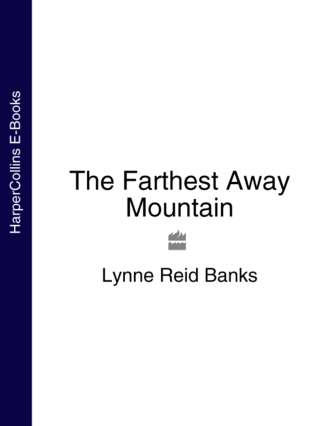

Полная версия

The Farthest Away Mountain

She stood under the last tree, staring above her at the cap.

“But how could it have got up there?” she thought. “I can’t possibly reach it!” It was as if one of the high branches had reached down and snatched the cap off her head as she passed. She thought of climbing up to get it, but the tree was smooth all the way up.

“I’ll just have to leave it,” she thought. “Oh dear!”

But nothing seemed so bad now she was out in the sunny meadow and away from the gloom of the wood. The birds sang as she ran through the deep grasses to the cabin, with the heads of the long-stemmed buttercups bouncing off her skirts. The place seemed deserted. She peered in at one of the windows, but the glass seemed to be covered with dust inside so that she couldn’t see. She went round to find the door. She turned one corner, and another, and another, and – but here was the same window again! There was no door.

“But how do people get in and out?” she wondered aloud.

“They don’t,” said a voice that sounded like an old rusty pump. “That’s the idea.”

Dakin jumped. The voice had seemed to come from inside the house.

“Where are you?” she said, looking through the window again.

The dust on the inside of the pane was disturbed, and now Dakin could see something – it looked like a little hand – rubbing a tiny clear place. Then the hand disappeared, and there was a minute eye, looking out at her.

There was a pause while the eye looked her up and down. Then the voice said, “You look all right. You can come in, if you want to.”

Dakin wasn’t at all sure she did, but it seemed rude not to, so she said, “How can I, as there’s no door?”

“Down the chimney, of course,” said the voice impatiently.

Dakin looked round. Leaning against the side of the cabin was a ladder, which she hadn’t noticed before, and up this she climbed rather reluctantly. She thought how dirty the chimney was at home and wished she’d gone straight past the cabin without stopping.

“Come on, come on!” the voice called irritably.

On the roof, Dakin scrambled to the chimneystack and looked down. It was a very big opening, and it didn’t look sooty, so she sat on the edge of it with her legs dangling in.

“Don’t be afraid, you won’t hurt yourself!” called the voice.

Dakin was getting very curious to see what the owner of the voice looked like, so she pushed herself off the rim of the chimney.

It was rather like going down a slide: there was a quick whoosh and the next thing she knew was that she was standing in a big, open fireplace which obviously hadn’t had a fire in it for years, if ever. She looked round. The inside of the cabin was just one room, very small and bare; it had plants growing in pots here and there, and that was about all in the way of furniture, but the most curious thing was a pool, sunk into the floor, with lily-pads floating on it; and up above it a big silvery green witchball dangled like a moon.

Dakin looked for the owner of the voice, but couldn’t see anyone.

“Hello,” croaked the rusty voice. “Here I am.”

Dakin stared. Sitting on one of the lily-pads on the pond was the biggest, oldest, wartiest frog she had ever seen. It came to her in a flash who it must be.

“You’re Old Croak!” she cried. “You’re not dead, after all!”

“Certainly I’m not dead!” answered the frog indignantly. “Why should I be dead? Dead, indeed! I’m in the prime of life.”

“I’m sorry,” said Dakin humbly. “Somebody told me you might help me, if only you weren’t dead. So I’m very glad to meet you.”

“Can’t help you,” said the frog at once. “Can’t possibly help you. But I’m glad to meet you, too. Sit down, sit down. Have a fly.”

There didn’t seem anywhere to sit except on the floor, so Dakin sat there. Then she saw that Old Croak was holding out a large fly which he apparently expected her to take.

“What – what am I to do with that?” she asked.

“Eat it, of course,” croaked her host. “What else? Delicious! One of my last,” he added sadly. “And who knows when there’ll be any more? But never mind, I don’t entertain often. Nothing but the best is good enough for the only visitor I’ve had in two hundred years.”

Dakin naturally supposed he was exaggerating about the time. As to the fly, she didn’t know what to say. She couldn’t take the poor old thing’s last one, especially when she didn’t want it.

“Thank you very much,” she said, “but as a matter of fact, I ate before I came. So why don’t you have it?”

“Really?” asked the frog, his wrinkled old eyes lighting up. “Well, in that case—” He popped the fly into his wide mouth and gulped it down, beaming with pleasure.

“I suppose there aren’t many flies inside here,” said Dakin.

“Hardly any,” said Old Croak, shaking his head. “Windows sealed up, no door… They don’t come down the chimney much. I suppose I shall starve to death one of these days. No doubt that’s what she wants. No one will care.” He heaved a deep, wheezy sigh, and sat brooding on the lily-leaf with his chin in his green hands.

“Who is ‘she’?” Dakin ventured to ask.

The frog started and nearly fell into the water.

“Shhh!” he hissed warningly. He looked all round, and then beckoned her closer. She kneeled on the edge of the pool, and he hopped from one leaf to another until he was able to speak right into her ear.

“The witch!” he muttered.

Dakin grew cold. “A real witch?”

“Oh, she’s real enough – by night, anyway, he added strangely.

“Have you ever seen her?” asked Dakin doubtfully. Of course there were plenty of stories about witches, but she wasn’t prepared to believe unless there was some proof.

“Seen her? Seen her?” hissed Croak, his eyes popping. “I see her every night, every night, mark you! Down that chimney she comes, in her dark glasses and all her coloured rags – for she’s not one of your black witches, you know, colour’s the thing with her – and she reaches up to the ceiling and takes down her witchball. Look! Do you see it hanging up there?”

Dakin looked at it again. Now she knew that it was a real witch’s ball, not just a silver decoration, she realized how sinister it was with its strange greenish sheen.

“Lights up at night, you know,” continued Croak in a hushed whisper. “That’s how she searches, every night, hunting… through the woods, all over the mountain. Then at dawn she comes back. Hangs the ball up. Throws me a few curses (though I usually hide in the pool where it’s safe). Takes herself off—”

“What is it she’s looking for?”

“Ah! I could tell you—” He stopped and looked round again. “I daren’t though. Not with that thing hanging there. Not with her being the way she is during the day. I’ve heard she sleeps in a cave up there near the peak, but I don’t believe it. I don’t believe she ever sleeps! I—” He stopped again, and a look of terror came into his eyes. “Listen!” he whispered. “Can’t you hear?”

Dakin listened. Everything had gone very quiet – the same kind of quiet as in the wood. Outside the murky window the sun had gone in and the cabin had grown suddenly so dark that Dakin could hardly see Old Croak at all. She swallowed fearfully and put out her hand. The frog gripped one finger with his little cold pads.

“Can’t you hear?” he whispered again.

And now, Dakin did hear. A terrible roaring groaning gnashing sound, faint at first, and then growing louder and louder, as if some dreadful creature were approaching, grumbling and talking to itself.

“What is it?” whispered Dakin in the darkness.

The frog had to swallow several times before he answered. “Drackamag,” he gulped at last.

“But who – what – is Drackamag?” asked Dakin, as the terrifying noise got closer and closer.

CHAPTER FOUR Drackamag

“Shhh!”

Now it was almost as dark as night, and the grumbling and roaring was right outside the window, sounding as thunder would sound if it were right next to your ear. It stopped for a moment, and then a deep, rumbling voice shouted down the chimney:

“Croak! Who have you got in there?”

“Don’t speak!” muttered Old Croak hoarsely. “He’s very stupid. If we don’t speak, he may go away.”

“I heard that!” roared Drackamag, and the vibrations made the lily-pads rock like cockleshells on a rough sea. “Stupid, am I? We’ll see who’s stupid one of these days when I put my foot right down on this little house of yours, wait and see if I don’t!”

Croak cowered down as if expecting the cabin to be crushed over his head at any moment.

“Come on, you ugly little lump of nothing! Who’s in there? I heard someone laugh. Horrible! Frightened me out of me wits. No one’s laughed on this side of the wood since – well, not for two hundred years, eh, Croak? We can’t be having that sort of thing, it might lead to anything! Birds singing, bees humming – dangerous, dangerous, Croak! Eh? Eh?”

“You shouldn’t have laughed,” whispered the frog to Dakin in a shocked tone.

“Why not?” asked Dakin, feeling suddenly braver. If the simple sound of a laugh could frighten the terrible Drackamag, he couldn’t be such a monster after all, however big he was.

“I heard a girl’s voice!” exclaimed the thunderous voice outside. “She sounded happy! If you’ve got anybody good in there, Croak, I’m warning you – Madam won’t like it! Now, send her out this minute, or I’ll go and wake the old girl up and ask her if I can crunch your house down!”

Dakin stood up. Her legs shook a bit, but not too badly, considering.

“Don’t go out!” hissed her friend frantically. “Let him do what he likes!”

“I’m not going out,” Dakin assured him loudly. “I’m just going to laugh.”

“No! NO! Not that!” howled the voice outside, and now the lily-pads danced so wildly that Old Croak fell into the water with a splash.

But Dakin was already laughing, and didn’t notice. It wasn’t any too easy to laugh, as there was nothing very funny about the situation; but it was important, so Dakin did it. She remembered the time Margle, her brother, had scoffed at the calf who fell into the mud-hole and immediately afterwards fallen in himself. She thought of the expression on the face of the hen when the chick she’d raised turned out to be a duck, and had hopped into the pond. She recalled the hornet-fly that wanted to sit on the Pastor’s nose last Sunday in the sermon. New laughter bubbled up in her with each thing she thought of, and soon the mere idea of the dreadful Drackamag being frightened was enough to keep her going.

Her laughter rang out, peal after joyful peal, until the crest of the mountain seemed to echo it back to her. But at last she was so tired, and her tummy ached so much, that she couldn’t laugh any more, and she sat down on the floor, too exhausted by her effort to make another sound.

She looked round. The first thing she noticed was that it was light again: the sun was shining in through the dusty window. Dakin realized that the sun hadn’t really gone in, but that Drackamag’s body had shut it out, like a black cloud. Birds outside were singing and all the sounds of a sweet summer noon-time were pouring down the chimney like music. Drackamag and his fearful roaring voice were, for the moment, gone.

She looked for Old Croak, and finally found him huddled behind a plant with his eyes tight shut and his pads in his ears. She tried to make him hear her, but of course he couldn’t, so at last she gently touched him.

He leapt clean into the air with fright, landed on the ground and did a beautiful swallow-dive into the pond where he vanished, leaving only a bubble to show where he’d gone.

Dakin was alone again.

CHAPTER FIVE The Spikes

Well, it was time to be on her way. But there was one more thing she could do. Opening her knapsack, she took out the toffee, and laid it in the fireplace at the foot of the chimney. Almost at once, a fly who happened to be passing overhead saw it and buzzed down to investigate. Then came another, and another. Old Croak would find a feast awaiting him when at last he had to surface for air.

Getting out of the chimney, Dakin discovered, was a different matter from getting in, and for a while it seemed she was doomed to stay there for ever. But in trying to draw herself up, she accidentally touched a rough place in the bricks and a little rope-ladder suddenly fell out of the inside rim of the chimney-pot and dangled before her. In no time at all she was sliding down the sloping roof, and clambering down the ladder into the sunny meadow again.

The meadow was wide, and as long as she was out in the sunshine she felt strangely safe. Could it be that whatever dark forces held the farthest-away mountain in their spell were as afraid of the light as they were of the happy sounds of laughter and birdsong? If so, then Dakin felt she might have discovered a very helpful secret in Old Croak’s cabin.

But no meadow stretches forever and, quite abruptly, the grass stopped and she found herself walking on rocks, not the smooth, well-worn kind in the green river at home, but spikey, sticking-up rocks, like sharp teeth or knives. Her feet slipped between them and she had to wrench them free. Sometimes a piece of rock she hadn’t noticed would trip her up. She knew if she fell she’d hurt herself badly, and it really did seem, after a while, as if the rocks were alive and doing their utmost to make her stumble and fall in amongst them.

Whenever she looked ahead the jagged teeth, like the spears of a vast army, seemed to stretch for miles, ahead and on both sides; and even looking back, she couldn’t see any sign of the meadow. The sun had really gone in now and the sky overhead was grey and threatening. She grew more and more weary, but there wasn’t one friendly flat surface to rest on, just the endless, treacherous sea of spikes. It was no good turning back, she could only go on. It was worse than the wood.

At last Dakin grew so tired she knew that very soon she must either sit down and rest, or fall down. Her head had begun to whirl and she realized she must be terribly hungry. Even without the little troll, her knapsack felt like lead, and her heart felt almost as heavy.

As she staggered on she felt a lump come into her throat. First she told herself it was just tiredness, then, as it grew bigger, that it was hunger, but despite all her efforts to deceive herself, two big tears bloomed slowly on her lower eyelashes and made two wet, crooked paths down her brown cheeks.

They met on the end of her chin, and fell with a small splash on a particularly spiteful-looking point of rock.

What happened next would have surprised Dakin if she hadn’t already had more surprises that day than she knew how to deal with. The rock on which her tear had fallen began to melt, like a fast-burning wax candle. First the sharp point disappeared, then the thickening column beneath it sank and sank with a faint hissing sound, until it had quite melted away and there was nothing left but a flat place – exactly the size and shape of Dakin’s foot.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.