Полная версия

Statecraft

Don’t believe that military interventions, no matter how morally justified, can succeed without clear military goals

Don’t fall into the trap of imagining that the West can remake societies

Don’t take public opinion for granted – but don’t either underrate the degree to which good people will endure sacrifices for a worthwhile cause

Don’t allow tyrants and aggressors to get away with it

And when you fight – fight to win.

MILITARY PREPAREDNESS – MATÉRIEL

Whatever cosy euphemisms we may want to adopt, defending our interests in battle is what our armies, navies and airforces ultimately exist to do. They are not well-suited to act as policemen, aid workers or civil engineers, and they should not be required to do so, except under extreme and temporary circumstances. They need the weapons to deter and destroy any enemy they may be called upon to face. They need to be well-trained, well-disciplined and well-led. And they need to be able to rely on wise and determined governments to see that the financial and other conditions under which they operate are conducive to these goals.

Democracies are actually quite good at fighting wars – as a series of dictators over the years have learned to their cost. Where democratic political leaderships are weak, however, is in their capacity for continuous military preparedness. Such weakness leads to unnecessary conflicts, because it undermines the will, and can exclude the means, to deter aggression. It also leads to wars being longer and more costly than they would otherwise be, because it takes years to build up the military might required to defeat an aggressor.

The end of the Cold War was in these respects more typical than the end of the Second World War. The defeat of the Axis powers evoked a huge sigh of relief. But it also brought the West to the very edge of a new conflict with the Soviet Union. Once it was known that the Soviets had the atomic bomb, it was clear to all but the very foolish and the fellow-travellers that military preparedness was the precondition for the West’s survival.

The end of the Cold War was quite different. International utopianism became the rage. As at the end of the Great War, there was a marked preference for butter not guns.

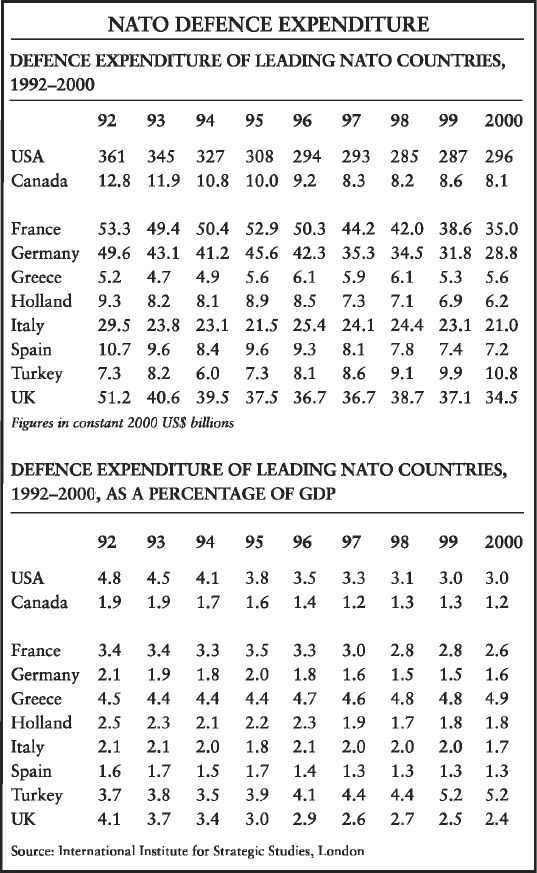

The figures for defence spending show this.* They demonstrate that America cut too far and that Europe was even worse. The West as a whole in the early 1990s became obsessed with a ‘peace dividend’ that would be spent over and over again on any number of soft-hearted and sometimes soft-headed causes. Politicians forgot that the only real peace dividend is peace.

America’s defence budget decreased every year from the end of the Cold War until 1998–99. It now stands at about 60 per cent of its peak of 1985. And this occurred during a period in which public expenditure on all other sectors of the federal budget rose. As a result, American active and reserve military forces in 2000 were more than a million below the levels reached in 1987. The Clinton administration reduced the number of active army divisions to ten, from the eighteen divisions under the Reagan administration. It reduced the airforce by almost half from the Reagan levels. And it reduced the number of naval ships and aircraft carrier battle groups by almost 45 per cent. Moreover, there was a severe shortfall in recruitment of service personnel – the US Navy missed its recruiting goal by nearly seven thousand in 1998.†

This steep decline in US military spending was more than mirrored elsewhere in NATO. Germany, Spain and Italy spend less than 2 per cent of their GDP on defence, while America spends 3 per cent. Put another way, the United States spent $296 billion on defence in 2000, compared with the European NATO members’ total contribution of just $166 billion. The Europeans have cut defence by 22 per cent in real terms since 1992, and they are still cutting.

Furthermore, as the International Institute for Strategic Studies notes in its 1999/2000 Strategic Survey: ‘Much of what is spent by European governments goes not towards new technology or better training, but towards the costs of short-term conscripts, pensions and infrastructure.’ European countries are not going to be able to match the United States at the cutting edge of military technology. (That is, of course, a further reason why they are not going to have the ability to field an effective European Union defence force.) But at least they can stop wasting resources on maintaining conscript armies that are inadequately trained and lack all credibility as fighting forces.

In America the dangers of underfunding defence have now been widely understood. Already under President Clinton (and also under pressure from the Republican-controlled Senate) the administration had begun to increase defence expenditure once more from the beginning of fiscal year 2000. In 1999 Congress also approved the first major increase in military pay since 1982 in order to improve recruitment. The new administration’s strong commitment to increasing America’s defence capability will doubtless also lead to further improvements. And doubtless lessons will be learned from the operations in Afghanistan.

By contrast, the European countries still demonstrate little or no sense of responsibility for upgrading the Alliance’s defence effort. Wealthy European Union countries like Germany and Italy have been cutting, not increasing, their already low levels of military expenditure.

Military planners always have a thankless task. In peacetime they are accused of dreaming up unnecessarily ambitious war-fighting scenarios, and then demanding the money to pay for them. But when dangers loom, they are criticised for insufficient foresight. Moreover, a global superpower’s military planners have a special problem. This is that a major threat to stability in any region is by definition a threat to the superpower’s own vital interests. And the nightmare is that several serious regional conflicts may occur simultaneously. To the question of what precise overall capabilities, and thus exactly what levels of defence spending, are necessary to cope with such scenarios I can only answer: ‘More than at present – and possibly much more than you think.’

So I conclude:

The West as a whole needs urgently to repair the damage that excessive defence cuts have done

Europe, in particular, should sharply increase both the quantity and the quality of its defence spending

The US must ensure that it has reliable allies in every region

Don’t assume that crises come in ones or even twos

Don’t dissipate resources on multilateral peacekeeping which would be better husbanded for national emergencies

Whatever the diplomats say, expect the worst.

MILITARY PREPAREDNESS – MORALE

Western politicians have also been failing our armed forces in another important respect. They have either championed, or at least failed to counter effectively, pressures to alter fundamentally the traditional military ethos.

The tasks of war are different in kind, not just degree, from the tasks of peace. This does not, of course, mean that the laws of commonsense – or indeed Parkinson’s law – are suspended in military matters.* Defence procurement programmes must be efficiently managed. Functions which can sensibly be contracted out should be. Unnecessary non-military assets should be sold. Reviews and scrutinies will be necessary to remove duplication and waste. These concepts were ones which I sought to ensure were applied when I was Prime Minister, and they are of universal application. But, for all that, it has also in the end to be recognised, I repeat, that the military is different.

One very obvious reason is that the defence budget is one of the very few elements of public expenditure that can truly be described as essential. The point was well-made by a robust Labour Defence Minister, Denis (now Lord) Healey, many years ago: ‘Once we have cut expenditure to the extent where our security is imperilled, we have no houses, we have no hospitals, we have no schools. We have a heap of cinders.’* For this reason, if the Chief of the Defence Staff (or his equivalent) declares that without certain military resources the country cannot be adequately defended only a fool of a politician refuses to listen.

But the military is also different because service life is different from civilian life. The virtues which must be cultivated by those who may be called upon to risk their lives in the course of their duties are simply not the same as those required of a businessman, a civil servant – or, indeed, a politician. Above all, courage – physical courage – is vital.

Servicemen need to develop a much higher degree of comradeship with their colleagues. They must be able to trust and rely on one another implicitly. Soldiers, sailors and airmen are still individuals – one has only to read their biographies to understand that. But they cannot be individualists. For those who live under discipline it is duties not rights that are the focus of their lives. This is why the military life is rightly considered a noble vocation, and also why over the years many of those who leave it for civilian careers find it difficult to adjust.

Soldiers also generally need to be physically strong. It is not enough to be clever – though to be cunning is certainly useful. No front-line forces can afford to have even a small proportion of their number who are not up to whatever tasks they may be called upon to perform.

So I am opposed to current attempts to apply liberal attitudes and institutions developed in civilian life to life in our armed forces. Programmes aimed at introducing civilian-style judicial systems, at promoting homosexual rights, and at making ever more military roles open to women are at best irrelevant to the functions that armies are meant to perform. At worst, though, they threaten military capabilities in a way that is actually dangerous.

The feminist military militants are perhaps the most pernicious of these ‘reformers’. The fact that most men are stronger than most women means either that women have to be excluded from the most physically demanding tasks, or else the difficulty of the tasks has to be reduced – something that is evidently easier in training than in combat. But it is, of course, this second course which the feminists demand should be adopted. And all too often their agenda is being accepted.

When it was recognised that women cannot throw ordinary grenades far enough to avoid being caught in the explosion, the answer was not to let men take over but rather to make lighter (and less lethal) grenades. When it was discovered that women on board warships require facilities that men do not, the US Navy had to ‘reconfigure’ their ships to provide them – on the USS Eisenhower alone that cost $1 million. And when most women (rightly in my view) choose not to take combat roles, the answer, according to one professor at Duke University, is for the military to get rid of traits like ‘dominance, assertiveness, aggressiveness, independence, self-sufficiency, and willingness to take risks’.* Women have plenty of roles in which they can serve with distinction: some of us even run countries. But generally we are better at wielding the handbag than the bayonet.

And warfare will always involve the use of bayonets, or their equivalents. It is unrealistic to expect that wars will ever be fought without physical contact and confrontation with the enemy at some stage.

With these considerations in mind, our political and military leaders should:

Show some backbone in resisting the lobbies of political correctness that are out to subvert good order and discipline in our armed forces

Make it plain that life in the services cannot take as its model the behaviour, legal framework, or ethos that prevail in civilian life

Refuse to put liberal doctrine ahead of military effectiveness

Demonstrate a little commonsense.

RMA

That said, we have reached one of those points in military history when the role of technology in fighting wars has taken on an altogether new importance. The Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) is a real revolution. The term refers mainly to two developments: the power of instantly available, networked information, and the large-scale use of precision firepower. One of the foremost experts on the strategic implications of RMA, Professor Eliot Cohen, has graphically described its reality:

Satellites beaming fresh pictures of targets to pilots in jet aircraft, tanks communicating their locations to computerized command posts, generals peering remotely over the shoulders of company commanders through the cameras of orbiting unmanned aircraft – these are all phenomena of today, not the military dreams of tomorrow.*

America is and will remain far ahead of any of her rivals in the use of these technologies – as long as she keeps on investing in them.

But RMA is not without its drawbacks. I have already referred to one of these – a feeling that technology can make war casualty-free. A more tangible danger is what (in the jargon) are called ‘asymmetric threats’. By these are meant threats posed by powers which, although generally lagging well behind America militarily, are able to concentrate their resources upon and exploit American vulnerability in one particular aspect of warfare. Thus China has on its own admission been developing plans to use networks and the Internet to cripple America’s banking system and disrupt its military capability.* Information- or Cyber-warfare has leapt from the television screen to the centre of the Pentagon’s preoccupations. That is absolutely right. It is a rule as old as warfare itself that every advance in military technology provokes counter-measures. And history is full of rich and technologically advanced civilisations which fell before a more primitive enemy who had seen and exploited a systemic weakness.

That is why we have to:

Give top priority to investing in and applying the latest defence technologies

Be alert to the dangers that America’s technological sophistication could be undermined by asymmetric threats from a determined enemy

Never believe that technology alone will allow America to prevail as a superpower.

‘REMEMBER PEARL HARBOR’

Before, during and after my time as Prime Minister I have paid many visits to American military bases and other sites, but none like that which I made to the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor on the morning of 11 May 1993. A tender took us out to the ship, upon whose shattered hull a special structure has been erected. For the last forty years, the colours have been raised and lowered each day in honour of the 1177 members of the Arizona’s crew who died in the Japanese air force’s attack of 7 December 1941. Some of the bodies were recovered, but the remains of nine hundred still lie in the depths of the water that now fills the ship. Standing over a square opening that leads down to the ocean, I lowered a bouquet of flowers. The petals drifted across the surface and I thought about the sailors who died in such terrible circumstances so that the rest of us could live in peace and freedom.

The USS Arizona should not only, however, be a place of pilgrimage: it should be a place of reflection. The immediate consequence of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor was, of course, to bring America into the Second World War. So it was, in that sense, the day the Axis powers began to lose. The circumstances of the attack swung an earlier sceptical American opinion behind the war effort. ‘Remember Pearl Harbor’ became the title of America’s most popular war song. Those words should also serve as a warning to us.

On that Sunday morning sixty years ago, just before eight o’clock, 353 Japanese aircraft began their devastating attack. Some three thousand military personnel were killed or wounded, eight battleships and ten other naval vessels were sunk or badly damaged, and almost two hundred US aircraft were destroyed in the space of just three hours. What made the attack on Pearl Harbor so shocking was the fact that it was entirely unexpected. Tension between America and Japan had been rising. But there was no suspicion of what the Japanese were planning and there had been no declaration of war. The inquiries launched after the event found that errors had been made by the US naval and army commanders in the Hawaii region. But the fact remains that what happened at Pearl Harbor reflected far more broadly on the unpreparedness of America for an attack coming (literally) ‘out of the blue’.

The colours raised over the Arizona on the day of my visit were given to me when I left by the Commander-in-Chief of the US Pacific Fleet. They are now framed in my office in London. They serve as a constant reminder. What troubles me, however, is that America and her allies now face a similar threat, and we have been doing too little to guard against it.

MISSILES AND MISSILE DEFENCE

The lessening of superpower rivalry in the final stage of the Cold War also resulted in a loosening of superpower disciplines. On the one hand, Soviet political satellites were released to seek their own irregular and eccentric orbits. On the other, as the Soviet Union itself crumbled, its weapons stockpiles were dispersed and plundered, new clients were found for weapons production, and existing experts with knowledge of advanced military technologies abandoned a state that could no longer pay its bills.

Saddam Hussein’s aggression against Kuwait in 1990 occurred a little too early for him. He had not quite been able to acquire the weaponry he needed to strike back at the West – his plans to develop the nuclear weapon having been seriously set back by Israel’s pre-emptive attack in June 1981. But if Saddam had been in a position credibly to threaten America or any of its allies – or the coalition’s forces – with attack by missiles with nuclear warheads, would we have gone to the Gulf at all? Just posing that question highlights how fundamentally the reality of proliferation can affect the West’s ability to exert power beyond our shores.

Subsequent experience in dealing with Saddam Hussein should also bring home to us the difficulty of trying to maintain a united front against proliferators – even against a rogue whom everyone in public characterises as a pariah. The recent book by Richard Butler, former head of UNSCOM, the body commissioned to inspect and eliminate Saddam’s weapons capability, provides new insights into how China, and in particular France and Russia, have played fast and loose with their international obligations. The Russians clearly still view Iraq as their gateway to the Middle East and the Persian Gulf, while the French have huge commercial interests in the Iraqi oil industry. All three powers have been driven by what Mr Butler calls ‘a deep resentment of American power in the so-called unipolar post-Cold War world’.* If this is a precedent for international cooperation in such matters it would be better to pursue other channels.

The more general, and even more important, lesson from experience in dealing with Saddam is that it is extremely difficult to prevent states that are determined to acquire weapons of mass destruction (WMD) from doing so. If it is so hard to monitor and control the activities of a country like Iraq, which has been defeated in war and subjected to repeated threats, sanctions and punishment, what chances are there of preventing the proliferation of WMD among states that are much less subject to scrutiny?

In fact, proliferation has proceeded, often assisted by the failure of the West to check the outflow of technologies. Nor have international arms control agreements helped much in this respect. The Biological Weapons Convention has been unsuccessful in preventing the development of this particularly horrible weapon, because its provisions are for all practical purposes unverifiable. The same is true of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

These agreements, though, are at least more or less neutral in their effects. The same cannot be said, however, of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which the United States Senate rightly refused to ratify. The fundamental truth here is that the nuclear weapon cannot be disinvented. A world without nuclear weapons is thus quite simply a fantasy world. The realistic question, therefore, is whether the West and America wish to stay ahead of potential nuclear competitors or not. If we do not, we hand power over regions where our interests are at stake to the Saddams and Gadaffis and Kim Jong Ils.

Faced with that prospect it is easy to see why America’s nuclear deterrent must be completely credible, which means that it has to be tested and modernised as necessary. We should have learned by now that no weapons technology ever stands still. For every idealistic peacemaker willing to renounce his self-defence in favour of a weapons-free world, there is at least one warmaker anxious to exploit the other’s good intentions. All those who shelter beneath the American nuclear umbrella should have been praising Senator Helms and his colleagues who defeated the CTBT – not having tantrums.*

Moreover, in the end nuclear weapons will probably be used. That is a terrible thought for everyone. It is also a novel thought for many who argued, as I did, during the 1970s and 1980s for an up-to-date deterrent as a means of keeping the peace.

During the Cold War’s ‘balance of terror’ it was always possible to argue that because both sides had powerful nuclear arsenals this provided an important stabilising factor, preventing not just nuclear but conventional war, at least in Europe. In truth, there was never any cast-iron guarantee against a nuclear exchange. We knew that we would never initiate a war of any kind against the Warsaw Pact. And we had good reason to believe that the Soviets would be too cautious to launch a nuclear war against the West. But we could never altogether rule out the possibility of miscalculation or technical error precipitating an exchange.

Since the end of the Cold War, it has been possible to cut back nuclear arsenals substantially, and it may be possible for America and Russia to cut back still further. But we should not forget that the START II and the proposed START III treaties, like earlier arms control (and, as in these cases, arms reduction) agreements, do not in themselves actually make us more secure. What they do is reduce the cost of our security, by lowering expenditure on surplus weaponry, and they arguably help ease tensions and mistrust. The last point is about all that can be said for agreements about the targeting of missiles – which can always be re-targeted.

With the end of the Cold War we entered what one leading expert has provocatively termed ‘the second nuclear age’. Among the fallacies which Professor Colin S. Gray lists as afflicting Western strategic policy planners today are that ‘a post-nuclear era has dawned’, ‘nuclear abolition is feasible and desirable’, and ‘deterrence is reliable’. He has also warned that ‘the less strategically attractive nuclear weapons appear to the United States, the greater the attraction of those weapons and other WMD to possible foes and other “rogues’”.* And he is right.

The most important threat of this sort today does indeed come from the so-called ‘rogue states’. This category usually refers to medium-sized (or even quite small) powers in the grip of an ideology (or of an individual) that shuns the existing international order, and is bent on aggression. The usual candidates are Iraq, Iran, Libya, Syria and North Korea, all of which should certainly be included, as in the light of recent events should Afghanistan.* But we should not disregard either the chilling remark of a senior Chinese official made in 1995 at the height of confrontation between China and Taiwan. The official noted sarcastically that Beijing could take military action against Taipei if it wished, without worrying about US interference, because America’s leaders ‘care more about Los Angeles than they do about Taiwan’. Perhaps the Chinese too remember Pearl Harbor.