Полная версия

The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

Men set the agenda, while it was up to women to carry it through. Men are present often by their absence in the pages that follow, despite the fact that men were undoubtedly the fount from which women’s possibilities grew. It was on marriage that women achieved that great necessity, a home of their own. It is clear, however, that men were barely concerned with the running of the house: ‘Though he may, perhaps, spend less time at home than any other member of the family – though he has scarcely a voice in family affairs – though the whole household machinery seems to go on without the assistance of his management …’ Men were the source of funds, but it was women who judged other women, women who (to the rules of men) made the decisions that activated and continued the social circles that made up the lives of most families. Although there are several fine books on the role of men at home,23 this will not be another of them.*

Most contemporaries accepted Ruskin’s views on women and home – home was not a place, but a projection of the feminine, an encircling, encouraging, comforting aura that was there to protect a husband and children from the harshness of the world: ‘wherever a true wife comes’, Ruskin wrote, ‘this home is always around her’.24 Creating a home was the role assigned to women, but it was not something over which they could exercise free will. What made a good home was carefully laid down:

Not only must the house be neat and clean, but it must be so ordered as to suit the tastes of all … Not only must a constant system of activity be established, but peace must be preserved, or happiness will be destroyed. Not only must elegance be called in, to adorn and beautify the whole, but strict integrity must be maintained by the minutest calculation as to lawful means, and self, and self-gratification, must be made the yielding point in every disputed case. Not only must an appearance of outward order and comfort be kept up, but around every domestic scene there must be a strong wall of confidence, which no internal suspicion can undermine, no external enemy break through.25

No small task, and success or failure would be laid entirely at the door of Mrs Ellis’s ‘Women of England’.

Coventry Patmore’s best-selling The Angel in the House (1854–63) portrayed women as passive and self-abnegating, while his men were driven by a desire to achieve. Housework was ideal for women, as its unending, non-linear nature gave it a more virtuous air than something which was focused, and could be achieved and have a result. Gissing allowed Edward Widdowson a certain naivety in order that the novelist might express a more cynical view: ‘Women were very like children; it was rather a task to amuse them and to keep them out of mischief. Therefore the blessedness of household toil, in especial the blessedness of child-bearing and all that followed.’26 Women’s household achievements had more to them than simple cleanliness: Arnold Bennett, in The Old Wives’ Tale (1908), set in the Potteries in the second half of the century, shows a drunken woman, about whom the narrator reflects in horror: ‘A wife and mother! The lady of a house! The centre of order! The fount of healing! The balm for worry and the refuge of distress!… She was the dishonour of her sex, her situation, and her years.’27 It was in failing in these roles that she was repulsive, not in the act of drunkenness itself, which Bennett shows several times in men with condemnation but not with disgust.

Housekeeping was a source of strength for women, through which they could somehow mystically influence their husbands. In Dickens’s Bleak House (1852–3) the Jellyby home is going to ruin because Mrs Jellyby is more interested in her charitable works in Africa than in her own family. And it is not only the housekeeping that is affected by her absence of purpose at home: her daughter Caddy warns that ‘Pa will be bankrupt before long … There’ll be nobody but Ma to thank for it … When all our tradesmen send into our house any stuff they like, and the servants do what they like with it, and I have no time to improve things if I knew how, and Ma don’t care about anything, I should like to make out how Pa is to weather the storm.’28 Mr Jellyby’s impending bankruptcy is to be laid entirely at the door of his wife’s bad housekeeping.

Good housekeeping improved more than just the house. Caddy Jellyby is teaching herself how to run a house: ‘I can make little puddings too; and I know how to buy neck of mutton, and tea, and sugar, and butter, and a good many housekeeping things. I am not clever at my needle yet … but perhaps I shall improve, and since I have been engaged … and have been doing all this, I have felt better-tempered, I hope, and more forgiving.’29 She has become a better person through good housekeeping. The virtues that orderly housekeeping could bring about were almost unending. When in 1860 the child Francis Kent was murdered in a middle-class family home, the shock was not only at the brutal murder, but also because ‘It is in this case … almost certain that some member of a respectable household – such as your’s reader or our’s [sic] – which goes to church with regularity, has family prayers, and whose bills are punctually settled, has murdered an unoffending child.’30 Note the ingredients that make up a respectable household: church, family, prayer and prompt bill-paying.

The well-kept house directed men as well as women towards the path of virtue, while the opposite led them irretrievably astray. Most of the published warnings were for the working classes, who were always considered more likely to err:

The man who goes home from his work on a Saturday only to find his house in disorder, with every article of furniture out of its place, the floor unwashed or sloppy from uncompleted washing, his wife slovenly, his children untidy, his dinner not yet ready or spoilt in the cooking, is much more likely to go ‘on the spree’ than the man who finds his house in order, the furniture glistening from the recent polishing, the burnished steel fire-irons looking doubly resplendent from the bright glow of the cheerful fire, his well-cooked dinner ready laid on a snowy cloth, and his wife and children tidy and cheerful … the man who has a clever and industrious wife, whose home is so managed that it is always cosy and cheerful when he is in it, finds there a charm, which, if he is endowed with an ordinary share of manliness and self-respect, will render him insensible to the allurements of meretricious amusements.31

Working-class men who were not properly looked after by their wives retired to the pub. And, if their houses were not kept to a suitable level of comfort, even sober middle-class men were expected to vanish, although more likely to their clubs than to pubs. In East Lynne, Mrs Henry Wood’s wonderful 1861 melodrama of love betrayed, the second Mrs Carlyle, wife to a successful lawyer, is quite sure that if children are too much in evidence at home, ‘The discipline of that house soon becomes broken. The children run wild; the husband is sick of it, and seeks peace and solace elsewhere.’ She does not blame the husband, but the wife who is operating ‘a most mistaken and pernicious system’.32 Advice books echoed Mrs Carlyle: ‘Men are free to come and go as they list, they have so much liberty of action, so many out-door resources if wearied with in-doors, that it is a good policy … to make home attractive as well as comfortable.’33

The attractive, tastefully appointed house was a sign of respectability. Taste was not something personal; instead it was something sanctioned by society. Taste, as agreed by society, had moral values, and therefore adherence to what was considered at any one time to be good taste was a virtue, while ignoring the taste of the period was a sign of something very wrong indeed.* Conformity, conventionality, was morality. Christopher Dresser, a designer and influential writer on decorative arts, promised that ‘Art can lend to an apartment not only beauty, but such refinement as will cause it to have an elevating influence on those who dwell in it.’35 The house, and its decoration, was an expression of the morality that resided within. Mrs Panton, a prolific advice-book writer, was ‘quite certain that when people care for their homes, they are much better in every way, mentally and morally, than those who only regard them as places to eat and sleep in … while if a house is made beautiful, those who are to dwell in it will … cultivate home virtue’.36

What the house contained, how it was laid out, what the occupations of its inhabitants were, what the wife did all day: these were the details from which society built up its picture of the family and the home, and it is precisely these details that I am concerned with in this book. I have shaped the book not along a floor-plan, but along a life-span. I begin in the bedroom, with childbirth, moving on to the nursery, and children’s lives. Gradually I progress to the public rooms of the house and with those rooms the adult public world, marriage and social life, before moving on, via the sickroom, to illness and death. Thus a single house contains a multiplicity of lives.

The nineteenth century was the century of urbanization. In 1801 only 20 per cent of the population of Great Britain lived in cities. By the death of Queen Victoria, in 1901, that figure had risen to nearly 80 per cent. Of those cities, the greatest was undoubtedly London. London was not just the biggest city in Britain; it was the biggest city in the world: in 1890 it had 4.2 million people, compared to 2.7 million in New York, its nearest rival, and just 2.5 million in Paris.

It was not capital cities alone that were drawing in the rural population. Until 1811, only London had a population of more than 100,000 people in Britain. By the beginning of Victoria’s reign, in 1837, there were another five such cities, and by the time of her death there were forty-nine. ‘The Victorians, indeed, created a new civilization, “so thoroughly of the town” that it has been said to be the first of its kind in human history.’37

To house the numbers of newly urbanized people was a challenge without precedent, and it was met in a unique way. As Continental cities (and New York) grew, apartment blocks sprang up: communal living became the norm. Apart from in Edinburgh, this was rejected in an unconscious yet unanimous way across the British Isles. Instead, a frenzy of house-building began. One-third of the houses in Britain today were built before the First World War, and most of these are Victorian. In a period of less than seventy-five years, over 6 million houses were built, and the majority still stand and function as homes today. Despite the speed with which this massive work went on, despite the often sub-standard building practices, the twenty-first-century cities of Britain are covered with terraced housing built by the Victorians. This once-unique solution to a sudden problem is now so ubiquitous that we no longer regard our terraced houses as anything except the epitome of ‘home’. Yet they were a pragmatic solution to a problem that arose from major upheavals in society.

The fact that the solution was pragmatic does not mean that it did not also meet an almost visceral need. The French philosopher Hippolyte Taine wrote of his time in England, ‘it is the Englishman who wishes to be by himself in his staircase as in his room, who could not endure the promiscuous existence of our huge Parisian cages, and who, even in London, plans his house as a small castle, independent and enclosed … he is exacting in the matter of condition and comfort, and separates his life from that of his inferiors’.38

Thus wrote an outsider looking in. From the inside, the Registrar General pondered on the meaning of ‘house’ and ‘home’ revealed by the census of 1851: ‘It is so much of the order of nature that a family should live in a separate house, that “house” is often used for “family” in many languages, and this isolation of families, in separate houses, it has been asserted, is carried to a greater extent in England than it is elsewhere.’ He quoted a German naturalist:

English dwelling-houses … stand in close connection with that long-cherished principle of separation and retirement, lying as the very foundation of the national character … the Englishman still perseveres … a certain separation of himself from others, which constitutes the very foundation of his freedom … It is that that gives the Englishman that proud feeling of personal independence, which is stereotyped in the phrase, ‘Every man’s house is his castle.’ This is … an expression which cannot be used in Germany and France, where ten or fifteen families often live together in the same large house.

The German naturalist then went on to describe how the English lived – something the English themselves in general never bothered to think of, so natural was it to them:

In English towns or villages, therefore, one always meets either with small detached houses merely suited to one family, or apparently large buildings extending to the length of half a street, sometimes adorned like palaces on the exterior, but separated by partition walls internally, and thus divided into a great number of small high houses, for the most part three windows broad, within which, and on the various stories, the rooms are divided according to the wants and convenience of the family; in short, therefore, it may be properly said, that the English divide their edifices perpendicularly into houses – whereas we Germans divide them horizontally into floors. In England, every man is master of his hall, stairs, and chambers – whereas we are obliged to use the two first in common with others.

The Registrar General concluded, ‘The possession of an entire house is, it is true, strongly desired by every Englishman; for it throws a sharp, well-defined circle round his family and hearth – the shrine of his sorrows, joys, and meditations. This feeling, as it is natural, is universal, but it is stronger in England than it is on the Continent.’39

Although the German he quoted indicated clearly how foreign he found the idea to be, to the Registrar General the terraced house was so normal that he could not bring himself to believe in its uniqueness, and the most he could admit to was that it was both ‘universal’ and ‘stronger in England’. However, both he and his German source agreed that ‘An Englishman’s home is his castle.’ This phrase had first been used in the seventeenth century by the jurist Sir Edward Coke to describe a legal and political situation. By the Victorian era it had become a social description.40

Dickens found great comic potential in this contemporary preoccupation. In 1841, in The Old Curiosity Shop, he had mocked the urge for suburban retreat; twenty years later, in Great Expectations (1860–61), his affection for the idea of sanctuary from the outside world was so strong in every phrase of his description of the clerk Wemmick’s home in the suburbs that it was clear he now sympathized:

Wemmick’s house was a little wooden cottage in the midst of plots of garden, and the top of it was cut out and painted like a battery mounted with guns …

I think it was the smallest house I ever saw; with the queerest gothic windows (by far the greater part of them sham), and a gothic door, almost too small to get in at.

‘That’s a real flagstaff, you see,’ said Wemmick, ‘and on Sundays I run up a real flag. Then look here. After I have crossed this bridge, I hoist it up – so – and cut off the communication.’

The bridge was a plank, and it crossed a chasm about four feet wide and two deep. But it was very pleasant to see the pride with which he hoisted it up and made it fast; smiling as he did so, with a relish and not merely mechanically.

‘At nine o’clock every night, Greenwich time,’* said Wemmick, ‘the gun fires. There he is you see! And when you hear him go, I think you’ll say he’s a Stinger.’

The piece of ordnance referred to, was mounted in a separate fortress, constructed of lattice-work. It was protected from the weather by an ingenious little tarpaulin contrivance in the nature of an umbrella.41

Houses, then, were something that philosophers, civil servants and novelists all thought important enough to discuss at length. They were status symbols, but the status they gave was markedly different from our own preoccupations. Today in the United Kingdom we are concerned with property ownership. The Victorians as a whole found ownership of less importance than occupancy and display. Although no firm figures exist, most historians estimate that a bare 10 per cent of the population owned their own homes;42 the rest rented: the poorest paying weekly, the prosperous middle classes taking renewable seven-year leases. This allowed families to move promptly and easily as their circumstances changed: either with the increase and decrease of the size of the family, or to larger or smaller houses in better or less good neighbourhoods as income fluctuated. In one area of Liverpool, it is estimated, 82 per cent of the population moved within ten years, 40 per cent moving within twelve months.43 Mrs Panton, the Mrs Beeton of home decoration, saw this constant coming and going as sensible: she could not quite allow herself to suggest that family incomes might ever be imperilled, but ‘neighbourhoods alter so rapidly in character and in personelle likewise, that I cannot blame young folk for refusing more than a three years’ agreement, or at the most a seven years’ lease’.*45

The type of neighbourhood one lived in was as important as the type of house. It was important to have neighbours of equal standing, so that a social homogeneity was achieved. Thus shops and other services were confined where possible to busy main streets, and the more desirable houses were tucked in on quiet streets behind – the opposite of continental Europe, where the bigger, more imposing houses were to be found on the wider, more imposing streets. William Morris, after a trip to an outlying suburb, despaired: ‘villas and nothing but villas save a chemist’s shop and a dry public house near the station: no sign of any common people, or anything but gentlemen and servants – a beastly place to live in’.46

The notion of home was structured in part by the importance given to privacy and retreat, and in part by the idea that conformity to social norms was an outward indication of morality. This ensured that display was vested in the choice of neighbourhood, and then in interior decoration. The outside, by contrast, was as unrevealing as the stark facade of an Arab house, turned inwards upon its courtyard. Most thought this a virtue: in 1815 Walter Scott had Guy Mannering say about a house auction, ‘It is disgusting to see the scenes of domestic society and seclusion thrown open to the gaze of the curious and the vulgar.’47 As late as 1866–7 Anthony Trollope in The Last Chronicle of Barset described the same feeling. Archdeacon Grantly is disappointed when his son Major Grantly wants to marry a disgraced curate’s daughter, but he is horrified when the Major puts his possessions up for auction to finance the marriage when his father cuts off his allowance.48 That the masses should see into a gentleman’s private affairs was not to be borne.

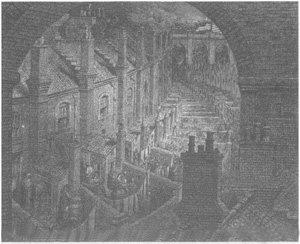

Gustave Doré produced a series of illustrations of London life. Here the backs of suburban London houses are seen from a railway cutting in a typical view of the way these brick tentacles were spreading ever-outwards into the countryside. Note the rear extensions, which house sculleries, with their small chimneys for the coppers.

One rung down the social scale from Archdeacon Grantly and his kind were the endless rows of brick houses that stretched out to the horizon with deadening sameness. Conan Doyle situated his hero in Baker Street, right on the edge of the new developments, and he could not help describing the ‘Long lines of dull brick houses [which] were only relieved by the coarse glare and tawdry brilliancy of public-houses at the corner. Then came rows of two-storeyed villas, each with a fronting of miniature garden, and then again interminable lines of new staring brick buildings – the monster tentacles which the giant city was throwing out into the country.’49 Picking up on the same red-brick vista, Mr Pooter’s house in Holloway was situated in the carefully named Brickfield Terrace.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, in the inner city, houses that had earlier been the homes of the Georgian well-to-do were colonized by the new professional classes, as both homes and offices. In earlier days, living outside the city, travelling on poorly lit roads, was dangerous and, even when not dangerous, difficult, as night travel had to be regulated by the times of the full moon. (As late as 1861 Trollope had one of his characters say, ‘it turns out that we cannot get back the same night because there is no moon’.)50 Now, with the progress of gas lighting across the country, that was one problem solved. Street-lighting was eulogized in the Westminster Review as early as 1829: ‘What has the new light of all the preachers done for the morality and order of London, compared to what had been effected by gas lighting!’51 With the increase in public transport it was no longer just the carriage owners who could live outside the bounds of the town and travel in to work daily. Gradually, the disadvantages of these old houses in inner London – they had no lavatories, or the lavatories had been installed long after the original building was planned and so were in inconvenient places; they were dark; the kitchens were almost unmodernizable – together with the increasing desire to separate home from work, meant that the professionals too moved to the ever expanding suburbs, and travelled in to work in what had previously been their homes. John Marshall, a surgeon living in Savile Row, just off Piccadilly in central London, in 1863 moved his family to suburban Kentish Town, on the edge of the city, after his fourth child was born: the better air and larger house made the daily trip back and forth to his consulting rooms in their old house worthwhile.52

Mrs Panton was certain that for ‘young people’ without too much money a house ‘some little way out of London’ was the ideal. ‘Rents are less; smuts and blacks* are conspicuous by their absence; a small garden, or even a tiny conservatory … is not an impossibility; and if [the man] has to pay for his season-ticket, that is nothing in comparison with his being able to sleep in fresh air, to have a game of tennis in summer, or a friendly evening of music, chess, or games in the winter, without expense.’54 This idyll was everything: greenery, fresh air away from city smoke, and, most importantly, a sense of privacy – a sense that once over your own doorstep you were in your own kingdom.

It was precisely this idyll, and the consequent rejection of city life, with its allurements but also its dangers – moral as well as physical – that was the impetus for the growth of suburbia. Walter Besant,† despite his interest in living conditions for the poor, remained an urbanized homme des lettres in his condemnation of this bourgeois development: ‘The men went into town every morning and returned every evening; they had dinner; they talked a little; they went to bed … the case of the women was worse; they lost all the London life – the shops, the animation of the streets, their old circle of friends; in its place they found all the exclusiveness and class feeling of London with none of the advantages of a country town …’ However, the noted urban historian Donald Olsen has argued that Besant had misunderstood the aims and desires of suburbanites: ‘The most successful suburb was the one that possessed the highest concentration of anti-urban qualities: solitude, dullness, uniformity, social homogeneity, barely adequate public transportation, the proximity of similar neighbourhoods – remoteness, both physical and psychological, from what is mistakenly regarded as the Real World.’55 W. W. Clarke, the author of Suburban Homes of London, published in 1881, praised districts precisely for their seclusion, their feeling of being cut off from the world.*57 The Builder, in 1856, suggested that all should live in the suburbs: ‘Railways and omnibuses are plentiful, and it is better, morally and physically, for the Londoner … when he has done his day’s work, to go to the country or the suburbs, where he escapes the noise and crowds and impure air of the town; and it is no small advantage to a man to have his family removed from the immediate neighbourhood of casinos, dancing saloons, and hells upon earth which I will not name.’58