Полная версия

Sea Room

The wind was coming and going around me. I called the Coastguard on the VHF, Channel 16. ‘Stornoway Coastguard, Stornoway Coastguard, this is Freyja, Freyja, Freyja.’ My eyes were on the sea ahead for the white on Damhag, the appearance of a Galta, the radio in its waterproof case in one hand, the tiller in the other communicating the quiver of the sea to my hand. Out of the radio a voice:

‘Freyja, Freyja, Freyja, this is Stornoway Coastguard, Stornoway Coastguard.’ A young woman in a calm, warm office twenty miles away, grey carpet on the floor, magnetic charts of the Sea Area Hebrides covering half of one wall, men and women in their blue uniforms at the desks, coffee there on plastic coasters, a normal call on a normal day.

She gave me the forecast but we exchanged no names. She was the Coastguard, I was Freyja. She was providing a service. I was on my own. The weather would stay as steady as it was for the next twenty-four hours, south, southwesterly, four to five, with the wind dropping away after that. There would be something like calm for a day or two.

I was cold. I reached down into the bag at my feet for my own coffee in the thermos. My hands fumbled with it. Sandwiches in the plastic bag. I checked my position on the GPS again. It all feels a little absurd, to think that I might ever reach the condition in which it would be natural to call those rocks ‘The Gables’. I am in my own world of bags from the Stornoway Co-op, the VHF in its ‘Aquapac’, the GPS locating me through the American military satellites orbiting above. They tell me that I have passed Damhag and the Galtas. It is time to turn east.

It’s a relief. I must be nearly there. Simply taking the stern of the boat through the wind and gybing, moving the sail over to the other side, it feels better. That is a sign of arrival, or at least of near-arrival. I have got that amount of sea under my belt. All that strange width of sea has now, oddly, changed in my mind. Uncrossed, it felt terrifying. Having crossed it, I feel as if I could cross it any number of times. I sense John MacAulay at my shoulder. Is this all right John? ‘Yes,’ he says, ‘you’re not doing too badly.’

Now, though, I was moving into the shadow of the known, the sea around the Shiants. Because the Shiants are themselves such a disturbance to the flow of the tide, for others this would seem like the most hazardous and hostile section of the passage. But I’m familiar with the sea here. It is like knowing an old ill-tempered dog. I know how to get round him. Moving across the swell, a different pattern, Freyja was making a rolling barrel along the crests and then slewing into the troughs behind them. Looking up, back in the stern, with the boat underway, I saw that things would be all right. The sky was lifting. From a satellite, I would have seen the shifting of an eddy, the slight revolution of some huge cloud crozier turning on the scale of Europe, the planetary mixing of Arctic and tropical air. This was the southeastern limb of a giant depression rolling in out of the Atlantic and on to Scandinavia. It had blown me here. I felt a little sick but I could see where I was and it was where I had hoped to be. The seas breaking on Damhag were a mile to the south-east, that silent flinging of spray into the air above the rock, like a hand repeatedly flicking out its fingers, signalling ‘Keep away, keep away!’ I was well clear of it. The broken line of the Galtas extended for a mile beyond the rock, black and bitter, the knobbled spine of a half-submerged creature: one like an old woman with a bonnet, called Bodach, or Old Man; others blocky, fretted.

Beyond them, arrival, emergence, home. Coming out of the mist, draped with cloud ribbons like feather boas across their shoulders, were the islands, my islands, my destination. The Shiants are the familiar country, the place around whose shores I feel safe. Even in all its masculine severity, I know where the tide rips and bubbles, exactly where the rocks are, and the known, however harsh, is the safe and the good. Even though the sea now was more uncomfortable than anywhere on the journey, I started to feel easy. A small wave slopped aboard and I pumped it out. A shearwater cut past me and the birds were hanging around the Galtas like bees. But the relief, as ever, was ambivalent. It’s always like this. I never quite feel the comfort of arrival that I expect. It is enigmatic. This is the longed-for place, but it is so indifferent to my presence, so careless of my existence, that I might as well not have been here.

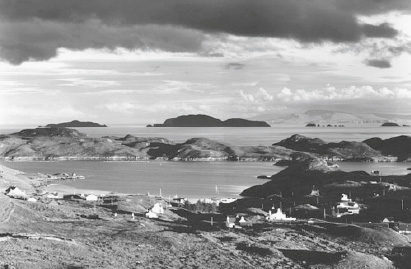

A remembered room is never as big as you think, but the Shiants always emerge much larger than I have remembered them. They are called na h-Eileanan Mora in Gaelic, which perhaps means ‘the Big Islands’, and here, now, they slowly billowed above me, a new world. They expand into reality, growing out of the mist, and their big, green, wrinkled forms drifted at me like half-inflated balloons. I let out the breath I had been holding in for hours. A home-coming to a place that provides no welcome. They come at you one by one. First Garbh Eilean, the Rough Island (garbh is the adjective you would use to describe someone who was strong, stocky, ‘a big lad’), the most masculine and the westernmost. Freyja pushed steadily eastwards, along its northern cliffs, a mile-long wall of black columned rock, slightly higher in the centre, dropping at each side, each of the columns eight or ten feet wide, bending slightly as they rise from the sea, like a stand of bamboos swayed in a breeze. The sea sucks and draws in the caves and hollows and the birds are spattered across them like paint flicked from a brush. Freyja keeps to her line without my hand on the tiller. In the lee of the cliffs, their ribbed surfaces are like the ripples of an enormous curtain, gathered in its folds; or a vast black shell.

A scallop boat skipper waves to me as my sail snaps from one side to another in the gusts off the islands. The Shiants are stretching their arms around me. Around the corner comes Eilean Mhuire, Mary Island, the sweetest, the softest, the lowest, the most feminine and the most fertile. It is early in the year and the grass has yet to grow. The islands’ skin is pale, a musty green. The sea is a little quieter here, protected by the islands from the swell. I am still a little dazed from the journey, as if I have emerged into the quiet from a room filled with noise. I slide along and remember the past.

At last, I turn into the bay which the three islands encircle. Eilean an Tighe, House Island appears, enclosing it to the south, the third of the three. Together they have always seemed to me like a family: Garbh the father, Mhuire the mother and this most domestic of the islands as their child, taking some of its character from each. The wind is less here but fluky. I let go of the tiller and the boat sails wherever it will as I tidy things away. I have crossed a sea which I have spent my life looking at: sixteen miles in three and a half hours, about four and a half miles an hour. I look back at it. There is no way I would set out on it now. Long, grey-faced waves come on at me from the south-west. For a moment I have a companion. A kittiwake, one of the smallest of the gulls, hangs buoyed above me. The way is still on the boat, making its easy last strides into the ring of islands. There is calm water in their shelter, and as if suspended above us the kittiwake comes to a point just beyond the stern, bobbing above me, curious, its arched wings like the curve of the sail, peering down from mast height into the boat, looking at me and all my possessions in their waterproof bags. Kittiwakes often hang after fishing boats, waiting for the offal as the fish are gutted. That is all it was, a hungry bird in pursuit of food, and it was only for a moment or two, but I took it as a sign of arrival.

The boat ran on into the bay. If the word ‘here’ has any meaning beyond simply the label of a place where you happen to be; if ‘here’ can be the name for the place to which you belong for more than just a moment, then this was my here. I let the anchor go and the chain ran out through the fairlead and down into the patch of sand, just off the Garbh Eilean screes where men have always anchored in a southwesterly. I unstepped the mast and folded the sail into its bag. I had arrived. I could hear the wind on the far side of the island beating without thought on the shore.

3

‘THE SEA WANTS TO BE VISITED’, a Gaelic proverb says and, as scarcely needs to be added, the host will murder its guests. Nothing can be understood about these islands, about the life that has been lived on them, and about the tensions under which people have existed here, without grasping that dual fact. The sea invites and the sea destroys. It is often said that the Hebrideans are not as natural seamen as the islanders in Orkney or Shetland, and that the northerners were fishermen who occasionally farmed and the Hebrideans farmers who occasionally fished. That isn’t entirely true, particularly in Lochs. In 1796, there were three hundred and sixty-six families. The ability of the ground itself to sustain the people was minimal. They were lucky if for every oat or grain of barley sown, they could harvest three or four.

Before the nineteenth-century Clearances, when the inhabitants of twenty-seven townships in Pairc were evicted, about three hundred of those Lochs families, distributed like limpets around the shore in their tiny hamlets, were dependent on fishing, mostly of cod and ling which were at their best between February and May. There were seventy fishing boats in Lochs, each with a crew of three or four. The Shiants would probably have had a single boat, or at most two, shared between the five families that lived here. The boats were, essentially, the same as my Freyja, although a little longer, twenty rather than sixteen feet, undecked, with six or eight oars, a heavy dipping lug rig and a hull made of pine (or larch for the better quality) on oak frames. The timber would have been imported, as it was for Freyja, from the mainland.

They can be horribly dangerous in a rising sea, when large volumes of water can land inboard without warning, and I know what would happen if a sea ever came into Freyja. Beside me in the stern I have a large bucket and I would start baling with that. I have watched myself in these situations: a kind of cold panic grips me, a terse rejection of terror. Of course it wouldn’t be enough. With the boat half full, Freyja would be riding lower than before. Almost certainly the next wave or the one after that would come in too. There would be no chance of keeping it out. The stern which John MacAulay had made for me, with that little sprung lift to its line, would not have the buoyancy. Within a minute or two the boat would be awash and there’s no baling then. That’s why the fishermen on Scalpay always ask me if I am going alone, why I am not taking anyone with me. Donald MacSween asks me every time: he smiles with the question, but not with his eyes. They say, ‘You don’t know what it will be like out there if something goes wrong. You would be safer with two.’ I know he thinks that, but he has never once said it.

I have seen one of these boats sunk before, in the warm, still conditions of a quiet bay in the Hebrides. It had been out of the water for a while, the wood had shrunk and when it was launched, the sea poured in like miniature Niagaras between the strakes on either side, rippling down step by step into a widening pool in the bilges. In half an hour she was down to her gunwales. I watched entranced as she went under. It was a blessing, not a catastrophe. I could feel the wood absorbing the water and it was like giving a thirsty animal a drink, a gulping at the longed-for element. The boat looked buried in the sea that morning. She no longer had an existence independent of the water, but sat there still and submerged as if in jelly, an embalming of her life, neither sinking nor floating but absorbed by the water from which she was usually so distinct.

That is a picture you see all around the Hebrides in the early spring, as men who have kept their boats ashore in the winter sink them for a week or so before the summer fishing. Each is tethered to its mooring in the loch like a cow in her paddock. She is happy there ingesting the goodness around her. The season of fatness is to hand and her belly is filling. It is an image of contentment but it is also a prefiguring of something worse: what happens to these small open boats when caught out in the wrong weather. They do not sink but they fill. The sea invades them. All weight in the boat must be thrown out if it is not to pull the hull down. I kept a knife beside me in the stern, ready to cut the rope which was holding down my belongings amidships so that once the hull filled I too could throw everything away. The sea, Donald MacSween told me, would soon turn the boat over and your only chance of survival was to hold onto that upturned hull. It is not easy. The little ledges formed by one strake overlapping the next do provide the thinnest of rock climbers’ footholds but the underwater profile is coated in the deliberately slimy Stockholm tar. As the weather worsens and the cold loosens your grip, the next big wave will wash you off into the sea. Then you are lost.

Records of boat losses are thin before 1800 but the nineteenth century in Lewis and Harris records again and again the loss of these boats and the drowning of their men. In February 1836, two boats from Point were caught out in a sudden gale. They were forced south before the wind, running for the Lochs coast at Cromore, just north of the Shiants. The crew of one boat survived. In the other, the four young men, inexperienced and perhaps underdressed, died of cold. Township after township lost their men. Year after year, boats went down from Barvas, Skigersta, in the district of Ness. In 1875 an oar was all that was found of a boat from Borve, coming ashore at Bragar. Two years later, a Bernera boat was lost with all its crew off the Flannans. Between 1862 and 1889, seventy fishermen from the district of Ness were drowned, in 1895, nineteen men from Back. Almost three hundred Lewis men were drowned in the second half of the nineteenth century, all of them within a few miles of their home shores, some of them watched by their families and friends as the small boats struggled to get home through the surf.

If the bodies came ashore, which they often didn’t, they, like the boats, were smashed into pieces or rotted beyond recognition. It was the pattern all down the western seaboard of the British Isles. Poor soils drive men to boats in which they drown.

At the Shiants themselves, in the spring of 1881 four young fishermen from the village of Lemreway in Lochs came out to the islands to catch a few puffins. None of them was more than twenty years old: Murdo Macmillan, Norman’s son; John Macinnes, Donald’s son; Angus Ferguson, Murdo’s son, and Donald Macdonald, Kenneth’s son. That’s how Dan Macleod, a retired merchant seaman, weaver, story-teller and the carrier of memories and traditions in Lemreway, described them to me. He tells the story in the way Hughie MacSween does, twisting his roll-up between his fingers, looking away to draw on the memory, looking at you to communicate it. Dan also gave me their addresses: the Macmillans lived at 1 Lemreway, the Fergusons at 3 Lemreway, the Macinneses at 5, the Macdonalds at 7. None of the boys was married. ‘They were young boys,’ Dan says. ‘And they wouldn’t be salting the puffins. They’d be giving them away.’

For several decades, probably since the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Lemreway men had come out to the Shiants in May and June to catch the puffins. In the 1850s, Osgood Mackenzie, then still a boy, but in time the creator of the subtropical gardens on his inherited estate at Inverewe, near Gairloch, on the mainland, came out to the Shiants and witnessed the Lemreway men catching the puffins: ‘They brought back boatloads of them because they valued the feathers,’ he wrote in his autobiography.

They also enjoyed big pots of boiled puffins for their dinners as a welcome change from the usual fish diet. They told us how they slaughter the puffins. They choose a day when there is a strong breeze blowing against the steep braes where the puffin breed, and the lads then lie on their backs on these nearly perpendicular slopes holding the butt-ends of their fishing rods. These stiff rods would be about nine or ten feet long [and almost certainly at this time made of bamboo]. Holding them with both hands, they whack at the puffins as they fly past them quite low in their tens of thousands, and whether the puffin is killed outright or only stunned he rolls down the hill and tumbles on the shore or into the sea, where the rest of the crew are kept busily employed, gathering them into the boat.

It is possible to reconstruct something of the conditions in May 1881. The steep braes to which Mackenzie refers are on the north face of Garbh Eilean, a big, green, grassy bank, the grass itself thickly enriched by the generations of puffin droppings that have fallen on it. You cannot spend five minutes there without being spattered yourself. The puffin bank faces the small rocky inlet called simply Bagh, the Bay, and beyond it the Stream of the Blue Men and the square outline of Kebock Head in Lewis. A strong breeze blowing on to them, creating the conditions the fowlers preferred, would have been a northerly. That would also be the wind that would carry the boys easily down southwards from Lemreway to the Shiants. With an ebb tide under them, it would scarcely take more than an hour to run down the six miles or so.

You can imagine the dream of the day. The colours which drain out of the Hebrides in the winter, leaving the black rock and grey turf as a monochrome ghost of the summer life, have now begun to return. The lichen glows yellow on the rocks. The off-lying skerries are pink with the thrift in flower. Fat red and white campions make cushions in the nicks of the cliffs. The sea is silk, patterned in the Stream of the Blue Men with the twisted curls and table-top bubbles of the upwelling sea.

It would have been the same in the 1850s and the 1880s as it is today: that glowing light, the notched outline of the mainland to the east hazed by the rising sun, the hills of Skye still wrapped in the morning clouds, the long broken back of the Hebrides running down to south Harris, the Uists and to Barra, and the Shiants hanging in the middle distance, a secret world, asking to be visited.

The Lemreway boys in 1881 planned to stay overnight on the islands. There was a shepherd and his family living there at the time. Donald Campbell, better known as Domhnall nan Eilean, or Donald of the Islands, had come over from Molinginish, a small township on the coast of Harris near the mouth of Loch Seaforth, twenty years before. He had his wife and children with him and together they lived in a good house of two rooms on the island, which had previously been called Eilean na Cille, the Island of the Church, but which they called Eilean an Tighe, House Island, the name it has today.

Summer was the time for visiting. Winters for the Campbells would have been lonely, but come April and May, with the stilling of the sea, the network of connections that have always bound the summer Shiants to the neighbouring islands, would re-emerge. Campbell’s employer, the farmer and Stornoway merchant, Roderick Martin of Orinsay, would bring out to him the meal and other supplies he needed. The socks which the Campbell girls had knitted over the winter would be sold or even given to anyone visiting. Gentlemen in yachts might arrive to investigate the geology or the birds. There were plenty of diversions.

The fowlers, as a courtesy as much as anything else, would have taken their boat to the anchorage just in front of the shepherd’s house on the west side of Eilean an Tighe. Courtesy and hospitality remain the norm here. Even nowadays, when a stranger arrives and the shepherds happen to be there, the greetings are warm, welcoming and generous, far more than among English people in the same situation. ‘Hallo, hallo, hallo, hallo, hallo, hallo,’ I heard Donald ‘Nona’ Smith, one of the modern shepherds, say to a man landing on the beach here one day, a rising chorus of delighted welcome.

‘Do you know him well?’ I asked Nona later.

‘No, I’ve never met him before,’ he said. ‘But you’ve got to be diplomatic.’ There is no sense of anyone’s isolation being invaded. Sociability has always included the Shiants. But it can only be presumed on to a certain extent. The Lemreway boys brought their own provisions with them, some oatmeal and perhaps some of the cod or ling they might have caught on the way down.

There is a patch of sandy grey mud on the sea-bed a hundred yards or so offshore in front of the house, and in a northerly it is protected from the worst of the sea. A cairn high on the hill may well be a mark of this anchorage. Its stones are hairy with a long-bearded lichen, and because lichen takes a long time to grow, that alone is a mark of its age. Although people are always ready to attribute seamarks in the Hebrides to the Norse, there is no real way of dating them. The boys would have dropped anchor, unstepped the mast, furled the sail and would have come ashore in their dinghy to the beach next to the Campbells’ house.

The time of birds is the time of abundance, the season of summer-time adventure but the expedition to the Shiants of the Lemreway boys ended in disaster. Their boat, ‘an Orkney-type boat, a double ender, a stout boat’, Dan Macleod calls it, eighteen feet in the keel, a little longer than Freyja, had been safe enough overnight, protected from the northerlies by the bulk of Garbh Eilean. It can be quite still in there even on a wild day. While you hear the groaning of the breakers on the other side a mile away, plunging their long tongues into the caves at the cliff foot and exploding inside them – a heavy, quarryman’s boom reverberating through the island, at your feet, in the lee of the vast, whale body of Garbh Eilean, the water laps on the rocks and the eiders paddle from one inlet to another as if asking for bread in St James’s Park.

The boys spent the night with the Campbells and were due to return home the following day – it was a Wednesday – but they never arrived. That evening, as Dan Macleod has written,

their families, neighbours and friends gathered around scattered vantage points anxiously scanning the surface of the water to see if they could detect any sign of their loved ones’ boat coming home. Alas, there was none and the young men’s fathers resolved to sail out to the Shiants at first light the following day.

The party of fathers arrived at the shepherd’s cottage, and Domhnall nan Eilean told them that the boys had stayed with him on the Tuesday night but when the wind changed direction on Wednesday morning, they had decided to move the boat to a more sheltered spot.

The wind had gone round to the south-west and stiffened. In that wind the anchorage off the house was the most exposed place on the Shiants and there was no way they could leave it there. In a southwesterly, the only usable place is in the shadow of the giant boulder screes that run along the eastern side of Garbh Eilean. Looking down from the cliff-top there on a sunny day, at low tide, with the light driving down through the twenty feet or so of water, in which the puffins and the other auks dive and dart for food, you can see the pale turquoise patch of sand into which boats can drop their anchor. All around are boulders, in which an anchor would get caught and could never be retrieved; or cobbles, through which the anchor would slither in a wind. That sandy patch is well tucked in, sheltered from the west by the block of land above it, and sheltered from the north by a narrow arm of the island which stretches out eastwards towards Eilean Mhuire.