Полная версия

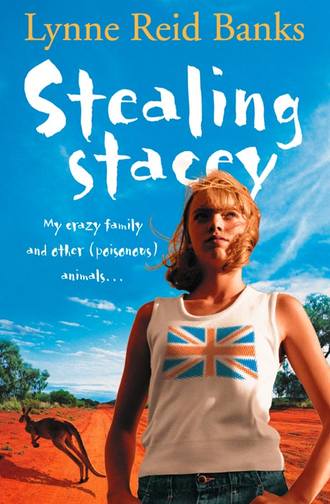

Stealing Stacey

Gran ate oysters till I lost count. I tried one. Yuck! It was like solid snot. She laughed when I said that. She was laughing a lot. Then, just as I was eating my third pudding, something went clunk in my head and I nearly fell asleep right into the whipped cream. Gran saw my eyes closing.

“You’re jet-lagged,” she said. “Come on, sweetness. Bed for you.”

In my room I dropped on to the big double bed. I felt Gran pulling my shoes off. That was all I knew. When I woke up it was dark. I lay awake looking out of the window at the stars. They were so big and clear! After a bit, I fell back to sleep. I felt so happy. England and school were just nowhere. As for Mum and Dad… I pushed them out of my mind. I didn’t want anything to get in the way of having a wonderful time.

Next day everything was a bit crazy. We had breakfast at lunch time, then went for a drive in a cab round the city to see the rich people’s big houses. Then we had a swim in the wonderful blue sea. The beach was great. There were a lot of really fit tanned boys and some of them looked at me in my new bikini, but then they looked at Gran and kept away. But I felt really shy and embarrassed and wished I had a more cover-up cossie. Having a figure is only nice when you’re showing it off to other girls – that’s what I thought, I didn’t like those boys eyeing me up and down.

We went out for dinner to a posh restaurant. It was in a tower that revolved while you ate – you could look at the lights coming on, and the stars shining on the river. They served cooked kangaroo, which Gran ate, but I wouldn’t – I thought it was awful, like eating a horse or a dog. I had steak. I suppose that’s just as bad, really. I fell asleep in the middle. I was really dopey. Gran said it was OK, she was like it herself. She said everyone gets jet lag and that I’d be better in a day or two.

She was right. The next day I felt great. She said tomorrow we were going travelling and I was going to see the outback, like I’d wanted. Of course I thought it would be some kind of day trip. I was so excited. I was loving every minute. I thought Gran was the greatest. She kept hugging and kissing me. She always had, but now I hugged her back. I felt I really loved her, I was just so grateful.

That evening Gran told me she had things to do in the morning, and that I was to pack and meet her in the lobby. “I’m ordering room service to bring you a lovely brekky in your room, then just come on down at ten. Don’t you try to stagger down with your bags, precious,” she said. “I’ll send a bellboy. See ya!” I thought she had a funny smile, as if she had a surprise for me. Boy, did she.

When I came out of the lift next morning, I looked all round this vast lobby, but I couldn’t see her. There was a tall man in a big-brimmed leather hat standing at the reception desk. My eyes went right past, still looking for Gran. Suddenly the tall man turned round. I got a real shock.

It wasn’t a man, it was her! But even facing, I hardly recognised her. She’d changed her clothes. Her clothes? She’d changed everything. She was wearing combat trousers, a khaki shirt, and cowboy boots. She looked completely different. Even her blue hair was covered with the leather hat. She looked like Crocodile Dundee.

I came up to her slowly. “Gran, is it you? What have you done to yourself?”

She laughed, a big boomy laugh. “Well, sugar-puff, we’re off to the bush! You don’t expect me to doll myself up in town clothes for that, do you? Didn’t I tell you there are two of me, a town person and a bushie? This is your bush Glendine!”

While we’d been in Perth we’d driven around in taxis. Now we went outside and waiting at the front of the hotel was one of those truck-things with an open back. Her luggage was piled in that, with a whole lot of other stuff. I thought I saw a sort of iron bed! The bellboy came along with my luggage and put it in with the rest, and helped Gran pull a piece of canvas over everything and tie it down. Gran said, “How d’you like my ute?”

“Ute?”

“Utility. That’s what we call ‘em.”

“Did you say it’s yours?”

“Sure. I’ve had it in a garage while I’ve been in London. They brought it to me this morning and I’ve been off to do a bit of shopping.”

I looked at it. It was about the last kind of vehicle I’d’ve expected her to drive. To begin with I was surprised the doorman let her stand it outside the hotel, it was so rusty and old. It looked as if it might drop to pieces any minute and have to be dragged away.

There was a big metal bar in front.

“That’s a roo bar,” said Gran.

“Rhubarb?”

“No! Roo bar! It’s so if you hit a roo – kangaroo – he doesn’t damage the car. Hitting a roo can cause an awful dent to your ute.”

I said, “Oh, please, don’t hit one, Gran!”

She laughed and said, “They’d better keep out of my way then.”

I soon saw what she meant.

We climbed up into the cabin. The seat covers were so worn the stuffing was coming out. It was a mess inside – big bottles of water everywhere and dangly things in the windows, and rubbish on the floor. I said, “What would they think of this in Singapore?”

Gran let out a kind of whoop of laughter. “They’d beat me to death!” She sounded happier than I’d ever heard her.

Then she just took off.

I’ve never seen anyone drive so fast. Even going through the town, I had to hang on tight. I was breath-stopped and it was only through good luck we weren’t cop-stopped. When we got out on the country roads she zoomed along like someone lit her fuse.

“Gran, slow down!” I yelled.

“No fear, lovie! We’ve got a long way to go!”

Luckily after a bit we got on to a road with almost no traffic. I say “luckily” – it wasn’t really, because then she went faster than ever.

At first there was forest on each side that seemed to go on for ever, but after that was even more for ever with what looked like sheep and wheat farms. It was endless, endless driving. I got sort of hypnotised by the long, dead straight road. Passing another vehicle was an event. There were a few enormous, humungous trucks with two or three containers attached. Gran called them road trains. But there wasn’t much else on the road at all.

Then it changed. On either side were low banks of bright red earth, and trees and bushes, sort of greyish-green, not like English ones. It just went on and on, mile after mile the same. I said to Gran, “Is this it – the bush?”

“Well, you know what they say! The bush is always 50 k on from wherever you are! But I’d call this the beginning of it.”

I said, “I thought it would be more, like, desert.”

“This is a sort of desert. It’s very dry. But it’s full of life. Snakes, goannas, emus… This is roo country. That reminds me, I should slow down now.” And she did. “I have to watch out for them because they’ve got no road sense. They just bound right out on to the road.”

I saw a lot of birds fly up from a lump on the roadside. “Oh, look!” I said, pointing. “Is that a dead one?”

“Yeah. He’s just roadkill now, poor old thing. And that was a wedge-tailed eagle, eating him,” she said, pointing to a huge bird that was flapping away. An eagle! It gave me a kind of shiver of excitement to see a real eagle.

I kept looking for live roos but I didn’t see one. I was glad. I didn’t want one to jump out in front of us and get hit. I saw more dead ones, though, and there were waves of stink in the air.

On and on we drove. At times I thought I might be getting bored, but there was always something new to see. The trees were sort of wonderful. I’d never seen anything like them at home. Gran said, “Pretty well everything here is different from everything anywhere else. It’s because Australia was cut off from the rest of the world, millions of years ago, and different kinds of plants and animals evolved. That’s what makes this such an exciting, wonderful place. Aren’t you glad I brought you?”

Well, I was. At least, I had been, till now. Now we were driving alone through the bush in this clapped-out rusty tin can, which I kind of thought might break down, and Gran had changed. I began to feel just a little bit uneasy. It was pretty obvious we weren’t going back to the hotel that night. Maybe not at all.

After about five hours, when I was stiff and starving, we stopped in a little town. It was so different from Perth! Perth is like any big city (only a lot nicer, certainly than London). This was like something out of an old Western movie, except for all the utes parked along the street instead of horses. The buildings had those funny wooden fronts, and the men walking around looked kind of like cowboys, in a way. Gran parked outside a bar and we went in. I was sure someone would say I was too young, but nobody took any notice. There was hardly anyone in this bar place, and it was dark and dreary. As soon as I walked into it, I wanted to leave, but I needed a pee like mad and by the time I got back Gran’d ordered hamburgers and some Cokes. I counted the cans. Five. I looked around to see if anyone else had joined us.

“Who are all the Cokes for, Gran?”

“One for you, four for me. Or, if you’re really thirsty, two for you and then I’ll have to order another for me.”

I’d never seen anyone drink like she did. She just poured it down as if she didn’t have to swallow. At the end of each can she’d smack her lips and pick up the next.

“What I couldn’t do to a beer!” she said. “But don’t you worry, sweet-pants. I’m just rehydrating myself. I wouldn’t drink and drive.” I didn’t say anything. I knew my dad sometimes had, even though he’d never been stopped. Mum used to totally panic… Of course, that was when we had an old banger. Needless to say, he took it with him when he left us.

We set off again. I asked where we were going. You’ll think it’s about time I thought to ask that, but up till then I’d just been kind of going with the flow. I’d got out of the habit of asking questions.

She shouted above the motor, “Can’t you guess? We’re going to my station.”

I gawped at her. I was thinking railway or tube stations, like, Peckham Rye (ours), or Hammersmith (Nan’s) or Waterloo. “You’ve got a station?”

“Course I have! I told you about it.”

She hadn’t. She had not. She’d never mentioned a station. I’d have remembered.

I’d have asked her to tell me more, but the motor was roaring and I felt too exhausted. The country was more like desert now. There weren’t so many trees, just these low bushes and big tufts of tall grey grass. There wasn’t much to look at, and it was getting hotter and hotter. And dustier. I kept washing the dust out of my throat with one of the big water bottles. At last I fell asleep.

Gran woke me up. It was dark. We must’ve been driving all day.

“Right, Stacey-bell, out you get and help me make a fire.”

I slid out of the cabin and almost fell over a pair of wellies. “Put those on,” said Gran. “And take this torch. There’s lots of wood around. But be sure you kick it before you pick it up.”

“Why?”

“Why d’you think?”

I had no idea why anyone would kick wood. But as I was taking my sandals off to put on the rubber boots, a terrible idea came into my head.

“Gran! Are there snakes around here?”

“There might be. But just remember, the snake that bites you is the one you don’t see, so keep a lookout.”

Oh my God. I nearly fainted. I already said how I hate snakes. I’ve always had a thing about them. I don’t know why because, like I said before, I’d never seen one. They just give me the creeps.

I shot back into the cabin of the ute and sat there shivering with my legs tucked up, imagining loads of snakes coming slithering right up the step and on to the ute floor. Gran came round to my side. “Get out, Stacey,” she said. I think that was the first time she’d called me by my name and not some nickname. And it was the first time I’d heard her use an ordering tone to me. When I still didn’t move, she said, “Don’t be such a pom.”

“What’s a pom?” I asked. My teeth were chattering. Honest to God, they were.

“An English person is a pom. Poms have a bad name with us Aussies for being whingers. I’m not having a whingeing pom for a granddaughter. Now get these boots on your feet and get me some wood or there’ll be no food.”

“I don’t want any. I want to go back to sleep.”

“We’ll make up the beds when we’ve eaten.”

“What beds? I’m not sleeping anywhere near the ground!”

“You’re sleeping in the back of the ute. Nothing can get at you there. Come on, now, hurry up, I’m starving.” When I still didn’t move, she said, “We must make a fire to keep the dingoes away.”

I knew dingoes were wild dogs. Dingoes are fierce. I’ve read about it. They eat babies.

I thought of those movies about African safaris or American cowboys where the campfire keeps wolves and other dangerous animals from coming near. I was so scared, thinking of wild dogs creeping up on us, I almost forgot about snakes. But Gran was just standing there, sort of tapping her foot. I couldn’t just sit there scrunched up all night. I was a bit hungry, come to think of it. And except for the torch, it was pitch dark. A fire would be good. I slowly unscrunched and stuck my feet out. Gran very briskly pushed the wellies on, then pulled me out and put the torch into my hand.

“Go,” she said, turning away.

I shone the torch around and right away I saw some dead wood lying quite close by. I kicked it hard, twice. Nothing popped out. It was a real effort to make myself bend down and snatch up a branch with my finger and thumb. Then I had to walk over to where Gran was digging a sort of pit with a big flat shovel. I shone the torch in front of my boots all the way.

“Here’s a piece,” I said, dangling it.

She stopped and squinted at it as if it was so small she couldn’t see it. “Oh, that’s amazing,” she said. “Do you think you could possibly find me another one just like it? Then we can rub them together and make sparks.”

I dropped the piece and shone my way back to the pile I’d taken it from. I kicked it again. Bit by bit I carried or dragged all the wood from it to where Gran was. She’d pulled up some of the dry grass tufts and before long she’d got a fire going. (Using matches of course. I should’ve known she was having me on.)

The wood was dry and it really burnt a treat. It was weird how much better I felt as soon as it blazed up. She kept me at it till we had a good woodpile – I had to go further than just right next to the ute to get enough. I kept kicking the wood but there were no snakes and after a bit I got so I wasn’t scared to death. I still felt pretty brave though, going off into the dark like that by myself. Once I went about three whole metres from the fire.

By the time Gran was satisfied we had enough wood, there were some hot embers. She scooped them up with the shovel and put them in the pit she’d dug. Then she said, “Now be a love and bring me the Esky.”

I wasn’t really speaking to her at this point, and I felt silly, asking “What’s this” and “What’s that” all the time, so I went to the back of the ute. I’d no idea what an Esky was, but I soon guessed, because what do you put food in if it’s going to be shone on by the sun all day? One of those cold-box things, right? And sure enough there was one. It was dead heavy. I couldn’t get it over the side of the ute so then I noticed there was a kind of catch on the ends of the ute-back. When I slid them, the back fell down with a crash. After that I could drag the Esky off and lug it back to the fire.

Gran opened it and inside were six packages wrapped in foil, along with some milk and tins of Coke. She laid the packets on top of the red embers, then she shovelled more embers on top. The whole thing glowed like an electric stove-plate. She covered the red place with earth and then she got out a thermos and we had some coffee. It was still warm, and sweet. I never drink coffee at home but I drank a big tin mugful.

“That’s your pannikin,” she said. “I’m giving you that. You can even put it on the fire if you want to heat it up.” But I just drank it as it was. The pannikin was pretty, sort of mottled red, and I didn’t want the bottom to get burnt, if it was my present. I reckoned I’d earned it, being brave about the snakes and that, and collecting lots of wood.

Then Gran said, “What’s that blood on your arm?” Later I wished I’d said, “Oh, nothing, it’s just where a dingo bit me,” but I just muttered it was a scratch from a sharp bit of wood. She looked at the cut and said, “Well, a whingeing pom would’ve whinged about that, so good on you.” She squeezed it and said, “Good, there’s no splinters left in there.” Then she got out a jar and started smearing something on the cut.

“What are you putting on it?”

“Honey.”

“Honey!”

“Sure. Didn’t you know honey’s an antibiotic?”

“Why do I need an antibiotic?”

“Because that’s mulga wood and if you get it stuck in your flesh, it’s poisonous.”

My mouth fell open – again. Poisonous wood? Was there anything safe in this place?

The food took quite a while to cook in the embers. At last a really good smell started to come out of the ground. By the time Gran dug the food out I was like dying of hunger. She’d got two plastic chairs off the ute, and a little folding table, two plastic plates, and knives and forks. And some butter and salt. Gran dusted the ashes off the foil and opened the packets. Inside were big chicken legs, baked potatoes, and cobs of sweet corn. We didn’t bother about the knives and forks in the end, we just ate with our fingers by firelight. It tasted well delicious. I drank Coke and she drank beer. Then she stood up and stretched and said, “Right. Bed.”

She made me close the Esky and pack all the stuff away in a box. I thought I’d better burn the chicken bones in case they brought the dingoes. The fire was dying down. Nearly all my wood was gone. I said, “Who’s going to keep the fire going?”

She said, “Well it’s no use looking at Glendine. She’s going to make big Zs.”

I said, “But if we don’t, the dingoes’ll come!”

She said, “You’re an easy mark, Stacey. There’s no dingoes around here. Now help me with my bed.”

I didn’t say anything. I helped her lift a rusty old iron bed with fold-back legs and a mattress off the back of the ute, and she set it up. It wasn’t far off the ground… There was another mattress left on the floor of the ute for me. Then she untied two bundles.

“Here’s your swag,” she said. A swag turned out to be a sleeping bag. She had a pillow for me, too. She made up her own bed with another swag. I said, “I need to go to the loo.” I know I sounded sulky. I couldn’t believe it about the dingoes, that she’d do that just to make me get out and help.

She picked up the shovel and the torch. “Go ahead,” she said. “Over there, by those trees. Keep downwind, ha ha.”

I stared at the shovel, thinking what it meant. I had to dig a hole, and— No. It was too gross. Though how else? We were a million miles from anywhere. It looked to me like even the trees were about a hundred miles away from the little circle of firelight where the ute was. Where Gran was.

“Was it true about the snakes?” I said.

“Lovie, would I lie to you? Of course there are snakes in the outback. Just keep shining the torch and stay where the ground’s open. Oh, here’s some dunny paper. Be sure to bury it, too. Now go on and do what you have to do.”

Grandpa used to say, “Needs must, when the devil drives.” So I did it. I managed somehow. But the walk there into the darkness was the worst thing I’d ever done, even worse than when our diving teacher made us dive into the school pool over her arm the first time.

I was beginning to change my mind about Gran being the greatest. That’s putting it nicely.

Chapter Four

When I ran back to the ute, she was lying on her swag on her bed fast asleep. She hadn’t even undressed. I noticed she’d left her boots on one of the plastic chairs. I rinsed my hands and face with water from the bottle, swilled out my mouth, set the other chair against the back of the ute and climbed up. I didn’t know whether to undress or what, but my night things were all in my case, so I just dropped my boots over the side and lay down on my swag just as I was. There was a bit of a breeze which made it not so hot. I wished the back of the ute wasn’t down, I’d’ve felt safer with it up. I struggled with it a bit in the dark but I couldn’t lift it. If I’d let myself, I could’ve easily imagined dingoes sniffing me, or… But I fell asleep straight away.

In the night I woke up. It was light that woke me. It’d been completely dark but now there was a pale light all over everything. I lifted myself on my elbows to look and there was the moon, or half of it, just a bit above the horizon but already lighting up the bush and us and everything. There were spooky tree-shapes all around the clearing where we were. I noticed the silence. Total. No birds or anything. It’s never, ever that quiet in London.

I lay back down and looked at the sky. Stars! You couldn’t just say there were stars, like it was something ordinary. I’d never seen anything like those stars in my life. Billions – and that’s no exaggeration. The more you looked at the bright ones, the more tiny little faint ones you could see in between. There didn’t seem to be an inch of sky without any. Right overhead there was a thicker path of them. It stretched from one side to the other, like someone had splashed some milk. Suddenly I realised that must be the Milky Way. I’d heard of it but I’d somehow never thought it was real – I thought it was, like, something in Star Trek.

There was something so scary about that bigness. I couldn’t look at it for long. I had to shut my eyes and pretend it wasn’t there because I just felt sick to my stomach from all that emptiness with me tiny and helpless underneath it. I filled my own darkness behind my eyelids with Mum’s bedroom and Mum’s bed with Mum snoring beside me.

Then some real snores started. Gran’s. That was some comfort. After a bit I dozed off, but I had terrible, scary dreams. The Milky Way turned into a big white snake, coming out of the sky to get me.

In the morning, bright sunlight and bacon smells woke me.

Gran was tending the fire. There was a blackened old kettle on one bit of it and a blackened old frying pan on the rest. She’d made up a new woodpile. I looked at my watch. It was five thirty. There were plenty of birds about now. They were going mad in fact.

“Hello, Gran,” I said, kind of dopily. It seemed funny we were still here and that I wasn’t scared any more.

“Hi there, Stace, how are you going? Sleep well?”

“Sort of.”

“Want your coffee in bed? Billy’s boiling.”

I didn’t even think “Who’s Billy?” I could see that “Billy” was the kettle, and I remembered some song when I was a little kid about “he sang as he watched and waited till his billy boiled”, and how I used to think it was his willy that was boiling. I giggled and hiked myself up, leaning my back against the cabin. I just sat there all peaceful, looking around again. There was nothing scary about the bush by daylight, it looked beautiful. The colours were red, for the ground, and a sort of greyey-green for the grass tufts (I found out later it’s called spinifex), and brown for the tree trunks. Not all the mulgas were dead, some had leaves on them. And the sky was a gorgeous dark blue. Would you believe the sun was hot already? Gran handed me up my pannikin full of fresh hot coffee.

“Get a swig of that into you and then jump down for breakfast. It’ll be ready in a minute.”

I wanted to get down right away. I felt suddenly all hot and uncomfortable and I needed to go. I put the pannikin on the roof of the cabin and started to scramble over the side of the ute. Suddenly Gran said, “Hey! Have those boots been on the ground all night? Wait right there.” She came and picked them up and shook them, open end down. Something dropped out of one of them.