … I think it is the duty of every mother to sacrifice a good deal rather than have her child unnecessarily irritated by anything [my italics].33

This was not lip-service: she wrote in her journal, when her daughter Marianne was six months old, ‘If when you [that is, the future, grown-up Marianne] read this, you trace back any evil, or unhappy feeling to my mismanagement in your childhood forgive me, love!’34 This view took concrete form. Earlier, children were to give things up to their elders; now the elders deprived themselves. Because of the cost of Marianne’s schooling, and the larger house they had bought, ‘we aren’t going to furnish the drawing room, & mean to be, and are very œconomical because it seems such an addition to children’s health and happiness to have plenty of room’.35

The interest in children’s happiness was new, but children’s health had always been a concern. Mortality rates for the general population were high, but they were dropping none the less: from 21.8 deaths per 1000 in 1868, to 18.1 in 1888, down to 14.8 in 1908. The young benefited soonest: children first felt the improvements as understanding of disease transmission, a drop in the real price of food, and, most importantly, improved sanitation worked their way through the population.36 (It must be remembered that until this point the most likely time of death was not in old age, but in infancy: as late as 1899, more than 16 per cent of all children did not survive to their first birthday.)37 A child born in the earlier part of the century would probably have watched at least one of its siblings die; a child born in the 1880s would have had fewer siblings, and would also have had less chance of seeing them die.38

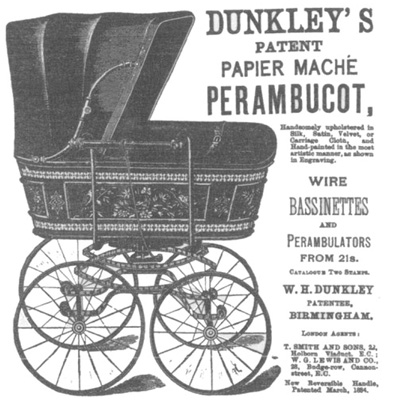

This improvement, together with the increasingly child-centred world they inhabited, made parents ever more solicitous of the health of their children. It was difficult not to worry when a parent could expect to have to deal with scalds, burns, falls, children being dropped by the nursemaid,* swallowed lotions or liniment, swallowed lucifers (matches), clothes catching fire, drowning, stings, overdoses of laudanum, paregoric, Godfrey’s Cordial or Dalby’s Carminative (all four opium derivatives), peas up the nose or in the ears, and swallowed glass or coins.40

Some fears appeared relatively trivial, but uncertain diagnostic techniques meant that many major illnesses could not be identified and separated from minor ones. Seemingly harmless childhood ailments might end in death. Mrs Gaskell reported in her journal on Marianne’s sudden attack of croup: ‘We heard a cough like a dog’s bark … We gave her 24 drops of Ipec: wine, and Sam & Mr Partington both came. They said we had done quite rightly, and ordered her some calomel powders† … [W]e have reason to be most thankful that she is spared to us … Poor little Eddy Deane was taken ill of croup on the same night, and died on the following Monday.’41 Poor little Eddy Deane may very well have had diphtheria: this and croup were often confused.

Even teething, that routine, ordinary, minor fret of babydom, was a major cause of anxiety. Mrs Pedley estimated that 16 per cent of child deaths were teething-related, rather than actually from teething itself. She tried to persuade parents that it was not the malady but the cure that was killing their children. She wrote that, when their babies fretted before their new teeth began to show, worried parents decided that ‘milk no longer agrees with the child’, so they stopped the milk and instead fed the infants on unsuitable foods. This upset their digestions; they were therefore given drugs, most of which contained opium, and, not unnaturally, the babies died in convulsions – more deaths put down to that dread disease, teething.42 Her common sense, however, was drowned out by others who recommended syrup of poppies (Mrs Warren) or purgatives (Dr Chavasse, Mrs Beeton and Mrs Warren) or surgery – lancing the gums (all of the above).

Mrs Beeton listed the symptoms of teething, and they included, apart from the ones we would recognize today – inflamed gums and an increase of saliva – restlessness, irregular bowel movements, fever, disturbed sleep, ‘fretfulness … rolling of the eyes, convulsive startings, labourious breathing’: pretty well everything, in fact. The answer was to give purgatives and a teething ring, put the child in a hot bath, and if necessary lance the gums, ‘which will often snatch the child from the grasp of death … [otherwise] the unrelieved irritation endanger[s] inflammation of the brain, water on the head, rickets, and other lingering affections’. Indeed, Mrs Beeton stressed that rickets and water on the brain were ‘frequent results of dental irritation’.43 Mrs Beeton at least made one concession to the strength of the drugs routinely given to infants: she suggested that, before weaning, medicine could be given via the milk, the mother swallowing the appropriate dose. That was an improvement on many systems, where it was generally expected that the nurse would give the newborn infant a few drops of castor oil as soon as it was born. Mrs Gaskell followed the general trend: Marianne ‘had one violent attack … but we put her directly into warm water, & gave her castor oil, sending at the same time for a medical man, who decided that the inflammatory state of her body was owing to her being on the point of cutting her eye-teeth’.44

‘Convulsions’ were a similarly created illness: death due to convulsions was common, but even at the time many attributed the deaths to the opium-based medicines used as a cure. Mrs Beeton (whose chapter on child-rearing, it should be emphasized, was written for her by a doctor) gave a description of a convulsion: ‘the infant cries out with a quick, short scream, rolls up its eyes, arches its body backwards, its arms become bent and fixed, and the fingers parted; the lips and eyelids assume a dusky leaden colour, while the face remains pale, and the eyes open, glassy, or staring’. This might last a few minutes only, and could surely describe almost any crying child. Yet the worried carers who saw a convulsion in these symptoms were advised to put the baby in a hot bath, give it a teaspoonful of brandy and water and, an hour after the bath, administer a purgative, repeated once or twice every three hours.45 Such ‘spasms’ could also be treated by patent medicines such as J. Collis Browne’s Cholodyne, ‘advertised as a cure for coughs, colds, colic, cramp, spasms, stomach ache, bowel pains, diarrhoea and sleeplessness’. This contained not only opium, but also chloral hydrate and cannabis.46

Children who had once had trouble with fits, or with their teething (and, given these symptoms, all babies did: has anyone ever had a baby who did not at some stage suffer from ‘disturbed sleep’ or ‘fretfulness’?), would shortly have problems caused by the purgatives and opium that had been administered to treat them, starting off a fresh round of medication. Mrs Pedley again tried to calm fears, pointing out that nurses often said children were subject to fits when what they meant was that they had a twitch, or they blinked frequently, or moved their arms and legs after feeding (which she attributed to flatulence).47

Although teething seems a bizarre worry from our perspective, nineteenth-century parents had many more real anxieties than their descendants: by the time they reached the age of five, 35 out of every 45 children had had either smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, typhus or enteric fever (or a combination), all of which could kill.48 Lesser illnesses, such as chickenpox and mumps, were also more dangerous than today, because of the drugs given to treat them. So much of what we take for granted was simply not available, or only barely. A great deal of progress had been made by mid-century: the stethoscope, the thermometer and the percussive technique for listening to the patient’s chest had all been developed; the smallpox vaccine was routinely urged on all parents. Yet what was available and what was commonly used were not necessarily the same thing. Louise Creighton, as late as the early 1880s, was misled when her son complained only mildly of feeling ill: she therefore did nothing for some time. When she finally sent for the doctor, the child was found to have fluid on his lungs; she said later that ‘had I then known the use of the clinical thermometer, which was not yet considered even a desirable instrument … for any mother to use’, she would have recognized the gravity of the illness earlier.49

Even something as basic as a hot-water bottle, to keep a sick child warm, was not easily obtainable. ‘Bottles’ were generally made of stone, and corked at the top. Wriggly fretful children had a nasty tendency to kick the corks out, sending scalding water gushing over themselves. ‘Gutta-percha’ bags were available by mid-century, but they were expensive, and so only for the rich.* The most common method was to heat sand in a pan over the kitchen range and fill cloth bags with it.50

The best solution to illness was to prevent it, all agreed. All also agreed on how this was to be done: a child should lead an orderly, well-regulated daily life, simple in every element. Meals were to be plain and ‘wholesome’ – a wonderful word embodying not only basic nutrition, but also a moral element. In this moral universe food was a danger as well as a benefit: books warned against children being given specific foods – usually strong-tasting ones (especially for girls: such foods were thought to arouse passion, and were troublesome during puberty in particular), though vegetables and fruits could be equally hazardous. It was notable that expensive foods, or ones that tasted good enough to be consumed from desire rather than hunger, were often considered the most unwholesome. Mrs Beeton was not alone in warning of the dangers of fresh bread. Day-old bread was infinitely to be preferred, while ‘Hot rolls, swimming in melted butter … ought to be carefully shunned’ – especially by children, who were to have the most restricted diets. She recommended that suet pastry be made with 5 oz of suet for every pound of flour – although a scant 4 oz would ‘answer very well for children’. Another of her puddings was made with eggs and brandy – unless it was intended for children, when ‘the addition of the latter ingredients will be found quite superfluous’.51 Meat was the basis of children’s diet, as it was of that of their elders, for, as Mrs Pedley noted, ‘The highest form of diet is animal food. It appears that children who, at a befitting age, are judiciously fed on meat, attain a higher standard of moral and intellectual ability than those who live on a different class of food.’52

Breakfast for children in prosperous middle-class houses was almost as Spartan as it was for their lower-middle-class coevals. Gwen Raverat, a granddaughter of Charles Darwin and the daughter of a Cambridge don, throughout her childhood ate toast and butter, and porridge with salt. Twice a week the toast was ‘spread with a thin layer of that dangerous luxury, Jam. But, of course, not butter, too. Butter and Jam on the same bit of bread would have been unheard-of indulgence – a disgraceful orgy.’ She first tasted bacon when she was ten years old and away from home on a visit.53 Louise Creighton first tasted marmalade and jam only after her marriage, when she was in her twenties.54 Compton Mackenzie, the novelist, had a similar prospect in his childhood:

Nor did the diet my old nurse believed to be good for children encourage biliousness, bread and heavily watered milk alternating with porridge and heavily watered milk. Eggs were rigorously forbidden, and the top of one’s father’s or mother’s boiled egg in which we were indulged when we were with them exceeded in luxurious tastiness any caviar or pate de foie gras of the future. No jam was allowed except raspberry and currant, and that was spread so thinly that it seemed merely to add sweetish seeds to the bread.55

The bread and milk (or bread and milk and water) eaten by most lower-middle-class children was not substantially different from this upper-middle-class fare.

Mackenzie was a more rebellious child than Raverat or Creighton, and one day

I thought of a way to exasperate Nanny by telling her that I preferred my bread without butter. I was tired of the way she always transformed butter into scrape, of the way in which, if a dab of butter was happily caught in one of the holes of a slice of … bread … she would excavate it with the knife and turn it into another bit of scrape. I was tired of the way she would mutter that too much butter was not good for me and, as it seemed to me, obviously enjoyed depriving me of it. If I told her that I preferred my bread without butter she would be deprived the pleasure of depriving me.56

No doubt his going without butter was a worry – he was removing the possibility of a lesson in the moral values implicit in food.

Morality was at the heart of home education. When Marianne Gaskell came back from her school in London, her mother was well pleased with what she had learned there: ‘It is delightful to see what good it had done [Marianne], sending her to school … She is such a “law unto herself” now, such a sense of duty, and obeys her sense. For instance, she invariably gave the little ones 2 hours of patient steady teaching in the holidays. If there was to be any long excursion for the day she got up earlier, that was all; & they did too, influenced by her example.’57 The merit of her schooling was not the knowledge she had acquired, but that she had become dutiful.

Most children, boys and girls, were initially taught at home by their mothers. This might begin at a young age, although Mrs Gaskell was concerned not to start Marianne’s schooling too early – ‘We heard the opinion of a medical man latterly, who said that till the age of three years or thereabouts, the brain of an infant appeared constantly to be verging on inflammation, which any little excess of excitement might produce’ – so she waited until after the child’s second birthday. By her third birthday Marianne had begun to read and sew, ‘and makes pretty good progress … I am glad of something that will occupy her, for I have some difficulty in finding her occupation, and she does not set herself to any employment’.58 The expectation that a three-year-old would set herself to specific tasks and that lessons could usefully be learned so young was not uncommon. By his third birthday Marian Jane Bradley’s son Wa was learning to read. Six months later his mother worried that he was very difficult to teach: one day he would read his lessons through with no problem, the next he could not. It took her six weeks to teach him to read ‘cab … which he can’t remember from one day to the next’. But she felt this was her fault – that she was a bad teacher, because ‘It requires more patience than I have’ – not that he was simply too young.59

For, oddly enough, there were few instructions in how to teach small children, despite the preponderance of advice being given in all other areas of life. Mothers were supposed to know simply by virtue of being mothers. Mrs Warren was one of the small number who did discuss this subject. Her book How I Managed My Children on £200 a Year was precisely for mothers who could not expect to be able to afford any outside help. However, although it listed which subjects to teach, she never said how to teach most of these subjects: she assumed that all women knew.*

They did not, of course. Molly Hughes (who later became a teacher) left an account of her education at home – intended to be comic, but hair-raising in the barrenness it revealed. Mid-morning her mother would ‘open an enormous Bible. It was invariably at the Old Testament, and I had to read aloud … No comments were ever made, religious or otherwise, my questions were fobbed off by references to those “old times” or to “bad translations”, and occasionally mother’s pencil, with which she guided me to the words, would travel rapidly over several verses, and I heard a muttered “never mind about that”.’† Then Molly would parse a verse. Her mother painted in watercolour while Molly did ‘a little reading, sewing, writing, or learning by heart’. Geography consisted of looking at an atlas,

but all I can recall of my little geography book is the opening sentence. ‘The Earth is an oblate spheroid’, and the statement that there are seven, or five, oceans. I never could remember which … For scientific notions I had Dr. Brewer’s Guide to Science, in the form of a catechism … It opens firmly thus: ‘Q. What is heat?’ and the A. comes pat: ‘That which produces the sensation of warmth.’ … Some of the information is human and kindly. Thus we have: ‘Q. What should a fearful person do to be secure in a storm? A. Draw his bedstead into the middle of the room, commit himself to the care of God, and go to bed.’* … Mother’s arithmetic was at the level of the White Queen’s, and I believe she was never quite sound about borrowing and paying back, especially if there was a nought or two in the top row … Often when sums were adumbrated I felt a little headachy, and thought I could manage a little drawing and painting instead.

If the weather was good, lessons were cancelled and mother and daughter went for a walk, to the West End to shop or to Hamp-stead to sketch. By the age of twelve Molly had never learned how to add currency – she had never even seen the symbols for pounds, shillings and pence.62

Mothers were the teachers in most houses, of their daughters for their entire school career, and their sons usually to the age of seven. Only the most prosperous could afford governesses. Our impression today is that all middle-class households had governesses for their children, but his impression is based on the aspirational nature of so much writing of the time. There were over 30,000 upper-class families by mid-century, with 25,000 governesses listed in the census of 1851. If we assume only half of these families had young children, that leaves a mere 10,000 governesses to be spread among the families of the 250,000 professional men listed in the 1851 census. Again, assume only half had young children. That is still only one governess for every twelve families, and that is not counting the many tens of thousands of clergy, prosperous merchants, bankers, businessmen, factory-owners, all of whom would have had equal call on this precious commodity.

Even where governesses were employed, teaching was not necessary any better. As Gwen Raverat said of her governess: ‘They were all kind, good, dull women; but even interesting lessons can be made incredibly stupid, when they are taught by people who are bored to death with them, and who do not care for the art of teaching either.’63 Charles Dickens’s portrait of Gradgrind, with his love of Facts, was not only a comic fiction: literature both high and low reflected this idea of education as chunks of information. Charlotte M. Yonge gave a vivid picture in The Daisy Chain (1856). There the children had a visiting French master who knew the language well and could tell Ethel, the clever child, when she had gone wrong, but he could not explain why. Ethel

did not like to … have no security against future errors; while he thought her a troublesome pupil, and was put out by her questions … Miss Winter [the governess] … summoned her to an examination such as the governess was very fond of and often practised. Ethel thought it useless … It was of this kind: –

What is the date of the invention of paper?

What is the latitude and longitude of Otaheite?

What are the component parts of brass?

Whence is cochineal imported?64

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1857) spoke the same language as Miss Winter:

I learnt a little algebra, a little

Of the mathematics, – brushed with extreme flounce

The circle of the sciences …

I learnt the royal genealogies

Of Oviedo, the internal laws

Of the Burmese empire, – by how many feet

Mount Chimaborazo outsoars Teneriffe.

What navigable river joins itself

To Lara, and what census of the year five

Was taken at Klagenfurt, – because she liked

A general insight into useful facts.65

The Daisy Chain and Aurora Leigh both appeared in the mid-1850s. Many girls were still being taught the same things in the same way at the end of the century. Eleanor Farjeon, the children’s writer, remembered her schoolroom days in the 1890s:

Miss Milton taught us Spelling … and the Capitals of Europe, and Tables, and Dates. There was no magic in these things as she taught them …

‘What is the date of the Constitutions of Clarendon?’

‘Eleven-hundred-and-sixty-four.’

‘Quite right. You know that now.’

‘Yes, Miss Milton.’

But what exactly did I know, when I knew that? … I didn’t know what ‘Constitutions of Clarendon’ was. Was it to do with somebody’s health? Who was Clarendon? Or perhaps with the way red wine was made … What was Clarendon? Miss Milton never told me, and I never asked.66

Eleanor Farjeon did not come from a philistine background: her father was a successful author. His sons went to school, while his daughter was doomed to Miss Milton not because he was unkind, but because, as Louise Creighton said a quarter of a century before, ‘I do not think that such an idea was ever entertained.’67