Полная версия

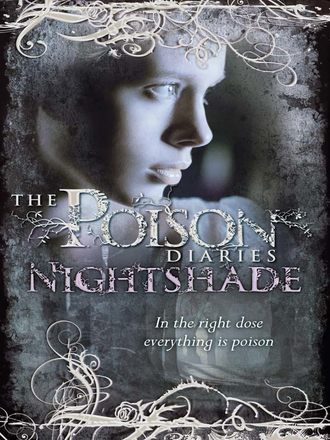

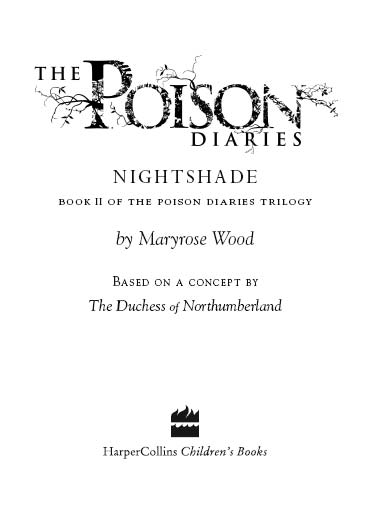

Poison Diaries: Nightshade

Dedication

For Ruta Rimas, with deepest thanks

Epigraph

“Weed… fills my head with tales from the ancient forests, tales so old that the trees themselves call them legends. It is as if a veil has been lifted from my eyes, and the world I have lived in all my sixteen years is revealed to be something else entirely, something so

marvellous I could never have imagined it…”

– JESSAMINE LUXTON, The Poison Diaries

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1

I WAKE, AS I usually do, to the sound of…

2

ALL DAY AND LATE into the evening, the fields ring…

3

A STAND OF HEMLOCK water dropwort grows in a sturdy…

4

IT IS LATE AFTERNOON when I return, though the sky…

5

DEEP IN THE FOREST is another world, yet three hours…

6

I AM ROWAN. I tell myself over and over, in…

7

THE JOURNEY SOUTH TAKES on a rhythm of its own.

8

THE NEXT MORNING I awaken early. I have only had…

9

THEY DRAG ME BACK to the King’s Head and sequester…

10

IT HAS TAKEN THE better part of this long sea…

11

THE COURTYARD OF SIGNORA Baglioni’s house is filled with weathered…

12

JESSAMINE LUXTON.

13

SIGNORA BAGLIONI BEGINS EVERY lesson the same way: “What does…

14

BE CHARMING, LOVELY. That was Oleander’s final instruction. These men…

15

THE TREE SIGNORA CALLS the Palm of St. Peter is the…

16

“BELLISSIMO,” SIGNORA BAGLIONI MURMURS, making the final adjustments to my…

17

I AM DYING, DROWNING at the bottom of the Tyne…

18

ARE YOU VERY WEARY, lovely? You must be. Even with…

19

THE PORTS OF PADUA and Venice were closed after word…

Other Books by Maryrose Wood

Copyright

About the Publisher

I WAKE, AS I usually do, to the sound of Weed’s voice. It rustles in my ear as I sleep. It skitters through my dreams like autumn leaves along the ground. My skin warms, my breath quickens. The memories come unbidden.

It is early spring, before I became ill. Weed and I are on one of our long rambles through the rolling green fields of Northumberland. He tells me strange fables, one after another, of a world where plants can speak, and all forms of life are of equal worth: humans, animals, and plants, too.

I laugh, because the tales are so marvellous. He turns to me, solemn-faced, and I explain my reaction.

“Marvellous? You may find them so. The trees are quite serious when they tell them.”

“But it is only a tale, a story – even to the trees, is it not? Look, here is a lovely place for our picnic. Shall we stop?”

How foolish I was then. How wrong I was, about so many things.

I thought love was a rare orchid that bloomed only once – but once it bloomed, it bloomed forever.

I thought that with the death of my mother, so many years ago, the worst of my life had already come and gone.

I thought my father would protect me from harm.

Was I wrong about Weed as well? Every time I draw breath I catch the earth scent of him. I lie motionless in my bed, alone in my tower bedchamber. A summer breeze floats through the open shutters, and I feel the tenderness of his kiss.

The last time I saw him I was dying. My mind flew with dark wings, and I looked down on my own pain-wracked body as if it belonged to another. I had nightmare visions of a strange prince who fed me poison, who wooed and tormented me, who showed me bloody scenes and unspeakable evils – evils wrought by my father.

My heart still pounds when I recall those hellish dreams. I thought I would not survive them. There were times I did not wish to.

More memories play on my half-closed eyelids as the morning sun tries to pry them open: Weed sitting at my bedside, spooning medicine to my lips. Wiping my brow. Gazing at me in love and grief, his moss-green eyes bright with tears.

Then he was gone. He lost hope and left. Too faithless to stay by my side until the end, he abandoned me at the worst point of my illness. That is what Father said, after my fever finally broke and I gasped and cried my way back to life, like a second birth.

“He is gone, and good riddance. He is a coward and a trickster. You are not the first maiden to be fooled by such a scoundrel. Bear your shame alone now; marry your work, and forget him, for you will not see him again.” Father said it coldly, and not without satisfaction.

Of course, what Father says cannot always be believed. But Weed is gone; that much is true. There has been no word, and now the summer draws to a close.

I stretch and turn beneath the cool linen sheet. I flex each limb and yawn, like a waking cat. Am I well? It is hard to say. In some ways I am stronger than I was. I am less trusting, less innocent. I have thoughts, sometimes, that I barely recognise as my own. I feel capable of things that I never would have dreamed of before.

I have even taken over my father’s healing practice. I had to; Father is too busy now, or too indifferent, to tend to people’s ills as he used to. With my knowledge of plants, it was not difficult to learn the basic cures, and they are most of what any healer needs. One fever, croup, or childbirth pang is much like another.

Once I walked through Northumberland hooded and silent, too shy to speak, too unimportant to approach. Now I am known and respected, and even a little bit feared. I do not mind that.

But there is an ache within, an empty place. My heart, once lush with joy, now lies fallow. Everything tastes like dust.

Weed, I have whispered a thousand times as I wandered alone through the meadows of Hulne Park. Where are you? Why did you leave? When will you come back to me? But the dull, ocean roar of the grass is the only answer I receive.

Tell him I love him still, I weep into the bark of an ancient pine. Tell him for me, please.

Still, I get no reply.

I long to drift back to sleep and bury myself in the bitter sweet dream of all that I have lost. But I must rise and dress. It is Sunday.

Yes, I go to church on Sundays, now. I go alone, for my father worships no god but knowledge. The tested, proven theories of long-dead men, as recorded in the musty books in the Duke’s library – those are his only sacred texts.

I myself have sometimes wondered what force could have put so many kinds of life on the earth, and made us need each other so, and hurt each other so, but I have not yet conceived of an answer. Still, to church I go, three miles on foot in the hot August haze. It is for my own protection. A woman who knows how to heal will always be suspected of witchcraft in these parts. The witch laws were struck down before I was born, but the people fear what they fear.

This is the north of England, after all; it is beautiful and raw here, and the land, the wind, and the sea have minds of their own. The people do, too. The north is not London, where the latest fashion is always best. In the north, the new is suspect, and the old ways die hard.

Like an apparition I glide silently into the chapel, so that everyone may see I am a virtuous and God-fearing young woman, and that my powers, such as they are, are drawn from nothing more sinister than a sprig of feverfew, a tisane of camomile, or a paste of crushed garlic and cloves.

“Good morning, Miss Luxton,” the people murmur as I pass. “Good day and good health to you.” When they ask about my father, and wonder why he no longer goes out, I say he is busy with his apothecary garden, or studying ancient cures at the Duke’s library at Alnwick Castle. The truth is that since my recovery, his frequent dark moods have knitted themselves into a ceaseless gloom. He works day and night, in his study or in the garden. At mealtimes he is silent; when we pass each other in the hall, he barely looks at me.

I thought I was alone before, before Weed came and I had only Father’s stern presence for company. Now Father is as lost to me as Weed is.

I sit stiff-backed in a pew, not far from the church doors. I stand when the preacher asks us to stand. I kneel when he tells us to kneel. When it is time to sing hymns, I raise my voice with the congregation, not so loudly that I draw attention to myself, but with enough force to be heard.

When the service is over I linger, my head bowed. Those who would beg my help approach me in turn: “Miss Luxton, the baby won’t stop coughing.” “Miss Luxton, a week’s come and gone and the wound won’t heal.” “Miss Luxton, it’s near my time, I need something to ease the birth pangs, will you come right away if I send my girl for you?”

One after another they tell me their aches, their pains, their worries. I nod in sympathy and promise to come when needed. Then I follow my fellow worshippers through the door, stepping from the cool, damp air of the church into the merciless noonday sun.

The preacher speaks to each one of us as we exit, gazing into our eyes, clasping our hands. He tells us to believe, so that we may be saved. “Hellfire is a thousand times hotter than this,” he warns, shaking a finger to the sky. “A thousand times a thousand! But you must believe!”

Outside the church the people gather in small, frightened groups and whisper, “The end of the world is nigh.”

They are righter than they know.

There – it has happened again. The words appear in my mind as if someone spoke them aloud. But there is no one here. It is as if my thoughts are not entirely my own.

And the voice – it chills my blood to admit it – but I have come realise that I know that voice. It is the voice from my nightmares. The voice of the evil prince.

He calls himself Oleander. The Prince of Poisons.

Shaken, I walk home from church, lay down my light summer shawl, eat a simple lunch of bread and cheese, alone. The cottage is quiet. Father must be out wandering the fields, or brooding behind the tall gate of his locked garden.

Once I thought of it as his apothecary garden, but now I know better. Those plants are poison, and the garden is something unnatural – a living weapon. Weed told me as much.

Your father has done me a great service, planting that garden. I hope he is not fool enough to think he is its master.

The words snake through my head, slow and inexorable, like oil spreading over water.

If so, he will pay the price someday, for that garden already has a master. One who will allow no pretenders to the throne.

There is a rap at the door.

I startle. Am I losing my mind? Is the dark prince of my nightmares standing outside my cottage this instant?

A charming thought, lovely. But I have no need of doors. All the locked gates in the world could not contain me. I enter when and where I wish. I hold the key to every poisoned heart.

The rap comes again, insistent. I remember the woman at church, the one who was heavy with child. Perhaps her pains have started. Trying to shake off this strange bout of madness, I grab my shawl and my medical bag and hurry to the door.

“I am ready,” I begin to say, but two men stand before me. Local men, both farmers. I have seen them before, at market day. Their awkward bulk fills the doorframe and blocks the slanted afternoon light.

“Miss Luxton?”

“Yes.”

The taller man glances at the bag in my hands. “Might we come in for a moment and speak with you? It won’t take long.”

I bid them enter and show them to the parlour, but I remain standing. “I would ask you to sit, but as you see I was just on my way out,” I say, gesturing with my bag. “I trust you are not ill? That is the usual reason for strangers to appear at my door.”

The men shake their heads and glance uncomfortably around the room, with its vaulted ceiling and tall, arched windows. Long ago this cottage was a chapel. Now it is our home. Is that why I am being curse with this strange madness? I think. Can the echo of a thousand unanswered prayers ever truly fade? Can a chapel be haunted?

My uneasy visitors wring their hats in their hands. The tall man speaks. “Sorry to detain you, Miss Luxton. We’re from the Association for the Prosecution of Criminal Acts and Undesirables. Me and Horace, here, we’re making enquiries in the neighbourhood, regarding the matter of – well, a missing person, you might say.”

“Dead person, he means.” His companion scowls. “Don’t drag this out, Ned, I’ll be wanting supper soon, and it’s a long way home on foot.”

Missing person – dead person. Surely they cannot mean Weed? I bite my lip hard, and use the pain to steady myself.

The one called Ned swallows and nods. “Miss Luxton, there was a travelling preacher who came and went through these parts. ‘Repent, repent,’ you know the type – anyways, the man hasn’t been seen for some time. A week ago his Bible turns up near the crossroads, buried deep in a hedge of bramble. A farmer from Alnwick found it. One of his lambs got tangled up in the thorns, see, and he had to cut out the branches to free it. It was a bit worse for the rain and sun – the Bible, I mean – but you could still read the name on the flyleaf.”

Ned pauses and wipes his face with a simple cotton square he extracts from a pocket. “Forgive me, miss. There’s more, but it’s not an easy story to tell to a young lady like yourself. Not far from the Bible was… was…”

“A pile of bones,” Horace interrupts. “Human bones. Picked so clean you’d think they’d been boiled for soup.” He cleans his teeth with his own dirty fingernail, as if to demonstrate.

His words bore into me, releasing a gush of dread from some deep reservoir inside. “The ravens of Hulne Park do their work swiftly,” I say, masking my fear. “I hope you will follow their good example, gentlemen. Why are you here?”

“The truth is, miss, we don’t much care what happened to this fellow. Good riddance, one might say. Who wants to hear all that gloom and doom? But as it turns out, the preacher had a wife, and they both were members of our association. Dues paid in full.” Horace shakes his head in disappointment. “Which means that we two are stuck with the job of investigating.”

“Couldn’t happen at a worse time, either,” Ned adds. “Right in the middle of the harvest.”

“Was it murder?” I say the word as if it meant nothing horrible – murder, murder, murder – a word like any other.

Horace snorts, a contemptuous laugh. “A man’s bleached bones don’t just fall out of the sky, do they?”

“God alone knows what happened.” Ned rolls his eyes heavenward. “And God alone metes final justice. But that don’t mean we can shut our eyes to this business. The association must perform its duty, Miss Luxton. That’s why we’re here. Allow me to ask: Do you have any knowledge of this matter? Firsthand, secondhand, or otherwise?”

“I do not.”

“Duly noted. Like we said, we’ve been making enquiries. We were told there was a young man living here. May we speak to him?”

I hesitate. “Why?”

They glance at each other before Horace replies. “The widow’s paid her dues. That means we have to find someone to prosecute. Otherwise the case’ll drag on and on, and we’ll never have a moment’s peace. We could pay her to drop it, but that’d cost us a king’s ransom.”

The two men stand there, fingering their hats, waiting for my answer. Deliberately I remove my shawl and take a seat. I must, for my legs have begun to tremble.

“So you wish to find some poor fool to charge with a crime? Whether or not he is guilty of it?” My voice is cool, my anger palpable – how like my father I sound!

“Guilty, innocent – it don’t have to be so formal as all that!” Horace smiles. “No doubt it was an accident, whatever happened. Words get exchanged. Push comes to shove. The preacher ends up with a bloody nose in the dirt. Your friend goes on his merry way, as any of us would, and that’s the last he thinks of it. How was he to know the preacher could die of such a feeble blow?”

To demonstrate, Ned cuffs Horace on the head. For a moment I wonder if I am about to witness a murder myself, but Horace grits his teeth and continues.

“We take your friend to the magistrate, where he apologises most sincerely and pleads the benefit of clergy. Then he stands there like a good lad while he gets his pardon.”

“A pardon?” I interject. “But a man is dead. Surely his widow will want justice. I would, if I were her.”

“Every man worth his salt loses his temper now and again. That’s how the magistrate’ll see it, you can be sure. It gets the widow off our backs and puts the whole matter to bed. We’ll pay your friend a day’s wages for his trouble, too.”

Ned grins; his teeth are yellow as a mule’s. “But there won’t be no hanging, that we can promise you.”

“Lay off the talk of hanging, you dumb ox, you’re going to frighten the girl.” Horace turns back to me. “Now that we’ve laid your worries to rest – can we speak to the young fellow?”

I stand and move to the window. “The youth you refer to goes by the name of Weed. He stayed here with us for a short while. He was a great help to my father with the work in the gardens. But he no longer lives here, and I have no knowledge of his whereabouts.”

I let my eyes drift downward, shy and maidenly. “I would like to speak to him as well. He left soon after” – I allow my voice to catch with emotion; why not? – “soon after my father suggested that we become engaged.”

My visitors exchange a look. They too were young men, once. And now that they know how I have been shamed and abandoned, perhaps they will leave me be.

“I see.” Horace’s voice is gruff. “Perhaps it would be best if we spoke to your father, then.”

“My father is out.” I wave my hand, as if to indicate the whole north of England and Scotland, too. “If you can find him, by all means, speak to him. Feel free to go outside and look. I will make tea while you do.”

Before they can catch breath enough to answer, I excuse myself and leave. How convenient it is to be a woman, sometimes! One can always use the kitchen as an excuse to escape men’s tedious conversations, their scheming and planning. Father has his work to hide behind, I think, and I have my kettle.

As I light the fire my mind wanders down strange paths. Dread churns within me – dread that, somehow, this preacher’s death has something to do with Weed’s disappearance. But what?

I take my metal canister of tea off the shelf. It is my own mixture of dried lavender blossoms and lemon balm, harvested from my garden and hung in the storeroom to dry. Weed helped me hang these stalks, I think. His hands touched these tender leaves, just as they touched me…

I measure the tea, crumbling the dried leaves through my fingers to release the sweet fragrance. As I do, I think how easy it would be to add a bit of this and that to the kettle – just enough to sicken my guests later on, when they are safe at home in their beds, with only their wives nearby to hear their cries. Or enough to kill them, and silence their annoying questions forever.

I do nothing of the kind, of course. Even after all I have seen, all I have suffered, all I have lost, I still know the difference between right and wrong.

Do you really, lovely? I find the distinction rather blurry, myself.

I am a healer, I think, blocking out the voice of evil. I will not kill.

But it is oddly comforting to know that I can.

20th August

This morning I treated a bad case of sunburn, rheumy eyes, and a deep wound made by a rusted nail that a careless farmer stepped upon. The last was the most serious, but if the farmer soaks his foot in a strong brew of sage and yarrow as I instructed, it ought to heal quickly.

In the afternoon I tended my kitchen garden, which shows signs of fatigue from this relentless heat. As do I, it seems. I wait in dread for the voice of Oleander to return. So far it has not.

I hope I am not going mad.

ALL DAY AND LATE into the evening, the fields ring with the sound of reaping. The scythe swings, and like solders grievously overmatched in battle, the grass falls, row after slaughtered row.

I witnessed it myself this morning, as I walked from farm to farm, dispensing cures, advice, and comfort. Now, as I sit here sewing, I try to imagine what Weed might have heard, if he had walked beside me – the cries of protest, perhaps, as the scythe swings once more.

Does the wheat despise us? I find myself wondering. Does it wish we were the ones slain?

My thoughts are scattered by a sharp sound, the pop and hiss of wood catching fire in the parlour hearth. That log, too, was once the living limb of a tree – perhaps one of the ancient ones from the forest, with their noble, spreading branches and strange tales.

“A fire in summer,” I say without looking up from my sewing. “Surely that is a waste of wood.”

Father straightens from the hearth with a grunt. “There is a storm on the way. When the wind howls like this, warmth is required.” He takes his chair and gazes into the flames. “I am worried about your health, Jessamine. Until now I have said nothing, trusting that time would be the best remedy, but my concern bids me speak at last.”

“Speak, then.” Already I am on my guard.

“It has been some time since your illness passed. To outward appearances you seem recovered, and go about your work without complaint.” Thoughtful, he gazes into the fire. “But there are days you lie late in your bed, as if reluctant to wake. Your skin is pale, but now and then your cheeks flush red, perhaps recalling some secret shame. At times you stare blindly into the air, as if conversing with phantoms. The stain of tears is ever present on your face.”

“There is no need to worry.” Anger kindles within me, but I will be cautious: My father must have some reason of his own for speaking this way. “My body is perfectly well.”

“Your body is young and strong, and can survive much. But what of your heart, Jessamine?”

I put down my needle and thread. “My heart will heal when Weed comes back.”

“I think not. I think your heart will only begin to mend when you accept that Weed is gone.” Finally he looks up from the fire and faces me. “Gone, and never to return.”

“I don’t believe you.” If he wishes to provoke me, he is succeeding. “Time and again you have told me that Weed left me – heartlessly ran off as I lay dying. Before I did not have the strength to argue. Now I do.”

“Calm yourself –”

“Weed loves me. If he is keeping away from me, there must be a reason.”

“I have told you the reason. He is a common scoundrel, who despoiled and abandoned you in the most unforgivable manner –”

“You have told me lies. For I know Weed would be at my side even now, unless some force was preventing him.”

“You have not had any word from him at all, then?”

“No. I have not.”

Father looks at me, strangely satisfied, and I realise, This is what he wanted – to know if I have heard from Weed. Why would he wish to know that?

I feel exposed, and look away to hide the tears that spring to my eyes.

Such passion! Such grief! It is most enticing, my lovely. A pity you waste it on that ridiculous boy, that callow, unwanted Weed…