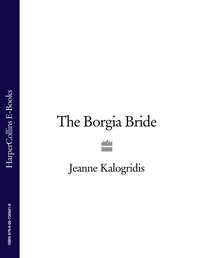

Полная версия

The Borgia Bride

‘If he does,’ Alfonso whispered, ‘I will come to you, and we can play quietly. If you’re hungry, I can bring you food.’

I smiled and laid a palm on his cheek. ‘The point is, you mustn’t worry. There’s nothing Father can do that will really hurt me.’

How very wrong I was.

Donna Esmeralda was waiting outside the Great Hall to lead us back to the nursery. Alfonso and I were in a jolly mood, especially as we moved past the classroom where, had this not been a holiday, we would have been studying Latin under the uninspired tutelage of Fra Giuseppe Maria. Fra Giuseppe was a sad-faced Dominican monk from the nearby monastery of San Domenico Maggiore, famed as the site where a crucifix had spoken to Thomas Aquinas two centuries earlier. Fra Giuseppe was so exceedingly corpulent that both Alfonso and I had christened him in Latin Fra Cena, Father Supper. As we passed by the classroom, I solemnly began the declension of our current favourite verb. ‘Ceno,’ I said. I dine.

Alfonso finished, sotto voce. ‘Cenare,’ he said. ‘Cenavi. Cenatus.’

Donna Esmeralda rolled her eyes, but said nothing.

I giggled at the joke on Fra Giuseppe, but at the same time, I recalled a phrase he had used in our last lesson to teach us the dative case. Deo et homnibus peccavit.

He has sinned against God and men.

I thought of Robert’s marble eyes, staring at me. I wanted to know they were listening.

Once we were in the nursery, the chambermaid joined Esmeralda in carefully removing our dress clothes while we wriggled impatiently. We were then dressed in less restrictive clothing—a loose, drab gown for me, a plain tunic and breeches for Alfonso.

The door to the nursery opened, and we turned to see our mother, Madonna Trusia, accompanied by her lady-in-waiting, Donna Elena, a Spanish noblewoman. The latter had brought her son, our favourite playmate: Arturo, a bony, long-limbed hellion who excelled at chases and tree-climbing, both sports I enjoyed. My mother had changed from her formal black into a pale yellow gown; looking at her smiling face, I thought of the Neapolitan sun.

‘Little ones,’ she announced. ‘I have a surprise. We are going on a picnic.’

Alfonso and I whooped our approval. We each grasped one of Madonna Trusia’s soft hands. She led us from the nursery into the castle corridors, Donna Elena and Arturo in tow.

But before we reached freedom, we had an unfortunate encounter.

We passed my father. Beneath his blue-black moustache, his lips were grim with purpose, his brow furrowed. I surmised he was headed for the nursery to inflict my punishment. Given the current circumstances, I could also guess what it would be.

We came to an abrupt stop.

‘Your Highness,’ my mother said sweetly, and bowed. Donna Elena followed suit.

He acknowledged Trusia with a curt question. ‘Where are you going?’

‘I am taking the children on a picnic.’

The Duke’s gaze flickered over our little assembly, then settled on me. I squared my shoulders and lifted my chin, defiant, resolved to show no sign of disappointment at his next utterance.

‘Not her.’

‘But Your Highness, it is a holiday…’

‘Not her. She misbehaved abominably today. It must be dealt with at once.’ He paused and gave my mother a look that made her wilt like a blossom in scorching heat. ‘Now go.’

Madonna Trusia and Elena bowed again to the Duke; my mother and Alfonso both shot me sorrowful little glances before moving on.

‘Come,’ my father said.

We walked in silence to the nursery. Once we arrived, Donna Esmeralda was summoned to witness my father’s formal address.

‘I should not be required to waste an instant of my attention on a useless girl child with no hope of ascending to the throne—much less such a child who is a bastard.’

He had not finished, but his cursory dismissal so stung that I could not let an opportunity to retaliate pass. ‘What difference does it make? The King is a bastard,’ I interrupted swiftly, ‘which makes you the son of a bastard.’

He slapped my cheek so hard it brought tears to my eyes, but I refused to let them spill. Donna Esmeralda started slightly when he struck me, but managed to keep herself in check.

‘You are incorrigible,’ he said. ‘But I cannot permit you to further waste my time. You are not worth even a moment of my attention. Discipline should be the province of nursemaids, not princes. I have denied you food, I have closeted you in your room—yet none of this has done anything to calm you. And you are almost old enough to be married. How shall I turn you into a proper young woman?’

He fell silent and thought a long moment. After a time, I saw his eyes narrow, then gleam with understanding. A slight, cold smile played on his lips. ‘I have denied you the wrong things, haven’t I? You’re a hard-headed child. You can do without food or the outdoors for a while, because while you like those things, they are not what you love most.’ He nodded, becoming ever more pleased with his plan. ‘That is what I must do, then. You will not change until you are denied the one thing that you love above all else.’

I felt the first pangs of real fear.

‘Two weeks,’ he said, then turned and addressed Donna Esmeralda. ‘She is to have no contact with her brother for the next two weeks. They are not permitted to eat, to play, to speak with each other—not even permitted to catch a glimpse of each other. Your future rests on this. Do you understand?’

‘I understand, Your Highness,’ Donna Esmeralda replied tautly, her eyes narrowed and her gaze averted. I began to wail.

‘You cannot take Alfonso from me!’

‘It is done.’ In my father’s hard, heartless expression, I detected traces of pleasure. Filius Patri similis est. The Son is like the Father.

I flailed about for reasons; the tears that had gathered on the rims of my eyes were now in true danger of cascading onto my cheeks. ‘But…but Alfonso loves me! It will hurt him if he can’t see me, and he’s been a good son, a perfect son. It’s not fair—you’ll be punishing Alfonso for something he didn’t do!’

‘How does it feel, Sancha?’ my father taunted softly. ‘How does it feel to know you are responsible for hurting the one you love the most?’

I looked on the one who had sired me—one who so cruelly relished hurting a child. Had I been a man, and not a young girl, had I borne a blade, anger would have overtaken me and I would have slit his throat where he stood. In that instant, I knew what it was like to feel infinite, irrevocable hatred for one I helplessly loved. I wanted to hurt him as he had me, and take pleasure in it.

When he left, I at last wept; but even as I spilt angry tears, I swore I would never again permit any man, least of all the Duke of Calabria, to make me cry.

I spent the next two weeks in torment. I saw only the servants. Though I was allowed outside to play if I wished, I refused, just as I petulantly refused most of my meals. I slept poorly and dreamed of Ferrante’s spectral gallery.

My mood was so dark, my behaviour so difficult that Donna Esmeralda, who had never lifted a finger against me, slapped me twice in exasperation. I kept ruminating over my sudden impulse to kill my father; it had terrified me. I became convinced that without Alfonso’s gentle influence, I should become a cruel, half-crazed tyrant like the father and grandfather I so resembled.

When the two weeks finally passed, I seized my little brother and embraced him with a ferocity that left us both breathless.

When at last I could speak, I said, ‘Alfonso, we must take a solemn oath never to be apart again. Even when we are married, we must stay in Naples, near each other, for without you, I will go mad.’

‘I swear,’ Alfonso said. ‘But Sancha, your mind is perfectly sound. With or without me, you need never fear madness.’

My lower lip trembled as I answered him. ‘I am too much like Father—cold and cruel. Even Grandfather said it—I am hard, like him.’

For the first time, I saw real anger flare in my brother’s eyes. ‘You are anything but cruel; you are kind and good. And the King is wrong. You aren’t hard, just…stubborn.’

‘I want to be like you,’ I said. ‘You are the only person who makes me happy.’

From that time on, I never once gave our father cause to punish me.

II

Slightly more than three years passed. The year 1492 arrived, and with it a new pope: Rodrigo Borgia, who took the name Alexander VI. Ferrante was eager to establish good relations with him, especially since previous pontiffs had looked unkindly on the House of Aragon.

Alfonso and I grew too old to share the nursery and moved into separate chambers, but we were apart only when sleep and the divergence in our education required it. I studied poetry and dance while Alfonso perfected his swordsmanship; we never discussed our foremost concern—that I was now fifteen, of marriageable age, and would soon move to a different household. I comforted myself with the thought that Alfonso would become fast friends with my future husband and would visit daily.

At last, a morning dawned when I was summoned to the King’s throne room. Donna Esmeralda, could not entirely hide her excitement. She dressed me in a modest black gown of elegant cut and fine silk, with a satin brocade stomacher laced so tightly I gasped for air.

Flanked by her, Madonna Trusia, and Donna Elena, I crossed the palace courtyard. The sun was obscured by heavy fog; it dripped onto us like soft, slow rain, spotting my gown, covering my face and carefully arranged hair with mist.

At last we arrived at Ferrante’s wing. When the doors opened onto the throne room, I saw my grandfather sitting regally on his crimson cushions; beside him stood a stranger—an acceptable-looking man of stocky, muscular build. Next to him was my father.

Time had not bettered Alfonso, Duke of Calabria. If anything, my father was more temperamental—indeed, vicious. Recently, he had called for a whip and flogged a cook for serving his soup cold; he beat the poor woman until she fainted from loss of blood. Only Ferrante was able to stay his hand. He had also dismissed, with much cursing and shouting, an aged servant from the household for failing to properly shine his boots. To quote my grandfather, ‘Wherever my eldest son goes, the sun retreats behind the clouds in fear.’

His face, while still handsome, was a portrait in misery; his lips twitched with barely-repressed indiscriminate anger, his eyes emanated an unhappiness he delighted in sharing. He could no longer bear the sound of childish laughter; Alfonso and I were required to maintain silence in his presence. One day I forgot myself, and let loose a giggle. He reached down and struck me with such force, I stumbled and almost fell. It was not the blow that hurt as much as the realization that he had never lifted a hand against any of his other children—only me.

Once, when Trusia had believed me to be preoccupied, she had confided to Esmeralda that she had gone one night to my father’s chambers only to find it in total darkness. When she had fumbled about for a taper, my father’s voice emerged from the blackness: ‘Leave it so.’ When my mother moved towards the door, he commanded: ‘Sit!’ And so she was compelled to sit before him, on the floor. When she began to speak, in her soft, gentle voice, he shouted: ‘Hold your tongue!’

He wanted only silence and darkness, and the knowledge that she was there.

I bowed gracefully before the King, knowing my every action was being sized up by the common-looking, brown-haired stranger beside the throne. I was a woman now, and had learned to funnel all my childish stubbornness and mischief into a sense of pride. Others might have called it arrogance—but ever since the day my father had wounded me, I had vowed never to let myself show hurt or any sign of weakness. I was perpetually poised, unshakable, strong.

‘Princess Sancha of Aragon,’ Ferrante said formally. ‘This is Count Onorato Caetani, a nobleman of good character. He has asked for your hand, and your father and I have granted it.’

I lowered my face modestly and caught a second glimpse of the Count from beneath my lowered eyelashes. An ordinary man of some thirty summers, and only a count—and I a princess. I had been preparing myself to leave Alfonso for a husband—but not one so undistinguished as this. I was too distraught for a gracious, appropriate reply to spring quickly to my lips. Fortunately, Onorato spoke first.

‘You have lied to me, Your Majesty,’ he said, in a deep, clear voice.

Ferrante turned in surprise at once; my father looked as though he might strangle the Count. The King’s courtiers suppressed a gasp at his audacity, until he spoke again.

‘You said your granddaughter was lovely. But such a word does no justice to the exquisite creature who stands before us. I had thought I was fortunate enough to gain the hand of a princess of the realm; I had not realized I was gaining Naples’ most precious work of art as well.’ He pressed his palm against his chest, then held out his hand as he looked into my eyes. ‘Your Highness,’ he said. ‘My heart is yours. I beg you, accept such a humble gift, though it be unworthy of you.’

Perhaps, I mused, this Caetani fellow will not make such a bad husband after all.

Onorato, I learned, was quite wealthy, and continued to be outspoken concerning my beauty. His manner towards Alfonso was warm and jovial, and I had no doubt he would welcome my brother into our home whenever I wished. As our courtship proceeded rapidly, he surprised me with gifts. One morning as we stood on the balcony looking out at the calm glassy bay, he moved as if to embrace me—and instead slipped a necklace over my head.

I drew back, eager to examine this new trinket—and discovered, hung on a satin cord, a polished ruby half the size of my fist.

‘For the fire in your soul,’ he said, and kissed me. Whatever resistance remained in my heart melted at that moment. I had seen enough wealth, taken its constant presence for granted long enough, to be unimpressed by it. It was not the jewel, but the gesture.

I enjoyed my first embrace. Onorato’s trimmed golden-brown beard pleasantly caressed my cheek and smelled of rosemary-water and wine, and I responded to the passion with which he pressed his strong body against mine.

He knew how to pleasure a woman. We were betrothed, so it was expected that we would yield to nature when alone. After a month of courting, we did. He was skilled at finding his way beneath my overskirt, my dress, my chemise. He used his fingers first, then thumb, slipped between my legs, and rubbed a spot that left me quite surprised at my own reaction. This he did until I was brought to a spasm of most astounding delight; then he showed me how to favour him. I felt no embarrassment, no shame; indeed, I decided this was truly one of the greatest joys of life. My faith in the teaching of priests was weakened. How could anyone deem such a miracle a sin?

This behaviour occurred on several occasions until, at last, he mounted me, and inserted himself; prepared, I felt no pain, only enjoyment, and once he had emptied himself in me, he took care afterwards to bring me pleasure as well. I so delighted in the act, and so often demanded it, Onorato would laugh and call me insatiable.

I suppose I am not the only adolescent to mistake lust for love, but I was so taken by my future husband that, during the last days of summer, as a whim, I visited a woman known for seeing the future. A strega, the people called her, a witch, but though she garnered respect and a certain amount of fear, she was never accused of evil and on occasion did good.

Flanked by two horsemen for protection, I travelled from the Castel Nuovo in an open carriage with my favourite three ladies-in-waiting: Donna Esmeralda, who was a widow, Donna Maria, a married woman, and Donna Inez, a young virgin. Donna Maria and I joked about the act of love and laughed all the way, while Donna Esmeralda pursed her lips at such scandalous talk. We passed beneath the glinting white Triumphal Arch of the Castel Nuovo, with Falcon’s Peak, the Pizzofalcone, serving as its inland backdrop. The air was damp and cool and smelled of the sea; the unobstructed sun was warm. We made our way past the harbour along the coast of the Bay of Naples, so bright blue and reflective of the sky that the horizon between the two blurred. We headed toward Monte Vesuvio to the east. Behind us, to the west, the fortress of Castel dell’Ovo stood guard over the water.

Rather than ride through the city gates and attract attention from commoners, I directed the driver to take us through the armoury, with its great cannons, then alongside the old Angevin city walls that ran parallel to the shoreline.

I was besotted with love, so giddy with happiness that my native Naples seemed even more beautiful than ever, with sunlight gleaming off the white castles and smaller stucco homes built on the rises. Though the date had not been set for the nuptials, I was already dreaming of my wedding day, of myself presiding as mistress of my husband’s household, smiling at him across a laden table surrounded by guests, of the children that would come and call out for their Uncle Alfonso. This was all I required of the strega—that she confirm my wishes, that she tell me the names of my sons, that she give me and my ladies something fresh to laugh and gossip about. I was happy because Onorato seemed a kind, pleasant man. Away from Ferrante and my father, in the company of Onorato and my brother, I would never become like the men I so resembled, but rather like the men I loved.

In the midst of my girlish giggling my eye caught sight of Vesuvio, destroyer of civilizations. Massive, serene, grey-violet against the sky, it had always seemed benign and beautiful. But that day, the shadow it cast on us grew deeper the closer we moved towards it.

A greater chill rode upon the breeze. I fell silent; so in turn did each of my companions. We rumbled away from the city proper, past vineyards and olive orchards, into an area of softly rolling hills.

By the time we arrived at the strega’s house—a crumbling ruin of a house built against a cavern—sombreness had overtaken us. One of the guards dismounted and announced my arrival with a shout at the open front door, while the other assisted me and my attendants from the carriage. Chickens scattered; a donkey tethered to a porch beam brayed.

From within, a woman’s voice called. ‘Send her in.’ It was, to my surprise, strong, not frail and reedy, as I had imagined.

My ladies gasped. Indignant, the first guard drew his sword, and stepped upon the threshold of the house-cave.

‘Insolent crone! Come out and beg Her Highness Sancha of Aragon for forgiveness! You will receive her properly.’

I motioned for the guard to lower his sword, and moved beside him. Try as I might, I could see nothing but shadow inside the doorway.

The woman spoke again, unseen. ‘She must come in alone.’

Again my man instinctively raised his sword and took a step forward; I thrust an arm into the air at his chest level, holding him back. An odd dread overtook me, a pricking of the skin at the nape of my neck, but I ordered calmly, ‘Go back to the carriage and wait for me. I shall go in unaccompanied.’

His eyes narrowed in disapproval, but I was the future King’s daughter and he dared not contradict me. Behind me, my ladies murmured in dismay, but I ignored them and entered the strega’s cave.

It was unthinkable for a princess to go anywhere alone. I was at all times attended by my ladies or by guards, except for those rare moments when I saw Onorato alone—and he was a noble, known to my family. I ate attended by family and ladies, I slept attended by my ladies; when I was a young girl, I had shared a bed with Alfonso. I did not know what it meant to be alone.

Yet the strega’s presumptuous request did not offend me. Perhaps I understood instinctively that her news would not be good, and wished only my own ears to receive it.

I recall what I wore that day: a deep blue velvet tabard, since it was cool, and beneath, a stomacher and underskirt of pale grey-blue silk trimmed with silver ribbon, covered by a split overskirt of the same blue velvet as the tabard. I gathered the folds of my own garments as best I could, drew a breath, and entered the seer’s house.

A sense of oppression overtook me. I had never been inside a peasant’s house, certainly never as dismal a dwelling as this. The ceiling was low, the walls crumbling and stained with filth; the floor was dirt and smelled of chicken dung—facts that augured the ruination of my silk slippers and hems. The entire house consisted of one tiny room, lit only by the sun that streamed through the unshuttered windows. The furnishings consisted of a small, crude table, a stool, a jug, a hearth with a cauldron, and a heap of straw in one corner.

Yet there was no one inside.

‘Come,’ the strega said, in a voice as beautiful, as melodious as one of Odysseus’ sirens. It was then I saw her: standing in a far, shadowed corner of the hovel, in a narrow archway behind which lay darkness. She was clad entirely in black, her face hidden by a dark veil. She was tall for a woman, straight and slender, and she lifted a beckoning arm with peculiar grace.

I followed, too mesmerized to remark on the lack of proper courtesy toward a royal. I had expected a hunchbacked, toothless crone, not this woman who moved as though she herself were the highest-born nobility. Into the dark passageway I went, and when the strega and I emerged, we were in a cave with a vast, high ceiling. The air was dank, making me grateful for the warmth of my tabard; there was no hearth here, no place for a fire. On the wall was a solitary torch—a rag soaked in olive oil—which provided barely enough light for me to find my way. The witch stopped at the torch briefly to light a lamp, then we proceeded further, past a feather bed appointed in green velvet, a fine, stuffed chair, and a shrine with a large, painted statue of the Virgin on an altar adorned with wildflowers.

She motioned for me to sit at a table much more accommodating than the one in the outer room. It was covered with a large square of black silk. I sat upon a chair of sturdy wood—finely crafted by an artisan, not made for a commoner—and carefully spread my skirts. The strega set the oil lamp down beside us, then sat across from me. Her face was still veiled in black gauze, but I could make out her features after a fashion. She was a matron of some forty years, dark-haired and complected; age had not erased her beauty. She spoke, revealing the pretty curves made by the bow of her upper lip, the handsome fullness of the lower.

‘Sancha,’ she said. It was familiar in the most insulting way, addressing me without my title, speaking without being spoken to first, sitting without permission, without genuflecting. Yet I was flattered; she uttered my name as if it were a caress. She was not speaking to me, but rather releasing my name upon the ether, sensing the emanations it produced. She savoured it, tasted it, her face tilted upwards as if watching the sound dissolve in the air above.

Then she looked back down at me; under the veil, amber-brown eyes reflected the lamplight. ‘Your Highness,’ she addressed me at last. ‘You have come to know something of your future.’

‘Yes,’ I answered eagerly.

She gave a single, grave nod. From a compartment beneath the table, she produced a deck of cards. She set them on the black silk between us, pressed her palms against them, and prayed softly in a language I did not understand; in a practised gesture, she fanned them out.

‘Young Sancha. Choose your fate.’

I felt exhilaration mixed with fear. I peered down at the cards with trepidation, moved an uncertain hand over them—then touched one with my forefinger and recoiled as though scalded.