Полная версия

Stumbling on Happiness

Daniel Gilbert

Stumbling on Happiness

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2007

First published in Great Britain by Harper Press in 2006

Copyright © Daniel Gilbert 2006

PS Section copyright © Clare Garner 2007, except ‘Confessions of a Spoondigger’ by Daniel Gilbert © Daniel Gilbert 2007

PSTM is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

Daniel Gilbert asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007183135

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2009 ISBN: 9780007330683

Version: 2017-03-28

Praise

From the reviews of Stumbling on Happiness:‘The joy of this book lies in the reading … there are dozens of books that contain the science, but this one pulls it all together in the neatest, wittiest way possible. If you didn’t laugh at the parade of human folly laid out in this book, you’d have to cry. In fact, if you are like this reviewer you will giggle, splutter, guffaw and then possibly fall off your chair making weird wheezing noises’

Daily Mail‘A witty, insightful and superbly entertaining trek through the foibles of human imagination’

New Scientist‘A delight to read. Gilbert is charming and funny and has a rare gift for making very complicated ideas come alive. He walks us through a series of fascinating – and in some ways troubling – facts about the way our minds work. This is a psychological detective story about one of the great mysteries of our lives. If you have even the slightest curiosity about the human condition, you ought to read it. Trust me’

MALCOLM GLADWELL, author of The Tipping Point‘A cerebral, intelligent and extremely entertaining account of our lifetime quest for deep satisfaction. He eloquently combines philosophy and science to unravel the deep mystery of our baseline emotional state … he does for psychology what Bill Bryson did for evolution’

Scotsman‘Stumbling on Happiness is an absolutely fantastic book that will shatter your most deeply held convictions about how your own mind works. Ceaselessly entertaining, Gilbert is the perfect guide to some of the most interesting psychological research ever performed. Think you know what makes you happy? You won’t know for sure until you have read this book’

STEVE LEVITT, author of Freakonomics‘In Stumbling on Happiness, Daniel Gilbert shares his brilliant insights into our quirks of mind, and steers us toward happiness in the most delightful, engaging ways. If you stumble on this book, you’re guaranteed many doses of joy’

DANIEL GOLEMAN, author of Emotional Intelligence‘This is a brilliant book, a useful book, and a book that could quite possibly change the way you look at just about everything. And as a bonus, Gilbert writes like a cross between Malcolm Gladwell and David Sedaris’

SETH GODIN, author of All Marketers Are Liars‘Everyone will enjoy reading this book, and some of us will wish we could have written it. You will rarely have a chance to learn so much about so important a topic while having so much fun’

PROFESSOR DANIEL KAHNEMAN, Princeton University, Winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics‘Gilbert is a lively and amusing stylist… beautifully written and thoroughly researched’

Sunday Telegraph‘Gilbert is the most entertaining happiness thinker. In Stumbling on Happiness, there is much to admire’

Financial Times‘Scientific erudition enlivened by acerbic wit’

The Times‘Gilbert is every bit as funny as Larry David… [He] translates and makes sense of a vast array of scientific literature on perception, memory and imagination. Among other things, Gilbert explains why we learn so little from our mistakes. Almost every page delivers enjoyable riffs’

Washington Post‘A fascinating new book that explores our sometimes misguided attempts to find happiness’

Time‘Gilbert’s elbow-in-the-ribs social-science humor is actually funny… But underneath the goofball brilliance, [he] has a serious argument to make about why human beings are forever wrongly predicting what will make them happy’

New York Times‘[Gilbert is] an engaging and amiable writer, with a penchant for comedy and cracking wise … but though the delivery may often be antic, the matter is serious…. Reading his engaging, accessible book made me happy. Even if it won’t last’

The Globe and MailDedication

For Oli, under the apple tree

One cannot divine nor forecast the conditions that will make happiness; one only stumbles upon them by chance, in a lucky hour, at the world’s end somewhere, and holds fast to the days, as to fortune or fame.

Willa Cather, ‘Le Lavandou’, 1902FOREWORD

How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is To have a thankless child.

Shakespeare, King LearWHAT WOULD YOU DO right now if you learned that you were going to die in ten minutes? Would you race upstairs and light that Marlboro you’ve been hiding in your sock drawer since the Ford administration? Would you waltz into your boss’s office and present him with a detailed description of his personal defects? Would you drive out to that steakhouse near the new mall and order a T-bone, medium rare, with an extra side of the really bad cholesterol? Hard to say, of course, but of all the things you might do in your final ten minutes, it’s a pretty safe bet that few of them are things you actually did today.

Now, some people will bemoan this fact, wag their fingers in your direction, and tell you sternly that you should live every minute of your life as though it were your last, which only goes to show that some people would spend their final ten minutes giving other people dumb advice. The things we do when we expect our lives to continue are naturally and properly different than the things we might do if we expected them to end abruptly. We go easy on the lard and tobacco, smile dutifully at yet another of our boss’s witless jokes, read books like this one when we could be wearing paper hats and eating pistachio macaroons in the bathtub, and we do each of these things in the charitable service of the people we will soon become. We treat our future selves as though they were our children, spending most of the hours of most of our days constructing tomorrows that we hope will make them happy. Rather than indulging in whatever strikes our momentary fancy, we take responsibility for the welfare of our future selves, squirrelling away portions of our paycheques each month so they can enjoy their retirements on a putting green, jogging and flossing with some regularity so they can avoid coronaries and gum grafts, enduring dirty nappies and mind-numbing repetitions of The Cat in the Hat so that someday they will have fat-cheeked grandchildren to bounce on their laps. Even plunking down a dollar at the convenience store is an act of charity intended to ensure that the person we are about to become will enjoy the cupcake we are paying for now. In fact, just about any time we want something–a promotion, a marriage, an automobile, a cheeseburger–we are expecting that if we get it, then the person who has our fingerprints a second, minute, day or decade from now will enjoy the world they inherit from us, honoring our sacrifices as they reap the harvest of our shrewd investment decisions and dietary forbearance.

Yeah, yeah. Don’t hold your breath. Like the fruits of our loins, our temporal progeny are often thankless. We toil and sweat to give them just what we think they will like, and they quit their jobs, grow their hair, move to or from San Francisco and wonder how we could ever have been stupid enough to think they’d like that. We fail to achieve the accolades and rewards that we consider crucial to their well-being, and they end up thanking God that things didn’t work out according to our shortsighted, misguided plan. Even that person who takes a bite of the cupcake we purchased a few minutes earlier may make a sour face and accuse us of having bought the wrong snack. No one likes to be criticized, of course, but if the things we successfully strive for do not make our future selves happy, or if the things we unsuccessfully avoid do, then it seems reasonable (if somewhat ungracious) for them to cast a disparaging glance backward and wonder what the hell we were thinking. They may recognize our good intentions and begrudgingly acknowledge that we did the best we could, but they will inevitably whine to their therapists about how our best just wasn’t good enough for them.

How can this happen? Shouldn’t we know the tastes, preferences, needs and desires of the people we will be next year–or at least later this afternoon? Shouldn’t we understand our future selves well enough to shape their lives–to find careers and lovers whom they will cherish, to buy slipcovers for the sofa that they will treasure for years to come? So why do they end up with attics and lives that are full of stuff that we considered indispensable and that they consider painful, embarrassing or useless? Why do they criticize our choice of romantic partners, second-guess our strategies for professional advancement and pay good money to remove the tattoos that we paid good money to get? Why do they experience regret and relief when they think about us, rather than pride and appreciation? We might understand all this if we had neglected them, ignored them, mistreated them in some fundamental way–but damn it, we gave them the best years of our lives! How can they be disappointed when we accomplish our coveted goals, and why are they so damned giddy when they end up in precisely the spot that we worked so hard to steer them clear of? Is there something wrong with them?

Or is there something wrong with us?

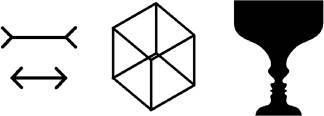

WHEN I WAS TEN YEARS OLD, the most magical object in my house was a book on optical illusions. Its pages introduced me to the Müller-Lyer lines whose arrow-tipped ends made them appear as though they were different lengths even though a ruler showed them to be identical, the Necker cube that appeared to have an open side one moment and then an open top the next, the drawing of a chalice that suddenly became a pair of silhouetted faces before flickering back into a chalice again (see figure 1). I would sit on the floor in my father’s study and stare at that book for hours, mesmerized by the fact that these simple drawings could force my brain to believe things that it knew with utter certainty to be wrong. This is when I learned that mistakes are interesting and began planning a life that contained several of them. But an optical illusion is not interesting simply because it causes everyone to make a mistake; rather, it is interesting because it causes everyone to make the same mistake. If I saw a chalice, you saw Elvis and a friend of ours saw a paper carton of moo goo gai pan, then the object we were looking at would be a very fine inkblot but a lousy optical illusion. What is so compelling about optical illusions is that everyone sees the chalice first, the faces next, and then–flicker flicker–there’s that chalice again. The errors that optical illusions induce in our perceptions are lawful, regular and systematic. They are not dumb mistakes but smart mistakes–mistakes that allow those who understand them to glimpse the elegant design and inner workings of the visual system.

Fig. 1.

The mistakes we make when we try to imagine our personal futures are also lawful, regular and systematic. They too have a pattern that tells us about the powers and limits of foresight in much the same way that optical illusions tell us about the powers and limits of eyesight. That’s what this book is all about. Despite the third word of the title, this is not an instruction manual that will tell you anything useful about how to be happy. Those books are located in the self-help section two aisles over, and once you’ve bought one, done everything it says to do and found yourself miserable anyway, you can always come back here to understand why. Instead, this is a book that describes what science has to tell us about how and how well the human brain can imagine its own future, and about how and how well it can predict which of those futures it will most enjoy. This book is about a puzzle that many thinkers have pondered over the last two millennia, and it uses their ideas (and a few of my own) to explain why we seem to know so little about the hearts and minds of the people we are about to become. The story is a bit like a river that crosses borders without benefit of passport because no single science has ever produced a compelling solution to the puzzle. Weaving together facts and theories from psychology, cognitive neuroscience, philosophy and behavioural economics, this book allows an account to emerge that I personally find convincing but whose merits you will have to judge for yourself.

Writing a book is its own reward, but reading a book is a commitment of time and money that ought to pay clear dividends. If you are not educated and entertained, you deserve to be returned to your original age and net worth. That won’t happen, of course, so I’ve written a book that I hope will interest and amuse you, provided you don’t take yourself too seriously and have at least ten minutes to live. No one can say how you will feel when you get to the end of this book, and that includes the you who is about to start it. But if your future self is not satisfied when it arrives at the last page, it will at least understand why you mistakenly thought it would be.[1]

PART I

Prospection

prospection (pro•spe•kshen)

The act of looking forward in time or considering the future.

CHAPTER I

Journey to Elsewhen

O, that a man might knowThe end of this day’s business ere it comes!Shakespeare, Julius CaesarPRIESTS VOW TO REMAIN CELIBATE, physicians vow to do no harm and letter carriers vow to swiftly complete their appointed rounds despite snow, sleet and split infinitives. Few people realize that psychologists also take a vow, promising that at some point in their professional lives they will publish a book, a chapter or at least an article that contains this sentence: ‘The human being is the only animal that…’ We are allowed to finish the sentence any way we like, but it has to start with those eight words. Most of us wait until relatively late in our careers to fulfil this solemn obligation because we know that successive generations of psychologists will ignore all the other words that we managed to pack into a lifetime of well-intentioned scholarship and remember us mainly for how we finished The Sentence. We also know that the worse we do, the better we will be remembered. For instance, those psychologists who finished The Sentence with ‘can use language’ were particularly well remembered when chimpanzees were taught to communicate with hand signs. And when researchers discovered that chimps in the wild use sticks to extract tasty termites from their mounds (and to bash one another over the head now and then), the world suddenly remembered the full name and mailing address of every psychologist who had ever finished The Sentence with ‘uses tools’. So it is for good reason that most psychologists put off completing The Sentence for as long as they can, hoping that if they wait long enough, they just might die in time to avoid being publicly humiliated by a monkey.

I have never before written The Sentence, but I’d like to do so now, with you as my witness. The human being is the only animal that thinks about the future. Now, let me say up front that I’ve had cats, I’ve had dogs, I’ve had gerbils, mice, goldfish and crabs (no, not that kind), and I do recognize that nonhuman animals often act as though they have the capacity to think about the future. But as bald men with cheap hairpieces always seem to forget, acting as though you have something and actually having it are not the same thing, and anyone who looks closely can tell the difference. For example, I live in an urban neighbourhood, and every autumn the squirrels in my yard (which is approximately the size of two squirrels) act as though they know that they will be unable to eat later unless they bury some food now. My city has a relatively well-educated citizenry, but as far as anyone can tell its squirrels are not particularly distinguished. Rather, they have regular squirrel brains that run food-burying programs when the amount of sunlight that enters their regular squirrel eyes decreases by a critical amount. Shortened days trigger burying behaviour with no intervening contemplation of tomorrow, and the squirrel that stashes a nut in my yard ‘knows’ about the future in approximately the same way that a falling rock ‘knows’ about the law of gravity–which is to say, not really. Until a chimp weeps at the thought of growing old alone, or smiles as it contemplates its summer holiday, or turns down a toffee apple because it already looks too fat in shorts, I will stand by my version of The Sentence. We think about the future in a way that no other animal can, does or ever has, and this simple, ubiquitous, ordinary act is a defining feature of our humanity.[2]

The Joy of Next

If you were asked to name the human brain’s greatest achievement, you might think first of the impressive artefacts it has produced–the Great Pyramid of Giza, the International Space Station or perhaps the Golden Gate Bridge. These are great achievements indeed, and our brains deserve their very own ticker-tape parade for producing them. But they are not the greatest. A sophisticated machine could design and build any one of these things because designing and building require knowledge, logic and patience, of which sophisticated machines have plenty. In fact, there’s really only one achievement so remarkable that even the most sophisticated machine cannot pretend to have accomplished it, and that achievement is conscious experience. Seeing the Great Pyramid or remembering the Golden Gate or imagining the Space Station are far more remarkable acts than is building any one of them. What’s more, one of these remarkable acts is even more remarkable than the others. To see is to experience the world as it is, to remember is to experience the world as it was, but to imagine–ah, to imagine is to experience the world as it isn’t and has never been, but as it might be. The greatest achievement of the human brain is its ability to imagine objects and episodes that do not exist in the realm of the real, and it is this ability that allows us to think about the future. As one philosopher noted, the human brain is an ‘anticipation machine’, and ‘making future’ is the most important thing it does.[3]

But what exactly does ‘making future’ mean? There are at least two ways in which brains might be said to make future, one of which we share with many other animals, the other of which we share with none. All brains–human brains, chimpanzee brains, even ordinary food-burying squirrel brains–make predictions about the immediate, local, personal future. They do this by using information about current events (‘I smell something’) and past events (‘Last time I smelled this smell, a big thing tried to eat me’) to anticipate the event that is most likely to happen to them next (‘A big thing is about to–’).[4] But notice two features of this so-called prediction. First, despite the comic quips inside the parentheses, predictions such as these do not require the brain making them to have anything even remotely resembling a conscious thought. Just as an abacus can put two and two together to produce four without having thoughts about arithmetic, so brains can add past to present to make future without ever thinking about any of them. In fact, it doesn’t even require a brain to make predictions such as these. With just a little bit of training, the giant sea slug known as Aplysia parvula can learn to predict and avoid an electric shock to its gill, and as anyone with a scalpel can easily demonstrate, sea slugs are inarguably brainless. Computers are also brainless, but they use precisely the same trick the sea slug does when they turn down your credit card because you were trying to buy dinner in Paris after buying lunch in LA. In short, machines and invertebrates prove that it doesn’t take a smart, self-aware, conscious brain to make simple predictions about the future.

The second thing to notice is that predictions such as these are not particularly far-reaching. They are not predictions in the same sense that we might predict the annual rate of inflation, the intellectual impact of postmodernism, the heat death of the universe, or Madonna’s next hair colour. Rather, these are predictions about what will happen in precisely this spot, precisely next, to precisely me, and we call them predictions only because there is no better word for them in the English language. But the use of that term—with its inescapable connotations of calculated, thoughtful reflection about events that may occur anywhere, to anyone, at any time–risks obscuring the fact that brains are continuously making predictions about the immediate, local, personal future of their owners without their owners’ awareness. Rather than saying that such brains are predicting let’s say that they are nexting.

Yours is nexting right now. For example, at this moment you may be consciously thinking about the sentence you just read, or about the key ring in your pocket that is jammed uncomfortably against your thigh, or about whether the War of 1812 really deserves its own overture. Whatever you are thinking, your thoughts are surely about something other than the word with which this sentence will end. But even as you hear these very words echoing in your very head, and think whatever thoughts they inspire, your brain is using the word it is reading right now and the words it read just before to make a reasonable guess about the identity of the word it will read next which is what allows you to read so fluently.[5] Any brain that has been raised on a steady diet of film noir and cheap detective novels fully expects the word night to follow the phrase It was a dark and stormy and thus when it does encounter the word night it is especially well prepared to digest it. As long as your brain’s guess about the next word turns out to be right, you cruise along happily, left to right, left to right, turning black squiggles into ideas, scenes, characters and concepts, blissfully unaware that your nexting brain is predicting the future of the sentence at a fantastic rate. It is only when your brain predicts badly that you suddenly feel avocado.