Полная версия

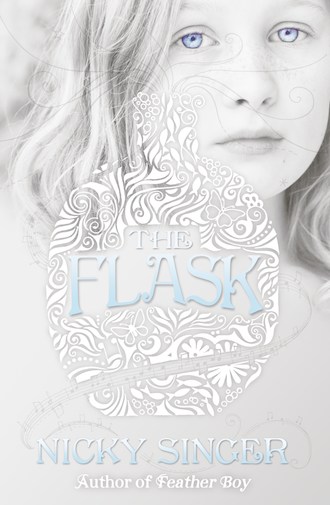

The Flask

I’m thinking all this as I select a drawer for my father’s ivory slide rule. Right or left? I choose the right, slip it in. Then I change my mind.

I just change my mind.

I open the left drawer and transfer the slide rule. But it won’t go, it won’t fit. I push at it, feel the weight of its resistance. I push harder, the drawers are an equal pair, so what fits in one has to fit in the other.

Only it doesn’t.

I pull out the right-hand drawer. It runs the full depth of the desk, plenty long enough for the slide rule. I pull out the left-hand drawer. It is less than half the length of its twin. Yet it isn’t broken. It is as perfectly formed as on the day it was made.

Which is when I put my hand into the dark, secret space that lies behind that drawer.

And find the flask.

My heart gives a little thump. I’ve no idea, this first time, what I’m touching, except that it is cold and rounded and about the size of my hand. As I draw it out into the light, I feel how neatly its hard, shallow curves fit into my palm.

I call it a flask, but perhaps it is really a bottle, a flattish, rounded glass bottle with a cork in. It is very plain, very ordinary and yet it is like nothing I’ve ever seen before. The glass is clear – and not clear. There are bubbles in it, like seeds, or tiny silver fish, swimming. And the surface has strange whorls on it, like fingerprints or the shapes of contour lines on a map where there are mountains. I think I should be able to see inside, but I can’t quite, because the glass seems to shift and change depending on how the light falls on it: now milky as a pearl; now flashing a million iridescent colours.

I sit and gaze at it for a long while, turning it over and over in my hands, watching its restless colours and patterns. It is a beautiful thing. I wonder how it came into being, who made it? It can’t have been made by machine, it is too special, too individual. I remember the glassmaker who made my green cats and I imagine a similar man in a leather apron blowing life down a long tube into this glass, putting his own breath into it, lung to lung, pleased when the little vessel expanded. And then, as I keep on looking, the contours don’t look like contours any more but ribs, and the bowl of glass a tiny ribcage.

I have these thoughts because of the babies. Everything in the last nine months has been about the babies. They get into and under everything. They aren’t even born and they can make you frightened, they can make Mum cry, they can make me see things that aren’t there under shifting glass. Because, all of a sudden, I think I can see something beneath the surface of the glass after all.

Something and nothing.

I do make things up. Si says, “You are certainly not a scientist, Jessica. Scientists look at the evidence and then they come to a view.” But it’s not just Si, it’s Gran and even Mum. They say I make things up. I see things that aren’t there. And hear them sometimes too. Like now, beneath the glass, through the glass.

Some movement, a blink, a sigh. A song. Some sadness.

The sensation of life, of a ribcage, breathing.

“Jessica!” That’s a shout, a real-world shout. Gran is shouting. “Jessica, Jess!”

I jolt out of myself. “What?”

“The phone, Jess.”

Gran is standing at the bottom of the stairs, the phone in her hand.

It has come. The message. She knows. She knows about the babies.

I abandon everything, fly down the stairs, rip the phone from her.

“Yes?”

It is Si.

“Jess,” he says. “Jess.”

“Yes!”

“They’re alive. They’re alive, Jess.” His voice doesn’t sound like his normal voice, it sounds floating. I conjure his face. His eyes are full of stars.

I know I’m supposed to say something , but I don’t know what.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” says Gran.

“And they both have a heart,” says Si. “Two hearts, Jess. One heart each.”

Then I find something to say.

“Omphalopagus,” I say.

Omphalopagus is the technical term for babies joined at the lower chest. These type of babies never share a heart, so I don’t know why Si is so surprised. After all, it was Si who did the research, hours and hours of it on the net. Si who taught me the word, made me pronounce it back to him. Omphalo – umbilicus. Pagus – fastened, fixed. Fixed at the navel. The twins umbilically joined to each other and to Mum and right back through history to the Greeks who coined the word in the first place.

Me and the joins.

Si and the statistics.

Si’s endless statistics. Seventy per cent of conjoined twins are girls. Thirty-nine per cent are stillborn. Thirty-four per cent don’t make it through the first day of life.

Si’s eyes, shining.

“Can you give me back to Gran now, Jess,” says Si.

As I hand over the phone, I remember the night of Mum’s nineteen-week scan. I’d come down for a raid on the cereal cupboard. Si and Mum were talking in the sitting room, hushed, serious talk.

“They’re gifts of God,” I heard Mum say.

I stood at the door of the kitchen waiting for Si to put Mum right about that. I waited for him to tell Mum what he’d told me earlier that afternoon that, despite a great deal of mystical mumbo jumbo talked about conjoined twins down the ages, they are actually just biological lapses, slips of nature. Embryos that begin to divide into identical twins, but never complete the process, or split embryos that somehow fuse back together again. A small error, a malfunction, nothing to be surprised about, considering the cellular complexity of a human being.

I wait for him to say this. But he doesn’t.

“They’re miracles,” Mum says. “Our miracles. And I don’t care what anyone says. They’re here to stay.”

And Si doesn’t go on to mention the thirty-nine per cent of conjoined twins who don’t make it through the birth canal, or the thirty-four per cent who die on day one.

He just takes her in his arms and lets her bury her head in his chest. I see them joined there. Head to chest.

I’ve only been gone from my bedroom a matter of minutes, but it feels like a lifetime. Even the room doesn’t look the way it did before. It’s bigger, brighter, there is sunlight splashing through the window.

“The babies,” I shout. “They’re alive!” I jump on the bed and throw myself into a wild version of a tribal dance Zoe once taught me. Then I catch sight of myself in the mirror and stop. Immediately.

I also see, in the mirror, the flask. It has fallen over, it’s lying on its side on the desk.

No. No!

I scoot off the bed.

Please don’t be cracked, please don’t be broken.

The flask has only just entered my life and yet, I realise suddenly, I feel very powerfully about it. Connected, even. I find myself lurching forwards, grabbing for it. But it isn’t my beautiful, breathing flask, it is just a bottle. Something you might dig up in any old back garden. It isn’t broken, but it might just as well be, because the colours are gone and so are the patterns. No, that’s not true, there are whorls on the surface of the glass still, but they aren’t moving any more, and the bubbles, my little seed fish, they aren’t swimming. And there is nothing – nothing – inside.

I feel a kind of fury, as though somebody has given me something very precious and then just snatched it away again. I realise I already had plans for that flask. I was going to remove the cork and…

The cork – where is the cork?

It isn’t in the bottle. I scan the desk. It isn’t on the desk. But how can it be anywhere but in the bottle or on the desk? Did I imagine a cork? No, I saw it: a hard, discoloured thing, lodged in the throat of the flask. I look into the empty bottle, as if the cork might just miraculously appear. But it doesn’t. The smell of the bottle is of cold and dust. There can’t have been anything in that bottle.

And yet there was.

There was something crouched inside that glass, waiting.

No, not crouched, that makes it sound like an animal. And the thing didn’t have that sort of form, it was just something moving, stirring. Then I see it, the cork. Look! There on the floor. It’s not close to the flask, not just fallen out and lying on the desk, but a full metre away. Maybe more. To carry the cork that far something big, something powerful, must have come out of the flask, burst from it.

So where is that thing now?

It’s on the window sill.

What I thought was a patch of sunlight isn’t sunlight at all. It’s bright like sunlight, but it doesn’t fall right, doesn’t cast the right shadows. Light coming through a windowpane starts at the sun and travels for millions of miles in dead straight lines. You learn that in year 6. Light from the sun is not curved, or lit from inside, or suddenly iridescent as a soap bubble or milky as a pearl. It doesn’t expand and pulse and move. It doesn’t breathe. Whatever is on the window sill, it isn’t light from the sun.

I go towards it. It would be a lie to say I’m not frightened. I am frightened, terrified even, but I’m also drawn. I can’t help myself. I remember my old maths teacher, Mr Brand, breaking off from equations one day and going to stand at the window where there was a slanted sunbeam. He cupped his hands in the beam and looked at the light he held – and didn’t hold.

“You can’t have it,” he said. “You can’t ever have it.”

And all of the class laughed at him. Except me. I knew what he meant because I’ve tried to capture sunbeams too.

And now I want the thing on the window sill, because it is strange and beautiful and I don’t want to lose it again. I don’t want to feel what I felt when I saw that the flask was empty, which is sick and hollow, my stomach clutching just like in the moment when Mum told me Aunt Edie was dead.

So I move very slowly and quietly, as though the thing is an animal after all and might take fright. And it does seem to be vibrating – or trembling, I can’t tell which – as though it is aware of me, watching me, though something without eyes cannot watch.

“It’s all right,” I find myself saying. “It’s all right. I won’t hurt you.”

I won’t hurt it! What about it hurting me?

My room’s not big, as I’ve said, but it takes an age to cross. I am just a hand-stretch away from the pearly, pulsing light when there is a sudden whoosh, like a wind got up from nowhere, and I feel a rush and panic, but I don’t know if it is my rush and panic or that of the thing which seems to whip and curl past my head and pour itself back into the flask.

Back into the flask!

Quick as a flash, I put my thumb over the opening and I hold it down tight as I scrabble in the desk for my sticky tape. I pull at the tape, bite some off, jam it over the open throat of the flask and then wind it again and again around the neck, so the thing cannot escape.

I have it captured.

Captured!

Then I feel like one of those boys you read about in books that pull the wings off flies: violent, cruel. But here’s the question: if you had something in your bedroom that flew and breathed and didn’t obey the laws of science, would you want it at liberty?

There you are then.

When my heart calms down, I feel I owe the flask (or the thing inside it) an explanation. I think I should tell the truth, about the fear as well as the excitement. But I don’t know who or what I’m dealing with, so I also feel I shouldn’t give too much away. I should be cautious. Si’s always saying that: a man of science proceeds with care. Or If you’re going to mix chemicals, Jess, put your goggles on.

I’m not sure what sort of goggles I need to deal with the thing in the flask, but I think the least I can try is an apology.

“I’m sorry about the sticky tape,” I say.

I’m not really expecting a reply and I don’t get one, but the movement inside the flask does seem to become a little less frantic, so I have the feeling the thing is listening.

“I guess you must have been in that flask a long time,” I say next.

Where does that remark come from? From the cold and the dust I smelt in the bottle? Or from some story-book knowledge of things in bottles, genies in lamps? What am I imagining, that the thing is some trapped spirit cursed to remain in the flask for a thousand years until – until what? Until Jessica Walton arrives with her father’s ill-fitting slide rule? They say (correction: Si says) if you put a sane person in a lunatic asylum for any length of time they become as mad as the inmates. Me? I’m talking to a thing in a flask.

I’m calling it you.

The word you implies that the thing I’m talking to is alive. I mean you don’t say you to a box of tissues, do you? Or to a hairbrush or a necklace or a mobile phone. So I am making a definite assumption about the thing being alive. Mr Pugh, our biology teacher, says that only things that carry out all seven of the life processes can be said to be alive. Pug calls this Mrs Nerg.

M – for movement

R – for reproduction

S – for sensitivity

N – for nutrition

E – for excretion

R – for respiration

G – for growth

I look at the thing in the flask. Movement – no doubt about that. Reproduction. I’m not sure I want to think about that right now. Sensitivity. Definitely. It’s sensitive to me, I’m sensitive to it. Nutrition. Does the thing eat? Unlikely. It doesn’t have a mouth. But then plants eat and they don’t have mouths. Excretion. Not important. If you don’t eat you don’t need to excrete. Respiration. Yes, it breathes, doesn’t it? And it has to get energy from somewhere or it couldn’t move and it certainly moves. Growth. Yes again; I think I can imagine it growing.

To be alive, Pug says, you have to be able to carry out all seven of the processes. Not two, or five or one. All seven.

I think Pug may have missed out on some of his training. This thing is definitely alive.

“Who are you?” I say. “What are you?”

The thing does not respond.

I retreat a bit. “I think you’ll be safer in the flask for a while,” I say.

I mean, of course, that I’ll feel safer if the thing is in the flask. I’ve heard adults do this. They tell you something they want by making it sound useful to you, like, You’ll be much warmer in your coat, won’t you?

“Because,” I add, “I have to go to the hospital in a minute. Gran’s taking me to the hospital.”

No reply.

“To see the babies.”

No reply.

“So I’m just going to pop you (you) back in the desk for a bit.”

No reply.

“OK?”

“You see, I noticed how you rushed back in the flask yourself, so it must be your home, I guess. Am I right?”

No reply.

“My name’s Jess, by the way.”

Some little silver seed fish, swimming.

“How do you do that? How do you make the fish swim?”

No reply.

“It’s beautiful.”

No reply.

“So just wait, OK?”

No reply.

“Promise?”

Very gently, I place the flask back into the dark space behind the left-hand drawer in the desk.

“See you later,” I say, as I leave the room.

Our local hospital is too small to deal with cases like the twins’, so we have to go to the city. It’s a long drive.

“Your mum will be very tired, you know that, don’t you?” Gran says.

She makes it sound like we shouldn’t be going, but I know why we’re going. In case the twins belong in the thirty-four per cent who die on day one.

The Special Care Baby Unit is in the tower-block part of the hospital, on the fifteenth floor. We come out of the lift to face a message to tell us we are In the Zone and to make sure we scrub ourselves with the Hygienic Hand Rub. The doors to the unit are locked and we have to ring to gain admission.

Si hears us as we check in at the nurses’ station and comes out to greet us.

“Angela,” he says to Gran and then, “Jess.” And he puts his hand out to touch me, which he doesn’t usually. I look at his eyes. They aren’t sparkling, but they are smiling. “Come on in.”

There are four incubators in the room and five nurses. Two of the nurses are wearing flimsy pink disposable aprons and throwing things into bins. There’s an air of serious hush, broken only by the steady blip of ventilators. Beside each cot is a screen with wavy lines of electronic blue, green and yellow. I don’t know what they measure, but they’re the sort of machines you see in films that go into a single flat line when people die. Mum is not sitting or standing, but lying on a bed. They must have wheeled her in on that bed, and braked her up next to the twins. She doesn’t look up immediately when we come into the room; all her focus, all her attention is on my brothers.

Brothers.

All through the pregnancy, Mum’s been calling them my brothers. When the twins are born, when your brothers are born… But, I realise, standing in the hospital Special Care Unit, that they are not my brothers. Not full brothers, anyway. We share a mother, but not a father, so they are my half-brothers. But half-brothers sounds as if they’re only half here or as if they don’t quite belong. And that’s scary. Or maybe it’s actually me that doesn’t quite belong any more, as though a chunk of what I thought of as family has somehow slid away. And that’s even scarier.

So, I’m going to call them brothers – my brothers.

Mum looks up, shifts herself up on her pillows a little when she sees me, although I can see it hurts her.

“Jess… come here, love.”

I come and she puts her arms right around me, even though it’s difficult with leaning from the bed.

“Look.” She nods towards the incubator. “Here they are, here they are at last.”

They lie facing each other, little white knitted hats on their heads, hands entwined. Yes, they’re holding hands. Fast asleep and tucked in under a single white blanket they look innocent. Normal.

“Aren’t they beautiful?” says Mum.

“Yes,” I say. And it’s true, though there is something frail about them, two little birds who can’t fly and are lucky to have fallen together in such a nest.

“You were a beautiful baby too, Jess.”

She is making it ordinary, but it isn’t ordinary. Somewhere beneath that blanket, my brothers are joined together and I want to see that join. At least I do now, although for months the idea of the join has been making me feel queasy.

There, I’ve said it.

The truth is, when Mum first told me she was pregnant I felt all rushing and hot. Not about the join, which we didn’t know about then, or even about them being twins. No, I felt rushing and hot about her being pregnant at all. I can’t really explain it except to say I didn’t want people looking at my mother, I didn’t want them watching her swelling up with Si’s baby. It seemed to be making something very private go very public. And I didn’t like myself for the way I felt, so when it turned out to be twins, and conjoined twins at that, I hid myself in the join. I made this the secret. I didn’t want people to know about the join (I told Zoe, I told Em), because of all the mumbo jumbo talked about such twins down the centuries. I didn’t tell them that I wasn’t so sure about the babies myself, that the idea of the join actually made me feel sick to my stomach. I kept very quiet about that.

Am I a bad person?

A nurse is hovering and sees the babies stir.

“Do you want to hold them, Mum?” the nurse says as if my mother is her mother.

“Yes,” says Mum.

Si helps Mum into a comfortable sitting position while the nurse unhitches one side of the incubator and adjusts some tubes. Then he stands protectively as the nurse puts a broad arm under both babies and draws them out. Si never takes his eyes off the babies and there is something fierce in his gaze and something soft too, that I’ve never seen before.

“There now,” says the nurse as she gives the babies to Mum. They are in Mum’s arms, but they are still facing each other, of course. The nurse has been careful to keep the blanket round the babies as she lifts them and she’s careful now to tuck it in.

One of the babies makes a little yelping noise and Mum puts a finger to the baby’s lips and he appears to suck.

“They’re doing very well,” says Mum, and then she loosens the blanket.

The babies are naked, naked except for two outsized nappies which seem to go from their knees to their waists – where the join begins. Mum leaves the blanket open quite deliberately. Gran turns her head away, but I look. I look long and hard as Mum means me to do.

The babies’ skin is a kind of brick colour, as if their blood is very close to the surface, and it is also dry and wrinkled, as if they are very old rather than very young. Aunt Edie again. But the skin where they join is smooth and actually rather beautiful, like the webs between your fingers. It makes me feel like crying.

Very gently, Mum strokes the place where her children join, and then she draws the blanket back around them.

I realise then I don’t know what the babies are called.

“Richie,” says Mum, “after Si’s father. And Clem, after mine.”

It seems to be enough for Mum. She lies back and closes her eyes and the nurse comes and takes the babies away again. I think Si would like to lift them himself, but he doesn’t dare. Maybe he feels they are too fragile, that he’d hurt them.

Mum seems to have gone into an almost immediate sleep, and just for a moment, I feel we might all be just some dream of hers – me and Si and Gran and the babies all rather unlikely conjurings of her exhausted brain. And then, as I watch her chest rise and fall, I think about the flask and that seems like an even deeper dream. I had been going to tell Mum about the flask, how I found it in the desk and how it was full of something unearthly, something beautiful and scary at the same time and how I captured it, because I feel fierce and soft towards it, just like Si does towards the twins, but that I also feel bad because, as Mr Brand says, you can’t catch things that are supposed to be wild and free and…

“I think we ought to go now,” says Gran.

“Mum…” I say.

“Ssh,” says Si. “She needs to rest.”

By the time we get back home it is almost dark.

“Who’s that?” Gran asks as we turn into our drive.

It’s Zoe, of course, knocking at our front door. She turns as she hears the car pull up. I wind down my window.

“Want to come to the park?” she asks.

Zoe and I often go to the park at dusk. It’s one of our little rituals. We swing on the swings after all the little kids have gone home. We swing and talk. Or Zoe dances. She dances around the swan on its large metal spring. She dances along the wooden logs which are held up by chains, she backflips off the slide. When she’s tired, which isn’t often, we lie together on our backs in the half-moon swing and look at the sky. Or I look at the sky anyway. She looks upwards, but what she sees I don’t know, because people can look in the same place but not see the same things, can’t they?