Полная версия

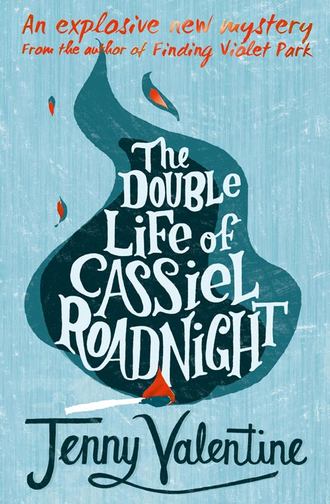

The Double Life of Cassiel Roadnight

It was the killing of the engine that woke me again, the lack of sound, and then the slam of Edie’s door. I opened my eyes, alone on a dirt track surrounded by nothing but green. It was getting dark. It was unreal, like waking from one dream into another. I’d never been in that much space before. The wind blew across the land and straight at me like now I was there it had something to aim for. I could hear it singing through and over and under the car. For less than a second I wondered if Edie had left me here, if she’d worked it out and abandoned me. And then I heard the creak of a gate and she was back, striding through the sheer emptiness, opening and closing the door, bringing a little piece of the gale and the smell of cold grass in with her.

“Welcome home, Cass,” she said.

The car stumbled through the open gate, slicing through wet mud and tractor marks. Edie got out to shut it again behind us. The green plain narrowed into a tree-lined path, and then there it was. Cassiel’s mother’s dream house. There was a light on downstairs and it spilled out warm and yellow into the air. Edie beeped the horn twice and the front door flung open. It wasn’t until the porch light snapped on that I saw her properly, thin and dark and windblown, an older version of Edie, just as fragile-looking, just as small. She put her hands to her mouth the same as Edie did when she first saw me. Then she was jumping and waving, her shouts vanishing into the wind. She ran at the car. I watched her close in on us like a tornado, like water. There was no escaping her.

Edie stared at me. “What’s wrong?” she said. “You look like you’re going to be sick.”

“Nothing.”

“You’re scared. What are you scared of?”

I didn’t have time to answer. Cassiel’s mother was on us, on me. She wrenched open the door with both hands. The wind grabbed my hair and filled my ears, and she tried to pull me straight out by my arms and throw herself on me at the same time.

I heard Edie get out of the car on the other side, free and unnoticed, like she was invisible, like she wasn’t there. I saw myself suddenly from the outside, in this wind-racked, mud-filled place, pretending to be this woman’s son. I couldn’t breathe.

Wouldn’t she know? Wouldn’t she know as soon as she touched me?

Cassiel’s mother had bangles that clanked and rang, and her nails were bitten so hard, so far down I couldn’t look at them. I tried to get out of the car with her still clinging to me. I tried to stand up.

“My boy,” she said, and then she pulled me into the crook of her neck, my forehead on her shoulder, my back bent over like a scythe. Her clothes smelled of the warm inside, of dog and log fires and cooking, of cigarette smoke. I felt her breathing, thin and weak, like she was worn out from years of doing the same. She laughed into my hair and tightened her thin arms across my back. Her breath smelled of flowers and ash.

I stored it in a quiet and empty place in my mind. So this was what a mum felt like.

Cassiel’s mother drew back to look at me. Her eyes were wild and triumphant, and at the dark centre of them there was something like fear. I tried not to let her see how scared I was. I listened to the countdown in my head that ended with her disappointed scream.

It didn’t come. I got to zero and she hadn’t let go.

“I never thought I’d see you again,” she said, shaking her head, the threat of tears drowning her voice. “I never thought I’d see you.”

She grabbed my shirt, my mended charity-shop shirt, like she thought her hand might go straight through it. “You’re real.” She whispered it.

“Yes.”

“You came back.”

“Yes.”

I don’t know how long we stood there for, in that wet, freezing air. She rocked, like she was holding a baby, but it was me holding her up, I think. Edie had gone in. A dog came out on to the porch, sniffed the air, stretched its back legs and went in again. My car door was still open and the light was on inside. I worried briefly about the battery. The trees thrashed wildly at the house, like they knew there was something to be angry about, like they knew what wrong was being committed there. I glared at them and they thrashed wildly at me too.

When the phone rang inside the house, Cassiel’s mother jumped, like she’d been sleeping, like she’d been miles away.

“That’ll be Frank,” she said, and she wiped her eyes and smoothed her hair back, like whoever Frank was he’d be able to see her. “Let’s go in,” she said. “Let’s talk to Frank.”

She took my hand to walk with me, but when I pulled back to get my bag and shut the car door, she didn’t wait. She let go and went ahead to the house, and left me there for a moment in the wind and the dark alone.

Inside the house was warm and smelled of cinnamon and onions and wood smoke. Underneath the wood smoke there was something cloying and rotten, like dustbins, like decay.

It was horribly bright. I felt the light fall on each line and hollow of my face that was different to Cassiel’s. I felt my face change, looming and hideous in its strangeness. I saw my reflection in the mirror. I was me, not him. Wasn’t it obvious?

Edie and her mother weren’t looking, not really. They can’t have been. But they might at any moment. I stood still and waited for that moment to come.

I looked around me at the kitchen, dark and low-ceilinged with a black slate floor and blood-red cupboards, an old range pumping out heat, a long, scrubbed table down the middle. There was a sofa against the wall, torn and scruffy, with old velvet cushions that for a sharp second made me think of Grandad.

The dog was in his basket in the corner. He didn’t get up. He lifted his eyes, wagged his tail at us lazily, thump-thump-thump on the floor. He was a wiry mongrel of a thing, old and coarse and greying. I scratched his neck, read the name Sergeant on his collar. He rolled over and exposed the bald pink of his tummy, the upside-down spread of his smile.

Cassiel’s mother was flushed from the cold air, her knuckles bone-white where she gripped the phone.

“Is that Frank?” I said.

Edie nodded. “He just got our messages.”

Cassiel’s mother held the phone out to me. “Cass,” she said. “Come and speak to Frank. Let your big brother hear your voice.”

I took the phone out of her hand and she stroked the side of my face. I looked her in the eye. I waited for her to notice.

“Hello, Frank,” I said, and I stood still and obedient while she stroked me.

Frank was smoking. I could hear the wet suck of him pulling on a cigarette, the thickened taking in of breath. He laughed, and in my mind I saw his mouth and all the smoke pouring from it.

“Cass,” he said. “You’re home.” His voice was low and warm.

“Yes,” I said.

He sounded calm and confident. I liked the sound of him. “I can’t wait to see you,” he said.

“Me too.”

“I’m coming straight home.”

“When. Tonight?”

“In the morning.”

“OK. Good. Thanks.”

Would it be him that saw it? Would he look at his brother and see the liar underneath?

“It’s a miracle, Cass,” Frank said, his mouth close to the phone, his lips brushing against the mouthpiece as he spoke so the sound of him grazed my ears.

“Not really,” I said.

“No, believe me,” Frank was saying. “You are a miracle.”

Cassiel’s mother was holding her hand out for the phone. “Mum wants you,” I said.

“No. Tell Helen I’ve got to go,” he said. “Tell her I’ll see her tomorrow.”

“OK.”

“And Cass,” he said.

“Yes?”

“Welcome home.”

He put the phone down. I listened for a moment to the empty line.

I had a big brother now too.

Helen. Cassiel’s mum’s name was Helen. Was that what Cassiel called her? Or did he call her Mum? She was standing so close to me. She could have counted my eyelashes from where she was standing. She didn’t seem to notice my scars, the old holes in my ears, the thousand other differences there must be. Didn’t she see me?

“He’s gone,” I said.

The focus of her eyes slipped a little, but she kept them on me. I watched them go. I watched them loosen and fade and come back, her pupils lost in clouded, muddied blue, her gaze slack. Cassiel’s mother was high. She didn’t see me at all.

Edie was watching me. I wondered if she saw the shock on my face. I wondered if I was supposed to know.

Helen sat down at the table, smiled at nothing, started rolling a cigarette.

Edie picked my bag up and opened the door on to a dark hallway. “Are you coming?” she asked me.

“Where?” Helen said.

“I was going to give him a tour. He doesn’t know where anything is.”

They spoke about Cassiel, even though I was standing right in front of them. I supposed that’s just what they were used to, Cassiel getting talked about, Cassiel not being there. I supposed it was fitting, in a way.

Edie looked at me. “Do you want to?”

“Yes,” I said. “Yes, I do.”

In the dark hallway she opened a door on to the stairs. She held my bag in her hand, low by the strap, and dropped it on the bottom step. The banisters were wood, painted a pale bluish grey. The steps were dusty, dancing with fluff and crumbs, dots of paper and scraps of tobacco.

“Did you like the kitchen?” she said.

“It’s nice,” I said. “Pretty.”

She smiled. Her teeth and the whites of her eyes were like stone in the dark. “Not words I’m used to hearing you say.”

Did I have to be that careful? Did the words pretty and nice betray me? I was trying to be a good boy. I was trying to be like him, that’s all.

“What’s in here?” I said, walking through a space on my right. It was a little room with boots and coats and a load of boxes.

“Not much,” Edie said, turning away, opening a door opposite. “This one’s the sitting room.”

There was a big low fireplace and a glass chandelier, three battered armchairs and a thick rug on the floor. It was cold.

“We hardly ever go in here,” Edie said. “It’s nicer in the kitchen.”

She took me upstairs. She pulled the door to the stairway shut behind us. Her voice echoed between the narrow walls. “Why did you look so surprised?” she said.

“When?”

“When you looked at Mum.”

I tried to think.

“Do you think she’s worse?” Edie said.

I shrugged. “Hard to say.”

“She gets them off the internet now,” Edie said.

“What?”

“Valium. Diazepam. God knows. The doctor wouldn’t give her enough any more. He was telling her to stop.”

“Maybe she should.”

Edie looked hard at me for a second. “You never thought that before,” she said.

Damn. “Didn’t I?”

She took the last bend in the stairs. “What did you call them? Mummy managers.”

I tried to smile. “Oh, yeah.”

“Keep her half tuned out, so she doesn’t care what you’re up to. Ring a bell?”

It was even colder up there and our feet were loud on the wooden floor.

“You and Frank both,” she said. “You’re as bad as each other.”

Cassiel’s room was the third door on the right, after Frank’s room and the bathroom. Across the hallway were Helen’s and Edie’s.

Edie went into Cassiel’s room before me, strolled right in like it was no big deal. Dust swarmed in the light from the ceiling. I thought about breathing it in. I thought about it swarming like that inside my nose and mouth and throat and lungs.

I stopped in the doorway like the air itself was pushing me away. It wasn’t my room. It wasn’t my stuff to touch.

“What?” Edie said.

I looked past her. “Nothing.”

“Is it different?” she said. “I tried to make it look exactly the same.”

I said, “I’m just looking.”

The dust swarmed harder and faster around me when I walked in, like it was angry. Here was his mother holding me tight, here was his sister asking me in. But even the dust in Cassiel’s room knew I wasn’t him.

“It’s tidier,” she said. “You can’t miss that.”

I looked at his stuff. I moved around the room, picking things up, touching them, opening drawers. A mirror with an apple printed on it, a skin drum, a picture of two banjo players in a small metal frame. A book about mask-making, a folder of drawings, a skateboard. A stack of postcards, a laptop, a poster for a film I’d never heard of. Clothes, washed and ironed and folded and waiting for someone to wear them for two whole years. They were way too small for me. They’d never fit him now.

I thought about Cassiel watching me from somewhere, from a daydream, from a park bench, from a checkout, from Heaven or Hell or the plain cold grave, wherever he might be.

I wondered how much he would hate me for what I was doing.

I wondered when he was coming to get me back.

“Does it feel weird?” she said.

“A bit,” I said.

“Yeah,” she said. “I’ve got this running commentary in my head. My little brother’s home.”

She sounded like an announcer at a railway station. “My little brother is home and in his room.”

No, he’s not, the commentary in my head said. No, he isn’t.

“Do you like it?” she said. “Do you like your room?”

I didn’t answer. She didn’t notice.

“It’s bigger than the old one, isn’t it? Do you like the colour? It’s called Lamp Room Grey or something. Mum said it was boring. I think it’s cool.”

I smiled.

“You hate it,” she said.

“I don’t.”

Helen came upstairs and knocked on the open door. Edie took her eyes off me for a moment to look at her.

“You are so tall,” Helen said.

“Am I?”

“I forgot you’d be two years older.” She leaned on the doorframe. She crossed her arms around herself and she watched me.

“I said the same thing,” Edie said. “It’s like you grew in five minutes.”

Helen nodded. “It’s a lot to take in.”

When she blinked, she blinked slowly, like her eyes would have been happy staying closed.

“Where have you been, Cassiel?”

“What happened? Tell us what happened.”

They spoke at the same time, almost. They were nothing but questions. I couldn’t answer them. My disguise was paper-thin. I didn’t know who Cassiel Roadnight was or what he’d say. If I spoke I’d eat away at it, I’d just show myself lurking underneath, the rotten core.

“Not now,” I said.

“When?” Edie said.

“Leave it, love,” said Helen.

It was quiet, tense, like a stand-off. I could hear us all breathing. I thought about how big Cassiel’s breaths were, how many times a minute his heart beat.

“Are you hungry?” Helen said.

I should be. I don’t think I’d eaten since Edie called. But I wasn’t. My stomach was like a closed fist. There was too much to think about. Too much could go wrong.

Cassiel would be. He would be relaxed and hungry and tired. Cassiel was home.

“I think so,” I said.

“Good. Let’s eat.”

They left the room ahead of me and I listened to them go along the landing and down the stairs. I stopped in the doorway and looked back into his room. The dust was still frenzied in the light from the bulb. I switched it off.

It disappeared, just like that.

EIGHT

I never ate meat in my life before I was Cassiel Roadnight. Not once.

According to Grandad, being a vegetarian wasn’t just about health or cruelty or money or flavour, it was also about manners. He said that stealing milk and eggs and honey was enough of a liberty without hacking off someone’s leg and then drowning it in gravy. He had a point.

He taught me how to cook. He trusted me with all the sharp knives and all the boiling water I could get my hands on. We ate rice and beans and vegetables. We ate a lot of curry. We ate like kings.

That’s what Grandad used to say.

After the accident, when I wasn’t allowed to see Grandad any more, they tried to make me eat meat. They put withered, puckered, stinking things on my plate and told me if I didn’t eat them there’d be trouble. They said they were good for me.

They didn’t know the first thing about what was good for me.

I told them that. I screamed it in their faces. I said I didn’t eat meat. I said I wanted my Grandad. I threw the food at them. I threw it at the walls and the windows and their faces. I threw it anywhere it wanted to land. I didn’t eat their meat. I didn’t do it.

I’d rather have starved.

Cassiel’s favourite food was meatballs. Helen put a plateful down in front of me and it was clear from the look on her face that meatballs were something I was supposed to get all excited and nostalgic about.

“Meatballs,” I said. “Thanks.”

Edie said, “How many times have we talked about this, Mum? Cass sitting here having supper, just like this.”

Helen shook her head. “I don’t know,” she said. “Hundreds.”

I cut a piece off a meatball, dripping in sauce. I tried to make my face right. I tried to smile and not grimace, tried to close my eyes in delight not panic, tried to swallow not gag. They watched me like hawks.

“Delicious,” I said, still chewing. They tasted like salt and shit and gristle.

“As good as you remember?”

“Better.”

I got through two. I drank a lot of water. I broke them down into fractions of themselves, sixteen more to go, fourteen more, eight, one. In my head I said sorry to Grandad, and to the lamb or the pig or the mixture of creatures I was eating. I put my knife and fork together with four of them still swimming on my plate.

“What’s wrong?” said Helen.

“That’s not like you,” said Edie.

I said, “I haven’t eaten like this in a while. My stomach isn’t quite up to it.”

I allowed Cassiel, wherever he was, to chalk up a point against me. I told myself it didn’t matter. I reminded myself I didn’t have a choice.

So I wasn’t a vegetarian any more. I wasn’t me any more either.

When you’re running, when you’re moving from place to place, day after day, it’s hard to watch yourself eat. You steal. You pick through the bins and try not to realise it’s you. You try not to think about what you’re doing. You learn where the shops dump their rubbish, what night’s the best night. You rely on what other people waste.

Finish your food? No, don’t, because somebody watching from outside might want it.

After meatballs there was ice cream. I let it melt in my mouth and it slipped, rich and over-sweet, down my throat. I did it without thinking.

“Why d’you always eat it like that?” Edie said. “It’s gross.”

Funny to have such a thing in common with Cassiel – the way we ate ice cream.

“Have you been in London? Or Bristol? Or Manchester? Or where?” Edie said.

“He’s tired,” Helen said, putting her cool hand on my forehead.

“Have you been living rough?” Edie said. “On the streets?”

What would the answer to that be? It was pretty likely. If you run away from home when you’re fourteen, you don’t usually end up in the penthouse suite.

“Now and then,” I said.

Helen shook her head. “And being on the streets was better than being here?” She looked at Edie and then at me. “I don’t understand.”

“Nor do I,” Edie said, “When you put it like that.”

My stomach was giddy with rich and strange food. I listened to their spoon scrapes, their soft slurps and swallows.

“Why did you go off?” Edie said.

I looked at her food, only at her food. I said, “I didn’t know what else to do.”

“I don’t believe you,” Edie said.

I kept my voice soft. I kept it level. “You don’t have to.”

“What was so awful?” Helen said. “What was so bad that you had to go?”

I didn’t say anything.

Edie said, “You shouldn’t have punished us all like that.”

“Frank said you were in trouble,” Helen said. “He was worried about you.”

“I don’t understand why you didn’t call,” Edie said. “I’ll never understand why you let us all think you were dead.”

Was it OK to say sorry? Would Cassiel say sorry for that? I wanted to say it.

Edie couldn’t stop. “You didn’t think about what it would do to us,” she said. “It didn’t cross your mind.”

“You don’t know that,” Helen said.

“Yes I do, Mum. I know him better than you. I’m right, aren’t I, Cassiel?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“I am,” she said. “And you do know. And I will never forgive you.”

“You said on the missing persons thing that you’d never give up,” I told her. “You didn’t say you’d never forgive.”

I worried instantly that I shouldn’t have spoken. In the silence that followed I thought I’d done something wrong.

“You didn’t make it easy,” Edie said.

Helen started to clear the plates. I got up to help her.

“Sit down,” I said, my hand on her shoulder. “I’ll do this.”

“Nice try,” Edie said. “Walk out for a couple of years and then tiptoe back in, all soft and sweet and helpful, like that’s going to fool anybody.”

I stacked the bowls as quietly as I could.

“Who the hell are you pretending to be, Cassiel Roadnight?” she said.

“Leave him,” Helen said. “That’s enough.”

“I’m sorry, Edie,” I said. “I’m sorry, Mum.”

Edie growled.

Helen looked at me and I smiled. “Your eyes have changed colour,” she said. She was surprised to hear herself say it.

I didn’t move. Edie pushed the ice cream away from her and leaned towards me. “They haven’t,” Edie said.

“They have,” said Helen. “They’re different. How’s that possible?”

Because I’m not him. Because I’m a grotesque copy. Because I’m a cuckoo in the nest.

“It’s not possible,” said Edie. “That’s the point.”

“Look at me,” Helen said.

I didn’t want to. I didn’t want her to see me. “I am.”

“Your eyes used to be blue,” she said.

“They are blue.”

“They’ve changed,” Helen said. “They’re not the same blue. They’re darker.”

I waited for them both to notice. I waited for the horror to dawn on their faces. I knew his mother would see.

“Yeah, right,” Edie said under her breath. “And you can count how many fingers I’m holding up.”

“What?” Helen said.

“You’re not remembering them right,” Edie said. “That’s all it is.”

“I am,” Helen said. “I know my son’s eyes.”

Tears welled up suddenly in hers. I hated to see his mother so ruined and so upset and so completely right. It hurt. And it was my fault.

“Do you think I don’t know my own son?” she said, to neither of us.

I put my arms around her. I said, “It’s OK, Mum,” even though it wasn’t, even though if she knew the truth she would scream the house down if I tried to touch her.

“I’ve got to go to bed,” she said. “I’m suddenly so tired.”

Edie said, “Tranquillisers will do that.”

“Don’t, Edie,” I said, without thinking.

It stunned her. It stopped her dead. I knew what the look on her face meant. I knew what she was thinking. Cassiel wouldn’t have said that.

Helen took my hand and looked at it like she’d never seen it before. She kept hold of it until I moved away, until she had to let go.

She kissed me on the cheek, delicate and cool.

“Night, Cassiel, Night, Edie,” she said when she was halfway up the stairs. “Sleep well.”

I tried to look everywhere but at Edie. I washed up and wiped the table and made a big deal of finding out where everything went and putting it away.

She watched me the whole time. I could feel her watching. I watched myself through her. I became aware of every little movement, every little sound, like the next thing I did would give me away.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.