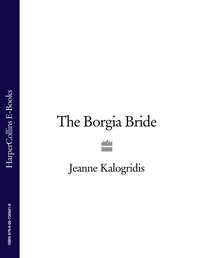

Полная версия

The Borgia Bride

‘I am going to find Ferrante’s dead men,’ I told him. I intended to enter the King’s private chambers without his permission, an unforgivable violation of protocol even for a family member. For a stranger, it would be a treasonous act.

Above his goblet, Alfonso’s eyes grew wide. ‘Sancha, don’t. If they catch you—there is no telling what Father will do.’

But I had been struggling with unbearable curiosity for days, and could no longer repress it. I had heard one of the servant girls tell Donna Esmeralda—my nursemaid and an avid collector of royal gossip, that it was true: the old man had a secret ‘chamber of the dead’, which he regularly visited. The servant had been ordered to dust the bodies and sweep the floor. Until then I had, along with the rest of the family, believed this to be a rumour fuelled by my grandfather’s enemies.

I was known for my daring. Unlike my younger brother, who wished only to please his elders, I had committed numerous childhood crimes. I had climbed trees to spy upon relatives engaged in the marriage act—once during the consummation of a noble marriage witnessed by the King and the Bishop, both of whom saw me staring through the window. I had smuggled toads inside my bodice and released them on the table during a royal banquet. And I had, in retaliation for previous punishment, stolen a jug of olive oil from the kitchen and emptied its contents across the threshold of my father’s bedchamber. It was not the olive oil that worried my parents so much as the fact that I had, at the age of ten, used my best jewellery to bribe the guard in attendance to leave.

Always I was scolded and confined to the nursery for lengths of time that varied with the misdeed’s audacity. I did not care. Alfonso was willing to remain a prisoner with me, to keep me comforted and entertained. This knowledge left me incorrigible. The portly Donna Esmeralda, though a servant, neither feared nor respected me. She was unimpressed by royalty. Though she was of common blood, both her father and mother had served in Alfonso the Magnanimous’ household, then in Ferrante’s. Before I was born, she had tended my father.

At the time, she was in the midst of her fourth decade, an imposing figure: large boned, stout, broad of hip and jaw. Her raven hair, heavily streaked with grey, was pulled back tautly beneath a dark veil; she wore the black dress of perpetual mourning, though her husband had died almost a quarter of a century before, a young soldier in Ferrante’s army. Afterwards, Donna Esmeralda had become devoutly religious; a gold crucifix rested upon her prominent bosom.

She had never had children. And while she had never taken to my father—indeed, she could scarcely hide her contempt for him—when Trusia gave birth to me, Esmeralda behaved as though I was her own daughter.

Although she loved me, and tried her best to protect me, my behaviour always prompted her reproach. She would narrow her eyes, lips tugged downward with disapproval, and shake her head. ‘Why can you not behave like your brother?’

That question never hurt; I loved my brother. In fact, I wished to be more like him and my mother, but I could not repress what I was. Then Esmeralda would make the statement that cut deeply.

‘As bad as your father was at that age…’

In the great dining hall, I looked back at my little brother and said, ‘Father will never know. Look at them…’ I gestured at the adults, laughing and dancing. ‘No one will notice I’m gone.’ I paused. ‘How can you stand it, Alfonso? Don’t you want to know if it is true?’

‘No,’ he answered soberly.

‘Why not?’

‘Because it might be.’

I did not understand until later what he meant. Instead, I gave him a look of frustration, then, with a whirl of my green silk skirts, turned and threaded my way through the throng.

Unseen, I slipped beneath the archway and its grand tapestry of gold and blue. I believed myself to be the only one to escape the party; I was wrong.

To my surprise, the huge panelled door to the King’s throne room stood barely ajar, as if someone had meant to close it but had not quite succeeded. I quietly pulled it open just enough to permit my entry, then shut it behind me.

The room was empty, since the guards were busy eyeing their charges out in the Great Hall. Though not quite as imposing as the Hall in size, the room inspired respect: against the central wall sat Ferrante’s throne: a structure of ornately carved dark wood cushioned in crimson velvet, set upon a short dais with two steps. Above it, a canopy bore Naples’ insignia of the lilies, and on either side, arched windows stretched from floor to ceiling, framing a glorious view of the bay. Sunlight streamed through the unshuttered windows, reflecting off the white marble floors and the whitewashed walls, giving a dazzling, airy effect.

It seemed too open, too bright a place to hold any secrets. I paused for a moment, examining my surroundings, my exhilaration and dread both growing. I was afraid—but, as always, my curiosity overpowered my fear.

I faced the door leading to my grandfather’s private apartments.

I had entered them only once before, a few years earlier when Ferrante was stricken by a dangerous fever. Convinced he was dying, his doctors summoned the family to make their farewells. I was not sure the King would even remember me—but he had laid his hand on my head and graced me with a smile.

I had been astonished. For my entire life, he had greeted me and my brother perfunctorily, then looked away, his gaze distant, troubled by more important matters. He was not given to socializing, but I caught him at odd moments watching his children and grandchildren with sharp eyes, judging, weighing, missing no detail. His manner was not unkind or rude, but distracted. When he spoke, even during the most social of family events, it was usually to my father, and then only of political affairs. His late marriage to Juana of Aragon, his third wife, had been a love match—he had no need to further his political advantage, to produce more heirs. But he’d long ago spent his lust; the King and Queen moved in separate circles and now spoke only when occasion demanded it.

When he had lain in his bed, supposedly dying, and put his hand upon my head and smiled, I had decided then that he was kind.

Back in the throne room, I drew a breath for courage, then moved swiftly toward Ferrante’s private chambers. I did not expect to find any dead men; my anxiety sprang from the consequences of my actions were I caught.

On the other side of the heavy throne room door, the sound of the revellers and music grew fainter; alone, I could hear the sweep of my silk skirts against marble.

Tentatively, I opened the door leading to the King’s outer chamber. I recognized the room, having passed this way when Ferrante had been sick. Here was an office, with four chairs, a large desk, tables, many sconces for late-night illumination, a map of Naples and the Papal States upon the wall. There was also a portrait of my great-grandfather Alfonso wearing the jewelled sword he had brought from Spain, which Ferrante had worn earlier in the Duomo.

Daringly, I pressed against walls, thinking of hidden compartments, of passageways; I scanned the marble floor for cracks that hinted at staircases leading down to dungeons, but found nothing.

I continued on through an archway into a second room furnished for the taking of private meals; here again, there was nothing of note.

All that remained was Ferrante’s bedchamber. This was sealed off by a heavy door. Squashing all thoughts of capture and punishment, I boldly opened it, and made my way into the most interior and private of the royal chambers.

Unlike the other bright, cheerful rooms, this one was oppressive and dark. The windows were covered with hangings of deep green velvet, blotting out the sun and the air. A large throw of the same green covered most of the bed, accompanied by numerous blankets of fur; apparently, Ferrante suffered from chills.

The chamber was fairly unadorned given the status of its resident. The only signs of grandeur were a golden bust of King Alfonso on the mantel, and gold candelabra flanking either side of the bed.

My gaze was drawn to an interior wall, where another door stood fully opened. Beyond it lay a small, windowless closet, outfitted with a wooden altar, candles, rosary, a statuette of San Gennaro, and a cushioned prayer bench.

Yet at the termination of that tiny chamber, past the humble altar, was another portal—this one closed. It led further inward, its edges limned with a faint, flickering light.

I experienced excitement mixed with dread. Had the maidservant told the truth, then? I had seen death before. The extended royal family had suffered loss, and I had been paraded past the pale, posed bodies of infants, children, and adults. But the thought of what might lie beyond that interior door taxed my imagination. Would I find skeletons stacked atop each other? Mounds of decomposing flesh? Rows of coffins?

Or had the servant’s confession to my nursemaid sprung from a desire to keep the rumour alive?

My anticipation rose to near-unbearable levels. I passed quickly through the narrow altar room, and placed unsteady fingers on the bronze latch leading to the unknown. Unlike all the other doors, which were ten times my girlish width and four times my height, this one was scarcely large enough to admit a man. I pulled it open.

Only the cold arrogance conferred by my father’s blood allowed me to repress a shriek of terror.

Shrouded in gloom, the chamber did not easily reveal its dimensions. To my childish eyes, it seemed vast, limitless, due in part to the darkness of unfinished stone. Only three tapers lit the windowless walls: one some distance from me, and two on large iron sconces flanking the entrance.

Just beyond them, his face lit by the candles’ wavering golden glow, stood my welcoming host. Or rather, he did not stand, but was propped against a vertical beam extending just past the crown of his head. He wore a blue cape, attached to the shoulders of his gold tunic with fleur de lis medallions. At breast and hip, ropes bound him fast to his support. A wire connected to one arm raised it away from his body, and bent it out at the elbow, the palm turned slightly upward in a beckoning gesture.

Enter, Your Majesty.

His skin looked like lacquered sienna parchment, glossy in the light. It had been stretched taut across his cheekbones, baring his brown teeth in a gruesome grin. His hair, perhaps luxuriant in life, consisted of a few dull auburn hanks hung from a shrivelled scalp. And his eyes…

Ah, his eyes. His other features had been allowed to shrink gruesomely. His lips had altogether disappeared, his ears become thick, tiny flaps stuck to his skull. His nose, half as thin as my little finger, had lost its fleshy nostrils and now terminated in two gaping holes, enhancing his skeletal appearance. But the disappearance of the eyes had not been tolerated; in the sockets rested two well-fitting, highly-polished orbs of white marble, on which were carefully painted green irises, with black pupils. The marble gleamed in the light, making me feel I was being watched.

I swallowed; I trembled. Up to that moment, I had been a child on a silly quest, thinking she was playing a game, having an adventure. But there was no thrill in this discovery, no precocious joy, no naughty glee—only the knowledge that I had stumbled onto something very adult and terrible.

I stepped up to the creature before me, hoping that what I saw was somehow false, that it had never been human. I pressed a tentative finger against its satin-breeched thigh and felt tanned hide over bone. The legs terminated in thin, stockinged calves, and fine, tufted silk slippers that bore no weight.

I drew my hand away, convinced.

How can you stand it, Alfonso? Don’t you want to know if it is true?

No. Because it might be.

How wise my little brother was: I wished more than anything to disremember what I had just learned. Everything I had believed about my grandfather shifted then. I had thought him a kindly old man, stern, but forced to be so by the burden of rulership. I had believed the barons who rebelled against him to be bad men, lovers of violence for no reason save the fact they were French. I had believed the servants who said the people despised Ferrante to be liars. I had heard Ferrante’s chambermaid whisper to Donna Esmeralda that the King was going mad, and I had scoffed.

Faced with an unthinkable monstrosity, I did not laugh now. I trembled, not at the ghastly sight before me, but at the realization that Ferrante’s blood flowed through my veins.

I stumbled forward in the twilight past the chamber’s sentry, and saw perhaps ten more bodies in the shadows, all propped and bound, marble-eyed and motionless. All save one.

Some six dead men’s distance, a figure bearing a lit taper turned to face me. I recognized my grandfather, his whitebearded visage rendered pale and spectral in the flickering glow.

‘Sancha, is it?’ He smiled faintly. ‘So. We both took advantage of the celebration to slip away from the crowd. Welcome to my museum of the dead.’

I expected him to be furious, but his demeanour was that of one greeting guests at an intimate party. ‘You did well,’ he said. ‘Not a peep, and you even touched old Robert.’ He inclined his head at the corpse nearest the entrance. ‘Very bold. Your father was much older than you when he first entered this place; he screamed, then burst into tears like a girl.’

‘Who are they?’ I asked. I was repelled—but curiosity demanded that I know the entire truth.

Ferrante spat on the floor. ‘Angevins,’ he answered. ‘Enemies. That one’—he pointed to Robert—‘he was a count, a distant cousin of Charles d’Anjou. He swore to me he’d have my throne.’ My grandfather let go a satisfied chuckle. ‘You can see who had what.’ Ferrante moved stiffly over to his former rival. ‘Eh, Robert? Who’s laughing now?’ He gestured at the macabre assembly, his tone growing suddenly heated. ‘Counts and marquis, and even dukes. All of them traitors. All of them yearning to see me dead.’ He paused to calm himself. ‘I come here when I need to remember my victories. To remember I am stronger than my foes.’

I gazed out at the men. Apparently the museum had been assembled over a period of time. Some bodies still had full, thick heads of hair, and stiff beards; others, like Robert, looked slightly tattered. But all were dressed in finery befitting their noble rank, in silks and brocades and velvets. Some had gold-hilted swords at their hips; others wore capes lined with ermine, and precious stones. One had a black velvet cap with a white ostrich plume, tilted at a jocular angle. Some simply stood. Others struck various poses: one propped a wrist on his hip, another reached for the hilt of his sword; a third held out a palm, gesturing at his fellows.

All of them stared ahead blankly.

‘The eyes,’ I said. It was a question.

Ferrante blinked down at me. ‘Pity you’re a female. You’d make a good king. Of all his children, you’re most like your father. You’re proud and hard—much more so than he. But unlike him, you’d have the nerves to do whatever’s necessary for the kingdom.’ He sighed. ‘Not like that fool Ferrandino. All he wants are pretty girls to admire him and a soft bed. No backbone, no brains.’

‘The eyes,’ I repeated. They troubled me; there was a perversity to them that I had to understand. I had heard what he had just told me—words I had not wanted to hear. I wanted to distract myself, to forget them. I wanted to be nothing like the King, like my father.

‘Persistent little thing,’ he said. ‘The eyes dissolve when a body is mummified—no way around it. The first ones had shut eyelids over empty sockets. They looked like they were sleeping. I wanted them to hear me when I spoke to them. I wanted to be able to see them listening.’ He laughed again. ‘Besides, it was more effective that way. My last “guest”—how it terrified him, to see his missing compatriots staring back at him!’

I tried to make sense of it all from my naive perspective. ‘God made you King. So if these men were traitors, they went against God. It was no sin to kill them.’

My remark disgusted him. ‘There is no such thing as sin!’ He paused; his manner turned instructive. ‘Sancha, the miracle of San Gennaro…it almost always occurs in May and September. But when the priest emerges with the reliquary in December, why do you think the miracle so often fails?’

The question took me by surprise; I had no inkling of the answer.

‘Think, girl!’

‘I don’t know, Your Majesty…’

‘Because the weather is warmer in May and September.’

I still did not understand. My confusion registered on my face.

‘It’s time you stopped subscribing to this foolishness about God and the saints. There’s only one power on earth—the power over life and death. For the time being, in Naples at least, I possess it.’ Once more, he prodded me. ‘Now, think. The substance in the vial is at first solid. Consider the fat on a pig, or a lamb. What happens to that fat if you roast the animal on a spit—that is, expose it to warmth?’

‘It drips down into the fire.’

‘Heat turns the solid into a liquid. So perhaps, if you took the reliquary of San Gennaro from its cool, dark closet out into the Duomo on a warm, sunny day and wait for a while…il miracolo e fatto. Solid to liquid.’

I was already shocked; my grandfather’s heresy only deepened that sensation. I recalled Ferrante’s cursory attitude towards all things religious, his eagerness either to absent himself from or to be done swiftly with Mass. I doubted he ever knelt at the little altar which led to the chamber housing his true convictions.

Yet I was simultaneously intrigued by his explanation of the miracle; my faith was now imperfect, threaded with doubt. Even so, habit was strong. I prayed silently, speedily to God to forgive the King, and for San Gennaro to protect him despite his sins. For the second time that day, I prayed for Gennaro to protect Naples—though not necessarily from crimes wrought by nature or disloyal barons.

Ferrante reached with his bony, blue-veined hand for my smaller one, and squeezed it in a grip that allowed no dissent. ‘Come, child. They will wonder where we are. Besides, you have seen enough.’

I thought of each man within the museum of the dead—how they must have been introduced by my gloating grandfather to the fate awaiting them, how the weaker ones must have wept and pleaded to be spared. I wondered how they had been killed; certainly by a method that left no trace.

Ferrante held the taper high and led me from his soulless gallery. While I waited inside the altar room as he closed the little door, I reflected on the clear pleasure he took from the company of his victims. He was capable of killing without compunction, capable of savouring the act. Perhaps I should have feared for my own life, being an unnecessary female, yet I could not. This was my grandfather. I studied his face in the golden light: it wore the same benign expression, possessed the same ruddy cheeks with their latticework of tiny broken veins that I had always known. I searched his eyes, so like mine, for signs of the cruelty and madness that had inspired the museum.

Those eyes scrutinized me back, piercing, frighteningly lucid. He blew out the taper and set it upon the little altar, then retook my hand.

‘I will not tell, Your Majesty.’ I uttered the words not out of fright or a wish to protect myself, but out of a desire to let Ferrante know my loyalty to my family was complete.

He let go a soft laugh. ‘My dear, I care not. All the better if you do. My enemies will fear me all the more.’

Back through the King’s bedchamber we went, through the sitting room, the outer office, then last of all the throne room. Before he pushed open the door, he turned to regard me. ‘It’s not easy for us, being the stronger ones, is it?’

I tilted my chin to look up at him.

‘I’m old, and there are those who will tell you I’m becoming feeble-minded. But I still notice most things. I know how you love your brother.’ His gaze focused inward. ‘I loved Juana because she was good-natured and loyal; I knew she would never betray me. I like your mother for the same reason—a sweet woman.’ He drew his attention outward to study me. ‘Your little brother takes after her; a generous soul. Worthless when it comes to politics. I’ve seen how devoted you are to him. If you love him, look out for him. We strong have to take care of the weak, you know. They haven’t the heart to do what’s necessary to survive.’

‘I’ll take care of him,’ I said stoutly. But I would never subscribe to my grandfather’s notion that killing and cruelty were a necessary part of protecting Alfonso.

Ferrante pushed open the door. We walked hand-in-hand back into the Great Hall, where the musicians played. I scanned the crowd for Alfonso, and saw him standing off in a far corner, staring owl-eyed at us both. My mother and Isabella were both dancing, and had for the moment altogether forgotten us children.

But my father, the Duke of Calabria, had apparently taken note of the King’s disappearance. I glanced up, startled, as he stepped in front of us and stopped our progress with a single question.

‘Your Majesty. Is the girl annoying you?’ During my brief lifetime, I had never heard the Duke address his father in any other fashion. He looked down at me, his expression hostile, suspicious. I tried to summon the mannerisms of pure innocence, but after what I had seen, I could not hide the fact I had been shaken to the core.

‘Not in the least,’ Ferrante replied, with good humour. ‘We’ve just been exploring, that’s all.’

Revelation, then fury, flashed in my father’s beautiful, heartless eyes. He understood exactly where my grandfather and I had been—and, given my reputation as a miscreant, realized I had not been invited.

‘I will deal with her,’ the Duke said, in a tone of great menace. He was famous for his vicious treatment of his enemies, the Turks; he had insisted on personally torturing and killing those captured in the Battle of Otranto, by methods so inhuman we children were not permitted to hear of them. I told myself I was not afraid. It was unseemly for him to have me, a royal, thrashed. He did not realize that he already imposed on me the worst punishment possible: he did not love me, and made no secret of the fact.

And I, proud as he, would never admit my desperate desire to gain his affection.

‘Don’t punish her, Alfonso,’ Ferrante said. ‘She has spirit, that’s all.’

‘Girls ought not to have spirit,’ my father countered. ‘This one least of all. My other children are tolerable, but she has done nothing but vex me since the day of her birth—a day I deeply regret.’ He glared down at me. ‘Go. His Majesty and I have matters to discuss. You and I will speak about this later.’

Ferrante let go my hand. I made a little curtsy and said, ‘Your Majesty.’ I would have run full tilt had the Hall not been filled with adults who all would have turned and demanded decorum; as it was, I walked as swiftly as possible over to my waiting brother.

He took a single glimpse at my face and threw his arms about me. ‘Oh, Sancha! So it is true…I am so sorry you had to see. Were you frightened?’

My heart, which had grown so chilled in the presence of my two elders, thawed in Alfonso’s presence. He did not want to know the details of what I had witnessed; he wanted only to know how I had fared. I was a bit surprised that my little brother was not more shocked to learn that the rumour was true. Perhaps he understood the King better than I did.

I drew back, but kept my arms entwined with his. ‘It was not so bad,’ I lied.

‘Father looked angry; I fear he will punish you.’

I shrugged. ‘Maybe he won’t. Ferrante didn’t care a whit.’ I paused, then added with childish bravado, ‘Besides, what will Father do? Make me stay in my room? Make me go without supper?’