Полная версия

The Beechwood Airship Interviews

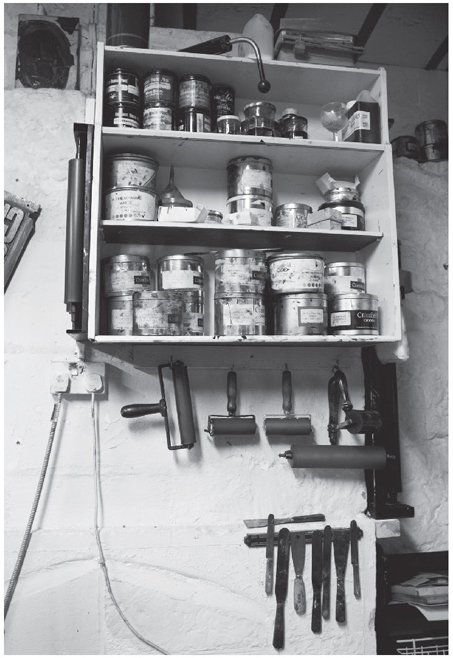

He up-ends it. Nothing happens.

‘I could probably leave it upside down for an hour before any came out; but some inks are thinner than others. White is a problem.’

He opens a tin of white and lays it sideways on the bench. An ominous bulge begins to form, like angry custard.

‘As you can see, it’s almost able to flow. White is a notoriously difficult colour to work with because white, as a pigment, is lousy and getting enough of it into stuff is very difficult. That’s why, if you ever see white type on black in a magazine it was almost certainly printed black onto white paper rather than the other way round.’

How is white ink made?

‘It’s usually titanium and other stuff – aluminium oxide sometimes, depending upon what you want. Most of the pigments are inorganic chemicals.’

Gone are the days of beetles for blue and suchlike?

‘Um, mostly. (Laughs)

I don’t know what some of the pigments are that they use. Having said that, I bought all these tins of ink for the same price and some had noticeably less in than others because the pigments involved were just that bit more expensive. To this day, a kilogram of blue will cost you more than a kilogram of yellow.’

• • • • •

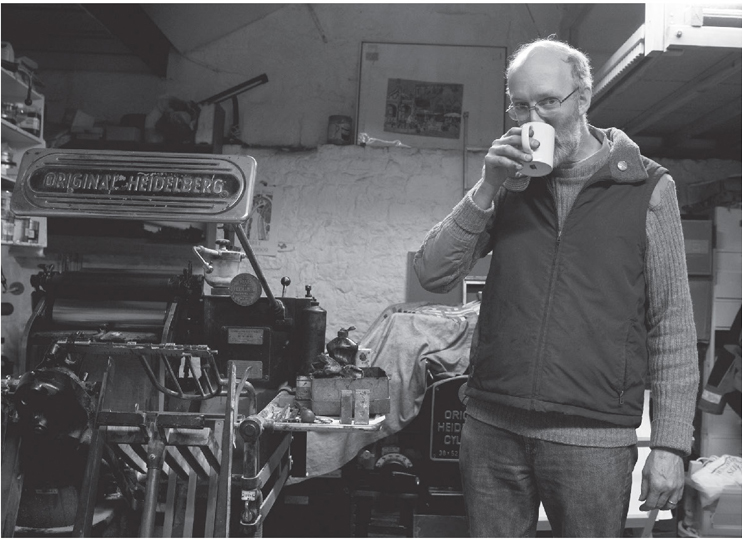

At this point we pause for more coffee and a Penguin biscuit. Richard sits framed by a stacked tower of drawers that rise floor to skylight, each one partitioned into myriad cells – packed with an unseen type, filed away; dormant words.

Tall, bearded, an L.S. Lowry figure in jumper and gilet, he seems quietly amused by most things – I suppose he’s what people would call diffident, but actually I think it’s another facet of his economy – he’s not one for small talk, reserves judgement. There’s nothing superfluous about him – he’s lean. A spare man.

‘It’s actually quite rare to find someone who is interested. As you’ve probably worked out by now, I’m interested in the technicalities of it. That’s what I get excited about.

The images are great and it’s nice working with people like Stan but it’s the whole business of “How does it work?” that actually excites me.’

Do many people track you down because you work with Stanley?

‘No, thankfully not, somehow it hasn’t happened. He’s very fair about giving me billings on things that I have helped him with but no one seems interested in me, for which I’m eternally grateful. But then, I’ve been to one or two of his launch events and he seems to have a habit of wandering around, not actually telling people who he is.*

Having said fiercely that I’m not an artist, I’m actually a scientist by training. I spent the best part of twenty years working for a publisher in various editorial functions producing maths and science books. I like printing because I can understand how it works – if this bit doesn’t work it’s because that bit isn’t connected to the lever that makes it wiggle … and I can then do something about it. I’m very happy with this lot and if something goes wrong I can fix it.’

Where did you get your presses?

‘Well, the Albion in the corner came from an artist, a genuine artist, who made linocuts and worked at the art school at Banbury. He was getting on to retirement and needed to get rid of it so he advertised in the back of a magazine that I read and I bought it from him.’

Can it be taken apart?

‘It can to a certain extent, yes, but the main casting remains unfeasibly heavy and awkward to move; and while nobody knows what Gutenberg’s press looked like, it was probably very similar – except of course that his was made out of wood rather than metal.

While letterpress continued they were very useful, practical things – they made excellent proof-presses. So, rather than locking something up in a machine forme* and all that – particularly on very large printing machines, terribly tedious – you could ink these by hand and print a sheet or proof very quickly.

‘The 1965 platen came from a printer in Oxford who was closing down. He’d made it to the age of eighty-something and his second replacement knee didn’t really take to it so he decided it was time to retire. I’d got to know him and, when it came time for the machine movers to come and take this away, he suggested that I had a word with them. They were essentially taking it away to recondition it and sell it on – probably for die cutting and blind embossing and that sort of thing. I think I gave them about £400 for it and they took it out of his workshop and dropped it at my house a mile up the road. £400!’

What is it worth now?

‘£400!’ (Laughs)

Really?

(Still laughing) ‘There’s a limited market for them; a limited number of people who know how to use them.

This 1958 Heidelberg came from a private press in Marlborough. I’m very lucky to have got it. They used it very little but kept it in very good condition so it hasn’t done many miles.’

It looks in amazing shape.

‘The longevity of these machines is mind-boggling; if you look in the back of trade magazines you’ll see “Heidelberg, six colour – only 70 million impressions.” If you look after them, oil them and replace the odd bits that do wear out they just go on and on. The one I had before was from 1940-something and it was a little rattly but, if you treated it with a small amount of care it would work absolutely fine. The one I used at school was built in 1920-something – that was definitely on the wrong end of rattly but still worked quite well.’

I imagine Richard using the old school press. I wonder what he was like as a child. He seems to embody a stoic enjoyment; a half-amused smile of concentration on his face. The flat smell of ink on his hands.

‘It’s interesting to see the reaction of people who do come in here. I’ve had quite a few in who used to work in the printing trade and they say, “Ooh, wonderful! The smells of ink!” and so on, and some people get excited by all the curiously shaped lumps of machinery and some get excited about all the bits of woodcut and type and I sort of understand that but what excites me is that “It’s machinery! It works! I can do something with it!”

People get a bit put out, frightened even, when I don’t react in the right way; when I don’t get enthusiastic about the “incredible texture and quality” of something … but I’m a creature from a mechanical world, really. That’s what excites me.’

STANLEY DONWOOD (1967– ) is a British artist and writer, known for his work with the band Radiohead. Since 1994 he has produced all artwork for the group in collaboration with lead singer Thom Yorke. He has also written the short story collections Slowly Downward: A Collection of Miserable Stories (2005), Household Worms (2011) and Humor (2014).

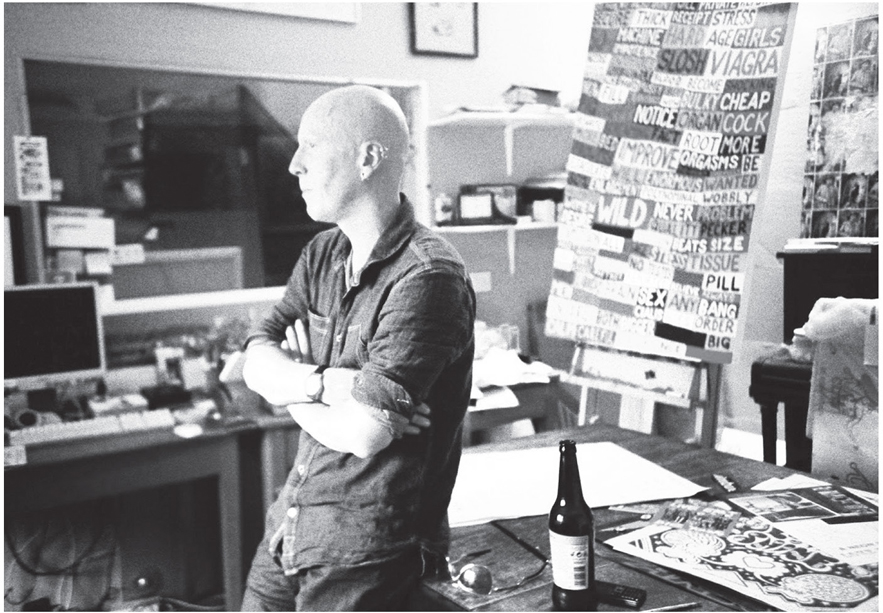

STANLEY DONWOOD

Derelict dance hall, Bath

March 2009

The first time I met Stanley Donwood he was not in his element. Hosting the simultaneous launch and closure of his record label, Six Inch Records,* at a trendy London bar he stood apart from his guests; nipping outside for furtive roll-ups whenever possible, eschewing the venue’s lava-lamp paint scheme and 8’ egg-shaped isolation booth latrines.

When he had to interact and address the crowd to introduce a band he stood onstage uneasily. A pregnant cough. A pause; another cough before breaking into a run-up of ‘Um … er … OI!’

The night wasn’t his idea, I suspected.

He’s not a man for the spotlight, Stanley.

He’s much more likely to be the man taking apart the spotlight with a spanner … or a hammer.

He has the air of a man in a spot of difficulty; a man who’d much prefer to be elsewhere, perhaps.

He’s not even really called Stanley, you know; not even that’s right.

‘I’ve got a rubbish pseudonym. “Stanley Donwood”!? Rubbish.’

I approached him at the trendy launch and introduced myself. Yes, I’m the chap with the airships, we establish, and he’s the chap with the bowler hat and the pseudonym; no, it wasn’t his idea.*

• • • • •

Stanley Donwood, whoever he might be, is responsible for Radiohead’s* aesthetic, artwork and labyrinthine websites. Millions of people have his work in their homes, hundreds of thousands would recognise the pointy-toothed bears that have become something of a trademark. He has accidentally become very popular and his work is in demand. He is adept in many media, constantly evolving and adapting. He exhibits all around the world. He has won awards.*

He’s not sure how he feels about any of this, preferring to keep a low profile and not give interviews … for a long time people assumed he was an alias of Radiohead’s singer, Thom Yorke; but he isn’t.

‘That’d be nice, though. I’d have better hair.’

Stanley’s studio is an old dance hall. Where once it thrummed to the tunes of the day, it now echoes, abandoned and cavernous. The floorboards creak, the windows are cracked and icy, ivy grows through the frames. The only light in the place shines feebly – up a flight of wooden stairs that groan – a small office with a workshop beyond.

He beckons me in and shuts the door, apologising for the extreme cold.

‘All studios are cold. It’s the law.’

Is it always so cold?

‘Yes.’

And you always work here?

‘At the moment, yeah. I paint in a barn in Oxfordshire as well but that’s a bit more rudimentary than this, it’s … well, it’s a barn. There’s a wood burning stove so when that’s going it’s quite nice but most of the time it’s like being outdoors.’

Do you work with other people? I mean, will members of the band chip in?

‘Oh yeah! For instance, with In Rainbows* I’d have whatever stage the artwork had got to cycling on all the computers around the studio and the band would say, “Oh I like that one and I like that one.” So, over time, I could say, “Right, so that’s where it’s going.” We’d all talk about it and come into a sort of creative consensus about what was working well.

It was evolving as the music was evolving … and no record label! We were all working towards a deadline which became more concrete as time went on because we’d got things to manufacture, we had to book the factories to press the records and all that kind of thing, and all anonymously.

If the next thing works in that sort of way, that would be great. I’m sure it won’t because they’re never the same.

Hail to the Thief,* the one before, that was me in my barn with huge paintings around the walls, working on several at the same time, and the nice thing with that one was that I’d got this rubbish CD boom-box thing in there with me and the band would come into the barn in the evening – which is across the way from their recording studio – with the latest whatever-they’d-done on CD and play it and, because the barn’s all wood and vaguely insulated with plywood, it just sounded really cool! So they would come over to have a beer and listen to what they’d done. Outside, away from the brilliant speakers, to hear it more as it was going to be heard.’

• • • • •

Stanley has a record player in one corner of the room. While we talk he plays a selection of well-thumbed punk and post-punk records – Bauhaus, Magazine and Sex Pistols. Cold as it might be, the studio is a den, stuffed with collected ephemera; test prints and clippings on the wall, an old piano, a screen printing table at the back with tins of ink and paint stacked behind; a painty carpet and a painty sink. Above a wide window overlooking a courtyard is written:

FIRE EXIT

BASH SIDE BITS OUT WITH HAMMER PULL WINDOW OUT AND BE VERY FUCKING CAREFUL

Stanley puts the kettle on and I unpack some of the Radiohead records I’ve brought along as reference.

He returns with tea as I place the My Iron Lung EP* on the table.

‘Oh God! (Turning it over in his hands) I can’t remember this at all! This was the first thing though … we had all this footage Thom had shot on tour and we ran it through his telly and took photographs of it. I liked the men standing around for their meeting – they were Osaka businessmen, I think. Lots of legs, yes … we didn’t really know what we were doing.’ (Laughs)

You don’t generally do interviews, do you?

‘Not loads, no. I prefer to do them over email really ’cos I feel rather inarticulate when I’m speaking – lots of “ers” and “ums” and “hmmms”. Whenever I’ve done it, talked to someone for an interview, I always feel like such a twat afterwards. I think, “Why did I say that? I should have said something else.”’

Bill Drummond told me he wasn’t happy being called an artist for a long time. Was that an issue for you?

‘I don’t mind saying I’m an artist now. I used to say I was “sort of an artist” but as you go on you meet people, grown-ups, adults, and they say, “What do you do?” and you can’t really get away with that so I just say, “I’m an artist” and it covers everything.

“Commercial Artist” I quite like. That’s what graphic designers used to be called; artists for hire. I don’t mind being for hire! (Laughs)

In a different world I’d be painting pub signs; doing something useful. I want to be, you know, a bit useful, because I’m a Jack-of-all-trades, master of absolutely none.

I’d love to be actually good at something, you know? Do one thing. That would be great!’

Richard Lawrence is very good at one thing.

‘Richard is, yes, and I think this is why I get on so well with him – because he says, “I’m a technician. I’m not an artist.”’

He does! Your relationship seems very complementary in that he’s the practical print mechanic, able to make your ideas about lino, text and printing happen pretty quickly.

‘He really can, yeah. I wouldn’t be able to work those bloody machines, they terrify me!

When I went to art college, the first people that I connected with were the technicians. There was a guy called Tony who was the print technician and we got on straight away; he was a real local boy from Devon and while all the tutors were talking about stuff from their sixties educations which had nothing to do with what I was about, he was someone who actually knew what he was doing and how to do it – that was much more interesting to me.’

Were you working as a ‘sort of artist’ before you began work with Radiohead?

‘Not “working”, no. I was officially a job seeker – £39.70 a week. That was alright for a while. I was a clandestine artist – not a spray-can artist, I didn’t have the means. I had a paint pot and a brush.’

Then you got the call.

‘Yeah, “Do you want to have a go at doing a record sleeve?” and I said, “Yeah!?” I didn’t know how to do it. I know how to do it now because I’ve done it lots of times. I’ve learnt on the job, as they say …’

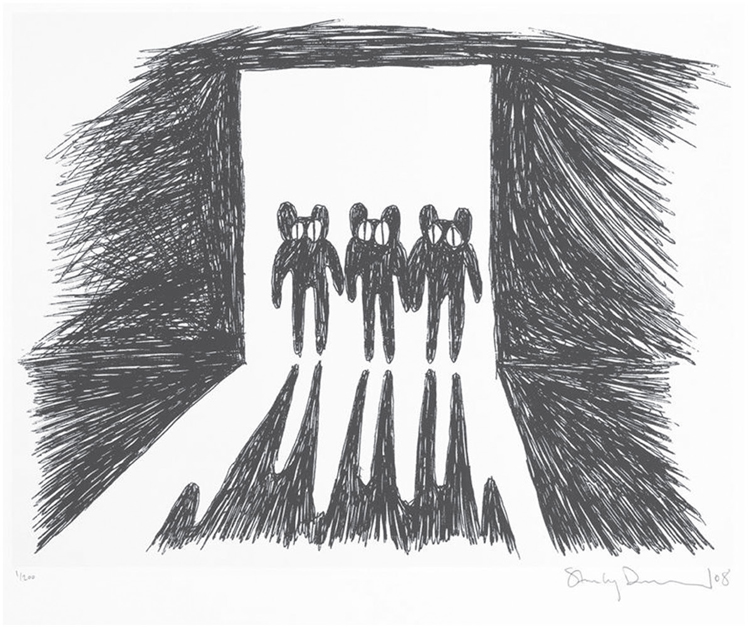

I want to ask you about the bears; they’re your bears, they were on the Six Inch Record sleeves, but they’re Radiohead Bears to most people.*

‘I’ve been working with them for ages. I’ll use my stuff in their stuff. It’s hard to separate; I mean, it doesn’t separate – I do their artwork. Their artwork is my artwork.

The bears began when my eldest daughter was quite little, about one, one and a half – they wake up devilishly early in the morning and you’re in this weird state, it’s dark and there’s nothing to do but make a cup of tea. I used to draw stories and tell them at the same time. I was telling a story to do with toys, abandoned toys … it’s really bad when I think about it, luckily she couldn’t understand …’

Was it a bit dark?

‘It was a bit dark, yes – all the toys that are discarded by adults, sitting in this attic, got really fed up and so these cute teddy bears came down and ate the grown-ups … scary bears who’d started off nice and then became (bares teeth and howls) “Grawww!!!”

And that was it, it was just a drawing that was in a sketchbook and then I drew a load of them marching down a dark alley and then I started using them with Radiohead – the website first and then on a t-shirt and then it turned into all sorts of things.’

Around the time of Amnesiac* I remember you put out a very scribbly poster of bears flying through a city and people looking up concernedly …

‘That’s Thom’s drawing. He drew that; that was weird that one. At that time there was a lot of faxing back and forth “Phish, pheee, phew”; he’d send a fax, I’d draw on it and send it back, but that particular drawing of the flying bears, I’d done one at the same time – we did them on the same night, it was really weird – without telephoning or anything like that. We were both having some sort of mental flood or storm or something. I remember it intensely; drawing like mad with a biro, almost going through the paper with it. I think I scanned and faxed it to Thom and he scanned what he’d done and sent it back and they’d both been done at the same time and they were pretty much of the same level of biro intensity … that happens quite a lot with us, we work together a lot and do this thing of swapping where I’ll do something and then say, “You do something” and he’ll do something and say, “Now you do something”, so we’ll pass it backwards and forwards. We’ve painted large canvases where one person will do something until the point where you think, “I’m finished” and then the other person would go along and “Shhhhhhh” do something to it. We’ll basically fight over the ownership of the canvas until one or other of us owns it – which is a hard thing to do but, you know, you’ll get to a point where you think, “Right, that’s mine now, I’ve got it.” It’s like fencing but with a piece of artwork.

We’ve done it remotely with fax machines and lately with emailing.’

Do similar battles happen with the band musically, do you think?

‘I really don’t know. I hear them making music and some of the stuff for Kid A.* (Laughs) … I mean, Kid A is apparently quite dark but earlier versions of it were really dark – much more upsetting really … they got rid of some of the bits, some sections and sounds which were just too much but I … I’m a sloganeer, I’m into sorta like “BAM BAM BAM!!!” but they’re into a more musical art thing, something that will last and something that will work in different situations, so certain things they did, I said, “That’s brilliant! You’ve got to keep that!” but they decided, “No, it won’t work in time. It works now but it won’t work in a year’s time …”

I don’t have the same level of quality control because, I mean, with the way that I’ve worked with Radiohead and so on, there’s five of them and Nigel.’*

Six?

‘I would say 5 + 1 rather than 6.

With the artwork there is me and Thom, which is very different to 5 + 1. We’re 1 + 1, which, compared to 5 + 1 … what comes out of that is very different. I mean, obviously, we don’t go ahead with stuff if the other members of the band aren’t comfortable or happy with it.’

Has that ever happened?

‘No … although I’ve gone wrong a few times.

With In Rainbows I was going to do all this architectural stuff with the software that’s used to create optimum car parking spaces …’

The 2006 tour posters and merchandise were grey, I remember.

‘Yeah. “Any colour so long as it’s grey.” All the t-shirts were grey – it was possibly one of the most insulting things I could have done. Immediately afterwards we set up in Tottenham House, this decaying stately home near Marlborough, to work … and I’d been there for two days or something – had been obsessed by this book The Long Emergency by James Howard Kunstler* – was in this dreadful nihilistic state, preoccupied with car parks and all that sort of thing, thinking, “There. Bam. Right. This is how it’s going to be” … but they were playing the music and it was the most organic, spiritual, sexual, sensual, beautiful thing that I’d heard them do and I realised that what I was doing was completely wrong and that my head, my mind, my response, had gone awry.’

How did the In Rainbows artwork evolve then – the discbox and the ‘pay what you want’ aspect of the digital release?

‘They’d been thinking how to put the new record out. The idea of people paying what they wanted for it was a bit of a reaction to the way that people who like music are treated by the record industry – if you can imagine such a thing as this overarching authority: “The Music Industry”.

They treat people like, if not actual criminals, potential criminals. All this stuff – targeting people who download music for nothing, what happened to Napster.* It was a reaction to the way the industry assumes people are going to steal music and has created a legal and software mechanism to prevent that. So there was this idea, “Okay, let’s put the record on the internet and say you can pay what you want for it, pay what you think it’s worth – and some people won’t pay anything, some people will pay something,” which was a bit of a gamble, really. A huge gamble.

So the band and management said, “Okay, let’s do it for nothing,” and, to me, “Can you make us something that’s worth about forty quid?” and I thought, “That’s quite a fucking challenge!” (Laughs) “How can I make something that is essentially wrapping paper worth £40?” because, you know, I’d been doing this thing with EMI and they were principally releasing compact discs – horrible, clattery boxes which I hate and have, to my mind, really degraded what record packaging is.

When I was a kid growing up, I would buy records because I liked the sleeves and I would spend ages looking at the sleeves and poring over the sleeve-notes and the lyrics.’

You’d made unusual sleeves prior to the discbox, though: the Hail to the Thief foldout map and the Amnesiac book …

‘Yes, but they were always “Special Editions” and I had to really hassle the record company to do it. They really didn’t like doing it. The people that I dealt with first off were great but there would be people higher up who’d say, “Well, you know, can you reduce the number of pages?” It was always very hard to get it done.’

Without compromising the idea away.

‘Exactly. It was always a question of “How far can you push them?”

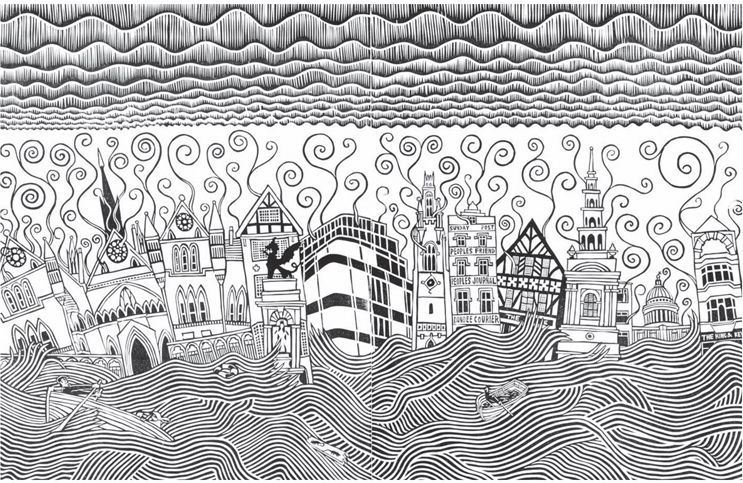

Kid A sounded to me like a message left on an answerphone that you received too late to do anything about, but Amnesiac was something else, it was something found when clearing a house, something in an attic, an old book in a drawer, a fragment – something left behind, the meaning of which had been lost.’

The Amnesiac book always struck me as fraught, as you say. Cross-hatching, layered detailing, out of focus, pixellated images – so much work in it, yet its meaning is a mystery; lost and unloved, like the toys in the attic.

‘I spent a long time in London working on it. Walking in London and reading books about London. I found this book called The House of Dr Dee by Peter Ackroyd* and he mentioned Piranesi,* who I’d never heard of, so I went out and found out a bit about Piranesi and I started copying Piranesi’s drawings with a biro because I wasn’t quite sure about copyright. Peter Ackroyd, Iain Sinclair and Stuart Home … Michael Moorcock’s written some brilliant books about London. King of the City* is fantastic! (Begins turning the pages of the Amnesiac book) God, yes, and the bull …’

The Minotaur?

‘Mmm, Mithras, labyrinthine structures and the idea of a city being a maze or a prison – Piranesi’s imaginary prisons … I would get the train up to London for the day. I did it again and again, doing something that I’ve since found out Bill Drummond does, which is to write a name or a word across a city and then walk the letters … but I was trying to make a film as well and I did make a film in the end, to do with the bull. I think I went a bit mad, to be honest. I think I developed an obsession, looking back; but this idea of bulls … Smithfield Market and Smithfield Fair and its ancient past of bull running. I imagined that the cattle would be taken there, then they’d have this ritual thing where they would drive a bull down to the Thames and kill it and have some sort of horrible sacrifice thing; something to do with bridges and the little beaches you get on the Thames … and I made a film.