Полная версия

The Beechwood Airship Interviews

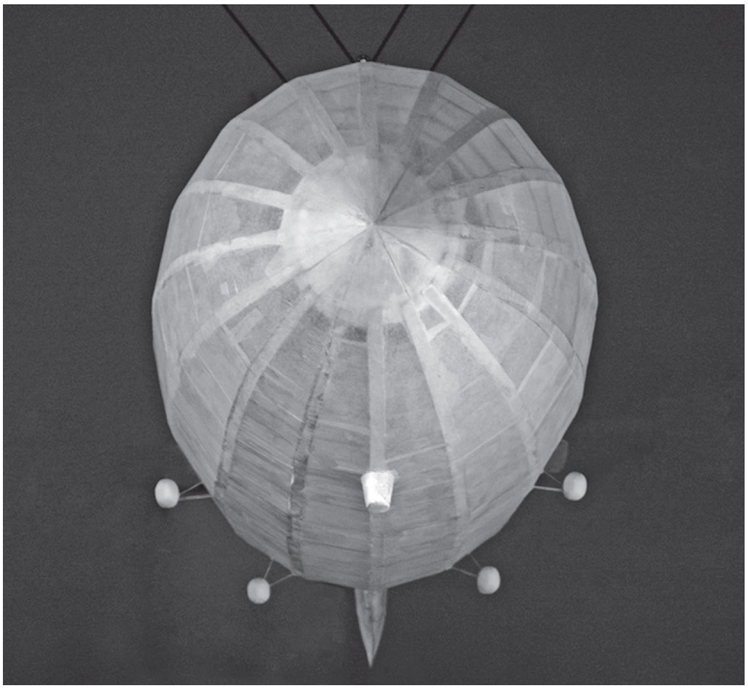

Looking down the beech laths at the scarf joints, I felt the calm assurance of the materials and saw the influence of Richard and Colin in Henley-on-Thames and my father back in Bristol. The airship had put me in touch with them and articulated their knowledge better than words. The process was a language, lucid and succinct. It had an integrity.

I had faith in the wood and glue.

On 15 August 2007 I made the following note in my diary:

Today the bar paid for a set of ropes and pulleys and hired a scaffold tower.

I keep finding notes I’ve written about ‘People who know what they’re doing.’

I work here, in this room. The airship is site-specific.

The room is the space I respond to.

Does this happen to other people?*

• • • • •

The scaffolding tower was assembled one weekend shortly before the start of the new school year. From the top it was clear that the eaves were a lot higher than they seemed from the bar far below. Three of us scaled the gantry to hang ropes and thread the pulleys and shortly afterwards the airship was winched into the air for the first time accompanied by a blast of ‘When the Levee Breaks’.*

It was up.

From beneath, its lines merged and intercut the wood of the roof, putting me in mind of Orozco’s Mobile Matrix, a suspended whale skeleton,* and as the concentric graphite circles drawn on those bones radiated out, overlapped and distorted, so the beams moved through the cage of beechwood above our heads now. The few of us there in the moments after it was raised walked up and down below as the airship swam.

Later I sat on the stage at the back of the hall and looked at it for an hour or two, watching it settle in the ropes. It was up; unpapered and naked for now but that could be addressed over time.

But the important thing, as Rob pointed out, was that the stage was now freed up for the pool table because, say what you like about arty kids in an arty bar, they loved their pool: ‘You know, given the choice between an arty airship and pool …’

Luckily such a nightmarish choice was never forced upon them.

The new term started and I went back to my MA, papering the airship on Sunday mornings with tissue paper donated by Habitat.* I was helped in this task by Virginie Mermet, a brilliant French girl.*

We’d arrive early and open all the windows to ventilate the stale ale air before making tea and lowering the airship down. Tissue was cut into strips and applied with aircraft dope – a varnish that tautened and strengthened the paper as it dried while giving us headaches and mild hallucinations.

During these mornings we’d talk about ideas of artists and space and listen to Klaus Nomi.* Virginie was of the opinion that all artists create and respond to a space, be it site-specific sculpture like the airship or an environment attuned to making work. We spoke about photographs we’d seen of Francis Bacon’s studio and Roald Dahl’s shed, concepts of theatre and atmosphere; the idea that a resonance of creativity can remain in a building long after the people have gone and the function altered.

Kitchens, boat yards, studios, halls, sheds, rehearsal rooms, cellars, theatres, roofs, gardens, landscapes, vehicles – inspiring and facilitating artistry.

Some spaces must bear witness to a process while others stimulate it – become steeped in it. While some buildings evolve over decades into a perfect working environment, others are built for that purpose from scratch, others will be a compromise; some permanent, some fleeting, some known about and public, some private, even hidden.

That night as an experiment, I wrote a few pages about the broadcaster John Peel. Under the heading ATMOSPHERE, I recalled my second-year house at university; Thursday night, a large cold bedroom where the living room should have been. A desk, a set of shelves, a dicey gas fire, a bed, a wardrobe.

I’m sat at the desk in a thick jumper, illuminated by a balanced-arm lamp and the flicker of a radio set handed down from my mother – bought during the three-day weeks of the seventies because it could take batteries.

I’m listening to John Peel.

Thursday was not a pub night, Thursday was the night John broadcast his programme direct from his Stowmarket home, Peel Acres. Thursdays were sacrosanct. I remember taping Mono, The Black Keys and Four Tet sessions, listening with my finger hovering over the red button on the deck.

My diary of 13 May 2004 records that John played four session tracks by The Izzys and I enjoyed them very much. He opened the show with the greeting ‘Hello, brothers and sisters, and welcome to Peel Acres’ – very much the spirit behind those Thursdays; he was welcoming the audience into his home, where he sat playing tracks he thought we might like to hear – something new. Something by Jazzfinger or The Fall, say; the jet-wash of Part Chimp or The Izzys in session covering Richard and Linda Thompson.

Amazing to think how intimate it all felt – a man in his house in conversation with the world but broadcasting to you. A public service.

I remember the quiet of my room then, the crackle of the radio and the feeling of connectivity.

John Peel died in October 2004.*

In 2008 I wrote to his wife, Sheila Ravenscroft:

‘Perhaps the most interesting spaces grow up and around the person working within them. The longer this project* goes on, the more I think of John’s programmes from Peel Acres and recall the way the atmosphere of his studio seemed to percolate out into my room; the wonderful conversational way he had of speaking, how it fostered a world and set of associations that continue to inform what I’m writing today.’

• • • • •

In his book Waterlog, Roger Deakin describes a seemingly impossible swan dive made by a market-worker in the 1920s from the copper turret of the Norwich art school, over Soane’s St George’s Street Bridge and into the River Wensum.

A friend lent me the book towards the end of my degree and I raced through it, drinking up the words on water, wild swimming and landscape. A few minutes after discovering the Norwich nosedive passage, I was stood on the same bridge, text in hand, eyes skyward, trying to join the dots – turret, bridge, river. Copper, sky, Wensum – but the orbit did not fit.

I went back to my work on the airship, disbelieving – imagining the lad Goodson arcing, plunging head first and arrow-like – aiming at the water, his eyes brim-full of bridge.

I returned at lunchtime but the bridge was no thinner than before.

Did Roger Deakin stand here too? I wondered. Did he weigh the thing up?

Waterlog and Deakin’s subsequent book, Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, suggested a course beyond art school.

Writing in 2010, his friend Robert Macfarlane described him as

‘a film-maker, environmentalist and author who is most famous for his trilogy of books about nature: Waterlog, Wildwood and Notes from Walnut Tree Farm. I say “nature”, but his work can perhaps best be understood as the convergence of three deeply English traditions of rural writing: that of dissent tending to civil disobedience (William Cobbett, Colin Ward), that of labour on the land (Thomas Bewick, John Stewart Collis), and that of the gentle countryman or the country gentleman, of writer as watcher and phrenologist (Gilbert White, Ronald Blythe).’*

I had a lot of questions, had gone off piste with my MA to fill gaps in my heuristic knowledge and in so doing become convinced that something was amiss and the answers lay elsewhere, in the heads and hands of people at work.

Roger Deakin walked out to meet the people who knew – who swam, worked wood, dwelt and engaged with the land. Meeting with people in the spaces where they worked and lived, he found communion and kinship. Perhaps I, in light of the Beechwood Airship, could do the same and find some resolution … because the postmodern doublethink of the art school seemed a very lonely thing – a vacuum occasioned to funnel and mould the kids in a system where talk of aesthetic judgement is muted and neutered, shrugged off as subjective.

Such a cheap trick! A spiteful closing down of the cosmos and, I couldn’t help but think now, having clashed against the axioms of the institution, that their dogma was self-serving and unfit to underpin a job of work in the world beyond their walls.

I knew of graduates turned out as graphic designers with almost no knowledge of its history – the roll-call: Brody, Beck, Oliver, Saville, Kare and Scher passing without a flicker – set up to be a caricature with no depth to their knowledge beyond a syllabus which ticked the school’s boxes – eggshell graduates who’d only been pressed top down.

But then, perhaps this does the tutors a disservice, perhaps it wasn’t their fault – maybe they were under pressure to deliver a certain sort of course – perhaps the onus should be on the student to broaden their knowledge. Shouldn’t a degree be all-consuming? The past and present insatiably mined out, the future dreamt, the vocation so pressing that each new contextual source is gorged? But I knew from my own encounters that students were being dissuaded from going too far away from their prescribed course remit. Peregrination was not encouraged, cross-course collaboration dissuaded – at an art school! Surely that was wrong or was I being unreasonable?

No. You need more. You need enough rope to either hang yourself or create something great. And sometimes you need to get out on the road and discover it, physically seek and experience it for yourself – whatever that is.

Take risks. Get your hands dirty.

Bill Drummond’s totemic GET YOUR HAIR CUT and the MAKE SOUP that replaced it seemed a good place to start.

Where did he work? I wondered.

The final weeks of art school found me serving rowdy intemperance to student types on weeknights while Sundays passed in quiet concentration, Virginie and I lying side by side on the floorboards of the SU bar: papering the airship, strung out on psychotropic varnish fumes, listening to Klaus Nomi.

BILL DRUMMOND (1953– ) is a Scottish artist, musician and writer who came to prominence in the 1980s with his band The KLF. He achieved notoriety after burning one million pounds in cash as part of his art project the K Foundation. He is the author of several books and is the founder of countless art, music and media projects as well as the writer of two solo albums.

BILL DRUMMOND

St Benedicts Street, Norwich

Summer 2007

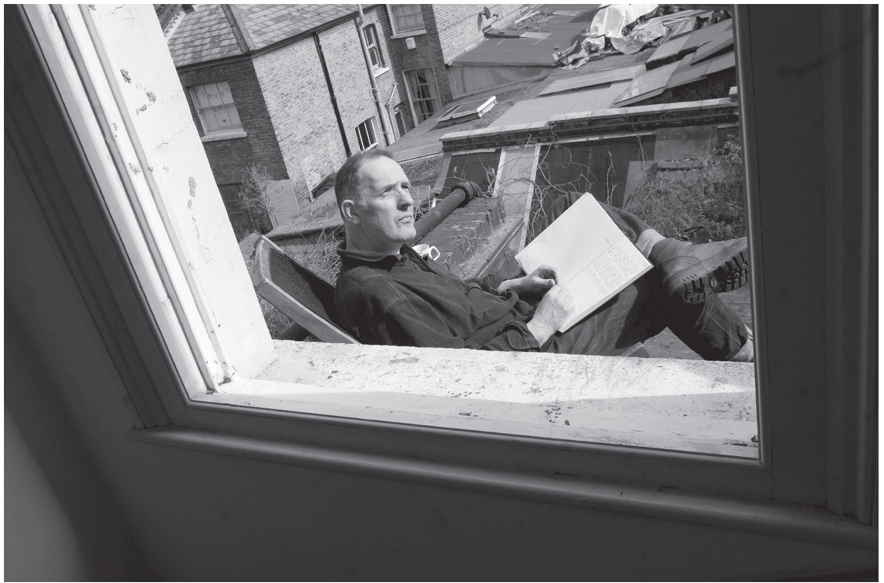

I’m building my airship in the Student Union; a month to go before the autumn term and the hall is empty. It’s early and brilliant sunlight pours down from the cinquefoil windows above me, flooding the low stage where I work.

I enjoy being here out of hours. I have the run of the building from as early until as late as I like.

Most of the student art and canvases have been stored over the summer – to be hung up again once the bar reopens – so the white walls are bare except for one large red and yellow canvas which looms to my left as I look down the room: MAKE SOUP.*

I like MAKE SOUP. It greets me every morning with bright clarity and purpose. The framed text beneath it reads:

NOTICE

Take a map of the British Isles. Draw a straight line diagonally across the map so that it cuts through Belfast and Nottingham. If your home is on this line, contact soupline@penkilnburn.com Arrangements will be made for Bill Drummond to visit and make one vat of soup for you, your family, and your close friends.

I appreciate the simplicity and generosity behind this venture. I like soup, for one, but also I like the sense of quest, the bold colours, the aesthetic of the large stark letters − four and four, MAKE SOUP – the fact Bill will rock up and physically make you literal soup with his actual hands.

I look on Bill’s Penkiln Burn website and find that there are many more canvases of the same size and style − PREPARE TO DIE, SILENCE, DRAW A LINE, 40 BUNCHES OF DAFFODILS, STAY − each with an attendant story and aim.

I ponder what a BLOODY GREAT AIRSHIP canvas would look like; three words, one above the other. I sketch it in my notebook.

• • • • •

March 2009

Bill’s workshop is a grey unit with a roll-shutter front, solid and anonymous on a ring road industrial estate … outside Norwich.* As the shutter rises it reveals a stacked interior. I follow him into the space, stepping over piles of books and magazines, around walls of filing cabinets and heaped boxes into a clearing with a large canvas suspended upside down on a stretch of bare white wall −

Rather than the portentous figure I’d been expecting, Bill seems a quiet, thoughtful man – far more tolerant and humorous than I’d imagined. On the drive back into town I think over the disparity between the Bill with the reputation for dark shenanigans that I’d read about in preparation for this meeting and Bill the enthusiastic instigator of spontaneous choir The17 because it’s the latter who’s sat beside me now, imagining aloud waking up tomorrow to find all recorded music had disappeared.

• • • • •

Later that day − Norwich Arts Centre

A dark hall. Set up on a stage at one end is The17 canvas collected this morning. On the floor down the middle of the room runs a white line, bisecting the eighty or so chairs on which people are starting to sit, filing into the gloom from the light outside. Shuffling to a seat while their eyes adjust.

Between the seats and the stage is a table.

On the table sit a laptop and an Anglepoise lamp. The lamp is the only light in the room and the room − once a church − is large, with a high black vault and pillars that mark out the nave and frame the stage and table.

More chairs fill, more shuffling, low whispers.

Bill appears and walks to the front to a scattered applause and sits down to face the audience.

‘Hello,’ he says, ‘my name is Bill Drummond and you are The17.’

Thereafter the audience, myself included, are told the story of The17, how it grew from the sounds in Bill’s head as a child and his lifelong love of choral music; how Bill tried to fight the music, which welled while he drove his Land Rover, tried to ignore it, but how he found it swirled and coalesced with other ideas he was having about the way music in the twentieth century − recorded, manufactured, sold and now ubiquitous − had lost touch with time, place, event and performance … how he’d sought to write these feelings out in under a hundred words; how he got it down to ninety:

Bill sells us the idea of The17, seduces the room. He sits in his circle of lamplight before the red canvas and reads out ALL RECORDED MUSIC and his sonorous Scots tones reverberate around the building, then he moves to another score, IMAGINE, and begins to form us into a choir − no previous musical experience necessary − to create a new music. Year zero now.

I can’t tell you much of what happened next because it would spoil the inherent mystery and magic of The17 as a uniquely immersive happening, but it’s enough to say that the choir, led by Bill, made sounds that swelled and filled the space, more moving and beautiful than I had ever expected and when we filed out of the building, blinking in the light, we were all grinning and buoyant and wanted to do it again.

• • • • •

Later still that day − Rob’s front room*

There is only one chair in the room where we later convene to talk. Bill sits on it. I sit on the floor. At this angle he appears even taller than he is – which is very tall.

The room is full of Bill’s work. About ten framed posters lean or hang on the walls having migrated from the art school bar.*

As we entered we passed two large canvases, GET YOUR HAIR CUT and MAKE SOUP. Since I last saw them in the union bar I’ve read, watched and researched the Drummond canon, spoken to fans, friends and collaborators and come to appreciate the extent of Bill’s range … and it’s fair to say MAKE SOUP is not the work that defines him in the public consciousness. No. That’d be THE MONEY;* an event chronicled in a film titled The K Foundation Burn a Million Quid.

I begin by asking if being Bill Drummond is sometimes a hindrance to work like The17.

‘It is something that I think about. Not all the time but … and I’m not the only person this happens to, it happens to most people that have done certain things. It casts a long shadow. I can feel that stuff I’ve done in the past will cast a shadow over whatever I do from here on in and there are times when that can get to me and it has influenced, to an extent, the way that I work. I have evolved ways of working where my name might not be attached to something.

It just so happens that piece thing behind you there, 40 BUNCHES OF DAFFODILS, that very thing, I’ve been doing that for about nine years now − I did it last week in Southend − and it’s got nothing to do with me. I go out in the street, I’m just a man, I’ve got a box of daffodils and I hand them out. There is no explanation. I don’t go out there to explain what it’s about. I do it and some people say, “What’s this about? Is this some sort of promotional thing?” and I say, “No no, I just want to give out forty bunches of daffodils.”’

Do you like that anonymity?

‘Yes, I like that. When Penguin were going to be putting out a book of mine called Bad Wisdom, at that point I wanted to call myself “W.E. Drummond” in that tradition of writers having two initials and their surname − which goes back to a time when most businesses were like that, WH Smith or whatever − but Penguin weren’t having it.

Whereas, when I first started doing The17, the first place we did it in the UK was in Newcastle. I’d posters designed just saying “The17 − a choir, blah blah” and I thought, “Wow, this looks so good! Who wouldn’t want to come along to something called ‘The17’!?” Of course, tickets weren’t really selling and the guy said, “Look, Bill, we’re going to have to stick your name on this,” and I really didn’t want it to be but I realised that I had to. I do realise with The17, when I do it publicly here, I have to attach my name to it just to make it work. I still balance doing that with going into all sorts of places and doing The17 where they don’t know who I am. It doesn’t matter.’

Months later, when I mention this to Stanley Donwood, he laughs:

‘This is why I love Bill Drummond’s work; it’s a constant series of genuinely inspired and brilliant ideas that somehow always seem to go awry or sideways; a constant cycle of admitting he doesn’t know what he’s doing and is probably naive or an idiot; but so fired with it. I find that inspiring. You know, who wouldn’t want to go along to something called “The17” with a great red painted sign? I would.’

Do you think your media caricature as a money-burning pop star has hindered the message and impact of subsequent work?

‘I know what you’re saying. I don’t know. I think I live a pretty unsociable life so I don’t get into situations much where these conversations can happen. I’m usually so focused or wrapped up in what I’m doing at that moment … Even when I’m being interviewed by a journalist, they don’t seem to ask those questions or maybe they tip-toe around them but then, when they write up their piece … it’s there. Maybe the first third of the feature will be a potted history of Bill Drummond. They feel that, if they don’t put all that in, whoever is reading the piece won’t know who this person they’re writing about is and I don’t know if that’s because I’ve never particularly gone out to have a large profile as a personality, maybe they’ve got to give that history to say, “Look, this person has been working for quite a long time in some sort of way and there’s some sort of thread here that leads through to where he’s at now …” I don’t know.’

You’ve always pursued that thread with a strong work ethic; is that linked to your Scottishness?

‘It is that, it’s very much that; that’s the background I come from, that’s the attitude. I’ve never been drawn to decadence. I’ve never been drawn to that thing of “the wild artist”, it just doesn’t interest me. The work ethic is … it’s not work for work’s sake. I get wrapped up. I get driven. The big motivation is that “life is short”. I’ve got a lot of things I want to get done. I could die tonight, that’s always there; and I’m always excited by what I’m doing. Exploration. The next thing.’

Do you see a pattern or progression in your work?

‘Usually, I can look back on what I’ve done − or look into myself − and see a theme. It’s almost always like I’m gnawing at the same bone or scratching the same wound. The17 this afternoon and “Doctorin’ the Tardis” − in one sense they’re a million miles apart, in another sense they come from a very similar place.’*

• • • • •

You often relate your ideas and journeys in a very characteristic first-person style when you write – often in retrospect, often in the form of a diary or log.

‘Yes, although some of the time I cheat. Sometimes I write in the present tense although it’s been written after the event and I’m aware, in the sense that all writing is lying, that I’m telling a story so I’m leaving out a percentage of things in order to tie a thing together so that it has a beginning, a middle and an end, and I will do that unconsciously. I don’t set out to do it but somehow I’ve learnt to do that. Sometimes I look back and think, “I’ve just learnt these tricks,” and sometimes I try to break free of that − I can see my own clichés.

I’d like to think I could write a proper book with one whole story, like a novelist does but I guess, for a successful novel and definitely a successful film, you have to have something that happens in the first ten minutes or the first X amount of pages in a novel that sets something up: Something has now happened that changes everything – you’ve got to get to the end for it to resolve itself, that’s what takes you through. That doesn’t really happen with my things.

You mentioned earlier that your writing is episodic, Dan. That’s what my stuff is and that’s what will stop it from ever crossing over commercially, I think. That’s the reason people can maybe get so far with one of my books and then go, “Okay, I get the picture,” you know? There’s no plot, it’s not going to go anywhere particularly.

‘When I was eighteen I read On the Road by Jack Kerouac − huge influence on me; that and Henry Miller is what got me wanting to write.

When they brought out the scroll of On the Road a couple of years ago I reread that and it was weird. I’m now, you know, quite a bit older than Jack Kerouac was when he died − he was young when he wrote it − and it’s only now that I realise “but there’s no story here, there’s nothing!” He could have cut that book off at any point, it has no conclusion.’

Has that influenced the way you see your role as a raconteur?

‘It was never a conscious thing; it wasn’t until me and Z, Mark Manning and I, went to New York to do Bad Wisdom* and we became like a double act, reading and telling the story, that I started learning how to actually talk to an audience. I knew I didn’t want to do it with a microphone. I knew I wanted to keep it as intimate as possible but I was aware that a craft was being learnt − it was an act to a certain extent but I knew that it also had to be for real. I know that, every time I go out and tell a story, like with The17 this afternoon, which I’ve told who knows how many times, I’ve got to somehow reach down into myself and make it real, in the same way as an actor has. Now, the last thing I ever wanted to be was an actor, but I know that’s what I’ve got to do and that has now become a big part, to use a cliché, of my practice as an artist; to get out there and tell stories and make it work, draw people in.