Полная версия

The Barefoot Emperor: An Ethiopian Tragedy

12

After His Holiness Cyril IV left Gondar in 1857, Tewodros marched to Delanta. He defeated a rebel governor there, then crossed the Abbai into Gojjam, where a force had risen against him. He captured the wife of one of their leaders and stripped her naked before having her shot. The rebels themselves he released; some were later captured again, and this time had to be executed. In Gojjam he found a slave market and ordered all the slaves to be freed, and many of them married each other. Then he moved north and did battle with the Agew and captured their leaders. The governor of Wegera rebelled and Tewodros moved his forces west to fight him, but the governor escaped. Tewodros had his prisoners’ hands and feet cut off, and hanged them from an acacia in Gorgora. He then marched to Zur Amba, and to Gondar, then back to Wegera and down to Zur Amba again.

That year, the year of St Mark, turned out like the others. Tewodros drove his men back and forth through the high plains, putting down rebellions. ‘He is coming – he is coming!’ hissed all before him, but the rebellions flared up again as soon as he had left. In three years of rule, nothing he had done had yet become solid: not the defeat of the Oromo, nor the appointments he made from among his own people, nor the alliances with Abune Selama, the Egyptians, or the scheming Europeans. His kingdom was little more than the province where his army was camped, his palace his campaigning tent, his power the last battle he had won. Only his strange record of success bound his territory together, and hope – less the hope in his new reforms than in old notions of peace through power, unity of Church and crown and common cause beneath the tattered Solomonic banner.

Between Wollo and Begemder there stood a mountain. Its dark cliffs were like the sides of a great ship, its flat summits decks on which cattle grazed and crops grew. No man could approach that mountain without being seen; it could be defended with the tiniest force. It was called Meqdela. In time Tewodros saw it as the still point of his turbulent world: ‘Meqdela shall be the storehouse of my treasures; those who love me will come and settle there.’

Only Tewodros would have favoured such a location, surrounded by his enemies. ‘Believing I had power,’ he wrote years later, ‘I brought all the Christians to the land of the heathen.’

Meqdela became garrison, treasury, prison, stronghold and home. Over the years, everything that was most valuable to him ended up on Meqdela – his captured cannon, his precious stones, his looted manuscripts, his most important and belligerent prisoners. Biru Goshu was chained there, also the ‘rightful’ Solomonic ruler Yohannis the Fool, who was always treated with deference by Tewodros. HH Cyril IV and Abune Selama had attended the dedication of the mountain as a place for Tewodros’s treasures, at which there was ‘extraordinary rejoicing’. He erected a church dedicated to his favourite sacred figure – Medhane Alem, ‘saviour of the world’.

Up there too he had sent Tewabach, his beloved wife. He visited Meqdela when he could, and those around him noticed the calm that settled upon him when he was with her. She was one of his ‘guardian angels’, it was said (the other one being John Bell). She prepared his food, read the Bible with him, and though no heir had yet been given them, God would choose the moment in His own time.

That year, 1858, in the early days of keremt, the season of big rains, Tewodros rode up the mountain and was with Tewabach. She washed the dust of battle from his feet. He was still for a moment and went nowhere and sat reading the Psalms – Lord, how are they increased that trouble me! Many are they that have risen against me … Each day the clouds gathered over the peaks, and after the storm, the sun shone on the plains far below and its web of silvery streams.

While he was on Meqdela, Tewabach fell ill. With each day, the emperor’s anxiety grew. He ate only shurro, fasting food. He spent the nights in Medhane Alem church praying for her. He begged the small group of Protestant missionaries to apply their medicine to her. His army, so used to movement, began to plunder the villages around Meqdela, and Tewodros was forced to drag himself from his wife’s bedside and lead his troops southwards where they were able to attack the Oromo. There they could plunder all they liked.

On the evening of 13 Nehase, the day of Rob, in the year 7350 since the creation of the world, Itege Tewabach died. Tewodros was still with his forces. He returned at once and had her body put in a coffin, and the coffin put on a stretcher. From his fortress at Meqdela, Tewodros took her embalmed body from camp to camp. She lay in her own tent and Tewodros spent hours sitting alone with her. She was taken to another mountain, Amba Gishen, whose flat-topped summit faced the heavens in the shape of a cross. While her funeral was being arranged, Tewodros composed a lament:

I pray, ask her before she goes

If Itege Tewabach was wife and servant

She of such wisdom, such industry, died yesterday

She served me and treated me by ploughing the earth.

Many miles away, deep in Oromo country, was another mourner. Banished to his native province of Yejju, Ras Ali wrote a bitter verse for the double loss of his daughter. He had not seen her since Tewodros had robbed him of his power and driven him into exile:

When I said to her ‘I love mead!’ she brought me honey.

When I said to her ‘I am hungry!’ she brought me my chosen fruits.

When I said to her ‘I am cold!’ she sent me shammas.

Taken by my thief, she is now carried on a coffin;

I grieve not, as long ago she disowned me.

Some weeks before her burial a comet appeared in the heavens. Each night Tewodros went out and sat in the stillness of the mountain to watch the arc streak across the sky. On the fortieth night it was gone. He marched his forces to the Oromo region of Wollo and massacred many people. He captured thousands of animals, and meat became cheaper than cabbage. He appointed a new governor, a loyal man, and went south and killed all those Oromo he could find between Gimbia and Geneta. The children he distributed among his nobles.

In Shoa, someone whispered of the governor’s secret dealings with a rebel. Tewodros had the governor chained and another appointed. That one revealed his treachery before Tewodros left Shoa. He had him chained too. Then he heard that the new governor of Wollo had rebelled. He rode north again, tens of thousands behind him. He rode in silence.

13

Walter Plowden now cut a sorry figure. He had few supporters left in the highlands. He had nothing to offer Tewodros. London had lost interest in his mission. He was desperate to reach the coast, to return to Britain, but the road was still blocked by Niguse. Plowden never doubted that Tewodros would move against Niguse, take Massawa from the Turks and gain access to the sea. But in four years he had been oddly slow to do so.

He was with the emperor on another campaign in Oromo country. ‘Leave the Oromo,’ he urged. ‘Move on Niguse in the north.’

Tewodros resented the interference, but reassured the consul: ‘Nothing but my death shall prevent me from placing you at Massawa.’

It was the last time the two men ever saw each other. They had met in 1855 in a flurry of mutual hope – the newly-crowned Tewodros with his attendant military angel; Plowden and his epistolary link to the powerhouse of the British Foreign Office. Tewodros’s reforms had been stalled by his hydra-headed enemies. Plowden’s paper link had proved just that. In recent years they had grown apart.

In the 1840s, when Plowden had first stumbled into the Ethiopian highlands, the world was a bigger place. British interests were less compromised. Palmerston in 1847 had been able to share Plowden’s enthusiasm for an entire new territory, an ancient half-forgotten kingdom. Trade and thwarting the French added a little pragmatic purpose to Plowden’s carefree project.

By the time of Tewodros’s coronation in 1855, the Foreign Secretary Lord Clarendon remained thrilled by Plowden’s assessment of the emergence of Tewodros and the prospect of opening up relations: ‘Have read his very able report with great interest, and entirely approve his language and proceedings.’

But in the following years it had been impossible for Plowden even to leave the country. In the meantime the convergence of interests in the Red Sea – French, British, Egyptian and Ottoman – had made foreign policy a much more delicate exercise. Involvement in overseas territories was also seen as having a much greater price: the Indian Mutiny had revealed the strange truth that native peoples did not always appreciate the presence of the British. Ethiopia and Tewodros were an equation that didn’t work out; they were risk without profit.

To the Foreign Office, Consul Plowden slipped from view. There was no more talk of receiving an ambassador. By 1860 Lord Russell, Clarendon’s successor as Foreign Secretary, was fed up with this emperor and his endless struggles; all that mattered was the coast. Plowden was wasting his time in the highlands: ‘You will therefore return to Massawa, which is your proper residence, and you will not leave it, unless under very exceptional circumstances.’

But he could not even reach Massawa.

The only duty the Foreign Office now asked of Plowden was to tell Tewodros to stop his persecution of a group of Ethiopian Catholics. Very reluctantly, Plowden sent their letter on to Tewodros: ‘We would advise you earnestly to be like ourselves, that all people shall have religious liberty in your country.’

Not for the first time, Tewodros was baffled by the Europeans. What was his old friend Plowden doing, speaking up for his enemies? The French were supporting Niguse in the north, and Niguse had promised to convert to Rome when he had defeated Tewodros. Yet through Plowden, Tewodros was being asked to accept the Catholics. Was Plowden in league with the French?

Tewodros read the letter on campaign. He handed it to an aide. Six hours later he gave the order to break camp. He never replied.

Seventeen years had passed since Plowden first arrived in the country. ‘The love of change and of the wildest freedom first led me to Abyssinia and made me feel as imprisonment the least restraint.’ Now in Gondar, in and out of fever, lying on another alga in another season of highland rains, he recalled those early days – the excitement of Biru’s camp with just a thaler to his name, the week of ‘song and merrymaking’ after killing an elephant, then rushing to war; hunting hippo on the shores of Lake Tana, or the sunset scene, ‘so strange and novel’, of watching thousands of Oromo swimming the Blue Nile in its mile-deep gorge.

There was the time spent in a mini-fortress with the eighteen-stone Oromo chief Ahmed Huru – ‘the rain prevented us from going out, so we drank tej without ceasing’, and without eating, for six days, while Ahmed ‘eyed me askance in a most ludicrous way’. (He also made an offer to Plowden of his daughter ‘to be my lawful wife, and of a fat portion of his dominions’.)

Plowden had always had luck – leaving his residence in Monculu just hours before the arrival of an army that burned the village to the ground. He had won over the right people – Biru and Wube and Abune Selama and the dangerous Haile the Devil – ‘with my usual good fortune in Abyssinia, I made him my friend’. His friendship with Tewodros was, in its best moments, of great significance to them both. Once on parting for the battlefield the emperor had taken Plowden by the hand and said: ‘All men are mortal; if anything happens to me, befriend my son. Write to your country; say you had a friend who loved you all, and who intended to send an embassy to you for your friendship, and beg them to support my son.’ When Plowden agreed, Tewodros told him: ‘I love and trust you – goodbye!’

Plowden heard the echoes of English history in the country’s arcane customs and codes and its battle lore. He saw Ethiopia on the road of progress, behind Europe, but on the same road, in its own Middle Ages. He admired too the defiant strangeness, the beauty of the landscape, the sights that the people in it would suddenly produce, like gugs – ‘a fine animated game’ of feigned battle: ‘with their scarlet saddle-cloths and glittering benaicka flashing in the sun, and long sheepskins on their shoulders, the hair streaming as they gallop, they present a picturesque and wild appearance’.

From the time that he became consul and signed the treaty, something of Plowden’s initial joy was lost. Even the excitement of Tewodros’s early reign soured. Five years he had been stuck in the highlands. Now his luck seeped from him. In November 1859, playing a game of gugs himself, his horse rolled and he broke his leg. For two months he was ‘entirely incapacitated’. When he wrote again to Lord Russell, and apologised, it was to tell him that he had heard that the French had sent an embassy to Massawa – further backing for Niguse. For some time the rivalry between Niguse and Tewodros had reflected the growing rivalry for the Red Sea between Britain and France. Niguse had the advantage, having blocked Tewodros from the coast. Tewodros now appeared the loser.

In fact, he had already made his move. The very next day, Plowden received the news he had waited years for: from Shoa, Tewodros had suddenly marched his forces to Tigray. It was an astonishing feat. Only Tewodros could have achieved it. Six hundred miles through mountainous terrain in forty-odd days. With 60,000 men he had confronted Niguse. Niguse fled to the west. After five years, Tewodros had at last added Tigray to his realm. His territory now stretched from the Awash river in the south to the mountains above the Red Sea coast. It included Aksum, seat of the first Ethiopian empire. It revived for many the stalled hopes of Tewodros’s early years. Plowden was among them.

In Gondar, he hopped to his feet. He packed his belongings and prepared for the journey. He would see Tewodros in Tigray, then continue on to the coast. In Britain he could have his leg set properly and, with Tewodros’s new strategic advantage, present his case for the first time in person to the Foreign Office. Raised up onto a mule, he was escorted out of Gondar.

His small party was crossing the River Keha when a group of four hundred men attacked them. They were led by Gared, a nephew of Tewodros but a follower of Niguse. Plowden’s side was pierced by a spear. He died nine days later.

Later that year, Tewodros avenged the death of his old friend. He drew Gared into battle at Debarek. It was Yohannis, John Bell – in the uniform of the liqemekwas – who spotted Gared and shot him dead. But as he fired his pistol, Gared’s brother killed Bell, and was himself killed by Tewodros.

Tewodros knelt beside the body of John Bell. First Tewabach, then Plowden, and now Bell.

‘Yohannis! Poor Yohannis,’ he wept. ‘You saved my life, but at the expense of your own.’

Witnesses saw him sit there for some moments, overcome by grief. Suddenly he rose. He leapt onto the fallen figure of Bell’s killer, thrusting his spear again and again into the corpse’s head. ‘You wretch, you have taken from me my best friend, my only friend!’

Some months later, a visiting missionary showed the emperor a ‘stereoscopic image’. It showed a soldier weeping at the grave of friends fallen in recent fighting at Melegnano. When Tewodros saw the picture, he gazed at it a long time.

‘Let me also weep,’ he told the missionary, ‘for I have lost my best friends.’

III

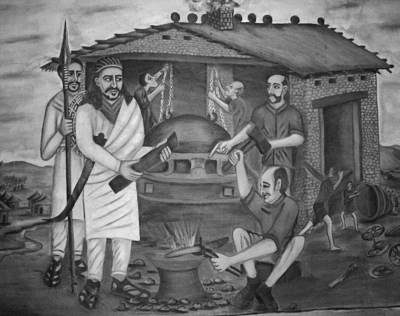

Tewodros at the Gefat foundry, from a mural in the bar of the Hotel Tewodros, Debre Tabor

14

One of the first letters Tewodros sent after his coronation in 1855 was to Samuel Gobat, Anglican bishop of Jerusalem. Gobat had been a missionary in Ethiopia some twenty years earlier, but had been forced out by the country’s paralysing instability. Like others, he had watched the emergence of Tewodros and felt the chance had come again – not for him, but for a new generation of evangelical workers.

Tewodros, however, was asking him for artisans and craftsmen. He certainly did not want priests. ‘You know the situation of our country. It is where you lived. It has been divided, one against another, even into three. Now, by the power of God, I have unified it, so now let not priests who disrupt the faith come to me … of workers, let one who ploughs with a fire-wheel come, bringing the engine with him to me. I have heard people say that it exists.’

Eight months later, Samuel Gobat stood before the Anglican congregation on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. Seven fresh-faced, Swiss-trained missionaries gazed up at him.

‘Beloved brethren,’ he began, ‘the hour has come for which you have for some years been preparing yourselves, the hour for parting with the Christians in whose circle your spiritual life has been developed.’

The bishop was a solid and portly man. A great bib of a white beard hung down his chest. In his address, he drew on his own experience in the field years earlier.

‘Now, you will have to lean on the Lord in your weakness, in a land that is covered with darkness, and among a people who are still in the shadow of death. If you have ever felt and understood your infinite weakness and helplessness, as every one must into whose soul a ray from the Sun of Righteousness has penetrated, you must increasingly feel it in this solemn hour, as you see before you the difficulties of the journey and the deep degradation of the people to whom you are going …’

But with their own deviant version of Christianity, the Ethiopians were a people not entirely without redemption.

‘According to the ideas of the present king, who himself reads the Bible in his own language, and according to the practice of the Abune Selama, I do not think you will have any obstacle in spreading the Word of God. Judging by my own experience, I believe that many an Abyssinian will receive the Bible with thankfulness.’

He did warn them of the ambiguity that lay behind their mission.

‘Do not put to the king direct questions, so as to get decisive answers, as to whether you may settle in his country as messengers of salvation. The better plan will be not to bring the matter forward, nor seem anxious about it, but try first to persuade and convince the king through your behaviour, that you are true Christians who are led by the Spirit and the Word of God.’

Gobat believed that in Africa a great new world of evangelism was opening up. He and his committee planned an ‘Apostelstrasse’, a series of twelve stations between Egypt and Ethiopia which would help supply the Ethiopian mission, as well as radiating the Word of God from each station.

‘The field that lies desert before you, and must be worked and turned into a garden of God, is a wide, almost immeasurable field. It not only includes all Abyssinia, but the neighbouring heathenish Galla tribes, and the whole centre of Africa, of which Abyssinia is only the entrance. There the devil has his kingdom, and for thousands of years it has been allowed to go on quietly and undisturbed beneath his government.’

He concluded by reminding them that they were invited as artisans, and that their missionary activity should be covert.

‘You may feel it strange and disagreeable to hear that instead of preaching and baptising you are asked to work with your hands, and partly to earn your own living. The devil will whisper to you, and your own hearts will answer him loudly enough: “Work and earn our bread, live and die, we could have done in Germany, without the long preparation, and without going to wild Abyssinia.”’

Three of the men were so alarmed by Gobat’s portrait of wild Abyssinia that they pulled out. Among the others there were reservations. Only two out of the seven – Mayer and Kienzlen – set off for Ethiopia with anything approaching enthusiasm.

15

For a few years the mission ran smoothly. Tewodros was too busy campaigning to pay the missionaries much attention. But in 1858 he asked them to treat the dying Tewabach, and though they could do nothing, it marked the beginning of a closer relationship. As his own clergy revealed themselves to him as hidebound fools, so Tewodros took to spending time with the south German Pietists, and developed a respect for their brand of unadorned faith. They in turn overlooked his brutal sorties against the Oromo, and came to admire him.

‘He is,’ wrote Kienzlen, ‘the only man in Abyssinia who possesses the fear of God.’

In 1859, a new missionary arrived – Theophilus Waldmeier, a young Swiss of deep humility and an almost saintly gentleness. Tewodros always had favourites among the foreigners, and as the years passed Waldmeier came to fill the gap left by John Bell.

Theophilus Waldmeier had had a strict Catholic upbringing. As a boy he soon realised that ‘the priest is a bigger sinner than other people’. His grandmother beat him with a stick for saying so and he ran away from home. He rejected Catholicism and ended up at missionary school, at the famous St Chrischona College. There Samuel Gobat came and selected him for service in Ethiopia.

He travelled to Ethiopia with another recruit, Saalmuller. With them too was the German missionary Martin Flad and his new wife, Sister Paulina. As a concession to Tewodros’s secular ambitions, they were also accompanied by a man named Schroth and his son. They were gunsmiths. In the last days of 1858 the party set out across the Egyptian desert. A long line of camels stretched behind them – thirty-two, loaded ‘mostly with Amharic Bibles and Testaments’.

The journey itself was a great excitement for young Waldmeier. He was interested in seeing Egypt because it was the land of the pharaohs and the children of Israel had lived there in exile. The desert looked like ‘a past world burned by the wrath of God’, and desert travelling was hard, he warned in his own innocent way, because ‘water is scarce’.

It became harder, and hotter. The sperm-candles in their baggage oozed through the crates and onto the flanks of the camels. Everyone but Mrs Flad fell ill, and they camped for days slumped in the heat, in the shadow of mounds of Bibles. When Schroth and his son died, the others could barely drag themselves out to scrape at the sand to bury them. They all believed that they would soon go the same way. But the Lord spared them, and soon they found themselves climbing into the highlands, surrounded by wild roses and fresh water.

At that time, in 1859, John Bell was liqemekwas, and greeted them in the royal camp. He in turn presented them to Tewodros. Waldmeier thought the emperor very civil. With great charm he asked about their journey, and expressed regret that Schroth and his son had died on the road.

‘It is on account of my sins,’ Tewodros told the missionaries, ‘that God took these two men away from me.’

Tewodros sent them to Meqdela. It was for their own safety. Theophilus Waldmeier settled easily into his new mountaintop home. He shared a hut with five of the other missionaries, studied Amharic and taught some basic mechanical skills. There were long debates about the Bible with the royal scribe Debtera Zeneb, who in time came to see the true light of the Gospel.

Waldmeier was delighted by the country of his calling. After the rains, he wrote, the entire land turned into ‘a beautiful flower garden’. The people were ‘nice-looking’ and ‘clever in everything when taught’. Like Plowden before him, he dreamed of Ethiopia’s development, of its prospects if it could ‘only have good government, and its own old sea-port of Massowah’. He believed too in Tewodros’s good intentions. ‘Where is another king to be found, who in spite of his power and greatness in self-denial disdains all comforts, luxury and good living – he lives very poorly, while he rewards and gives royally – who in living trust in God’s help lays before his feet heathen and wild nations?’