Полная версия

Stumbling on Happiness

That is, surprised. See?

Now, consider the meaning of that brief moment of surprise. Surprise is an emotion we feel when we encounter the unexpected–for example, thirty-four acquaintances in paper hats standing in our living room yelling ‘Happy birthday!’ as we walk through the front door with a bag of groceries and a full bladder–and thus the occurrence of surprise reveals the nature of our expectations. The surprise you felt at the end of the last paragraph reveals that as you were reading the phrase it is only when your brain predicts badly that you suddenly feel…, your brain was simultaneously making a reasonable prediction about what would happen next. It predicted that sometime in the next few milliseconds your eyes would come across a set of black squiggles that encoded an English word that described a feeling, such as sad or nauseous or even surprised. Instead, it encountered a fruit, which woke you from your dogmatic slumbers and revealed the nature of your expectations to anyone who was watching. Surprise tells us that we were expecting something other than what we got, even when we didn’t know we were expecting anything at all.

Because feelings of surprise are generally accompanied by reactions that can be observed and measured–such as eyebrow arching, eye widening, jaw dropping, and noises followed by a series of exclamation marks–psychologists can use surprise to tell them when a brain is nexting. For example, when monkeys see a researcher drop a ball down one of several chutes, they quickly look to the bottom of that chute and wait for the ball to reemerge. When some experimental trickery causes the ball to emerge from a different chute than the one in which it was deposited, the monkeys display surprise, presumably because their brains were nexting.[6] Human babies have similar responses to weird physics. For example, when babies are shown a video of a big red block smashing into a little yellow block, they react with indifference when the little yellow block instantly goes careening off the screen. But when the little yellow block hesitates for just a moment or two before careening away, babies stare like bystanders at a train wreck–as though the delayed careening had violated some prediction made by their nexting brains.[7] Studies such as these tell us that monkey brains ‘know’ about gravity (objects fall down, not sideways) and that baby human brains ‘know’ about kinetics (moving objects transfer energy to stationary objects at precisely the moment they contact them and not a few seconds later). But more important, they tell us that monkey brains and baby human brains add what they already know (the past) to what they currently see (the present) to predict what will happen next (the future). When the actual next thing is different from the predicted next thing, monkeys and babies experience surprise.

Our brains were made for nexting, and that’s just what they’ll do. When we take a stroll on the beach, our brains predict how stable the sand will be when our foot hits it, and then adjust the tension in our knee accordingly. When we leap to catch a Frisbee, our brains predict where the disc will be when we cross its flight path, and then bring our hands to precisely that point. When we see a sand crab scurry behind a bit of driftwood on its way to the water, our brains predict when and where the critter will reappear, and then direct our eyes to the precise point of its reemergence. These predictions are remarkable in both the speed and accuracy with which they are made, and it is difficult to imagine what our lives would be like if our brains quit making them, leaving us completely ‘in the moment’ and unable to take our next step. But while these automatic, continuous, nonconscious predictions of the immediate, local, personal future are both amazing and ubiquitous, they are not the sorts of predictions that got our species out of the trees and into dress slacks. In fact, these are the kinds of predictions that frogs make without ever leaving their lily pads, and hence not the sort that The Sentence was meant to describe. No, the variety of future that we human beings manufacture–and that only we manufacture–is of another sort entirely.

The Ape That Looked Forward

Adults love to ask children idiotic questions so that we can chuckle when they give us idiotic answers. One particularly idiotic question we like to ask children is this: ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ Small children look appropriately puzzled, worried perhaps that our question implies they are at some risk of growing down. If they answer at all, they generally come up with things like ‘the candy guy’ or ‘a tree climber’. We chuckle because the odds that the child will ever become the candy guy or a tree climber are vanishingly small, and they are vanishingly small because these are not the sorts of things that most children will want to be once they are old enough to ask idiotic questions themselves. But notice that while these are the wrong answers to our question, they are the right answers to another question, namely, ‘What do you want to be now?’ Small children cannot say what they want to be later because they don’t really understand what later means.[8] So, like shrewd politicians, they ignore the question they are asked and answer the question they can. Adults do much better, of course. When a thirtyish Manhattanite is asked where she thinks she might retire, she mentions Miami, Phoenix or some other hotbed of social rest. She may love her gritty urban existence right now, but she can imagine that in a few decades she will value bingo and prompt medical attention more than art museums and squeegee men. Unlike the child who can only think about how things are, the adult is able to think about how things will be. At some point between our high chairs and our rocking chairs, we learn about later.[9]

Later! What an astonishing idea. What a powerful concept. What a fabulous discovery. How did human beings ever learn to preview in their imaginations chains of events that had not yet come to pass? What prehistoric genius first realized that he could escape today by closing his eyes and silently transporting himself into tomorrow? Unfortunately, even big ideas leave no fossils for carbon dating, and thus the natural history of later is lost to us forever. But paleontologists and neuroanatomists assure us that this pivotal moment in the drama of human evolution happened sometime within the last 3 million years, and that it happened quite suddenly. The first brains appeared on earth about 500 million years ago, spent a leisurely 430 million years or so evolving into the brains of the earliest primates, and another 70 million years or so evolving into the brains of the first protohumans. Then something happened–no one knows quite what, but speculation runs from the weather turning chilly to the invention of cooking–and the soon-to-be-human brain experienced an unprecedented growth spurt that more than doubled its mass in a little over two million years, transforming it from the one-and-a-quarter-pound brain of Homo habilis to the nearly three-pound brain of Homo sapiens.[10]

Now, if you were put on a hot-fudge diet and managed to double your mass in a very short time, we would not expect all of your various body parts to share equally in the gain. Your belly and buttocks would probably be the major recipients of newly acquired flab, while your tongue and toes would remain relatively svelte and unaffected. Similarly, the dramatic increase in the size of the human brain did not democratically double the mass of every part so that modern people ended up with new brains that were structurally identical to the old ones, only bigger. Rather, a disproportionate share of the growth centred on a particular part of the brain known as the frontal lobe, which, as its name implies, sits at the front of the head, squarely above the eyes (see figure 2). The low, sloping brows of our earliest ancestors were pushed forward to become the sharp, vertical brows that keep our hats on, and the change in the structure of our heads occurred primarily to accommodate this sudden change in the size of our brains. What did this new bit of cerebral apparatus do to justify an architectural overhaul of the human skull? What is it about this particular part that made nature so anxious for each of us to have a big one? Just what good is a frontal lobe?

Fig. 2. The frontal lobe is the recent addition to the human brain that allows us to imagine the future.

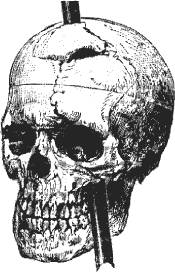

Until fairly recently, scientists thought it was not much good at all, because people whose frontal lobes were damaged seemed to do pretty well without them. Phineas Gage was a foreman for the Rutland Railroad who, on a lovely autumn day in 1848, ignited a small explosion in the vicinity of his feet, launching a three-and-a-half-foot-long iron rod into the air, which Phineas cleverly caught with his face. The rod entered just beneath his left cheek and exited through the top of his skull, boring a tunnel through his cranium and taking a good chunk of frontal lobe with it (see figure 3). Phineas was knocked to the ground, where he lay for a few minutes. Then, to everyone’s astonishment, he stood up and asked if a coworker might escort him to the doctor, insisting all the while that he didn’t need a ride and could walk by himself, thank you. The doctor cleaned some dirt from his wound, a coworker cleaned some brain from the rod, and in a relatively short while, Phineas and his rod were back about their business.[11] His personality took a decided turn for the worse–and that fact is the source of his fame to this day–but the more striking thing about Phineas was just how normal he otherwise was. Had the rod made hamburger of another brain part–the visual cortex, Brace’s area, the brain stem–then Phineas might have died, gone blind, lost the ability to speak or spent the rest of his life doing a convincing impression of a cabbage. Instead, for the next twelve years, he lived, saw, spoke, worked and travelled so uncabbagely that neurologists could only conclude that the frontal lobe did little for a fellow that he couldn’t get along nicely without.[12] As one neurologist wrote in 1884, ‘Ever since the occurrence of the famous American crowbar case it has been known that destruction of these lobes does not necessarily give rise to any symptoms.’[13]

Fig. 3. An early medical sketch showing where the tamping iron entered and exited Phineas Gage’s skull.

But the neurologist was wrong. In the nineteenth century, knowledge of brain function was based largely on the observation of people who, like Phineas Gage, were the unfortunate subjects of one of nature’s occasional and inexact neurological experiments. In the twentieth century, surgeons picked up where nature left off and began to do more precise experiments whose results painted a very different picture of frontal lobe function. In the 1930s, a Portuguese physician named Antonio Egas Moniz was looking for a way to quiet his highly agitated psychotic patients when he heard about a new surgical procedure called frontal lobotomy, which involved the chemical or mechanical destruction of parts of the frontal lobe. This procedure had been performed on monkeys, who were normally quite angry when their food was withheld, but who reacted to such indignities with unruffled patience after experiencing the operation. Egas Moniz tried the procedure on his human patients and found that it had a similar calming effect. (It also had the calming effect of winning Egas Moniz the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1949.) Over the next few decades, surgical techniques were improved (the procedure could be performed under local anesthesia with an ice pick) and unwanted side effects (such as lowered intelligence and bed-wetting) were diminished. The destruction of some part of the frontal lobe became a standard treatment for cases of anxiety and depression that resisted other forms of therapy.[14] Contrary to the conventional medical wisdom of the previous century, the frontal lobe did make a difference. The difference was that some people seemed better off without it.

But while some surgeons were touting the benefits of frontal lobe damage, others were noticing the costs. Although patients with frontal lobe damage often performed well on standard intelligence tests, memory tests and the like, they showed severe impairments on any test–even the very simplest test–that involved planning. For instance, when given a maze or a puzzle whose solution required that they consider an entire series of moves before making their first move, these otherwise intelligent people were stumped.[15] Their planning deficits were not limited to the laboratory. These patients might function reasonably well in ordinary situations, drinking tea without spilling and making small talk about the curtains, but they found it practically impossible to say what they would do later that afternoon. In summarizing scientific knowledge on this topic, a prominent scientist concluded: ‘No prefrontal symptom has been reported more consistently than the inability to plan…. The symptom appears unique to dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex…[and] is not associated with clinical damage to any other neural structure.’[16]

Now, this pair of observations–that damage to certain parts of the frontal lobe can make people feel calm but that it can also leave them unable to plan–seem to converge on a single conclusion. What is the conceptual tie that binds anxiety and planning? Both, of course, are intimately connected to thinking about the future. We feel anxiety when we anticipate that something bad will happen, and we plan by imagining how our actions will unfold over time. Planning requires that we peer into our futures, and anxiety is one of the reactions we may have when we do.[17] The fact that damage to the frontal lobe impairs planning and anxiety so uniquely and precisely suggests that the frontal lobe is the critical piece of cerebral machinery that allows normal, modern human adults to project themselves into the future. Without it we are trapped in the moment, unable to imagine tomorrow and hence unworried about what it may bring. As scientists now recognize, the frontal lobe ‘empowers healthy human adults with the capacity to consider the self’s extended existence throughout time’.[18]? As such, people whose frontal lobe is damaged are described by those who study them as being ‘bound to present stimuli’,[19] or ‘locked into immediate space and time’,[20] or as displaying a ‘tendency toward temporal concreteness’.[21] In other words, like candy guys and tree climbers, they live in a world without later.

The sad case of the patient known as N.N. provides a window into this world. N.N. suffered a closed head injury in an automobile accident in 1981, when he was thirty years old. Tests revealed that he had sustained extensive damage to his frontal lobe. A psychologist interviewed N.N. a few years after the accident and recorded this conversation:

PSYCHOLOGIST: What will you be doing tomorrow?

N.N.: I don’t know.

PSYCHOLOGIST: DO you remember the question?

N.N.: About what I’ll be doing tomorrow?

PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes, would you describe your state of mind when you try to think about it?

N.N.: Blank, I guess…It’s like being asleep…like being in a room with nothing there and having a guy tell you to go find a chair, and there’s nothing there…like swimming in the middle of a lake. There’s nothing to hold you up or do anything with.[22]

N.N.’s inability to think about his own future is characteristic of patients with frontal lobe damage. For N.N., tomorrow will always be an empty room, and when he attempts to envision later, he will always feel as the rest of us do when we try to imagine nonexistence or infinity. Yet, if you struck up a conversation with N.N. on the subway, or chatted with him while standing in a queue at the post office, you might not know that he was missing something so fundamentally human. After all, he understands time and the future as abstractions. He knows what hours and minutes are, how many of the latter there are in the former, and what before and after mean. As the psychologist who interviewed N.N. reported: “He knows many things about the world, he is aware of this knowledge, and he can express it flexibly. In this sense he is not greatly different from a normal adult. But he seems to have no capacity of experiencing extended subjective time…. He seems to be living in a ‘permanent present…’”[23]

A permanent present–what a haunting phrase. How bizarre and surreal it must be to serve a life sentence in the prison of the moment, trapped forever in the perpetual now, a world without end, a time without later. Such an existence is so difficult for most of us to imagine, so alien to our normal experience, that we are tempted to dismiss it as a fluke–an unfortunate, rare and freakish aberration brought on by traumatic head injury. But in fact, this strange existence is the rule and we are the exception. For the first few hundred million years after their initial appearance on our planet, all brains were stuck in the permanent present, and most brains still are today. But not yours and not mine, because two or three million years ago our ancestors began a great escape from the here and now, and their getaway vehicle was a highly specialized mass of grey tissue, fragile, wrinkled and appended. This frontal lobe–the last part of the human brain to evolve, the slowest to mature and the first to deteriorate in old age–is a time machine that allows each of us to vacate the present and experience the future before it happens. No other animal has a frontal lobe quite like ours, which is why we are the only animal that thinks about the future as we do. But if the story of the frontal lobe tells us bow people conjure their imaginary tomorrows, it doesn’t tell us why.

Twisting Fate

In the late 1960s, a Harvard psychology professor took LSD, resigned his appointment (with some encouragement from the administration), went to India, met a guru and returned to write a popular book called Be Here Now, whose central message was succinctly captured by the injunction of its title.[24] The key to happiness, fulfilment and enlightenment, the ex-professor argued, was to stop thinking so much about the future.

Now, why would anyone go all the way to India and spend his time, money and brain cells just to learn how not to think about the future? Because, as anyone who has ever tried to learn meditation knows, not thinking about the future is much more challenging than being a psychology professor. Not to think about the future requires that we convince our frontal lobe not to do what it was designed to do, and like a heart that is told not to beat, it naturally resists this suggestion. Unlike N.N., most of us do not struggle to think about the future because mental simulations of the future arrive in our consciousness regularly and unbidden, occupying every corner of our mental lives. When people are asked to report how much they think about the past, present and future, they claim to think about the future the most.[25] When researchers actually count the items that float along in the average person’s stream of consciousness, they find that about 12 per cent of our daily thoughts are about the future.[26]? In other words, every eight hours of thinking includes an hour of thinking about things that have yet to happen. If you spent one out of every eight hours living in my state you would be required to pay taxes, which is to say that in some very real sense, each of us is a part-time resident of tomorrow.

Why can’t we just be here now? How come we can’t do something our goldfish find so simple? Why do our brains stubbornly insist on projecting us into the future when there is so much to think about right here today?

Prospection and Emotion

The most obvious answer to that question is that thinking about the future can be pleasurable. We daydream about hitting a home-run at the company picnic, posing with the lottery commissioner and the door-sized cheque, or making snappy patter with the attractive teller at the bank–not because we expect or even want these things to happen, but because merely imagining these possibilities is itself a source of joy. Studies confirm what you probably suspect: when people daydream about the future, they tend to imagine themselves achieving and succeeding rather than fumbling or failing.[27]

Indeed, thinking about the future can be so pleasurable that sometimes we’d rather think about it than get there. In one study, volunteers were told that they had won a free dinner at a fabulous French restaurant and were then asked when they would like to eat it. Now? Tonight? Tomorrow? Although the delights of the meal were obvious and tempting, most of the volunteers chose to put their restaurant visit off a bit, generally until the following week.[28]? Why the self-imposed delay? Because by waiting a week, these people not only got to spend several hours slurping oysters and sipping Chateau Cheval Blanc ’47, but they also got to look forward to all that slurping and sipping for a full seven days beforehand. Forestalling pleasure is an inventive technique for getting double the juice from half the fruit. Indeed, some events are more pleasurable to imagine than to experience (most of us can recall an instance in which we made love with a desirable partner or ate a wickedly rich dessert, only to find that the act was better contemplated than consummated), and in these cases people may decide to delay the event forever. For instance, volunteers in one study were asked to imagine themselves requesting a date with a person on whom they had a major crush, and those who had had the most elaborate and delicious fantasies about approaching their heartthrob were least likely to do so over the next few months.[29]

We like to frolic in the best of all imaginary tomorrows–and why shouldn’t we? After all, we fill our photo albums with pictures of birthday parties and tropical holidays rather than car wrecks and emergency-room visits because we want to be happy when we stroll down Memory Lane, so why shouldn’t we take the same attitude toward our strolls up Imagination Avenue? Although imagining happy futures may make us feel happy, it can also have some troubling consequences. Researchers have discovered that when people find it easy to imagine an event, they overestimate the likelihood that it will actually occur.[30] Because most of us get so much more practice imagining good than bad events, we tend to overestimate the likelihood that good events will actually happen to us, which leads us to be unrealistically optimistic about our futures.

For instance, American college students expect to live longer, stay married longer and travel to Europe more often than averages[31] They believe they are more likely to have a gifted child, to own their own home and to appear in the newspaper, and less likely to have a heart attack, venereal disease, a drinking problem, an auto accident, a broken bone or gum disease. Americans of all ages expect their futures to be an improvement on their presents[32] and although citizens of other nations are not quite as optimistic as Americans, they also tend to imagine that their futures will be brighter than those of their peers.[33] These overly optimistic expectations about our personal futures are not easily undone: experiencing an earthquake causes people to become temporarily realistic about their risk of dying in a future disaster, but within a couple of weeks even earthquake survivors return to their normal level of unfounded optimisms.[34] Indeed, events that challenge our optimistic beliefs can sometimes make us more rather than less optimistic. One study found that cancer patients were more optimistic about their futures than were their healthy counterparts.[35]

Of course, the futures that our brains insist on simulating are not all wine, kisses and tasty bivalves. They are often mundane, irksome, stupid, unpleasant or downright frightening, and people who seek treatment for their inability to stop thinking about the future are usually worrying about it rather than revelling in it. Just as a loose tooth seems to beg for wiggling, we all seem perversely compelled to imagine disasters and tragedies from time to time. On the way to the airport we imagine a future scenario in which the plane takes off without us and we miss the important meeting with the client. On the way to the dinner party we imagine a future scenario in which everyone hands the hostess a bottle of wine while we greet her empty-handed and embarrassed. On the way to the medical centre we imagine a future scenario in which our doctor inspects our chest X-ray, frowns and says something ominous such as ‘Let’s talk about your options.’ These dire images make us feel dreadful–quite literally–so why do we go to such great lengths to construct them?