Полная версия

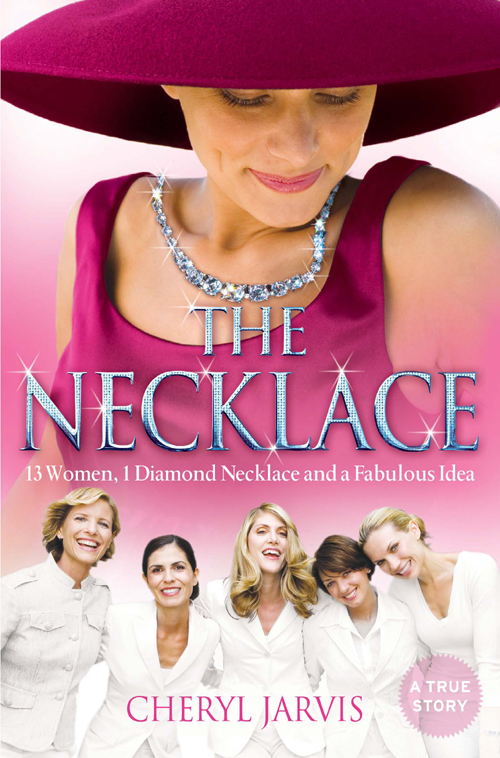

The Necklace: A true story of 13 women, 1 diamond necklace and a fabulous idea

The Necklace

A true story of 13 women, 1 diamond necklace and a fabulous idea

Cheryl Jarvis

For our families and friends and for women everywhere who imagine possibilities

Here we are, women who have been the beneficiaries of education, resources, reproductive choice, travel opportunities, the Internet and a longer life expectancy than women have ever had in history. What can and will we do?

– Jean Shinoda Bolen

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

PREFACE

CHAPTER ONE Jonell McLain, the dreamer

CHAPTER TWO Patti Channer, the shopping queen

CHAPTER THREE Priscilla Van Gundy, the loner

CHAPTER FOUR Dale Muegenburg, the stay-at-home wife

CHAPTER FIVE Maggie Hood, the adventurer

CHAPTER SIX Tina Osborne, the reluctant

CHAPTER SEVEN Mary Osborn, the competitor

CHAPTER EIGHT Mary Karrh, the practical one

CHAPTER NINE Nancy Huff, the extrovert

CHAPTER TEN Roz Warner, the leader

CHAPTER ELEVEN Jone Pence, the designer

CHAPTER TWELVE Mary O’Connor, the rock’n’roller

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Roz McGrath, the feminist

CHAPTER FOURTEEN The Experiment

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PREFACE

ON THE 18TH OF SEPTEMBER 2004, thirteen women in Ventura, California clubbed together to buy a diamond necklace. Within months the media had picked up their story. People magazine ran a feature. Katie Couric reported on the venture for the Today show. Other segments followed on magazine and news programmes in Los Angeles. Fox Searchlight Pictures bought the movie rights. Because the group was in its infancy, the flurry of news stories barely got beyond the purchase. No one knew then where the necklace would lead, least of all the thirteen women who’d bought it.

How would sharing a necklace work? Would there be catfights and chaos? Did they all want the same thing from the experiment? Would friendships fizzle and marriages falter? How would it affect them all?

Here’s the whole story, the real story, from the first sparkle.

CHAPTER ONE Jonell McLain, the dreamer

Making an idea happen

JONELL MCLAIN WAS SITTING LOOKING at the piles of paper that surrounded her, struggling not to feel overwhelmed. She wondered why she could never clear her desk, never cross off the forty-five tasks on her to-do list. Were there always forty-five things on that list? It certainly seemed that way. She felt like Sisyphus, the king in the Greek legend who was condemned to push the same rock up a mountain, over and over again. Some days she felt as though all she accomplished was moving piles from one corner of her desk to another. Some papers she could swear she moved a hundred times. Part of the problem was that she was full of ideas, so she was continually adding new projects to the list. Executing them – well, that was a skill she hadn’t yet totally mastered.

Today, the list didn’t make her feel as queasy as it often did. She’d just completed a deal on a house and was feeling the high that estate agents get when they finally receive their big commission cheques. This one represented three months of work and emotional exhaustion. People bought homes when they were undergoing major life changes, so naturally they were on edge, but the shock of prices on the West Coast made buyers moving to California especially anxious.

Because the work was so stressful, Jonell always rewarded herself after each deal was completed. She hadn’t decided what to buy herself this time but she headed to the shopping centre to buy her clients a luxurious box of chocolates, part of a gift basket she’d leave to welcome them to their new home.

The Pacific View Mall was the only shopping centre in Ventura, a California beach town 96 kilometres north of Los Angeles. Jonell walked quickly through the dusty-pink shopping enclave, slowing only to glance into the windows of Van Gundy & Sons, a decades-old, family-owned jewellery shop – the Tiffany’s of Ventura. And despite her errand, she came to a stop. She stared.

In the centre display case a diamond necklace glittered against black velvet. A few years earlier she’d searched unsuccessfully for a simple rhinestone necklace to wear to a formal event. Now here it was, the exact one she’d had in mind. The diamonds were strung in a single strand all the way to the clasp; the centre diamond was the largest and the two closest to the clasp the smallest. The gradations were minuscule, the effect breathtaking.

But this was Van Gundy’s. There was no way this necklace was made of rhinestones.

Jonell rarely wore good jewellery, though she owned a little of it – diamond wedding rings from two husbands, 14-carat-gold earrings, pricey watches. Luxury jewellery was something else. She wondered what a really expensive piece of jewellery looked like up close. What would it feel like to wear something so beautiful and extravagant?

On a whim she entered the shop. ‘Could I see the necklace in the window?’ she asked nonchalantly, as if she did this every day.

She reached up to touch the delicate gold chain she wore. Back in 1972 a boyfriend had given her this necklace, which had a peace symbol pendant, and in 2003, at the start of the war in Iraq, she’d put it on again. She placed the diamond stunner over her old gold charm. It was, she thought, simply exquisite – and exquisitely simple.

She took a breath, and as she breathed out, she asked the price.

‘Thirty-seven thousand dollars.’

Jonell couldn’t stop herself gasping. All she could think was: ‘Who buys a thirty-seven-thousand-dollar necklace?’

She looked in the mirror again. She thought back to the choices she’d made in her life, the ones that guaranteed she could never afford a necklace like this. She thought about how different her life might have been if she’d invested herself more in a career or married a wealthy man. If she’d worked harder, maybe she could have generated the kind of money that would enable her to indulge in this kind of luxury. In the end, none of this mattered, not really. In a world overflowing with need, the idea of owning a thirty-seven-thousand-dollar necklace was morally indefensible to Jonell, who’d acted as a mentor for disadvantaged kids for six years. Lost in these thoughts, she heard only snippets of the saleswoman’s description: ‘118 diamonds…brilliant-cut…mined from non-conflict areas…15.24 carats.’

Fifteen carats sounded ostentatious and Jonell didn’t like ostentation. She looked at it again. There was nothing ostentatious about this necklace. The diamonds were so small, just right for her five-foot-two-inch frame, yet circling clear around her neck they felt substantial. What was magnetic was their radiance. She’d never seen diamonds shimmer like these.

Jonell hesitated to take off the necklace. After admiring it for another minute, she laid it back on the counter and thanked the saleswoman for her time.

Over the next three weeks Jonell was surprised how often she thought about the diamond necklace. When she was next back at the shopping centre with her eighty-six-year-old mother, she noticed it was still in the window.

‘Mum, I want to show you something,’ she said, and led her mother into the shop as if she were seven and heading for her first Barbie doll. ‘Try it on.’

Her mother’s eyes widened as she clicked the clasp. ‘It’s beautiful,’ she whispered. Jonell’s mother knew quality, and her admiration confirmed for Jonell that the necklace was classic, timeless.

When Jonell peeled her eyes away from the diamonds brightening her mother’s neck, she glanced at the price tag: twenty-two thousand dollars. It had been reduced. And then, on the counter, she noticed an advert announced a sale in which the shop would take bids on any item of jewellery on display.

Jonell remembered being thirty and in need of a respite. Burned out from her job as a speech therapist in Santa Cruz and weary of her long-term boyfriend, she’d gone to New York City to live with her best friend from her final year at the University of Southern California. There, Jonell witnessed her room-mate washing her face with Perrier water. She saw her wrap herself in a full-length lynx coat. That’s when Jonell took stock of her own chances for such luxuries. They were slim to nil. That reality aroused not envy but curiosity: why was luxury accessible to so few? After six months, Jonell left New York to return to her native California, but the question had never left her. Now it loomed large again.

Why is it, she wondered, that we can stand shoulder to shoulder to enjoy sumptuous masterpieces in art museums? That whole crowds can admire magnificent landscapes together in national parks? Why can’t we share personal luxuries the same way?

And an idea was born: ‘I could wear a luxury item if I bought it together with some other women. No one woman needs to have a fifteen-carat diamond necklace all the time. But’ – and here she paused as the idea took shape – ‘wouldn’t it be delightful to have one every now and then?

‘I can’t spend twenty-two thousand dollars on myself, but I can spend one thousand…A thousand dollars would not be out of reach for many of my friends…If I could convince, say, at least another eleven women to come in with me, I could bid twelve thousand…It’s already come down by fifteen thousand dollars. Why not another ten?’

And so the idea was born. Jonell started phoning friends and colleagues immediately. She talked to the women in her walking group and investment club. Women she’d met at seminars, parties, charity events, tempting them with the idea of owning an amazing diamond necklace for one month each year. Most of the women she approached said no. No money. No time. No interest in diamonds. The responses fired off rapidly: ‘A formula for disaster. Everyone will fight over it.’ ‘What’s the point of buying diamonds?’ ‘I can get a better deal at the jewellery market.’ ‘You’ll never get twelve women to get along with each other.’ ‘If I’m going to spend a thousand dollars, I want something just for myself.’

Even her mother fired off a round: ‘You’ll lose friends over this.’

Some comments unsettled Jonell, filling her with self-doubt. Some spurred her to argue. Some she ignored. But she stayed fixed on her goal. She went back again to the women who’d said no. She asked new women. By two months later she had a group of seven. Close enough, she decided. She could put the balance on her Visa card and by the time the bill arrived, she’d have found the rest.

Three generations of Van Gundy men were in the shop on the Saturday of the sale: Kent Van Gundy, age eighty, who’d started the business in 1957 and was now retired; Tom Van Gundy, fifty-four, his son, who’d taken over the business; and Sean, twenty-nine, his grandson, who now managed the shop.

Tom says he’ll never forget that day. Sean won’t forget it either. These women were different from the ones the Van Gundys usually encountered. So many women who come into jewellery stores aren’t happy, says Sean. Their eyes are anxious, their faces tense. Some are in tears. They’re lonely and looking for someone to talk to. Something’s missing in their lives, and they’re trying to fill the empty space. These women rushed into the shop smiling, eager to be there shortly after the doors opened to beat any competing bidders. Jonell showed the necklace to the four who came with her: two who’d said yes to her proposition, two who’d said no but didn’t want to miss the fun. Mary Karrh, a head taller than Jonell, found herself so far removed from her daily life as an accountant that her expression was one of wonder. If she’d had any fears about what she’d committed her money to, they disappeared once she was face-to-face with the diamond necklace.

‘Wow, it looks like a million bucks,’ she said.

‘Try it on, Mary,’ Jonell urged.

The other women huddled around Mary, who found herself standing even taller. She sounded surprised as she said, ‘I can see myself wearing this.’

Maggie Hood represented the quintessential California girl with blonde hair and a firm body. She moved back and forth, one minute admiring the necklace, the next flirting with a good-looking salesman.

‘We need pictures!’ said Jonell. One of the women along for the camaraderie ran out into the shopping centre to buy a disposable camera.

Each woman – Jonell, Mary, Maggie, the two friends – posed for a photo with the diamonds. They vamped and giggled, amazed that three of them were even thinking of buying such a thing, even as a ‘time-share’. Obviously these giddy women didn’t buy diamonds every day. Throughout the posing, there was awe. ‘It’s so beautiful,’ they said. They said it over and over. They said it when they saw it on one another and when they looked at themselves in the mirror. They breathed it when Mary wore it with her sleeveless shirt and khaki shorts. They repeated it when Maggie tried it on with her vest top and jeans. And they sighed it as the diamonds lay against Jonell’s gold peace symbol charm. ‘This necklace is so beautiful!’ The women swept everyone up in their excitement as they grinned and gushed – and anticipated.

Then it was time for Jonell to hand Tom Van Gundy an envelope. In it was a sheet of paper with her handwritten bid and the names of twelve women, four of them followed by question marks. As she proffered her bid, she was confident and her grin playful but she was nervous. She was asking him to cut his price nearly in half. She was grateful for her estate agency experience in negotiating prices but she knew all too well that coming in with a low bid was a gamble.

The scene had caught all three Van Gundy men in its headlights. Nothing like this had ever happened in their shop. It wasn’t just the buzz in the place. In a quarter of a century of working in the business, Tom Van Gundy couldn’t recall seeing a single woman buy expensive jewellery for herself. Women fuelled the desire but they waited for the men in their lives to make the purchase.

Tom almost hated to take his eyes off these spirited women to look at their bid: twelve thousand dollars. He winced inwardly. Jewellery shops can have large mark-ups – that’s the reason why so many chain jewellery stores offer discounts of up to 70 per cent. Being in the jewellery business meant being a negotiator, and in this shop Tom usually handled negotiations himself. However, on high-priced items – and this was definitely a high-priced item – he needed clearance. This time it might be tough to get. Still, he managed to look and sound kind when he said to Jonell, ‘I need to have a look at the figures.’

He went to the back room. Priscilla Van Gundy, his wife and chief financial officer, was there, hunched over the books, hyper-focused, trying to tune out the noise. She usually worked in the administrative office across the street, but because of the sale she was squeezed in the store’s small stockroom between shelves of inventory and a desk that doubled as a kitchen table.

Priscilla had heard the commotion. She’d heard the salespeople talking about the group of women, but she hadn’t left her desk to go and have a look. She avoided looking at customers’ faces. She didn’t want negotiations to get personal.

‘There’s a group of women who want a special price on the diamond necklace,’ Tom said to the thick auburn hair hiding his wife’s face. ‘What can we sell it for?’

Priscilla tapped figures into the calculator: one for the actual cost of the necklace, another for the number of months it had been in the store, a third for what they needed to make a profit.

‘Eighteen thousand,’ she said.

Tom knew the number wasn’t going to be acceptable, but he was used to the to-and-fro of negotiations. He went back to the front of the shop to counter Jonell’s bid with Priscilla’s offer.

‘Not low enough,’ Jonell said. ‘We only want to spend a thousand per woman.’

Tom had anticipated the answer. He nodded his head and returned to the back room.

‘Can we go any lower?’ he asked Priscilla.

She felt his apprehension. After thirty-three years of marriage she could read his emotions like a spreadsheet. She turned to the calculator again, tapping in more numbers.

‘Seventeen thousand,’ she answered.

Tom scratched out the twelve-thousand-dollar figure on Jonell’s sheet of paper, scribbled fifteen thousand, and showed it to Priscilla.

‘Can we do this?’ he asked.

‘That’s ridiculous.’

‘It could be good for business.’

‘We sell it for that and we won’t have a business.’

Tom was silent. Priscilla said more firmly, ‘That is not going to happen.’

Tom looked at his wife. He remembered how much more relaxed he’d become after she started working with him six years ago. She had her finger on every dollar, and she was good at it. The business was doing well in large part because of her. More importantly, he trusted her more than anyone.

But little of that mattered today. Today he wanted her to be flexible.

‘I just have a feeling about this,’ he said to her.

‘You sell it for fifteen thousand and we make no profit.’

At that moment Tom Van Gundy realised he was willing to let go of any profit. In part, he didn’t want to disappoint so many women. It was the same feeling he’d had when he played football in high school and didn’t want to disappoint the fans. He knew that turning away twelve women wouldn’t be good business either. Deep down inside, though, he wanted to see Priscilla smile the way these women were smiling. Six months earlier her sister Doreen had died of cancer and he hadn’t seen her smile wholeheartedly since then.

Something more important was happening here than making money, something so important that it gave him an idea.

Tom Van Gundy rarely acted without his wife’s consent, and he knew if he continued to debate the issue with her, he’d lose. Deciding that it was better to plead forgiveness afterwards than ask permission before, he decided to deal with the repercussions later. He walked out of the back room to hand Jonell the sheet of paper on which he’d scribbled fifteen thousand.

‘I’ll give it to you for this price,’ he said, ‘but on one condition. I want you to let my wife be in your group.’ He had no idea how Priscilla would feel about it or if she’d even participate. He just knew he wanted these women in her life.

Jonell looked at the attractive, soft-spoken man in front of her. She didn’t know why he wanted his wife in the group, nor did she know who his wife was or if she’d like her or if any of the women she’d recruited would like her. But the whole idea was about inclusion and sharing, so she didn’t hesitate.

‘It’s a deal,’ she said.

Jonell wasn’t worried about Tom’s wife. She was worried that the women she’d worked so doggedly to recruit would balk at paying nearly two hundred dollars extra each. Then what was she going to do? She hid her concern behind her most radiant smile of the day.

Tom returned to the back room.

‘I gave it to them for fifteen thousand,’ he said, again to her bowed head, ‘but you get to be in the group.’

Priscilla looked up at him. ‘What are you talking about?’

‘The group of women. You get to be part of it.’

She knew that he felt concerned about dropping the price, so her tetchy retorts stayed in her head. Had he lost his mind? Had he forgotten that the shopping centre takes 7 per cent and the salesman a 3 per cent commission? They wouldn’t even cover their costs. She was always the bulldog, he the golden retriever. Nothing ever changed. But what was the point of arguing? It was a done deal.

‘Whatever,’ she said. And that was all she said.

Priscilla stayed in the back room. She had no curiosity about the women. She had no interest in being part of the group. She had no interest in owning a necklace she could have borrowed any time she wanted anyway. All she could think was that if her husband kept making deals like this they’d be out of business. She went back to the books to try to work out a way to make up for the day’s losses.

But Tom Van Gundy saw something his wife didn’t. He saw a group of women unlike any others he’d come across in his twenty-seven years of selling to women, talking to women, understanding women. He saw a collective vitality, an unexpected opportunity. He saw possibility.

Possibility was what Jonell’s vision was all about. It wasn’t about a necklace as an accessory. It wasn’t about diamonds as status or investment. It was about a necklace as a social experiment. A way to bring women together to see what would happen. Could the necklace become greater than the sum of its links, thirteen voices stronger than one?

Jonell’s confidence wasn’t misplaced. By the time her Visa bill arrived three weeks later, she’d found the final four investors she needed. Apart from the jeweller’s disgruntled wife, there were old friends, new friends and friends of friends. Their ages ranged between fifty and sixty-two so all but one qualified as part of that eclectic generation known as the ‘baby boomers’. One of them had been married and faithful to one man for thirty-plus years, while another had had three husbands and dozens of lovers, and some were single but dating. Some were childless while the rest had up to four children, of ages ranging from ten to grown-up. There were doting grandmothers, card-carrying conservatives and lifelong liberals. Some had advanced degrees, others high school diplomas. They had stuck to one career or jumped from job to job, and they worked in finance and farming, medicine and teaching, business and property, media and law. Some came from wealthy families and others were completely self-made. They were Catholic and Jewish, feminist and traditionalist, blonde and grey-haired.

No woman said yes to Jonell’s proposition just because she was interested in jewellery or diamonds. No woman said yes to the necklace because she lusted to wear it. Some wrote a cheque without even seeing it. Each bought a share because, as Tom sensed intuitively, it represented possibility.

What the women didn’t know was that over the next few years the necklace would animate their lives in ways they could never have imagined. More importantly, it would start a conversation. About materialism and conspicuous consumption, ownership and non-attachment. About what it means today to be a woman in her fifties, potentially looking at another thirty to forty years of life. About the connections we make and the legacies we leave.

This is the story of a necklace but it isn’t the story of a string of stones. It’s the story of thirteen women who transformed a symbol of exclusivity into a symbol of inclusivity and, in the process, remapped the journey through the second half of their lives.

CHAPTER TWO Patti Channer, the shopping queen

Rethinking her love of possessions