Полная версия

The Secret Museum

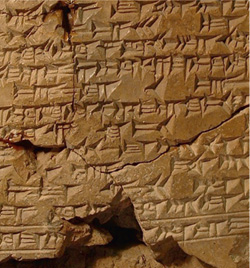

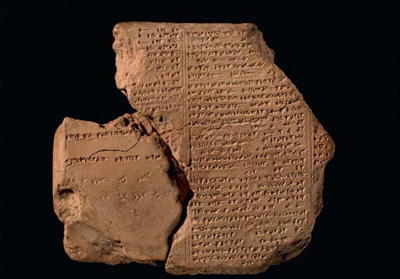

In the mid-nineteenth century, the world’s first archaeologists started digging around what was once Nineveh and found these pieces of baked, smashed-up clay with strange writing upon them. Some pieces that had been caught in the fire were black; others, which the fire had missed, were damp after millennia inside the earth. Fortunately some of these were still intact. All the archaeologists had to do was lay them out in the sun to dry, just as the scribes had done when they were creating the library back in the sixth century BC.

Thanks to the archaeological permit, the pieces were brought to England to the British Museum. Over time, the meaning of the writing was worked out. The Babylonians unwittingly left a code for the nineteenth century scholars who had discovered them.

The cuneiform tablets in the library are written either in Sumerian, which is unlike any language we have today, or in Akkadian, which is related to modern Semitic languages and easier to make sense of. The Babylonians also wrote bilinguals, with a line of Sumerian translated into a line of Akkadian. ‘The bilinguals are gold dust,’ said Finkel. ‘This was code-cracking with a crib from the codemaker.’ In the nineteenth century, the decipherers of Akkadian began with words like ‘mother’, ‘father’ and ‘tree’, and with numbers, then began to recognize prefixes and suffixes and slowly worked out the shape of the language. Once they’d worked out how to read Akkadian, they used the bilinguals to work out Sumerian.

Ever since then, curators have been gluing fragments of the clay tablets back together. ‘This is the greatest jigsaw of all time,’ Finkel explained. Each time a piece of clay is matched to another piece found smashed in the ground, a spell, an ancient recipe or a story comes back into the light.

Over the last three decades, Finkel has been slowly bringing more and more of ancient Nineveh into the twenty-first century. He loves the thrill of it: ‘There is nothing so satisfying as the moment when you rejoin two pieces of writing that have been separated for two and a half thousand years. Of course, the tablets are often broken at the most exciting moment, just when the hero finds the heroine, and says …’ Finding out the rest of the ancient story when you find the missing piece of clay tablet must be a sublime moment.

In many tablets that weren’t part of Ashurbanipal’s library, Finkel can recognize the work of different hands, just by looking at the shape of the calligraphy on different tablets; just as we all have different handwriting, each person who wrote on a clay tablet wrote in a slightly different way.

Almost all of the tablets, no matter what their size, are covered with writing, on the back and on the front. ‘If you write a postcard home to your auntie, you usually fill all the space up, don’t you?’, Finkel asked me. The scribes of Nineveh of 600 BC were no different.

They put a little more effort into their writing in one sense, though, by inventing right-justified text. If they couldn’t fill a line with text, they filled it with dots or drew a horizontal line. ‘It looks more authoritative. We do it sometimes, now that we have computers, but we don’t often make the effort, like they did, when we’re writing by hand.’ He pointed out the dots and lines on some clay tablets to me so I could see it for myself.

Finkel is a great host. He is able to make the Ancient Assyrian world come alive. When I left the Arched Room and walked into the public galleries of the British Museum, I found myself in Room 9, which is filled with reliefs from the king’s palace in Nineveh. Suddenly, everything in that room was shimmering with life. I now know that beyond the reliefs showing images of battle and war is a library filled with love letters, stories, poems, spells, recipes and a school exercise book of the last great king of Assyria.

Anyone can go to the Arched Room to take a look: ‘If you have the keys to treasure, as we do, it is unforgivable not to give people access to it. We’re very proud that anyone can come in here and read and see things they would like to see,’ Finkel explained. He often shows children the wonderful clay tablets and would love to persuade them to learn cuneiform and enjoy the rewards it brings. ‘There is still so much to do. We need students to study cuneiform and keep the giant jigsaw going.’

I had a look at his actual keys, the huge bunch of them he carries around each day. The biggest, oldest one is the key to the collection: it opens the Arched Room in which the tablets are stored. On it are the words ‘If lost, 20 shillings reward’ – not a generous reward then, considering the treasures the key can unlock for you.

[Irving Finkel in the Arched Room] Irving Finkel is assistant keeper for Ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures at the British Museum in London. He showed me a selection of clay tablets covered in cuneiform writing, the world’s oldest known script.

[A cut reed] Cuneiform appeared in ancient Iraq in about 3000 BC, first as a simple pictographic system, but rapidly evolving into a fluent means of recording language. The lines of the script (called wedges) were pressed into the clay with a cut reed, used like a pen; ‘It looked a bit like a chopstick,’ explained Finkel.

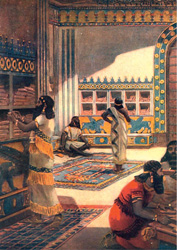

[The library at Nineveh] King Ashurbanipal built his capital in a city called Nineveh. At the heart of his palace he lovingly built up a library, filled with the clay tablets Finkel showed me in the British Museum.

[Cuneiform on a clay tablet] This clay tablet was King Ashurbanipal’s school exercise book. He may have put it in his library as a keepsake from the days when, as a child, he learned to write.

[The Epic of Gilgamesh] Until I met Finkel I didn’t know that the Epic of Gilgamesh came down to us written on a series of baked clay tablets.

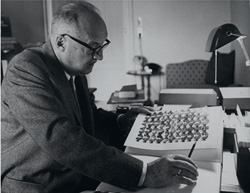

IN THE WORLD OF MUSEUMS, Vladimir Nabokov, who most famously wrote Lolita, which I loved, is better known for his butterfly expertise than he is for his novels. While writing piles of books, Nabokov collected butterflies across America, published detailed descriptions of hundreds of species and, in 1942, he was made curator of Lepidoptera at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. He set up shop in the museum, behind the scenes. I went to visit his former office.

The room is lined with metal drawers, each filled with rows of butterflies. Lots of his butterflies are stored in the drawers, along with thousands of others collected by different curators over the years. There is a desk pushed up against a window that looks out over the university campus. Nabokov worked from here. It’s a different desk that is now used by the current butterfly curator, but it is kept in the same place.

I stood by the desk and looked out of the window, and I saw students milling about chatting, eating lunch, reading and daydreaming. I imagined Nabokov doing the same, looking out, over butterflies, to watch the students at play. The only difference now is that today they’re reading iPads rather than books and there are food trucks, not packed lunches. Otherwise, I’d imagine Nabokov would feel right at home.

There is a photograph of him framed and hung on the wall beside the window. The image shows him holding up a butterfly, one of the hundreds he prepared in this room.

In the corner, by another window, is a small, dusty, wooden cabinet. It’s about a metre high, with two doors. Open the doors, and inside are hundreds of little glass vials, with corks for lids. Inside each one is a tiny butterfly penis. There are more butterfly bits on glass slides, stacked inside small boxes on shelves inside the cabinet.

There are also index cards that seem to be written in Nabokov’s writing; they describe each of the genitalia. Like the specimens, they are just as he left them in the 1940s.

I took out a box, picked out a slide and held it to the light. I could just about make out a little black spike: the genitalia of a single male blue butterfly. The glass vials used to have preserving liquid inside them but the fluid has dried out since Nabokov prepared them, so each butterfly penis now rattles around inside its bottle. It is really quite a strange thing to do – to hold a glass bottle, containing a butterfly’s penis, collected years ago by the famous author.

It might seem a bit of a weird thing for him to have done, that is, if you’ve read his novels but don’t know much about butterfly curating. But a butterfly curator wouldn’t find his collection strange at all. Studying male butterfly genitalia is one of the best ways of telling one species apart from another. It’s a better way than looking at just their wings and their size, because many butterflies look so similar.

The cabinet isn’t very important to the butterfly world – there is nothing of great scientific importance inside it – but I found it fascinating that Nabokov loved butterflies as much as books. His twin passions wove their way through his life from when he was young.

His father taught him as a child to chase, catch and collect butterflies while roaming around their family home of Vyra, in north-western Russia, and a love of butterflies was something they shared together. His mother showed him how to really look and to remember. These skills would come in handy for both writing and butterfly curating.

When his father was imprisoned in Russia for his political activities, eight-year-old Vladimir brought a butterfly to his cell as a present.

Nabokov was forced into exile in Europe in 1919. There he visited vast museum halls to look closely at the shimmering rainbow of butterflies on display. He married in Berlin in 1925, and he and his wife Vera roamed the mountains at weekends, collecting hundreds of specimens.

By 1940, he was living in Paris and, when the German tanks rolled in, he and his wife and their son, Dimitri, fled to America. In his apartment he left behind a set of European butterflies.

It was in America that he took up his first professional appointment in the world of butterflies, as a research fellow at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. He was appointed in 1942 and stayed for six years. He had imagined being a curator as a child and collected all the time.

In his autobiography, Speak, Memory, he describes how his governess sat on a tray full of butterflies he had collected himself and squashed them: ‘… A precious gynandromorph, left side male, right side female, whose abdomen could not be traced and whose wings had come off, was lost for ever: one might re-attach the wings, but one could not prove that all four belong to that headless thorax on its bent pin.’

At Harvard he saw plenty of these gynandromorphs, part of the huge collection created by butterfly curators over the decades. I saw one for myself; it is kept in one of the metal drawers – one wing was iridescent blue, the other half blue-half black with white flecks. Other interesting butterflies I saw, lifeless on pins, were a now-extinct Xerxces Blue, which once flew in the San Francisco area, and a huge green and yellow butterfly whose collector had been eaten by cannibals in Papua New Guinea.

Over 20 butterflies have been named in Nabokov’s honour, including ‘Lolita’ and ‘Humbert’, which are named after the two main characters in Lolita. He wrote the novel on index cards while on butterfly-collecting trips with Vera. After he’d finished writing, she’d type up his handwritten cards. When he tried to burn an early draft, she saved the pages from the flames.

The Nabokovs loved these long, butterfly-collecting adventures. They would set off from Harvard at weekends and during the holidays: Vera always at the wheel, because Nabokov never learned to drive. Once they drove a thousand miles across North America, taking on a blazing Kansas storm, just to spot a single species of butterfly.

Blue butterflies fascinated him, and he and Vera would pursue them all over the North American wilderness. Once he’d collected his specimens he would study their genitalia, looking carefully at the barbs and the shape of each one. His best work on butterflies was a paper about Polyommatus blue butterflies. He examined the genitalia of 120 of the creatures, which lived in the Neotropics, and found that different species had flown to the New World from Asia in a series of waves over millions of years. He said that ‘a modern taxonomist straddling a Wellsian time machine’ would have witnessed the colonization.

At the time, his findings weren’t really given much credit, but recently, in 2011, researchers at Harvard University sequenced DNA from the blues and found that Nabokov’s musings were correct. Blue butterflies flew in five waves from Asia to the New World – just as Nabokov had at one time emigrated with his family from Europe to America.

When asked in an interview for The Paris Review in 1967 whether he had felt at home during his time in America, Nabokov said he was ‘as American as April in Arizona’. Asked if anything reminded him of the Russia of his youth, he replied, ‘my butterfly hunting, in a loop of time, seemed at once to resume the butterfly chases of my vanished Vyra.’ The ‘fairly wild’ landscapes of north-western America were, he pointed out, ‘surprisingly similar to the Arctic expanses of northern Russia’.

Butterflies reminded him of home and, wherever life took him, he felt comfortable, butterfly net in hand, waiting to catch one of his precious, delicate creatures – rather like catching memories and ideas, and transforming them into characters at his writing desk. ‘My loathings are simple: stupidity, oppression, crime, cruelty, soft music,’ he once wrote. ‘My pleasures are the most intense known to man: writing and butterfly hunting.’

In a letter to his sister (1945), Nabokov wrote that ‘to know that no one before you has seen an organ you are examining, to trace relationships that have occurred to no one before, to immerse yourself in the wondrous crystalline world of the microscope, where silence reigns, circumscribed by its own horizon, a blindingly white arena — all this is so enticing that I cannot describe it.’

He became utterly hooked on collecting, pinching the delicate, colourful creatures at the thorax, then studying them carefully to find out everything he could about them. There was a price to pay – late in life, Nabokov’s eyesight failed, ruined by all the hours he’d spent looking at tiny genitalia under a microscope in the back room of Harvard’s museum.

[Nabokov at home, 1965] Vladimir Nabokov loved everything to do with butterflies; he read about them, drew them, wrote about them and collected them throughout his life.

[Nabokov’s butterfly cabinet] Nabokov kept his butterfly penis specimens inside little glass vials, packed into cigar boxes.

[Butterfly hunting] Nabokov and his wife Vera spent weekends butterfly hunting.

[Morpho butterfly] Rare genetic mutations produce gynandromorphs like this morpho butterfly, which is male on the left side and female on the right. Nabokov wrote about finding a gynandromorph as a young boy and was pleased that Harvard had one in its collection.

SO ASKED CHARLES DICKENS. He had at least three cats. One was named William, until Dickens realized she was a girl and renamed her Williamina. She had kittens, and he kept one, which became known as the Master’s Cat. It used to snuff out his candle to get his attention. A third cat was called Bob. He helped Dickens open his letters.

Bob wasn’t a spectacularly talented cat; the way he helped was rather odd. When dear Bob passed on in 1862, Georgina Hogarth, who was Dickens’s sister-in-law, had his little paw – which once padded around on the author’s lap, walking all over his writing or whatever he was trying to read, as cats seem to love to do – immortalized as the handle of a letter opener.

She had the strange feline and ivory piece engraved ‘C. D. In Memory of Bob. 1862’ and gave it to Dickens as a gift, to remind him of the love of his cat. He kept it in the library at Gad’s Hill, so that it was at his side as he wrote. It is now in the Berg reading room on the third floor of the New York Public Library in Manhattan. It shares a space with Dickens’s writing desk and chair – the ones he used when travelling – and 13 prompt copies the author had made to help him when doing public readings.

What’s a prompt copy? I’ll let Isaac Gewirtz, the Berg curator explain: ‘Dickens wasn’t only a great writer, he was a fantastic actor: he loved to perform his work, rather than simply read extracts from it. He filleted his novels, pulling out the most dramatic scenes. Then he had two or three copies printed and bound in case he lost one. His main copy he annotated, with stage directions and cues for himself. We have 13 annotated prompt copies here in the Berg.’

How brilliant to be able to see what Dickens’s audiences couldn’t.

One of the most popular of his readings was A Christmas Carol. The library owns the prompt copy he used to perform the story at public readings. He made this particular copy in a unique way.

Over to Isaac: ‘He had a binder remove the leaves from an 1849 copy of his novel and stick them to blank leaves which were then bound together as a new volume. Then he took this new book and read through his text, rewriting and simplifying tricky sentences. He got rid of evocative passages that set the scene in London and cut out descriptions of characters’ emotional states because he could convey those in the tone of his voice.’

He covered the copy with annotations, like a stage manager might annotate a script for a performance. He added cues, such as ‘Tone down to Pathos’ and ‘Up to cheerfulness’, which would remind him of how to play scenes; and he also underlined bits, such as ‘For it is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty Founder was a child himself.’ He used postage stamps as Post-it notes, to mark the places he wanted to read from. The corners of the stamps that were stuck on to the page are still there, while the bits that stuck out have fallen off.

His cat Bob, who was immortalized in the letter opener, was named after Bob Cratchit, Scrooge’s assistant in A Christmas Carol. It’s fitting then that Bob’s paw shares a cabinet with the library’s prompt copy of the tale the writer used for years at his wildly popular readings.

Several of these readings took place in America. He made two tours there: the first, in 1842, turned a bit ugly when he criticized American publishers for pirating his works, and when he travelled in the South, saw slavery at first hand for the first time and wrote angry articles against it. When he came back in 1867, all was forgiven. This time, he performed twice in New York, in the cavernous Steinway piano display hall on East 14th Street, and at the largest church in Brooklyn. People lined up in the snow for tickets – some even slept outside to be sure of a spot in the crowd: the queue, by opening time, was a mile long. The lucky people inside heard Dickens read from the book that is now in the library.

Reading it doesn’t give you the perfect idea of what his audiences heard each night – no two performances were the same. Sometimes Dickens would make things up on the spur of the moment, or slam the book shut with a flourish and perform from memory. He knew his stories by heart and could act them perfectly.

So how did the letter opener and prompt copies end up in New York? Well, when Dickens died, he bequeathed his estate to his sister-in-law, the lady who had given him the macabre letter opener. She wrote letters of authenticity for everything.

She sold some things, and passed others on to Dickens’s son. The letter opener and other Dickensian treasures were bought by a publisher in New York called E. P. Dutton; they had a sale, and two brothers – physicians of Jewish Hungarian descent called Albert and Henry Berg – turned up and bought the lot, to add to their glittering collection of American and British literature.

In 1940, the surviving brother, Albert, gave everything to the New York Public Library, and built an Austrian oak-panelled room for researchers. The Berg reading room was the result.

The street that leads to the New York Public Library is lined with quotations. I read them on my way to visit the library, then I walked up the steps to the entrance, which are guarded by two lions, cats a lot bigger than Bob.

When you walk into the Berg reading room, you see, on the right-hand side, a portrait of Henry Berg, beside the works of his favourite writer, Thackeray; and on the left-hand side is Albert’s portrait and all the writings of Albert’s favourite author, Charles Dickens. Only the researchers, most of whom come by appointment to read items in the collection, see the prompt copies, while waiting for a book to be brought for them from the vaults.

Albert Berg left a handsome sum to pay for future curators, and to make sure their collection of the works of 104 authors continued to grow. The first curator, John Gordon, who would become a friend of Albert Berg, acquired Virginia Woolf’s papers in 1958. He took them home with him and laid them out on the living room floor so that he and his family could have a good read through them all.

Isaac is in charge today, and he would never do such a thing. ‘That was a different time,’ he said. ‘Today we have works, printed and manuscript, by over 400 authors, with manuscripts and letters by and to Trollope, Keats, Wordsworth, Conrad, Hardy and Yeats, and the largest collection of Virginia Woolf and Auden papers in the world.’ They even have Virginia Woolf’s walking stick, which was found in the river after she had drowned herself.

The Berg Collection is still growing: ‘We have the papers of Annie Proulx, Paul Auster and my favourite author, Vladimir Nabokov.’ I told Isaac I’d seen Nabokov’s butterfly cabinet at Harvard University, and he said, ‘Oh yes, we have most of the journals he annotated and his scientific drawings of butterflies.’

I was interested to know what happens with modern authors, because surely so many first drafts are now on computer hard drives, and so many letters are sent by email. ‘Paul Auster tends to type letters and fax them, and keep the faxed copy, so the library has his outgoing and incoming letters, which is unusual. For several authors we have some floppy disks containing emails, and sometimes we get printouts of emails as well’.