Полная версия

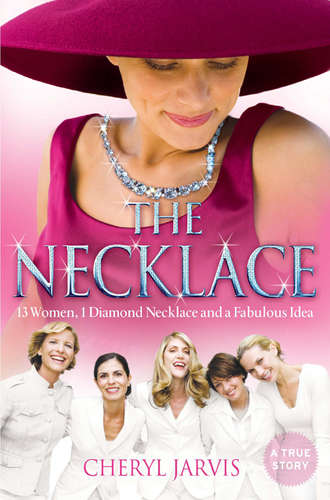

The Necklace: A true story of 13 women, 1 diamond necklace and a fabulous idea

JONELL SAILED OUT OF VAN GUNDY’S with the diamond necklace and a quick prayer that the other women would come through with their cheques. But she didn’t have time to worry about that now. She was throwing a party that evening and, being the last-minute hostess that she was, she still needed to clean the house and sweep the patio and pick up the food. But nothing could dull the excitement she felt at the thought of wearing the diamond necklace. At six o’clock, she slipped into her black yoga leggings and a silk zip-up top the colour of aubergines. Her philosophy of clothes was simple styles and the best of fabrics. She circled her neck with the diamonds and stared at them.

Looking in the mirror, she realised that the necklace was perfect for her. Her short blond hair, her frameless glasses, her minimalist make-up – the necklace looked good with all of it, including her one concession to glamour, her acrylic nails with their deep red varnish. She adjusted the arc of the diamonds to the scoop of her neckline.

No question, she thought, this necklace is amazing. I think I’ll keep it. The feeling of possessiveness vanished as quickly as it arose, but Jonell was astonished to discover that she had it at all.

The next week, Jonell composed her first e-mail to the women: ‘It’s about time we got this fabulous group together. Let’s meet Thursday, 11 November, at four p.m. Please come prepared to talk about the following: the necklace’s name, how to divide up the time, insurance, considerations (how we’ll refer to rules) and anything else that seems fun, relevant or not…You realise we have created the possibility of being in each other’s lives for the rest of the ride. I can’t wait to see what happens next.’

Priscilla Van Gundy read the e-mail. She’d forgotten all about the necklace and the deal her husband had negotiated; she’d probably repressed it since it was a financial loss for them. ‘Jeez,’ she thought, ‘Who’s got time for a meeting with a bunch of women?’ Her reply was terse: ‘I won’t be able to make it. I have to work.’

Seven kilometres away, Patti Channer read the same e-mail, relieved to see an agenda. Patti liked structure. She had agreed that the meeting could be held at her house, so she replied playfully to the e-mail: ‘I’ll be there.’

Well, she pulled it off, Patti thought to herself, remembering their conversation four weeks ago when Jonell had first approached her.

Patti had been driving around downtown Ventura, running errands and listening to a talk show on the radio when her mobile phone rang.

‘I want to run something by you,’ Jonell said in her typically excited way, talking faster than the rate of knots. Nothing unusual there. What Patti hadn’t heard before was Jonell speed-talking about – could it be jewellery? A diamond necklace? Patti pulled over to the kerb so she could focus.

‘If you and I could do this together and get ten others…’

The more Jonell talked, the more confused Patti became. How could Jonell want to spend money on something she’d always considered frivolous? Jonell hadn’t even bothered to replace some jewellery that had been stolen from her house. She’d met the loss with dismissal: ‘They were just things.’

When the two of them went shopping in Santa Monica last year, Patti bought an expensive shoulder bag of crochet-wrapped burgundy leather and Jonell was aghast. ‘How can you spend five hundred dollars on a handbag?’ she asked.

Patti defended the purchase as a piece of art. Jonell parried that with the fact that she could feed six people for a month with the money.

It was easy to understand how the two women had arrived at their different philosophies of spending. Jonell’s income from estate agency commission fluctuated, so she had to be careful to plan for the troughs with the money from the peaks. Patti’s income from managing her husband’s dental practice was steady. Jonell had two children she helped financially. Patti didn’t have children, so she didn’t have to deny herself. It’d been a running tension between them for the twenty-five years they’d been friends.

That shopping excursion had ended with division: Jonell disappeared into a bookshop while Patti dashed off to contemplate the purchase of a chiffon poncho that looked like a butterfly.

Patti’s thoughts were yanked back to the conversation by Jonell’s command: ‘You have to go and try it on.’

‘I don’t need to. I’m in.’

‘This could be a really great possibility.’

‘Fine, I’m in.’

‘You have to go and see it.’

‘Fine, fine, I’m in,’ she said for the third time.

Patti didn’t need convincing. The idea was so out of character for Jonell that Patti knew it’d be about something else and she knew it’d be interesting. Jonell was the only woman in Ventura who could have tempted her to say, ‘I’m in.’ She didn’t need to see it.

The next day, Patti stood in front of the window at Van Gundy’s. ‘Yes, it’s a gorgeous necklace; I’ll give Jonell that,’ she thought as she leaned into the display window. But it’s not something I’d buy for myself. At dinner that evening she talked to Gary about the necklace. Gary was the dashing dentist she’d been married to for thirty-five years. When he sauntered his six-foot-one-inch lanky self into his fortieth high school reunion, the women dubbed him both ‘best looking’ and ‘best preserved’. His brown hair didn’t have more than a few flecks of grey, and his curls were still thick.

After more than three decades together, she knew how Gary, a child of scarcity, would respond: ‘How much is it going to cost?’

‘A thousand dollars.’

‘You’re going to share it? That’s going to work?’

‘Of course it’s going to work. Women make things work.’

‘Well, maybe I’ll get the guys together and buy a Ferrari.’

‘You think that’s going to work?’

Gary laughed, and Patti volleyed with her deep raucous laugh.

Gary was sceptical that the ‘time-share’ would work and imagined some kind of bitchy Desperate Housewives scenario. But he’d found that married life went more smoothly if he didn’t interfere with Patti’s spending. She earned it, so she could do what she wanted with it. Gary chose to look on the bright side: at least now he’d never have to buy her a diamond necklace, thank god.

For the first gathering Patti readied her beach house, a cosy, earth-toned semidetached decorated with seascapes and shells, with a bedroom loft upstairs and a redwood sundeck outside. She set out cheeses – French Brie and Irish Dubliner – red and white wines and mineral water. She chilled a bottle of champagne in her silver wine bucket. She lit the gas fireplace, the white pillar candles on the mantelpiece, and the white votive candles on the coffee table. Patti had a flair for entertaining. This was a meeting, however, not a dinner party, so she’d decided on casual hospitality. She had no idea what was going to happen in her living room. She hoped it wouldn’t turn into a free-for-all.

At four o’clock, Jonell strode in carrying some soft drinks, and the others clinked in with bottles of wine and champagne. Soon the scene was like a replay of the one in Van Gundy’s – only with three times as many women, all talking at once. Each took a turn trying on the necklace in front of the mirror, immediately becoming the centre of attention as the others crowded around. Patti photographed each woman with her Sony Cyber-shot camera. Some patted the diamonds like society women in an Edith Wharton novel. Some effervesced like teenagers. Those who’d already tried it on in the shop tried it on again, but they did so hurriedly because that wasn’t what this meeting was about.

After the ceremonial Trying On of the Necklace, the women squeezed together on the taupe leather sofas and on ottomans and chairs scattered around the small living room. Jonell began the storytelling as if they were gathered around a fire at the beach. She talked about herself, her idea, her excitement, and this great group of women. After her narrative, she asked each woman to say something about herself. She couldn’t have known what the other women were thinking as they half-listened, half-analysed what they were doing in this living room, with these women and that necklace.

Eleven women – two couldn’t make it – all white. Eight blond, two brunette, one grey. Nine with wedding rings, one in heels.

Roz McGrath had been analysing the composition of the group as she looked around the room. ‘Where are the women of colour?’ she wondered. ‘Are there only two brunettes here?’ She was sceptical of blondes – in her experience she’d found most ‘blonde jokes’ too close to the truth. She didn’t know most of these women but she wanted them to know who she was. ‘I’m a feminist,’ were the first words out of her mouth.

Nancy Huff winced. ‘The seventies are over,’ she thought. ‘If this is going to turn into some consciousness-raising group I’m out of here.’ But she kept quiet.

When the last woman finished, Jonell started talking again: about her work, her husband, her kids, what this group was all about. She spoke so rapidly that some of the women had trouble keeping up with her. But her message was clear. ‘We are not what we wear or what we own,’ she said. In case they missed the point, Jonell took off her yellow cotton T-shirt, revealing a sheer camisole and an impish smile. Jonell’s old friends in the group, like Patti, had seen it all before. But what looked to them like an old hippie comfortable in her skin seemed different to the newer acquaintances. Some frankly noted Jonell’s great figure – lean stomach, firm arms, large breasts – but Roz McGrath was no longer the only one who wondered what she’d got herself into!

The next item on the agenda was to name the necklace. Jonell wanted to name it after Julia Child, the famous American cook and TV personality who’d died nearly three months earlier, on 13 August, 2004. The culinary idol had lived her later years in nearby Montecito, where Jonell’s husband had built the maple island in her kitchen. Naming the necklace for Child would be a fitting homage to this most admirable women. To Jonell, as well as to the women in the group who’d used her cookbooks and watched her TV show in the seventies, Julia Child introduced French cooking to Americans with an unpretentious style, an adventurous spirit and abundant humour. They appreciated that she hadn’t come into her own until she was in her fifties, but what they really applauded was her appetite for life. Several suggested spelling the name ‘Jewelia’.

Meanwhile, the rest remained quiet. They thought the idea of naming a necklace at all, let alone naming it for a cook, was absolutely ludicrous but no one said so.

Next on the agenda were the time-share arrangements. They agreed that each woman would have the necklace for twenty-eight days, during her birthday month. Only two women’s birthdates overlapped. Patti’s birthday was nine days away so, after they had discussed the rest of the business, she was first to take the necklace, and Jonell ended the meeting by ceremoniously clasping the diamonds around Patti’s neck.

‘Don’t lose it because it’s not insured yet,’ she said. ‘And have fun with it.’

Patti wore the fifteen-thousand-dollar necklace to bed that night but she didn’t sleep well. She woke up twice feeling panicky. Each time, she touched the necklace to make sure it still circled her neck, that it was in one piece and that nothing was broken. This was the first time since she was thirteen and had ‘borrowed’ her older sister’s gold charm bracelet that she’d worn something that didn’t belong just to her. The next morning she felt better, no longer afraid for the safety of the necklace. Still, she fretted over how to put into words what this experience was about. But even if she didn’t know exactly what to say, she decided she should look good saying it. She’d select her clothes carefully, choosing colours and styles that would complement the diamonds. That would be the easy part.

Patti Channer grew up the youngest of six children in Malverne, New York, a small dormitory community on Long Island. Her mother was a fashion aficionado who each season took her daughters on daylong shopping expeditions to the Garment District in Manhattan. First stop was either Saks or Bergdorf’s. At those upmarket department stores Patti’s mother studied the new designer styles. Then she’d take her daughters to Klein’s on Fourteenth Street, the best fashion discount outlet of that era. She knew just what to buy. She’d rummage through the piles of discounted designer garments and head back home with the right stuff. Whether by osmosis, training or something in her DNA, Patti developed a similar eye for fashion and an instinct for the deal.

According to all four daughters, their mother was a stunner, a stately woman who could wear designer clothes with style. She pulled her golden-red hair back in a French twist, kept her beautiful nails manicured, and always wore accessorised her outfits. She was known for her distinctive taste and for dressing her girls in style. She taught Patti and her sisters to take pride in their appearance, because she believed that clothes reveal personality. When Patti started dating boys, her mother instructed her: ‘Always look at a man’s shoes.’ When the family moved to the West Coast, Ventura was the thrift capital of Southern California and Patti’s mother was Queen of the Charity Shop. Patti never forgot finding a chandelier for four hundred dollars exactly like one her mother had bought for five dollars.

‘My love of shopping is genetic, and I consider myself a consummate shopper. I used to pride myself on being able to go into a shop and run my fingers over the fabrics and know which jacket was by one of the top designers. I was never wrong.’

It wasn’t surprising that Patti’s first job while in college was in retail. She worked for Abraham & Straus on Long Island, moving between different departments, and when she was assigned to the jewellery department she bought her first pair of good earrings. They were 14-carat-gold hoops, the size of a two-pence piece, the wires intricately bent into a serpentine design.

‘They were two hundred dollars – this was in 1970 – and I had to pay for them in instalments. I knew they were one of a kind. They made a statement. When I wore those earrings I felt special. Since that time, I’ve never gone out of the house without jewellery. Never.

‘Buying for many people is an aphrodisiac. If they’re sad, they go shopping, happy they go shopping, angry they go shopping. For me it’s the thrill of the hunt, finding the best quality at the best price. I rarely pay the full price. I found a beaded gauze top – a work of art – in a charity shop in Santa Barbara. I paid seventy-five dollars for it. Later when I pulled it out of the wardrobe to wear, I discovered the original price tag – thirteen hundred and fifty dollars. Another find! It felt orgasmic.’

Patti couldn’t feel the same ecstasy with regard to the group necklace – she hadn’t searched it out and struck the deal. But she knew from the start that this was something quite different than just another purchase.

‘Besides,’ she added, ‘I needed another necklace like I needed a hole in the head.’

The bedroom she shares with her husband is the perfect setting to discuss the necklace. In one corner, a bamboo hat rack is nearly invisible underneath handbags – quilted and jewelled and beaded bags, feather and leather, leopard and velvet bags, today’s and yesterday’s bags. And then there are the boas! Long ones, short ones, they come simple and sequinned, in red and chocolate and purple and pumpkin. In another corner, flowing over a wrought-iron quilt stand are wraps and more wraps – silk, woven, textured, fringed. A velvet wrap with mink pom-poms, a black suede wrap with cut-out fringe and a thick felt wrap with oversized pockets. On the bottom shelf of the stand a wicker basket cascades with scarves of cashmere and chenille, painted silks in olive and aubergine, a gold-and-black-sequinned scarf twists into a belt, then a headband, then a necklace.

No matter what Patti drapes around her lean body, she looks good in it. She has a compellingly photogenic face and at nearly five feet, seven inches, she has enviable blonde hair, thick and wavy, a healthy, outdoor glow, and long limbs seemingly always in motion. Her hazel eyes literally glisten when she smiles – and as Patti gives a tour of her bedroom, she smiles a lot.

More accessories fill the cherrywood dressing table: headbands and sunglasses and reading glasses, all jewelled and tortoiseshell and multicoloured and decorated for the holidays. In her walk-in wardrobe there are berets in every colour, dozens of belts and 150 pairs of shoes. ‘When I go to Las Vegas, I don’t gamble. I buy shoes,’ she says. ‘The boutiques at Caesars Palace have shoes you won’t find anywhere else in this country. I don’t buy the kind of things everyone else has. I don’t go to high-street chains unless I need socks. I like flea markets and charity shops.’

And then there’s the jewellery. On one wall, hanging from three etched glass hooks, dangle necklaces galore: chains and beads, rhinestones and pearls, chokers and pendants. In the dresser next to the hooks, she’s filled drawers with bracelets and bangles, plus jewellery inherited from her mother and jewellery for every holiday: brooches and earrings shaped like wreaths, pumpkins, shamrocks and flags.

In the wardrobe, there’s a fifty-four-pocket hanging jewellery holder with a pair of earrings in every section; and a thirty-pocket quilted case with jewellery in every section. More necklaces of multiple strands, multiple colours, necklaces made of pearls, gemstones, glass. ‘I have a mix of good and fake,’ she says. ‘If you have enough good, you can mix in the fake.’ Patti pulls out a necklace of burgundy silk cording with a tasselled ivory pendant hanging from a burgundy alligator spectacle case. She adjusts it around her neck, flips open the spectacle case, cocks her head to one side, then flashes a huge grin. ‘Would you look at this?’

There isn’t a drawer, a shelf, a stand or a chest without hidden stashes and caches of jewellery. The only place Patti doesn’t keep it is in a safe.

‘After we bought Jewelia a neighbour showed me her diamond necklace, which she keeps locked up. Other women I know make copies of their jewellery and wear the copies. If you’re going to do that, what’s the point of having it? That first month the necklace was mine to wear, I made the conscious decision that I’d wear it every day.’

During her first month with the necklace, Patti wore it to go body-boarding at a family wedding in Oahu, Hawaii; she wore it when she scored a very respectable 95 on eighteen holes of golf; and when helping to hose down a neighbourhood fire. She wore it to her husband’s paediatric dental practice, where she worked, and she wore it to the orthopaedic clinic when Gary underwent shoulder surgery. Then she donned the diamonds every evening while she worried about the aftermath of the operation. As she dragged on her cigarettes on the patio, she wondered if they would have to sell the practice? Would she be out of a job too, after twenty-nine years of running their office, managing the staff, coordinating the schedules and handling the books? For a while he’d been the only paediatric dentist in town, which meant seeing thirty to forty patients a day. That had been a lot of work, but gratifying too. She knew that her business sense had helped to make the practice successful. And Patti had met dozens of interesting women when they brought in their kids. In fact, that was the way she’d met Jonell.

What if they did have to sell up? For the first time in her life, this turn of events made Patti feel uncertain about the future. She was sick of people asking her if she was looking forward to retirement. No, she wasn’t looking forward to doing nothing. She was high-energy and always had been. She hated that word ‘retirement’ – really, she thought society should think of a new one. Gary was happy at the prospect, but Patti struggled with the unknown that lay ahead, grew restless just thinking about it. The necklace gave her something else to think about.

Everywhere she went – and Patti went everywhere – she talked about the necklace. Patti was a talker – not a rapid talker like Jonell, but a memorable talker. More than her one-of-a-kind accessories, what distinguished Patti was her Long Island accent. She left New York in 1975, but the accent didn’t leave her. Considering it another accessory, she kept it. When she talks, her hands move constantly, her fingers snapping to make a point, her beautiful, natural nails tap-tap-tapping on the table, the steering wheel, whatever surface is handy. When she walks, she recalls the dynamism of the streets of Manhattan, ever alert, moving quickly, with a stride befitting someone who completed the famous Waikiki Roughwater Swim over almost 4 kilometres of Pacific Ocean. On the streets downtown she talks to everyone – she knows everyone. She calls them ‘doll’, ‘babe’, ‘honey’, ‘lovey’, like a waitress in a lorry drivers’ café. She tells everyone she bumps into the story of the necklace.

People reacted to the necklace in varied ways. Some marvelled, some shrugged, some attacked. ‘What do you think you’re going to do with it?’

Patti didn’t have an answer for that one. That comment made her think: ‘What are we going to do with it?’ Scornful comments didn’t make her doubt what she’d done; they made her wonder if there was a better way to tell the story. So she changed a detail here, an anecdote there, and she kept talking.

‘It surprised me how much fun it was to talk about it. I liked the story of the deal – that is, getting the necklace for the price we did – but mostly I liked the story of the sharing. I liked that it was another conversation I could have with people. I had no idea where we were going with this, no idea where the necklace was going. Hell, I had no idea where I was going. But I was looking forward to finding out.’

Patti had just two more days left of her four weeks with the necklace when one of the other women – who? – asked to borrow it for a dinner dance. Patti said, ‘Sure.’ But when the necklace came back the next day Patti didn’t want it any more.

‘I’d enjoyed wearing it too much,’ she says. ‘I didn’t want to become reattached, then have to let it go a second time.’ It was time to pass it on.

Later, with the women, Patti talked about the possessiveness that surprised her and made her feel guilty and embarrassed. It reminded her of Gollum in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy – the character who became mentally tortured and physically wretched from his obsessive desire for the One Ring, ‘his precious’. Patti called the necklace ‘my pretty’ and her difficulty in letting it go ‘the Gollum effect’.

‘In talking about it,’ says Patti, ‘I realised that what made the necklace exciting to wear wasn’t the necklace itself. If I’d wanted a diamond necklace, I would have bought one a long time ago. What made it exciting was the story behind it. Getting to tell the story was what I’d become attached to.’

Before Patti’s turn with the necklace would come around again the following year, she and Gary would sell his dental practice and their lives would change in many ways. The group of women changed as well, with two members leaving, and a few tensions being aired and resolved.

During that first year Jonell, a voracious reader, gave the group a reading list and their first assignment: a book called Affluenza by three men no one had heard of. Jonell liked context. ‘If we’re going to talk about the necklace,’ she enthused, ‘this book will give us a frame of reference, make us more knowledgeable and effective.’

Mary O’Connor, one of the women in the group, was a former English teacher and an avid reader of literary fiction. She had no interest in self-help books. ‘If I’d wanted a reading group,’ she thought, ‘I would’ve joined one.’ But she kept quiet.

Nancy Huff was quiet, too, while thinking the same thing.

In fact, the group’s reaction to the reading assignment was less than enthusiastic, with almost half the group failing to read the book and the other half not even turning up to the meeting where it was to be discussed.