Полная версия

The Barefoot Emperor: An Ethiopian Tragedy

THE BAREFOOT EMPEROR

An Ethiopian Tragedy

PHILIP MARSDEN

To Clio

CONTENTS

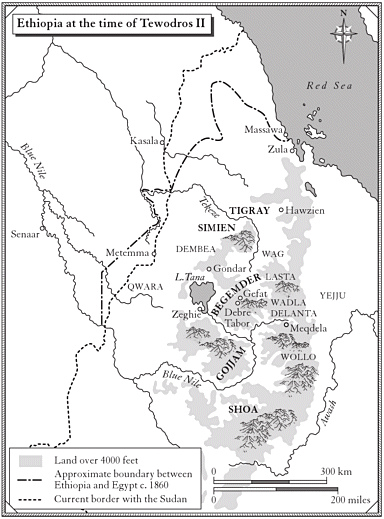

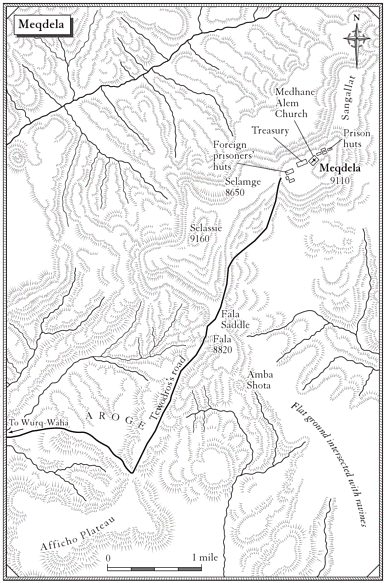

Maps: Ethiopia at the time of Tewodros II Meqdela Author’s Note Glossary Prologue THE BAREFOOT EMPEROR Notes Bibliography

AUTHOR’S NOTE

For the purposes of the story, the names ‘Ethiopia’ and ‘Abyssinia’ can be seen as interchangeable. I have used Ethiopia in the text, but have not changed Abyssinia where it appears in quoted material. A degree of revisionist spelling has been necessary to rid Ethiopian places and people of their Eurocentric tarnish – thus Magdala becomes Meqdela, Theodore, Tewodros (pronounced with a silent ‘w’– Te-odros).

Over the years, many hundreds of people have contributed to my own understanding of Ethiopia, its people and its past – monks and farmers, scholars and patriots, politicians and painters, all too numerous to mention. But for the Tewodros story particular thanks are due to: Professor Richard Pankhurst, for his encouragement, for digging out references and notes; the historian Shiferaw Bekele of Addis Ababa University, for his time and his clear-sighted view of Tewodros and his legacy; Dr Mandefro Belayneh for his enthusiasm; Hiluf Berhe, as always a tireless walker and perfect companion, for his help in Bahir Dar, Debre Tabor, Meqdela, and for translating the Chronicles of Zeneb; Kidame of the town of Kon, who came with us to Meqdela with his donkeys, for his fighting off of the hyenas that night in the valley of Wurq-Waha; Tony Hickey, for equipment; Sandy Holt-Wilson, an eye surgeon who has gathered together an archive of Tewodros’s son, Alemayehu Tewodros, and lectures about him to raise money for an eye unit at Gondar University (www. Gondar Eye Site. com); Jean Southon, great-niece of Captain Speedy, who allowed me to see family papers; Colonel Damtew Kassa and his cousins, direct descendants of Tewodros; HE Bob Dewar, British Ambassador to Ethiopia; the Scholarship Committee of the Harold Hyam Wingate Foundation; Susi Rech for translation of the German of Flad and Waldmeier; Will Hobson for his multilingual skills; Roland Chambers for help with Ransome references; Dr Iain Robertson Smith, Colin Thubron, Gillon Aitken, Mike Fishwick, Richard Johnson and Robert Lacey for their support; and Charlotte, whose judgements have greatly improved what follows and whose tireless enthusiasm made producing it so enjoyable.

GLOSSARY

abet – a greeting call, used to attract attention, or to acknowledge such a call

abun, abune – the head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, at this time always a Copt

adarash – meeting hall

afe-negus – literally ‘mouth of the king’, royal spokesman

aleqa – chief or head

alga – bed, wooden-framed and sprung with a lattice of leather straps; also means throne

amba – a flat-topped mountain peak, often surrounded by cliffs, a natural fortress or isolated site for a monastic community

ato – Mister

Ayzore! – ‘Be strong!’ Comradely call of encouragement in battle, travel or labour

azmari – minstrel, composer and singer of witty verses, accompanied by masenqo, single-stringed fiddle

balderada – a chaperon and translator appointed to assist foreign visitors at the Ethiopian court

basha – from the Turkish ‘pasha’, used for high officials, and with irony in the case of Captain Speedy (‘Basha Felika’)

belg – the ‘small’ rains, usually occurring between late January and early March

bitwedded – ‘favourite’, court title, used often as qualifier to other titles like ras

debtera – a non-ordained rank of the Ethiopian Church, responsible for singing and dancing, and often possessed of peripheral religious powers, as herbalist and spell-maker

dejazmach – literally ‘commander of the gate’, a military and noble rank just below ras

doomfata –the recital of heroic deeds

falasha –an Ethiopian Jew

farenj –foreigner (adjectival form – farenji)

Fekkare Iyesus –The Interpretation of Jesus, Ethiopian sacred text

Fetha Negest – ‘laws of the kings’, the book of Ethiopian law

fitawrari – ‘commander of the front’or ‘vanguard’

Galla –former name of the Oromo people, originally pastoralists from the southern and eastern highlands

giraf –hippo-hide whip

godjo –stone-built hut typical of Tigray and the north of Ethiopia

grazmach –literally ‘leader of the left’, military and noble rank below dejazmach

gugs –a game of mock combat, involving two teams of horsemen charging each other: beautiful to watch, hazardous to play

Habesh –the name Ethiopians often use for themselves, from the Arabic ‘mixed’, and the basis of the name ‘Abyssinia’

hakim –doctor

hudaddie –Lenten fast, fifty-six days long

ichege –head monk of Ethiopia, and being native often more powerful than the Coptic abun

ika-bet – ‘thing house’, repository of church treasures

injera – flat bread

isshi – ubiquitous Amharic expression, meaning OK/of course/ very well

itege – empress or queen

Jan Hoi –Your Majesty

kebbero – large church drum

Kebre Negest – ‘the glory of the kings’, Ethiopia’s mythical charter dating to about the thirteenth century, drawing together many myths including the story of Solomon, Sheba and Menelik their son, and the Ethiopian inheritance of Mosaic law and the Ark of the Covenant

kegnazmach – literally ‘leader of the right’, military and noble rank below dejazmach

kentiba – mayor

kiddus – saint or holy man

kinkob – ceremonial robe

koso – a purgative against intestinal worms, used regularly by Ethiopian highlanders

lemd – cape or tunic

lij – ‘son’ or ‘child’, used as title for young noble males

liqemekwas – high court official

margaf – cotton scarf or small shawl

mekdes – the sanctuary of a church, the section in which is housed the tabot

mesob – free-standing flat-topped basket, on which is spread injera

naib – a Turkish name for the local rulers of the coastal region around Massawa

negarit – war drum, used to call men to arms, as well as acting as a symbol of authority

negus – king

shamma – large cotton shawl

shifta – bandit

shum – regional ruler, military chief

tabot – the sacred object at the heart of each Ethiopian church, never seen by laymen, representing both the Ark of the Covenant and the church’s given saint

tankwa – boat of lashed-together papyrus, used on Lake Tana

teff – indigenous Ethiopian wheat used to make injera

tej – mead

tella bet – beer house

thaler – the Maria Theresa thaler, common currency of the highlands, minted without alloy, and equivalent to about six shillings at this time

Tigrigna – the language of Tigray, northern Ethiopia, derived as Amharic from Ge’ez and the Semitic family of languages

timtim – white turban worn by priests

wat – sauce

weyzero – Mrs

PROLOGUE

I

‘Yetewodros menged.’ The monk’s finger pushed out from the folds of his shawl, far out into the morning, to a shadowy line on the opposite slope. ‘Tewodros’s road.’

After the easy undulations of the plateau, the main road here drops to a place they call the ‘natural bridge’. It’s one of those sudden sights in the Ethiopian highlands that pull you up short, as if the earth’s skin has been ripped aside to expose the skeletal frame of chasms beneath. At the natural bridge itself, beyond the clifftop monastery, the road runs the length of a ridge of rock so narrow that on each side you look down to a shingle bed some 3,000 feet below. To the north is the Tekeze basin, to the south the Abbai, the Blue Nile. The two rivers do not merge until seven hundred miles to the north-west, in the yellowy heat of the Sahara desert.

After the bridge is a new cutting. Within the last few years, as part of the government’s ambitious transport programme, it has been bulldozed and blasted through the hill. To one side, forgotten and unused, is an old grassy track – Tewodros’s road.

In Addis Ababa, no one could tell me what remained of the road. No account exists of it later than its building. I asked scholars at the university, and they were vague – those who had reached Tewodros’s mountaintop fortress of Meqdela had walked in from the south-east. At Bahir Dar University too they knew nothing, nor did a local historian at the school in the emperor’s old capital of Debre Tabor – a school named Tewodros II Secondary School, with the emperor’s spear-carrying image daubed on its classroom wall.

I stepped onto the old road. My boots crunched in its basalt dust. It wasn’t much to look at – a little wider than the mule paths and market routes that criss-cross the highlands. Sumach bushes dotted its course. The inner edge was sliced back well into the rock. A century and a half of rains had rounded its outer edges, washing loose soil and stones down gullies that plunged far into the gorge below.

Yet of all the moments of his extraordinary reign, Tewodros’s building of this road stands out as the most heroic and the most tragic. In October 1867, he burnt his capital at Debre Tabor and with 50,000 people left for the mountain at Meqdela. Week after week, led by the emperor himself, his half-starved army hacked at the ground with their spears, with mattocks, with their bare hands. They felled trees, banked up slopes, rubble-filled streams and smoothed off the rocks with soil. It was a journey of about 150 miles; a good messenger could do it in a few days. It would take Tewodros six months.

Little remained to him at that point, no territory and no support beyond his slow-moving camp. Untouchable on high cliffs, and from the shadows of thick forest, rebels followed his progress. They picked off water-carriers, the sick and the slow, the stragglers. They didn’t dare mount an attack. In part, Tewodros was protected by the strange air of invincibility that had surrounded him throughout his reign. But with him, on wooden wagons, was something more solid – dozens of pieces of artillery, and one in particular, the largest of all, cast in his own foundry a few months earlier, a seven-ton monster he had named Sevastopol. He was building the road for his guns.

Tewodros had another enemy. Years earlier he had chained up the British consul and the man was still in chains, with a number of other Europeans, high on the flat summit of Meqdela. Diplomacy had run its course. Now the British, irritated and affronted, had landed their forces on the Red Sea coast to try to release the hostages. Every week a few thousand more arrived. They were building a port in the desert, landing supplies in vast quantities. They were installing condensers to provide water, building a railway to the mountains. Soon they would be ready to march to Meqdela. All his life, the emperor had dreamed of bringing European technology to his people. Now it was coming.

So Tewodros was hurrying. He was desperate to reach Meqdela before the British, to line the clifftops with Sevastopol and his other big guns, to face the enemy. Hour by hour, his men flattened the ground so that the timber gun-carriages could creak forward over the rocks. If they managed two miles or more, it was a good day.

Here at the natural bridge, they paused for weeks in order to hack out the section across the broken ground, then up the slope towards Zebit. When it was ready, hundreds of men bent to the leather straps that fanned forward from the wagon of Sevastopol, and inch by inch hauled the gun up the slope. Many fell as they did so. From the cliffs the rebels hurled down rocks and spears.

Up on the high plateau again, the going was easier. Like some slow parade of votive statues, Sevastopol and the other guns slid across the plains towards Meqdela. Sometimes at day’s end, with the sun dropping over the short section of new road behind them, and as his men rested in the sudden chill of dusk, Tewodros would climb up and stretch his arms over Sevastopol’s great girth, as if its bulk might correct the fragility of his position. For years his followers had seen him as the incarnation of divine prophecy, a champion of their own Christian and Judaic inheritance. Now they gazed up at him on the gun-carriage and began to whisper of ‘yetewodros amlak’– ‘the idol of Tewodros’.

At Bet Hor, on the edge of the Jidda gorge, British forces reached Tewodros’s road shortly after he had passed. They were amazed. Travelling with them was the geographer Clements Markham, and he stood at the cliff-edge and conceded the determination of the enemy: ‘A most remarkable work –a monument of dogged and unconquerable resolution. Rocks were blasted, trees sawn down, revetment walls of loose stone mixed with earth and branches built up, and everywhere a strengthening hedge of branches at the outer sides, to prevent the earthwork from slipping.’

Later Markham gathered more information about how Tewodros had transported Sevastopol from Debre Tabor, and became convinced that the story ‘entitles his march to rank as one of the most remarkable in history’. Dr Blanc, at the time a prisoner on Meqdela, and no friend of Tewodros, echoed Markham’s words. It was, he wrote in his own account, ‘a march unequalled in the annals of history’.

From Bet Hor, the route to Meqdela drops several thousand feet to the Jidda gorge, up onto the Delanta plateau and down again to the Beshilo river. Tewodros’s road is still visible in places, chiselled into the side of cliffs, scored around the bulge of steep-sided bluffs, zigzagging up dusty slopes. It took him and his followers months to build this section. I walked it in a few days. At eleven o’clock one morning, five o’clock Ethiopian time,* I reached the Fala saddle and saw the peak of Meqdela ahead, half-hidden by scarves of cloud. As I crossed Selamge, the cloud blew away to reveal a shadowy row of cliffs. It was a grim sight. The mountain’s flat peak was edged on all sides by a sheer drop of black basalt.

At the northern end of the massif, below the peak of Selassie, the entire scene was spread out below. I looked back at the way I had come. In the haze was the far-off horizon of Delanta, the descent to the Beshilo, the snaking valley of Wurq-Waha – ‘golden water’– and the final ascent. When Tewodros began to haul Sevastopol across this section, the advance guard of the British were just twenty or thirty miles behind him.

A short way along the clifftop was a small settlement. Thatched huts stood beneath the silvery-leaved eucalyptus; stockades were ringed by pickets of giant euphorbia. A young boy was following a slow herd of cattle back towards the huts. To one side stood a crude canopy of corrugated iron. Lying beneath it, looking somewhat like a fallen bell, still lay the bronze mass of Sevastopol.

II

I first heard about Ethiopia and Tewodros at the same time. My grandmother had a companion known simply as ‘Pillio’, who had tutored my uncle and father as boys and, so the story went, was the daughter of an Ethiopian princess from the days of ‘mad King Theodore’. From that time on, her high-necked beauty, her mysterious silence and this mad King Theodore took up lodgings together in some quiet suburb of my mind.

Much later, in the early 1980s, I went to Ethiopia for the first time. One evening, after curfew, I read Alan Moorehead’s sketch of Tewodros and the Meqdela campaign in The Blue Nile: ‘It has always been accepted that the Emperor Theodore was a mad dog let loose, a sort of black reincarnation of Ivan the Terrible.’ Clements Markham likened him to Peter the Great. During the bloody days of the Derg regime, with its random killings and its merciless war in Tigray and Eritrea, I saw parallels much closer to hand – with Colonel Mengistu and his ‘Red Terror’.

When I next visited Ethiopia some fifteen years later, Mengistu had gone. The paralysing fear had disappeared, replaced by a lurching and chaotic openness. Self-expression was no longer a subversive act. The iconography of globalised culture had shunted aside Soviet agitprop. On T-shirts and posters were stencilled the images of Leonardo DiCaprio, Tupac Shakur, Madonna and David Beckham. Emperor Haile Selassie’s regal figure had reappeared both in its local form and in the much-travelled Rastafarian version. In internet cafés, the most commonly consulted website was for US immigration and the Green Card Lottery.

I was surprised to find Tewodros among all this. But he was everywhere – on the walls of bars and on locally-printed T-shirts. I watched a teenager idly chalk his image on a rock. Market stalls sold Tewodros badges and Tewodros cotton tunics. In a government office, I spotted his fierce glare above an anti-corruption slogan: ‘Governing Self Behaviour is Best Skill of All’. At political rallies, I was told, a mention of his name was guaranteed to win the crowd. Everyone had an opinion of him, from taxi-drivers to suited businessmen, and it was universally positive. ‘Tewodros was our greatest patriot, a hero.’

‘But he was a monster!’ I spluttered.

‘So much Tewodros loved his country – I’m sorry, only to think of him makes me cry.’

I went to see an old friend. Teshome and I had travelled together years earlier, in the dark days of Colonel Mengistu. Teshome had always been a convincing and witty sceptic – sceptical about Mengistu and his Soviet backers, sceptical about Emperor Haile Selassie before them. Several years at an American law school had only made his suspicion of all power more articulate. The current regime was just as bad. But when it came to Tewodros, the scepticism vanished. ‘Tewodros?’ He paused, steepling his fingers in a courtroom gesture of reasoned thought. ‘What you have to understand, Philip, is that without him there would be no modern Ethiopia. Period.’

At the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, I thumbed through the library’s card index. It was all there – the Tewodros dramas, the Tewodros novels, the poems and the doctoral theses. One or two voices spoke out against him, but the predominant tone was hagiographic. Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin, who wrote a play called Tewodros in 1962, said that the ‘heroification’ of the emperor was necessary in part because foreign authors had so tarnished his image. He in turn accused the critical Ethiopian scholars of ‘meqegna’, jealousy, or needless iconoclasm.

Somewhere between the cult of Tewodros and its bloodless deconstruction lay the story itself. Only by reading the accounts of contemporary witnesses do the raw impressions of the time emerge. The European hostages left between them a mass of memoirs and letters. The Ethiopian side is less well represented, but there are a good number of contemporary Amharic letters, including those from Tewodros himself. Several Amharic chronicles too survive. Scholars have dismissed these for their eccentric chronology and distortions, but like the letters their viewpoint and language (even in translation) are wonderfully evocative. With the European accounts they conjure up a remarkable moment in history.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the world was an archipelago of loosely connected peoples. All over Africa and Asia, a pushy Europe was coming face to face with long-isolated nations. It is a process that has, in little more than a century, accelerated into a global frenzy of connectivity – skies criss-crossed by vapour trails, overhead cables pulsing with hypertext. In few instances were the initial meetings so bright and hopeful, or so swiftly shadowed, as they were in the 1850s and 1860s in Ethiopia.

For the ancient empire, tracing its roots to the reign of King Solomon nearly 3,000 years earlier, the episode was a bracing and too-sudden encounter with the modern age. For the British, reaching the height of imperial power, what began as an irksome diversion required in the end one of the most bizarre and elaborate military campaigns ever undertaken.

Yet for all its historical interest, the story belongs to the individuals – the European envoys, the adventurers and missionaries drawn into Tewodros’s thrilling and perilous world; the Ethiopians who followed him with such passion; and the emperor himself with his messianic appeal, his capricious brutality.

Few images survive of Tewodros and many of those that do are fanciful. The one that is pinned to my wall as I write this comes from the frontispiece of Hormuzd Rassam’s two-volume Narrative of the British Mission to Theodore, King of Abyssinia (1869). Said to have been a fair likeness, the lithograph shows him on a high rock on the edge of the Blue Nile. He is dressed simply, in cotton shamma and loose cotton trousers. His feet are bare. Gripped in his right hand is a slender seven-foot spear; his left wrist rests on the stock of one of two pistols thrust into his belt. He is looking to one side, at a group of his followers struggling to follow him up the slope. In his stance and expression is a tense ambiguity, between impatience and concern, compassion and anger.

In Addis Ababa, just before I returned in 2003, the cult of Tewodros had found physical expression on one of the most prominent roundabouts in the city. Squatting on a high stony plinth, on the back of a vast wooden wagon, was a reproduction of Sevastopol. The installation had been encouraged by the country’s president, Girma Welde Giyorgis – a fan of Tewodros – and instigated by the mayor of Addis Ababa and Professor Richard Pankhurst. I’d known Richard for over twenty years, and when I went to see him and his wife Rita in their leafy villa, he told me the story in his own dry and ironic way. But he too recognised Tewodros’s stature.

‘We flew up in an old Soviet helicopter, landed on Meqdela. We were back in Addis by teatime.’ They took measurements of the gun where it lay. On the roundabout halfway down Churchill Avenue, looking at the dimensions and the traffic island, Richard began to have doubts. In Tewodros’s day, on its wagon, Sevastopol may have been an impressive sight, but now, on a busy interchange, dwarfed by Isuzu trucks and Toyota Land Cruisers, the seven-ton mortar would look tiny.