Полная версия

Sea Room

A gannet suddenly slaps into the sea beside me. No warning. I start at it and remember this, the story of one of the stewards of St Kilda. At some time in the seventeenth century, (no date, because dates are rarely certain here), the steward, sailing out from Harris to his island responsibilities forty miles away across the Atlantic, found his boat passing through a shoal of herring so thick that the bodies of the fish lay like a pavement on the surface of the water. There was a silver skin to the sea and any man could have walked across it. A south wind was blowing and the boat was skimming through the bodies of the herring as if skating across them. All around them the gannets were diving, again and again, no hesitation necessary, no accuracy needed. It was the atmosphere of a tobogganing party. If the gannets had been children they would have been shrieking at the pleasure. The steward and his companions were gliding to St Kilda as if to Heaven.

A gannet, mistaking his moment, plunging for fish but ignoring the people, dived for his prey but missed his mark, his narrowed, darting body slicing down past mast, sail and shrouds, past the crew at the sheets, into the body of the open boat where its beak and head were impaled in the bottom strakes of the hull. The bird was dead on impact. Its enormous wings stretched across the frames and thwarts of the boat almost from one gunwale to another. Its perfect white body, six feet across from black wing-tip to black wing-tip, and a yard long, took up as much room as a man. The bubble of perfection had been pierced. The plank was splintered through. Twenty miles of the Atlantic separated the steward and his party from Harris and twenty from St Kilda. Could they mend the punctured hull? Would they drown here? Was water coming in faster than they could keep it out? Searching for the damage down in the bilges, the steward and his crew, scrabbling the ropes and creels out of the way, looked for signs of water bubbling in. There was none. Miraculously, the bilges were dry. The gannet’s head had plugged the hole its dive had made and its body was left there for the rest of the voyage, four hours to the bay on Hirta, with the enormous corpse beside them performing its role as feathered bung.

I was first told that story when I was a ten-year-old boy. I stood up with shock as the crisis hit and, of course, I have never forgotten it. I have learned since how prone to accident the gannet is. Every year in each of the great rocky gannetries around the Scottish coast, on Ailsa Craig and Bass Rock, in the stupendous avian city of St Kilda, hundred of gannets crash on arrival, breaking a wing or a neck, either dying then or over many weeks as their thick reservoirs of subcutaneous fat slowly wither in the breast, a pitiable death. Evolution does not create the perfect creature, only the creature that is perfect enough.

It is the one bird I wish would come to live on the Shiants. For a few years in the 1980s, the islands were the smallest gannetry in the world. Like a corporal among dukes, the Shiants made their glorious appearance in the ranks of the great: starting with St Kilda 100,100 gannets and Grassholm 60,000, the list ends with:

Shiants: 1.

He was to be seen for a few years perched solemnly on one of the north-facing rock buttresses of the islands, looking out woefully to the Lewis shore, hoping, I always imagined, that a lovely gannet girl might think this a suitable place to make her life. Around him, the guillemots stared and squabbled. Above them, the fulmars spat and cackled. No other gannet came to join him and by 1987, the Shiants, still listed in the wildly prestigious catalogue of British gannetries, now had an even more woeful entry:

Shiants: o

The mind is distracted for a moment and then returns to the foolishness of what you have done. It was not exactly the vision of the drowning man but I found myself thinking of the people I love and have loved. Do men drown regretting what they have done with their lives, all the stupidities and meannesses, the self-delusions and deceits? I was driving blind and it was not comfortable. I had been in the boat nearly three hours and even through all the layers of clothes I was getting cold. I had a hand-held GPS with me and it put my position at just about six degrees, twenty-seven minutes west, fifty-seven degrees, fifty-four minutes north. I should have been almost on the islands now but I could not see into the mist-bank to the north and east of me. I needed to come round to the north side of the Shiants to bring the boat into the bay between them, protected there from the southwesterlies. I had to overrun them and then turn for shelter. I hadn’t been here for a year and by now I was in a state of high anxiety.

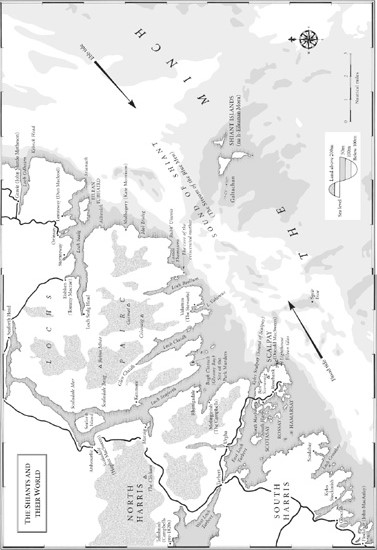

This approach is larded with danger. Lying off the islands to the west is a chain of rocks and small steeply banked islets called the Galtachan or Galtas. No one knows what their name means but it may perhaps come from the Old Norse word, Gaflt, meaning the gable-end of a house. That, at least, is John MacAulay’s suggestion. It is a derivation which even now makes me smile. So much for these savage seas! So much for the tides that rip through the narrow channels between the Galtas! When the Ordnance Survey first came here on 27 October 1851, the surveyor wrote a hurried and unpunctuated description in his notebook:

Received Name: Galltachan

Object: Islands

Description: This is a range of Several [?] High and Low water Rocks extending from east to west three of which has a little of their top covered with rough pasture and surrounded by small but steep rocky Cliffs. there is a channel between each and every one of the High Water Rocks. at a distance they appear low but are no way inviting as at all times especially at Spring tides there is a rapid current about them the tide flows exceedingly strong flowing the same as a large River.

That is the modern voice; the survey officer, Thomas O’Farrell, measuring, estimating, a little fearful, unable to disassociate his description of the place from his apprehension over it. It could easily have been my voice, frightened now of being swept by the tide into the channels between the Galtas through which the deep-drawing Freyja might not have passed. Perhaps John MacAulay would have felt relaxed here, but neither I nor O’Farrell were Vikings. Would either of us so calmly have named these rocks ‘the gable-ends’? Would we have wanted to or been able to domesticate them so casually? The Gables? It is a joke, a place with a double garage and stuck-on timbers outside Beaconsfield. To know them as the Gables is evidence of an attitude of heroic calm; a sudden jump into the Viking world. To call them that is as cool as the gannet, as easy in the sea as by the hearth, almost literally at home there. Or maybe something else: the roofs of buried houses, mansions drowning in the Minch.

Freyja does at least belong to that world. I hold her tiller and she is my link to a chain that stretches over five hundred miles and a thousand years to the coast of Norway. Because there is no timber on the Outer Hebrides, the commercial connection with the Baltic has remained alive. Until no more than a generation ago, Baltic traders brought Finnish tar, timber and pitch direct to Stornoway and Tarbert in Harris. Although Freyja’s own timber comes from the mainland of Scotland, her waterproofing below the water-line is known as ‘Stockholm tar’: a wood tar, distilled from pine and imported from the Baltic at least since the Middle Ages. Until well into the nineteenth century, kit boats in marked parts came imported from Norway to the Hebrides, travelling in the hold of merchant ships, and assembled by boat builders in any notch or loch along the Harris or Lewis coast. In 1828, Lord Teignmouth, the ex-Governor-General of India, friend of Wilberforce, came out to the Shiants in the company of Alexander Stewart, the farmer at Valamus on Pairc, who had the tenancy of the islands. They

launched forth in this gentleman’s boat, a small skiff or yawl built in Norway, long, narrow, peaked at both ends, extremely light, floating like a feather upon the water, and when properly managed, with the buoyancy and almost the security of a sea-bird on its native wave.

The British Imperialist, the liberal evangelical, member of the Clapham Sect, travels in a Viking boat on a Viking sea. I nearly called Freyja ‘Fulmar’ because of that phrase of Teignmouth’s. No bird is more different on the wing than on the nest and in flight the fulmar is the most effortless of all sea birds. It was that untroubled buoyancy in wind and water that I was after. But Freyja’s fatness was what settled it.

Almost everything in her and the world now around her, if described in modern Gaelic, would be understood by a Viking. The words used here for boats and the sea all come from Old Norse and the same descriptions have been on people’s lips for a millennium. If I say, in Gaelic, ‘windward of the sunken rock’, ‘the seaweed in the narrow creek’, ‘fasten the buoy’, ‘steer with the helm towards the shingle beach’, ‘prop the boat on an even keel’, ‘put the cod, the ling, the saithe and the coaley in the wicker basket’, ‘use the oar as a roller to launch the boat’, ‘put a wedge in the joint between the planking in the stern’, ‘set the sea chest on the frames amidships’, ‘the tide is running around the skerry’, ‘the cormorant and the gannet are above the surf’, ‘haul in the sheet’, ‘tighten the back stay’, ‘use the oar as a steerboard’, or say of a man, ‘that man is a hero, a stout man, the man who belongs at the stem of a boat’, every single one of those terms has been transmitted directly from the language which the Norse spoke into modern Gaelic. It is a kind of linguistic DNA, persistent across thirty or forty generations.

Sometimes the words have survived unchanged. Oatmeal mixed with cold water, ocean food, is stappa in Norse, stapag in Gaelic, although stapag now is made with sugar and cream. With many, there has been a little rubbing down of the forms in the millennium that they have been used. A tear in a sail is riab in Gaelic, rifa in Old Norse. The smock worn by fishermen is sguird in Gaelic, skirta in Old Norse. Sgaireag is the Gaelic for ‘seaman’, skari the Norse word. And occasionally, there is a strange and suggestive transformation. The Gaelic for a hen roost is the Norse word for a hammock. Norse for ‘strong’ becomes Gaelic for ‘fat’. The Norse word for rough ground becomes ‘peat moss’ in Gaelic. A hook or a barb turns into an antler. To creep – that mobile, subtle movement – translates into Gaelic as ‘to crouch’: more still, more rooted to the place. A water meadow in Norway, fit, becomes fidean: grass covered at high tide. ‘To drip’ becomes ‘to melt’. A Norse framework, whether of a house, a boat or a basket, becomes a Gaelic creel.

But it is the human qualities for which Gaelic borrowed the Viking words that are most intriguingly and intimately suggestive of the life lived around these seas a thousand years ago. There is a cluster of borrowings around the ideas of oddity and suspicion. Gaelic itself, if it had not taken from the invaders, would have no word for a quirk (for which it borrowed the Old Norse word meaning ‘a trap’), nor for ‘strife’, nor ‘a faint resemblance’ – the word it took was svip, the Norse for ‘glimpse’. The Gaelic for ‘lullaby’ is taladh, from the Norse tal, meaning ‘allurement’, ‘seduction’.

The vocabulary for contempt and wariness suddenly vivifies that ancient moment. Gaelic borrowed Norse revulsion wholesale. Noisy boasting, to blether, a coward, cowardice, surliness, an insult, mockery, a servant, disgust, anything shrivelled or shrunken (sgrogag from the Old Norse skrukka, an old shrimp,) a bald head, a slouch, a good-for-nothing, a dandy, a fop, a short, fat, stumpy woman (staga from stakka, the stump of a tree), a sneak (stig/stygg), a wanderer – all this was something new, and had arrived with the longships. Fear and ridicule, the uncomfortable presence of the distrusted other, the ugly cross-currents of two worlds, the broken and disturbing sea where those tides met: all this could only be expressed in the odd new language the strangers brought with them.

I was steering west of the Galtas but I had to make sure it was a long way west. The water had turned, as it does sometimes with the tide, into strange, long slicks, each slab of water as smooth as a hank of brushed hair. It is a horrible sensation in the mist, a strangeness at sea, when all you want is normality and predictability. Was this the effect of a rock ahead of me which I couldn’t see? About five hundred yards off the westernmost Galta was the most dangerous rock in the Shiants: Damhag, perhaps meaning ‘ox-rock’ in Gaelic (no one knows why) or more likely ‘a rock awash’. It is pronounced ‘Davag’. O’Farrell had heard of its terrors:

Received name: Damhag

Object: Rock

Description: This is a Small low water Rock seen only at Spring tides which makes it very dangerous to mariners, lying about 15 Chains west a Group of high and low water ones, the tide flows so Strong and rapid here that unless Mariners were aware of its Situation it would often become fatal. there has been not long ago a large vessel wrecked on it the vessel and crew were all lost. at neap tides if the wind is high there is always Breakers seen on it.

That ship was in fact the Norwegian schooner, Zarna, of Christiansund, which was wrecked here on 13 February 1847, en route to Norway from Liverpool with a cargo of salt.

None of this is pleasant in a small boat in a rising sea. If the GPS could be relied on, I was well clear but I didn’t want to overrun too far. The long slicks of water were giving way to a broken, pitted surface like the skin of an orange.

North-west of the islands is the Sound of Shiant, separating them from the bulk of Lewis five or so miles to the west. The Sound is a place of deep discomfort. I have never been in there in a small boat and the fishermen in Scalpay have warned me away from it. Donald MacSween (another Viking name, Sveinson), whom I have known since I was a boy, and who, for a few years after his cousin Hugh MacSween gave up, was the tenant of the Shiants, told me only that I had to respect the Minch. ‘Pick your day and pick where you go and you will be all right.’ After supper in Rosebank, his house in Scalpay, in the sitting room, with the coal fire burbling beside us and Rachel, his wife, looking through the packets of seeds she was to plant that spring, from time to time telling me that I was a disgrace, ‘walking around the way you do with holes in your socks the like of which I have never seen in my life’, Donald and I sat over a chart together.

He is a strict churchman, a man of immense propriety and overwhelming charm. ‘What do you talk about all the time on the radio to each other when you are out at sea?’ I asked him once. Channel 6 on the VHF is solid with Gaelic chat, day and night, between the fishermen. ‘Local talent,’ he said, with a face like a gravestone. Rachel told me that in three decades of marriage she has never once seen him angry. ‘He must be a saint then,’ I said.

‘Well, he’s a saint to me.’

Donald knows all there is to know about the Minch. Without a second thought I would trust my life to him. He has fished it since he was a boy and he knows every one of its ‘dirty corners’. ‘Oh yes,’ Mary Ann Matheson, the mother of John Murdo, the present shepherd on the Shiants, said to me once, ‘you need to listen to Donald. He knows all the crooks and crannies of the wind.’

With his glasses on and his enormous, scarred hands feeling their way across the figures and the submarine contours, he went through the chart with me. Off the mouths of Lochs Seaforth, Bhrollúm and Cleidh there are big riffles on the ebb as the lochs drain out. There is a bar across the mouths of each of them so that the draining water has to rise from something like sixty to twenty fathoms as it emerges. That does not make for an easy sea and in my boat I should avoid them.

But the real danger was in a triangle of sea between the Shiants, Rubha Bhrollúm, which is the nearest point of Pairc on Lewis, and the mouth of Loch Sealg, five miles or so to the north. I was not to enter it. The sea there was not, Donald said, ‘very pleasant’. Heavy, fast tides ebbing down from Cape Wrath or flooding up from the southern Hebrides are squeezed by the islands here into a narrower channel. At the same time, the water is forced to run over a knotted and fractured sea-bed.

A huge ridge of rock, three miles long and more than three hundred and fifty feet high, coming within seventy or eighty feet of the surface, stretches most of the way across the Sound, a sharp-edged submarine peninsula reaching out from the Shiants towards Rubh’ Uisenis on Lewis. It makes that short passage on which the Admiralty chart-markers print an innocuous-looking set of wrinkly lines, meaning ‘tidal overfalls’, the equivalent of a set of rapids in a river. But the river coming up to them is five miles wide and four hundred and fifty feet deep, that enormous mass of water running at the height of spring tides at almost three knots, the speed of a fast walk. Any idea of a river is of the wrong scale. This is the equivalent in tonnage and in volume of an entire range of hills on the move. At certain states of high wind against spring tide, the sea here can turn into a white and broken mass of water, a frothing muddle of energies stretching across the whole width of the Sound, a chaos in which there are not only steep-faced seas coming at you from all directions, but, terrifyingly, holes, pits in the surface of the sea, into which the boat can plunge nose-first and find it difficult to return.

The Sound of Shiant is also known as Sruth na Fear Gorm, the Stream of the Blue Men, or more exactly the Blue-Green Men. The adjective in Gaelic describes that dark half-colour which is the colour of deep sea water at the foot of a black cliff. These Blue-Green Men are strange, dripping, semi-human creatures who come aboard and sit alongside you in the sternsheets, sing a verse or two of a complex song and, if you are unable to continue in the same metre and with the same rhyme, sink your boat and drown your crew.

The Reverend John Gregorson Campbell, Minister of Tiree from 1861 to 1891, and a renowned collector of folklore in the Hebrides, claimed to have met a fisherman who had seen one. It was, Campbell reported, ‘a blue-coloured man, with a long, grey face and floating from the waist out of the water, following the boat in which he was for a long time, and was occasionally so near that the observer might have put his hand upon him.’

Something about the Blue Men has attracted one folklorist after another. Donald A Mackenzie, author of Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life, published in 1936, even claimed to have preserved a fragment of verse dialogue between skipper and Blue Man tossing beside him in the billows. Both had, it seems, been studying the verses of Edward Lear and the rhythms of Coromandel and the Hills of the Chankly Bore were still ringing in their ears:

Blue Chief: Man of the black cap, what do you say

As your proud ship cleaves the brine?

Skipper: My speedy ship takes the shortest way

And I’ll follow line by line.

Blue Chief: My men are eager, my men are ready

To drag you below the waves.

Skipper: My ship is speedy, my ship is steady.

If it sank it would wreck your caves.

‘Never before,’ Mackenzie wrote, ‘had the chief of the blue men been answered so aptly, so unanswerably. And so he and his kelpie brethren retired to their caverns beneath the waves of the Minch.’

Mackenzie went on to describe how ‘Once upon a time,’ – a giveaway phrase, if ever there was one, for non-first hand information – ‘a ship passing through the Stream of the Blue Men came upon a blue coloured man asleep on its waters. The sleeper for all his nimbleness was captured and taken aboard.’ The crew bound him hand and foot but were appalled to see two of his friends following. Mackenzie then reports the conversation between the pair of Blue Men: ‘One said to the other: “Duncan will be one man.” The other replied: “Farquhar will be two.”’

This was clearly a threat to the crew but luckily, before disaster could strike, the Blue Man they had captured ‘broke his ropes and over he went.’

Is there anything more serious one can say about this? TC Lethbridge, sailor, archaeologist, savant, Keeper of Anglo-Saxon Antiquities at the University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge for much of the twentieth century, who believed that Druidism and Brahmanism were the same, had an intriguing theory about the Blue Men. In The Power of the Pendulum, his final, eccentric and free-spirited book, published in 1976, he touched briefly on the survival of beliefs such as these. Making connections which more strait-laced archaeologists are wary of, he identified the Blue Men with Manannan, the Celtic sea-god remembered in the place-name of Clackmannan, meaning ‘Manannan’s stone’, and Manannan with Poseidon. The seaways around the shores of Europe bring stories, and ways of looking at the world, as well as goods. He plunged on into dangerous territory. A ditty had been recorded in the early twentieth century that was still being said or muttered among the fishermen of Mallaig:

Ickle Ockle, Blue Bockle Little youthful Blue God Fishes in the Sea. or Of the fishes of the sea If you’re looking for a lover If you’re looking for devotion Please choose me. Please choose me.It is a charm-cum-game-cum-riddle for Poseidon, of whom the Blue Men in the Minch were the last, rubbed-down remnants. ‘How would you describe a god of this kind?’ Lethbridge asked. ‘As a cloud of past memories, to some extent animated by the minds of those who retained it.’

John MacAulay as a fifteen-year-old boy forty-five years ago, spending a season ‘at the fishing’ on the Monachs, to the west of Uist, heard stories from fishermen who had been out in the Sound of Shiant. On a wild day, they had hauled something or other very strange from the sea. They had no idea what it was. Other creatures of the same sort seemed to be visible in the surf around them and they didn’t like it. Nothing is easier than being spooked at sea in a small boat, and the Sound of Shiant seemed to be turning into that horrible continuity of white and broken water. All sense of one’s own fragility; the thumping of the hull against each new wave, the distance from shore, one’s own pitiable progress to windward, the sheer size of the cold, hateful sea, the knowledge of all the others that have been drowned here before you: your throat constricts, you feel it in your chest and the stories start to turn real.

The fishermen, rather than carry their mysterious catch back home in triumph or as a curiosity, threw it back into the thrashing water among its companions, and it was lost to sight. Surely not a Blue-Green Man? John MacAulay guesses that it might have been a walrus, of which one or two occasionally wander south from their Arctic breeding grounds, appearing here as enormous mustachioed aliens to Hebridean eyes. Donald MacSween is scepticism itself: ‘How have you got on with your investigations into the mermaids?’ he asks from time to time.

I wasn’t interested now. I was straining for the sight either of a Galta, a blessed gable-end, or of Damhag in front of me. Some of the swells were just breaking under their own weight. Behind me, the little grinning teeth of the breaking seas were scattered across the whole visible width of the Minch. Downwind I couldn’t see them. If I looked ahead of me, it was like a crowd from behind, a sea of wind-coiffed heads. The slick black-grey backs of the waves moved on in front of me. Scarcely any whiteness was apparent. It was like two different seas.