Полная версия

The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

THE VICTORIAN HOUSE

Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

JUDITH FLANDERS

DEDICATION

For my mother, Kappy Flanders

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION: House and Home

1 The Bedroom

2 The Nursery

3 The Kitchen

4 The Scullery

5 The Drawing Room

6 The Parlour

7 The Dining Room

8 The Morning Room

9 The Bathroom and Lavatory

10 The Sickroom

11 The Street

APPENDICES

1 Mourning Clothes for Women

2 A Quick Guide to Books and Authors

3 Currency

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

LIST OF INTEGRATED IMAGES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NOTES

PRAISE

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

HOUSE AND HOME

IN 1909 H.G.WELLS WROTE, in a passage from his novel Tono-Bungay, of Edward Ponderevo, a purveyor of patent medicines and

terror of eminent historians. ‘Don’t want your drum and trumpet history – no fear … Don’t want to know who was who’s mistress, and why so-and-so devastated such a province; that’s bound to be all lies and upsy-down anyhow. Not my affair … What I want to know is, in the middle ages Did they Do Anything for Housemaid’s Knee? What did they put in their hot baths after jousting, and was the Black Prince – you know the Black Prince – was he enamelled or painted, or what? I think myself, black-leaded – very likely – like pipeclay – but did they use blacking so early?’1

It is a comic view of history. Or is it? History is usually read either from the top down – kings and queens, the leaders and their followers – or from the bottom up – the common people and their lives. Political history and social history, however, both encompass the one thing we all share – that at the end of the day, after ruling empires or finishing the late shift in a factory, we all go back to our homes. Different as those homes are, how we live at home, where we live, what we do all day when we’re not doing whatever it is that history is recording – these are some of the most telling things about any age, any people. Mme Merle in Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady (1881) notes how ‘one’s house, one’s furniture, one’s garments, the books one reads, the company one keeps – all these things are expressive’.2

This is true of any age, but the Victorians brought the idea of home to the fore in a way that was new. As the Victorians saw ‘home’ as omnipresent, it has seemed to me useful to rely on the same sources that surrounded them and formed their notions of what a home should be – magazines, advertisements, manuals and fiction. In describing people’s daily lives, I look first at what theory prescribed and described in these print sources, and then try to discover the reality in reportage, diaries, letters and journals. Novels are used frequently, as fiction straddles the two camps in that it both set standards for ‘proper’, or ‘normal’, behaviour in theory and also described this behaviour in actuality. In using fiction as a source for how people actually behaved I have primarily relied on novels for information that the authors regarded as background material rather than key plot devices, and have always balanced them with other, more conventional, documentary sources for corroboration.*

By the mid nineteenth century magazine titles epitomized the centrality of the home in Victorian life, boasting the growing middle classes’ new allegiance: The Home Circle, The Home Companion, The Home Friend, Home Thoughts, The Home Magazine, Family Economist, Family Record, Family Friend, Family Treasure, Family Prize Magazine and Household Miscellany, Family Paper and Family Mirror.3 They were not alone in their focus. Services were provided by ‘Family Drapers’, ‘Family Butchers’, even a ‘Family Mourning Warehouse’.4 As the Industrial Revolution appeared to have taken over every aspect of working life, so the family, and by extension the house, expanded in tandem to act as an emotional counterweight. The Victorians found it useful to separate their world into a public sphere, of work and trade, and a private sphere, of home life and domesticity. The Victorian house became defined as a refuge, a place apart from the sordid aspects of commercial life, with different morals, different rules, different guidelines to protect the soul from being consumed by commerce. Or so it seemed.

Domesticity began to acquire a new importance in the late eighteenth century, and in half a century it had made such strides that the house as shelter from outside forces was regarded as the norm. The eighteenth century had been the age of the club and the coffee house for those who could afford them, the gin shop and street gatherings for those who could not. Male companionship in leisure time was the norm for men. Now women at home were looked at in a different light: they became, as John Ruskin was later to describe the home, the focus of existence, the source of refuge and retreat, but also of strength and renewal.

It was not one thing alone that created this powerful urge to domesticity, but a combination: the rise of the Evangelical movement and, almost simultaneously, of Methodism and other dissenting sects; improvements in mortality figures; and the creation of the factory as a place of employment. It is for these reasons that I have chosen to focus primarily on the period 1850 to 1890 – from the rise of the High Victorian era to the end of the recession that marked the 1870s and 1880s and led to the long Edwardian summer. These forty years were a dynamic era of much change. Yet it seems that this very dynamism led people to try to create a still centre in their homes, where things changed as little as possible. In many areas this period can be discussed as a unity, because that is how its participants hoped to see it: as a stable period, although the reality of rapid technological change could make this desire for stasis seem almost ludicrous. These conflicting desires are, I hope, represented with equal weight here.

One of the first forces of change came with the wave of Evangelical fervour that swept the country in the early part of the century. Evangelicals hoped to find a Christian path in all their actions, including the details of daily life: a true Christian must ensure that the family operated in a milieu that could promote good relations between family members and between the family members and their servants, and between the family and the outside world. The home was a microcosm of the ideal society, with love and charity replacing the commerce and capitalism of the outside world. This dichotomy allowed men to pursue business in a suitably capitalist – perhaps even ruthless – fashion, because they knew they could refresh the inner man by returning at the end of the day to an atmosphere of harmony, from which competition was banished. This idea was so useful that it was internalized by many who shared no religious beliefs with the Evangelicals, and it rapidly became a secular norm.5

At the same time advances in technology were changing more traditional aspects of home life. With improved sanitation and hygiene, child mortality was falling. The middle classes had more disposable income, and thus anxiety about the fundamentals of life – enough food, affordable light and heat – diminished. With the increase in child survival rates came coincidentally the gradual phasing out of the apprenticeship system for middle-class professions such as medicine and the law, which meant that for the first time many parents could watch their children reach adulthood in their own homes. The Romantic movement’s creation of the cult of innocence promoted an idealized view of childhood, and produced what has sometimes been referred to as ‘the cult of the child’: the child-centred home was developing.

That work was moving outside the home was the third essential factor in the creation of nineteenth-century domesticity. Previously, many of the working classes had found occupation in piecework, which was produced at home. With the coming of the factories, work moved to a place of regimentation and timekeeping. The middle classes too had been used to work at home: at the lower end of the scale, shopkeepers lived above their shops; slightly higher up, wholesalers lived above their warehouses. Doctors and lawyers had consulting rooms at home, as did many other professionals. Women who had helped their husbands with their work – serving in the shop, doing the accounts, keeping track of correspondence or clients – were now physically separated from their husbands’ labour and became solely housekeepers. Slowly the cities became segregated: those who could afford it no longer lived near their work. An early example was the suburb of Edgbaston, on the edge of Birmingham, planned in the early part of the century by Lord Calthorpe to provide ‘genteel homes for the middle classes’, and proudly known as the ‘Belgravia of Birmingham’. Its homes were for the families who owned and ran the industries on which the town thrived – but who did not want to live near them. The leases for houses in Edgbaston were clear: no retail premises were permitted, nor was professional work to be undertaken in these houses. Edgbaston was the first residential area that assumed that people wanted to live and work in different locations.6 Over the century this same transformation occurred across the country. In London the City became a place of work, the West End a place of residence; gradually, as the West End acquired a work character too, the suburbs became the residential areas of choice.

Charles Dickens, the great chronicler of domestic life in all its shades, was well aware of the perils of promiscuous mixing of home and work. In Dombey and Son (1848) Mr Dombey, the head of a great shipping company, is unable to leave his business behind him when he returns home. His only thoughts are of ‘Dombey and Son’ and, by allowing his work life to contaminate his family life, he destroys the latter – and, by extension, the former. In Great Expectations (1860–61) the law clerk Wemmick bases his life entirely on the separation of work and home: ‘the office is one thing, and private life is another. When I go into the office, I leave the Castle [his house in the suburbs] behind me, and when I come into the Castle, I leave the office behind me … I don’t wish it professionally spoken about.’7 That the fictional Mark Rutherford, nearing the end of the century, thought no differently confirmed that this attitude was not simply a jeu d’esprit of Dickens. William Hale White (1831–1913) wrote a series of supposedly autobiographical books under the name Mark Rutherford. White was a dissenter who had trained for the ministry before he lost his faith; he then became a civil servant at the Admiralty. His alter ego, Rutherford, was also a minister who lost his faith. About his private life Rutherford wrote that at the office ‘Nobody knew anything about me, whether I was married or single, where I lived, or what I thought upon a single subject of any importance. I cut off my office life in this way from my home life so completely that I was two selves, and my true self was not stained by contact with my other self. It was a comfort to me to think the moment the clock struck seven that my second self died.’8

That ‘true self’ was the real man, on view only at home. Ruskin’s father wrote, ‘Oh! how dull and dreary is the best society I fall into compared with the circle of my own Fire Side with my Love sitting opposite irradiating all around her, and my most extraordinary boy.’9 With this the good Victorian was supposed to – and often did – rest content For, as the clerk Charles Pooter put it so eloquently in The Diary of a Nobody (1892), George and Weedon Grossmith’s comic masterpiece of genteel English anxiety. ‘After my work in the City, I like to be at home. What’s the good of a home, if you are never in it?’10 Mr Pooter’s ideal of the good life, recounted in diary form, centred on his dream house in the suburbs.

In continental Europe the opposite was happening. The Goncourt brothers wrote in their diary in 1860, ‘One can see women, children, husbands and wives, whole families in the café. The home life is dying. Life is threatening to become public.’11 Europeans socialized in public: in restaurants (a French invention), in cafes (perfected by the Viennese), in the streets (Italians still perform the passeggiata in the evenings). But the English became ever more inward-turning. The small wrought-iron balconies that had decorated so many Georgian houses vanished, seemingly overnight. Thick curtains replaced the airy eighteenth-century windows, as much to block out passers-by who might look in as to prevent the damage wrought by sun and pollution.

For the house was not a static object in which changing values were expressed. In the eighteenth century and before, rooms had been multi-purpose, and furniture had been moved and adapted to serve the different functions each room acquired in turn. (The French for ‘building’ and ‘furniture’ are a legacy of this: immeuble is a building or, literally, ‘immovable’, and meuble, furniture, is literally, ‘movable’.) Now, in the nineteenth century, segregation of each function of the house became as important as separation of home and work: both home and work contained an aspect of both a public and a private sphere. The house was the physical demarcation between home and work, and in turn each room was the physical demarcation of many further segregations: of hierarchy (rooms used for visitors being of higher status than family-only rooms); of function (display rating more highly than utility); and of further divisions of public and private (so that rooms which were used for both public and private functions, such as the dining room, changed in importance with their use). ‘Subdivision, classification, and elaboration, are certainly distinguishing characteristics of the present era of civilisation,’ thought George Augustus Sala in 1859.*12

In the eighteenth century and before, servants and apprentices had often slept in the same rooms as family members, who themselves were not separated in sleeping apartments by gender or age. Gradually the Victorian house divided rooms that were designed for receiving outsiders – the dining room, the drawing room, the morning room – from rooms that were for family members only – bedrooms, the study – and, further, from rooms that were for servants only – the kitchen, the scullery, servants’ bedrooms. Parents no longer expected to sleep with their babies, and children no longer slept together – boys and girls needed separate rooms, at the very least, and it was preferable that younger children be separated from older ones. The additional rooms required were of necessity smaller, and higher up, but the extra privacy made them desirable. Even those forced to live in houses small enough to require multi-purpose rooms felt that ‘Nothing conduces so much to the degradation of a man and a woman in the opinion of each other’ than having to perform their separate functions together in the same room. This was written by Francis Place, a radical tailor. When he managed to reach a financial level where he and his wife could afford to live with enough space so that they could work separately, ‘It was advantageous … in its moral effects. Attendance on the child was not as it had been always, in my presence. I was shut out from seeing the fire lighted, the room washed and cleaned, and the cloathes [sic] washed and ironed, as well as the cooking.’13

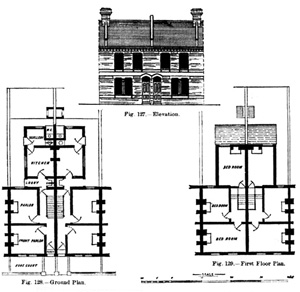

Plans for terraced houses for the lower middle classes, c. 1870s. Note there is no bathroom, and the lavatory is still reached from the outside. The kitchen is spacious, however, with a separate larder (opposite the lobby), and a scullery with a copper. These houses rented for about £30 a year.

In theory, home was the private space of families. In practice – unacknowledged – houses were another aspect of public life. ‘Home’ was created by family life, but the house itself was inextricably linked with worldly success: the size of the house, how it was furnished, where it was located, all were indicative of the family that lived privately within. His family’s mode of private living was yet a further reflection of a man’s public success in the world. Income was no longer derived primarily from land: the professional and merchant classes, as a group, were now substantially wealthier than they had ever been, and they imitated the style of their social superiors in order to live up to their new status: household possessions, types of furnishing, elegance of entertaining and dress, all these ‘home’ aspects were a reflection of success at work. Therefore the public rooms, as an expression of achievement and worldly success, often took up far more of the space in the house than we today consider convenient. The money available to spend on household goods was lavished first on those rooms that were on public display. The economist Thorstein Veblen noted the phenomenon in the US, but it holds good for Britain too: ‘Through this discrimination in favour of visible consumption it has come about that the domestic life of most classes is relatively shabby, as compared with the éclat of that overt portion of their life that is carried on before the eyes of observers.’14

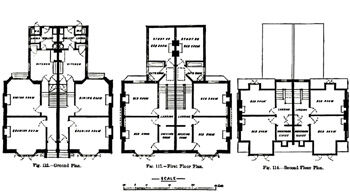

Semi-detached houses Ealing, built for the prosperous middle classes, with five bedrooms, a dressing room and a bathroom. As well as a larder, there is a storeroom opening off the kitchen. These houses rented for about £50 a year.

Dickens devoted a great deal of attention to the different types of home that were available to his characters. His biographer and friend John Forster remembered, ‘If it is the property of a domestic nature to be personally interested in every detail, the smallest as the greatest of the four walls within which one lives, then no man had it so essentially as Dickens, no man was so inclined naturally to derive his happiness from home concerns.’15 The novelist gave no less attention to his characters’ home concerns. There was, first, the ideal, which he elaborated in his ‘Sketches of Young Couples’:

Before marriage and afterwards, let [couples] learn to centre all their hopes of real and lasting happiness in their own fireside; let them cherish the faith that in home … lies the only true source of domestic felicity; let them believe that round the household gods, contentment and tranquillity cluster in their gentlest and most graceful forms; and that many weary hunters of happiness through the noisy world, have learnt this truth too late, and found a cheerful spirit and a quiet mind only at home at last.16

That even Dickens became entangled in a circular notion that defined itself by referring to itself – that the domestic realm was the place where one found domestic happiness – that even he could not (or found no need to) explain this idea better, is surely telling. Domesticity was so much a part of the spirit of the times that simply to say ‘it is what it is’ was adequate.

Dickens also used the language of domesticity both to create and to mock the role of women at home. In Edwin Drood (1870) Rosa worked at her sewing while her chaperone, Miss Twinkleton, read aloud. Miss Twinkleton did not read ‘fairly’, however:

She … was guilty of … glaring pious frauds. As an instance in point, take the glowing passage: ‘Ever dearest and best adored, said Edward, clasping the dear head to his breast, and drawing the silken hair through his caressing fingers … let us fly from the unsympathetic world and the sterile coldness of the stony-hearted, to the rich warm Paradise of Trust and Love.’ Miss Twinkleton’s fraudulent version tamely ran thus: ‘Ever engaged to me with the consent of our parents on both sides, and the approbation of the silver-haired rector of the district, said Edward, respectfully raising to his lips the taper fingers so skilful in embroidery, tambour, crochet, and other truly feminine arts; let me call on thy papa … and propose a suburban establishment, lowly it may be, but within our means, where he will be always welcome as an evening guest, and where every arrangement shall invest economy and the constant interchange of scholastic acquirements with the attributes of the ministering angel to domestic bliss.’17

However comic the intent in the passage above, ‘the ministering angel to domestic bliss’ was what both Dickens and the majority of the population believed women should be. Evangelical ideas had linked the idea of womanliness to women carrying out their biological destiny – to being wives and mothers. That was their job, and to expect to have any other job was a rejection of their God-given place, despite the fact that, by the second half of the century, 25 per cent of women had paying work of necessity, in order to survive. Most of the remaining 75 per cent worked at home. As will be seen, among the middle classes only the very top levels could afford the number of servants that made work for housebound women unnecessary. In spite of this uncomfortable reality, the hierarchy of authority was undisputed: God gave his authority to man, man ruled woman, and woman ruled the household, both children and servants, through the delegated authority she received from man. One of the many books of advice and counsel on how to be better wives and mothers reminded women, ‘The most important person in the household is the head of the family – the father … Though he may, perhaps, spend less time at home than any other member of the family – though he has scarcely a voice in family affairs – though the whole household machinery seems to go on without the assistance of his management – still it does depend entirely on that active brain and those busy hands.’18 Sarah Stickney Ellis, an extremely popular writer for women, was even more blunt: ‘It is quite possible you may have more talent [than your husband], with higher attainments, and you may also have been generally more admired; but this has nothing whatever to do with your position as a woman, which is, and must be, inferior to his as a man.’19 George Gissing explored this view in his novel The Odd Women (1893). The ominously named Edmund Widdowson ‘regarded [women] as born to perpetual pupilage. Not that their inclinations were necessarily wanton; they were simply incapable of attaining maturity, remained throughout their life imperfect beings, at the mercy of craft, ever liable to be misled by childish misconceptions.’20

That this was generally believed, and not simply advice-book cant, can be seen in numerous letters and diaries. Marion Jane Bradley, the wife of a master at Rugby School, wrote in her diary, ‘How important a work is mine. To be a cheerful, loving wife, and forbearing, fond, wise, thoughtful mother, striving ever against self-indulgence and irritability, which often sorely beset me. As a mistress, to be kind, gentle, thoughtful both for the bodies and souls of my servants. As a visitor of the poor to spare myself no trouble so as to relieve wisely and well.’21 She saw herself as an entirely reactive character without the husband, children, servants and poor, she had no role. Women were there for encouragement, to help men when they were depressed – in New Grub Street (1891), George Gissing’s novel of literary life on the edge of poverty, the wife and husband quarrel. Amy says, ‘Edwin, let me tell you something. You are getting too fond of speaking in a discouraging way …’ He responds, ‘… granted that … I easily fall into gloomy ways of talk, what is Amy here for?’22