Полная версия

The Secret Museum

A third freezer is being filled at the moment, and this is just the beginning: there is space for many more as the seed bank increases its collection. ‘You could get 38 double decker buses in this underground vault,’ says Stuppy. Already these freezers contain the greatest concentration of plant biodiversity on the planet: 10 per cent of the world’s wild plant species. In years to come, this will diversify even more. The MSB is hoping to save 25 per cent by 2020. We went back upstairs for a look at the incubator rooms, where seeds from Freezer A are periodically grown into seedlings to make sure that the seeds being stored are still healthy. Each brightly lit incubator is kept at a different temperature: 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25°C (41, 50, 59, 68, 77°F), depending on the type of plant they are set up to incubate. We popped our heads inside one; it smelt damp and mouldy. Inside were the seeds of a plant called Cousinia platylepis, and they were germinating well.

I asked Stuppy what happens to the germinating seeds. ‘They belong to the country of origin, so they are all destroyed. The only reason for growing them is to make sure the seeds in the freezer are still alive and healthy,’ he answered. He explained that bio-piracy is a big problem, which countries want to guard against, so acquiring seeds from other countries involves lots of contracts and teams of lawyers, and part of the deal is that no germinating plants will be grown without permission having been given by the country that sent the seed.

Brazil won’t let anyone keep seeds from its country, because it doesn’t want anyone to own seeds from Brazil which might be valuable later – a wonder drug perhaps, as yet to be discovered, that grows in the Amazon. ‘What about other countries?’ I asked. ‘America doesn’t have a large national seed bank for wild species (they have many large crop seed banks, though). Svalbard, Norway, only has crops. The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species at the Kunming Institute of Botany, in China, and the MSB are the two biggest seed banks for wild species in the world’, Stuppy explained.

In an ideal world, the MSB would not need to exist; instead, the plants contained in the frozen ark of seeds would be growing naturally in the wild. As it is, the MSB sees its project as a race against time. Who knows how many life-saving plants are growing on the Earth that are yet to be discovered? Imagine if one dies out before its unique properties are found? I wonder how many precious medicines are frozen in the vaults now.

We’re facing a global emergency. By the end of this century, half the world’s existing plants could be extinct. It is up to us to change. Our lives depend on plants for food, fuel, medicine, textiles, chemicals and for the oxygen we breathe. Without plants, we cannot survive, so why are we not doing more to grow what we can and to protect what we have? At least the seed bank is giving us options for the future while we sort things out. It’s a start.

Scientists at Kew are looking into the effects of climate change on plants, and are studying wild species that have traits that will be needed in crops if the Earth heats up – for example, short stems and bigger leaves; wild flowers are a miracle of adaptive design. Mainly, however, the frozen seeds are here as a life insurance for plant species and for human beings of the future.

When I left the seeds behind, I went for a wander around the gardens that surround the seed bank – the grounds of Wakehurst Place. The gorgeous landscape is a showcase for some of the frozen seeds beneath the ground, a future generation of beautiful flowering plants.

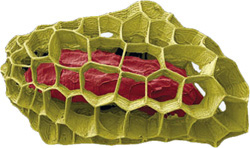

[A Mexican seed] Lamourouxia viscosa is one of millions of seeds inside the seed bank. Its honeycomb design is a perfect adaptation for catching puffs of wind.

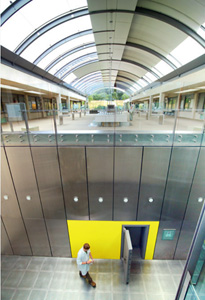

[Entrance to the seed bank] The grey door that leads into the seed bank is surrounded by a yellow panel, set into a wall of silver. You can see it from the floor above if you visit the public area of the seed bank.

[Freezer] We couldn’t go inside the freezers where the seeds are kept as it’s too cold – the staff who work there wrap up warmly in thick fleeces or big jackets.

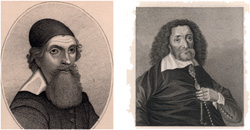

THE FIRST MUSEUM IN BRITAIN was The Ark, in Lambeth, London. Two gardeners, John and John Tradescant, opened it. They were father and son. The duo went on plant-hunting expeditions around the world to harvest the best of the new lands being discovered, and on their travels collected things they found interesting.

They were consumed by beauty, and gathered up bundles of flowers to fill English gardens: poppies and stocks from France; white jasmine from Catalonia; daffodils from Mount Carmel; tulip trees and a mimic passion flower from North America; as well as vegetables such as cos lettuce, plums, scarlet runner beans and possibly the first pineapple in England. In 1630, John Tradescant senior became Keeper of His Majesty’s Gardens, Vines and Silkworms. When he died, his son took over the role.

The Tradescants’ other great contribution to cultural life in England was their museum. They had amassed so many treasures while seeking out colourful plants that they decided, in 1626, to open up their home, Turret House, to the public. They called it The Ark and began charging people 6d to see the things that they had found in the New World and Europe. These treasures were things few people in England had ever seen before, and The Ark was described as a place ‘where a Man might in one daye behold and collecte into one place more curiosities than hee should see if hee spent all his life in Travell’. The collection included plants, a chameleon, a pelican, cheese, an ape’s head, shells, the hand of a mermaid, stones, coins, a toad-fish, birds from India – even a dodo, which at the time was not yet extinct.

My favourite thing in The Ark is Powhatan’s mantle, a coat belonging to the chief of the Native American Indian tribe that lived in Virginia when the first settlers arrived. Powhatan’s daughter was Pocahontas, and she married the leader of the English settlers, John Smith. Perhaps Tradescant senior collected it when he went there in 1637, almost certainly at the king’s request. He made three trips to Virginia and brought back all kinds of flowers, plants, shells and treasures including Tradescantia virginiania, a plant that still grows in England today.

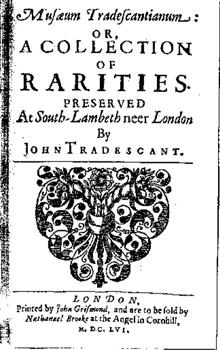

The Tradescants had a catalogue printed, Musaeum Tradescantianum, which was the first of its kind in Britain. It listed the objects in their collection, divided into sections like ‘shell-Creatures, Insects, Mineralls, Outlandish-Fruit’, ‘Utensills, House-holdstuffe’ and ‘rare curiosities of Art’. Everything was given equal weight, even things that were made up, like mermaids and unicorns.

Powhatan’s coat was catalogued in the ‘Garments, Vestures, Habits and Ornaments’ chapter, and described as ‘Pohatan, King of Virginia’s habit, all embroidered with shells, or Roanoke’. There were other things from Virginia too – a habit of bearskin and a match-coat made of raccoon skins. Just below these in the list were ‘Henry the 8, his stirrups, hawkes hods and gloves’ and, further down, ‘Edward the Confessor’s knit gloves’.

Both the Tradescants were buried in the churchyard at St Mary at Lambeth. Today the church is the Museum of Garden History, the first museum in the world dedicated to gardening. If you visit the collection you will see the tomb in the knot garden outside the museum. It is decorated with objects from the Tradescants’ collection. Legend has it that if you dance around it 12 times as Big Ben strikes, a ghost will appear. On the tomb is a poem probably written by John Aubrey describing the Tradescants, who:

… Liv’d till they had travelled Orb and Nature through, As by their choice Collections may appear, Of what is rare in land, in sea, in air, Whilst they (as Homer’s Iliad in a nut) A world of wonders in one closet shut…

Their ‘world of wonders’ passed eventually, and controversially, into the hands of Elias Ashmole, who gave it to the University of Oxford. The Tradescant Ark was opened as the Ashmolean Museum, in Broad Street, Oxford, in 1683. It was the first purpose-built public museum in the world.

There were three floors in the museum. The Ark collection was on display on the top floor, along with other natural history artefacts. The ground floor was used for lectures and teaching, and the basement was a laboratory. All the original signs above the doorways on each floor are there, explaining what each room was used for.

Today, The Ark and the Ashmolean Museum have moved across the city of Oxford, and the original Ashmolean building has been taken over by the Museum of the History of Science. When they renovated the building in 1999, they lifted the floorboards on the first floor. Beneath them were all kinds of treasures from the original museum.

When the first discovery was made, the current museum curators joined the builders in digging up these secrets. They felt like ‘floorboard archaeologists’, sifting through dust rather than the earth. They pulled out all kinds of simple things, most of them dating from the eighteenth century, rather than from the very beginning of the museum in 1683.

The ephemera they pulled out of the dust includes: the label from the key that belonged to Dr Plot, keeper of the museum; a letter from J. Chapman, who worked there; labels from portraits; a lizard; a book cover; the remains of a posy of flowers; and an unopened letter -which they aren’t going to open. I’m not sure how they can resist. I liked a small house, cut out of paper, made by someone daydreaming while at the museum, and a sketch of ‘Edward’, a keeper of the museum, with a little flower drawn beneath him.

There are things which whoever dropped them must have been upset to lose – a ring; a penknife and a child’s tooth with a hole drilled through it which had probably been tied on to a string as a keepsake. Perhaps the child’s father or mother wore it and crawled around on the floor of the museum looking for it when it fell off the string.

The most everyday things are the eighteenth-century pencil sharpenings and cherry stalks – very mundane at the time, but fascinating now. There are also lots of wax seals and coins. All of these tiny treasures that fell out of people’s pockets or off the walls, or slipped off tables, have survived by chance. They weren’t supposed to have made it into the twenty-first century, but that they did gives us a lovely feel for life in Britain’s first museum. Everything suggests a human touch. These things aren’t on display, because they’re fragile and utterly unique. They’re the only physical memories of the first museum in Britain.

Now, there are around 2,500 museums in Britain, and more than 55,000 museums in the world, each with unique collections; and most of the items in these collections are kept behind the scenes. More than 100 million people visit museums in Britain each year. I wonder what the Tradescants would have made of that? When they opened The Ark in their home in Lambeth, I bet they couldn’t have imagined the trend they were starting.

[John Tradescant the elder (c.15705–1638) and John Tradescant the younger (1608–62)] The two Tradescants, father and son, were gardeners with a shared passion for interesting plants and strange curiosities.

[Turret House, Lambeth, London] The Tradescants filled their home with so many curious treasures that they decided to charge the public to come and have a look. They called the first public museum in Britain ‘The Ark’.

[Powhatan’s mantle] A visitor to the Tradescant museum in 1638 recorded seeing ‘the robe of the King of Virginia’ and it was later catalogued as ‘Pohatan, King of Virginia’s habit, all embroidered with shells, or Roanoke’. The robe is now on display in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

[Musaeum Tradescantianum] John Tradescant junior wrote a catalogue of the collection – the first of its kind in Britain.

[Found beneath the floorboards] Museum curators felt like ‘floorboard archaeologists’ as they found pieces of history that had fallen beneath the floorboards of the original Ashmolean Museum.

I TOOK A TAXI TO the Museu de Arte Sacra to see the collection. When the taxi driver dropped me off, he said, ‘The museum is down the hill – walk down that little street. When you come out, come straight back up to this main road. Don’t hang around outside the museum, it can be dangerous.’ So, nervously, I legged it down a side street into the pretty courtyard of the museum.

Once safely inside, I met Francisco Portugal, who has been the curator of the museum for 14 years. He wanted to show me the most precious treasure they have in the collection: a glittering bejewelled cross, which lay hidden under the floor of the building for centuries as buried treasure. It hasn’t been exhibited for 40 years, as the museum is worried, now the area around the museum can be sketchy, that it might get stolen.

It is kept wrapped in a white cloth under lock and key inside a safe somewhere in the building. I didn’t see where. The curator asked his assistant to fetch it and bring it into his office for me to see. We waited there, looking out at the beautiful views of the ocean until his assistant reappeared. We stood up, and she unwrapped the treasure. It was a golden cross, decorated with precious jewels. As she placed it on the table, the sunlight streaming across the ocean and in through the curator’s office window bounced off the jewels and scattered around the room.

We gathered around to admire the cross. It’s a processional one, so would have been carried from the base. It was made in Brazil, out of precious gold and jewels. At the top is a circle of golden rays bursting out of another central circle, which looks like a smoothed crystal. The circle opens up to be a cubbyhole for Communion bread. On top of the golden rays sits a small golden cross. The piece is decorated with diamond droplets, amethysts, topaz, emeralds and rubies. Six cherubs float around its edges. You’ll just have to imagine it because there are no published photographs of this most sacred cross.

Once upon a time, the room we stood in was a monk’s bedroom. The whole museum has been shaped out of the former Convent of Saint Teresa de Avila, which was founded by the Order of Barefoot Carmelites in the mid-seventeenth century in the former capital of the colony. The monks who lived here were Portuguese. They arrived in Bahia in 1660 and built a little hospice by the sea; then, in 1685, they built a convent beside it, with a church modelled on the Church of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios (Our Lady of the Remedies), of Évora in Portugal, which dates from 1614.

The curator didn’t know exactly when the cross was made but, once it was in the monastery, the monks protected, polished and proceeded to the altar carrying it. During Communion, they would open the central crystal to take out the Communion bread with which to feed the souls of their fellow monks.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Bahia fought for independence from Portugal. The convent was taken over by Portuguese troops trying to keep Bahia for their country. The monks were forced out of the monastery, but before they fled they buried this precious cross beneath the floorboards of their home. After the monks, and then the troops, had left the convent, it fell into ruin and was left derelict for many years.

In 1958, the University of Bahia restored the convent and church and turned it into the Museum of Sacred Art, exhibiting art belonging to the church, and 500 treasures belonging to Brazilian and Portuguese museums, churches, convents and brotherhoods in Brazil. During the restoration, the cross was found in the ground. The restorers were overcome with pleasure at finding the buried treasure and carefully cleaned and polished it until it shone like new. They put it on display in the museum. However, within ten years, the area around the monastery went downhill and became rough and dangerous, so the cross was taken out of the public galleries and hidden away for safekeeping. There is still plenty to see in the museum itself: 1,500 pieces of sacred art from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are displayed in the rariefied atmosphere of the monks’ quarters, with a view of the glittering sea. You can see the first fresco painted in Brazil: a lotus flower with a female figure emerging from it.

The curator also took me into the former monks’ church so I could see how light the space was, with pews of dark wood and a silver altar upon which the cross may once have stood during a service, dazzling the monks as they prayed. I thought about the monks who worshipped here carrying the bejewelled cross, opening it up during Communion and lovingly polishing it after a service. They could never have imagined where it would end up: inside a safe, locked out of sight, just in case.

As I left the museum and crossed the courtyard that leads out into the street, I remembered why the cross was tucked away and decided to follow the taxi driver’s advice. I flew up the hill to the main road and hailed a cab, made it safely into the car and was thankful to have seen the beautiful cross safe in its charming museum.

[The Museum of Sacred Art, Salvador de Bahia] The museum is inside what was once the Convent of Saint Teresa de Avila, founded by the Order of Barefoot Carmelites in the mid-seventeenth century. It’s in a beautiful location by the sea, and must have once been a peaceful place to live.

BLYTHE HOUSE IS A LISTED building, on Blythe Road, in Kensington. It began life in 1903 as the headquarters of the Post Office Savings Bank. The post office building was the first in London to have electricity and was split in half, with men and women working on different sides, each with their own entrance. Today, the Science Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum use it as a store and archive. The Science Museum keeps its small objects here (its large objects are kept in a series of aircraft hangars, in an ex-RAF airbase in Wiltshire).

The Science Museum’s treasure trove in Blythe House includes over 100,000 objects collected in the early nineteenth century by a pharmaceutical entrepreneur with a Midas touch, the devoted collector Sir Henry Wellcome (1853–1936).

Wellcome owned a pharmaceutical company. He made a fortune thanks to his invention of medicine in tablet form. He called them tabloids – as in a mixture of tablets and alkaloids in a small packet; this is where we get the word we use to describe small newspapers. He used his wealth to set up the Wellcome Trust, which today is one of the biggest medical charities in the world. He loved to collect medical curios and books, and had agents dotted around the globe buying up things they thought would interest him. They collected so much stuff he didn’t get around to unpacking it all before he died. All of his books are stored in the Wellcome Library, on Euston Road, London. His objects were divided up between different museums around the world; some were put on display at the Wellcome Collection, on Euston Road, London (where the library is) and a tenth of his objects was brought over to Blythe House.

A team of archivists cataloguing the collection I came to see has been working for five years and has sorted over 230,000 items. It’s likely to take them another seven years to go through the lot. No one curator has ever seen it all. I spent three hours walking in and out of rooms, pulling open drawers and looking through shelves of artefacts with Selina Hurley, assistant curator of medicine at the Science Museum.

The medical treasures are sorted into rooms by theme. Each room has its own smell: the oriental room smells like incense; and the dentistry room like the bright liquid you gargle when you sit up, at the dentist’s. All of the rooms made me feel quite uneasy as they are filled with objects created to help people who were unwell.

We opened a door that led into a room filled with Roman votive offerings – models of injured parts of the body that were offered to a god to give thanks, or to ask for a cure; all over the walls are little clay feet, arms, legs, ears and even penises. Another room contains folk charms. Selina told me, ‘Every time I come in here I stumble across something different.’ Opening a drawer, she discovers a wizened object; ‘I think that’s a dried mole. Ah, here is a frog – he doesn’t smell too bad – he was used to cure cramp and kept in a little bag. A lot of things like this work through transference. You hold something and transfer your pain into it.’ Beside it is another example of this: a dog’s tooth used as a teething charm for babies (the pain would be transferred from the baby’s tooth to the dog’s). Lots of objects are labelled ‘curious object, use unknown’.

Another room is filled with piles of forceps to assist in birth; another with large glass storage bottles from pharmacies (one was for leeches). There was a cupboard with intricate Japanese memento moris (reminders that we all will die and to seize life with both hands), and a little ivory skeleton leaning on an alarm clock. I looked at a shelf lined with tiny ivory seventeenth-century anatomical figures. They were all lying flat, and I lifted their tummies off to reveal their insides. Particularly unsettling was a shelf crammed with prosthetic limbs, including a hand with a Bible on the end, and another with a scrubbing-brush attachment.

We came across the archives of Joseph Lister, the pioneer of antiseptic, and artefacts that belonged to Louis Pasteur, the French chemist and father of germ theory. There were items used by Pasteur in his study of anthrax, and some of his earliest preparations for quinine, dating back to 1820. Pretty much anything you could think of related to the history of medicine is in one of the rooms inside the Wellcome labyrinth. If you can’t find it, maybe it is still waiting to be unpacked.

Of all the objects I saw, I liked a rattle made of cane and puffin beaks the most. It is unlike anything else in the collection, and stood out, even from its nest inside a drawer. It seemed to be filled with life and spirit. At first I had no idea what it was, so I asked Selina, and she told me it was a rattle made by the Haida people, and would have belonged to a shaman.