Полная версия

The Man Who Created the Middle East: A Story of Empire, Conflict and the Sykes-Picot Agreement

Cross-examined by Mr Walton, Tatton caused much amusement by asking if his lawyers could ‘refresh his memory’ about the details of the alleged Monte Carlo forgeries. So great in fact was the laughter when Mr Walton said ‘No!’, that Lord Russell had to threaten to empty the courtroom. Walton then did his best to try and show that Tatton really had very little memory of what he had signed and what he had not, but he could not sway him from the basic fact that when it came to the Jay notes, he was adamant that he had nothing to do with them. The copies he had made earlier of the 2 January letter were then shown to the jury, Tatton complaining that the pens he had had to write with were too thin. When Mr Walton said that that was because the original was written with a quill pen, Tatton stated, ‘Well, I have not used a quill pen for 40 years,’24 leaving his interrogator floundering.

Mr Walton, who saw his case collapsing, now revealed that Mark was in court, and, though he realized that ‘it was a painful thing to ask him to give evidence on the one side or the other’,25 he invited Lord Russell to call him onto the stand so that he might be questioned as to the veracity of these dates. This the Lord Chief Justice refused to do, though he told him that he could do so himself if he so wished. Though at first Walton decided against this course of action, on the morning of the following day, destined to be the last of the trial, he changed his mind.

It was a devastating experience for Mark to be forced into the witness box to testify that one of his parents was a liar, and, as Sir Edward Clarke told the jury in his summing up, his evidence was so vague and therefore so inconclusive that he might have been spared the ordeal. It was given in a barely audible whisper. In his final address, Sir Edward gave no quarter to Jessie, whom he described as a woman of ‘discreditable character’, for whom there could be ‘no sympathy and perhaps no credence’. When it came to the turn of the counsel for the plaintiff, Mr Walton accused Tatton of being a man without honour. ‘The disaster of victory,’ he told the jury, ‘would be infinitely greater than the disaster of defeat. To himself, if he won the case, there would be the degradation of the wife of twenty five years, to Mr Mark Sykes the dishonour of his mother, and to Lady Sykes, it might be, other proceedings in a criminal court. At present Sir Tatton might wish to win this case, but in the evening of his days would he wish his name to be clouded with the dishonour of his wife?’26

In the end the jury took only forty-five minutes to decide that ‘The letter of 2 January, 1897, was not in the hand of Sir Tatton Sykes.’ As the newspapers were quick to point out, this verdict left Jessie in an unenviable position. ‘The person upon whom the verdict of the jury fell with such crushing force last week,’ commented The World, ‘stands arraigned by that verdict, on a double charge of forgery and perjury; and any shrinking from the natural sequel of such arraignment will certainly be interpreted as a sign of partiality in the administration of justice.’27 Luckily for Jessie, there was never any criminal prosecution brought against her, because of the problems arising from the fact that the main witness against her would have been her husband. The horrendous publicity was punishment enough, and the fact that public sympathy lay with Tatton. ‘Sir Tatton Sykes may not have been the most judicious of men in the management of his household,’ commented the Times’ Leader of 19 January, ‘but if his evidence is to be believed, as the jury believed it, he has shown great forbearance for a long time.’28 A few days later Sydney Bowles wrote in her diary, ‘The verdict in the Sykes case was for Sir Tatton, which has hit Lady Sykes and Mark very hard. The latter told George he is not ever going to speak to or see his father again, and he will never go to Sledmere again so long as Sir Tatton lives.’29

Chapter 3

Through Five Turkish Provinces

Devastated by the outcome of the trial, and simmering with anger, Mark made plans to travel abroad for a few months. He needed to get away from the lawyers, a profession he would despise for the rest of his life, and to put as much distance as possible between himself and his parents. His education had suffered from the stress of the trial, the result being that he had failed the ‘Little-Go’ exam that all Cambridge students were required to take in their second year. Luckily for him, the Rev. Swain attached little importance to this. ‘He could have taken the ordinary degree easily enough,’ he noted, ‘if he had set himself to do it, but it never seemed to him worth doing. He seemed to be always looking round the University to see how it might best serve him, and to follow his own conclusions without considering the views of other people or whether his practice were usual or unusual. He seemed to me to do this with great sagacity … The power of close application to what did not immediately interest him, if he ever had it, was lost before he appeared at Cambridge.’1

His plan, supported by his tutors, who understood how much both he and they would get out of the trip, was to return to Palestine and Syria, scene of many of his childhood travels. With the help of A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine, first published in 1858 by the London publishers John Murray, he mapped out a journey that would take him as far east of the river Jordan as was possible, before striking north to Damascus through the remote and mountainous Druse country of the Haurân. In preparation he also persuaded the distinguished lecturer in Persian Professor Edward Granville Browne to give him some basic instruction in Arabic, and though Mark was soon reporting to Henry Cholmondeley that his lessons were progressing well, Browne let it be known that he considered his new pupil to have ‘the greatest capacity for not learning he had ever met!’2 Unfortunately for Mark, scarcely was he set to leave for the East than his mother got wind of his intentions and tried to attach conditions to her parental blessing. ‘I forgot to tell you,’ he wrote from Cambridge to his first cousin, Henry Cholmondeley, the Sledmere agent, ‘… my mother was quite willing for me to go if I took the maid and herself with me, which is of course ridiculous’. Barely concealing his anger he added, ‘The only object of having me here is to come down and extort a few shillings or pounds as the case may be, to read all the letters she may find in the rooms and return to London …’3

He left without her, accompanied only by his servant, McEwen, travelling first to Paris, and from there taking the Orient Express to Constantinople, a journey of three and a half days. He arrived at the Pera Palace Hotel, however, only to find three telegrams from his mother that had reached there before him.

(1) Return at once important.

(2) Must return at once father will not settle.

(3) Absolutely necessary your return will explain on arrival.

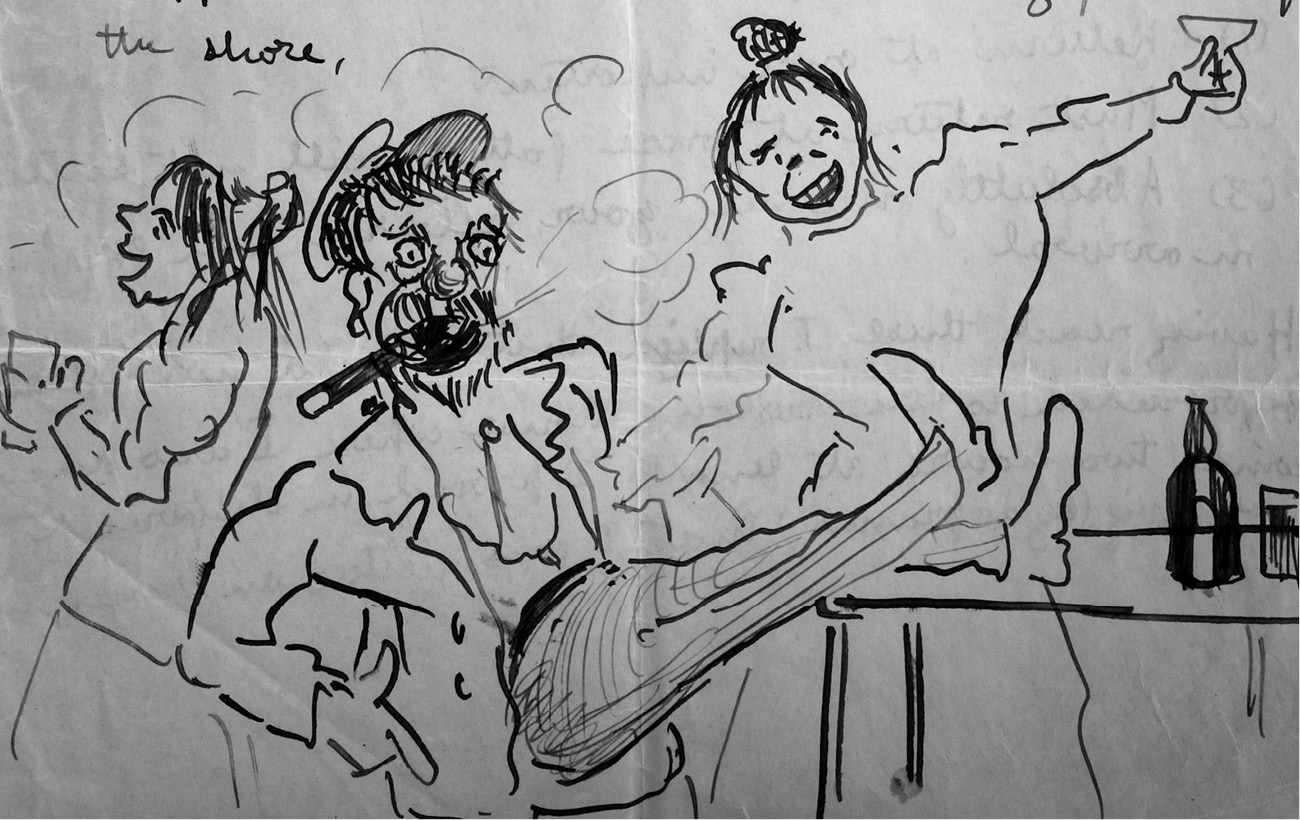

‘Having read these,’ he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley, ‘I replied that I could not return and proceeded to the Custom House where I was delayed some two hours. At length I proved in different ways viz (by 20 francs) that I was neither an Armenian travelling on a forged passeporte [sic], or an English conspirator or an importer of Dynamite …’ He then boarded a Russian steamer bound for Jaffa, carrying 800 Russian pilgrims in the hold: ‘when I went into the hovel that does duty for a Saloon,’ he told Cholmondeley, ‘I found the Russian Skipper blind drunk with two lady friends from the shore’.

He did not, he continued, expect it to be ‘a pleasant voyage as I am the only other passenger’.4

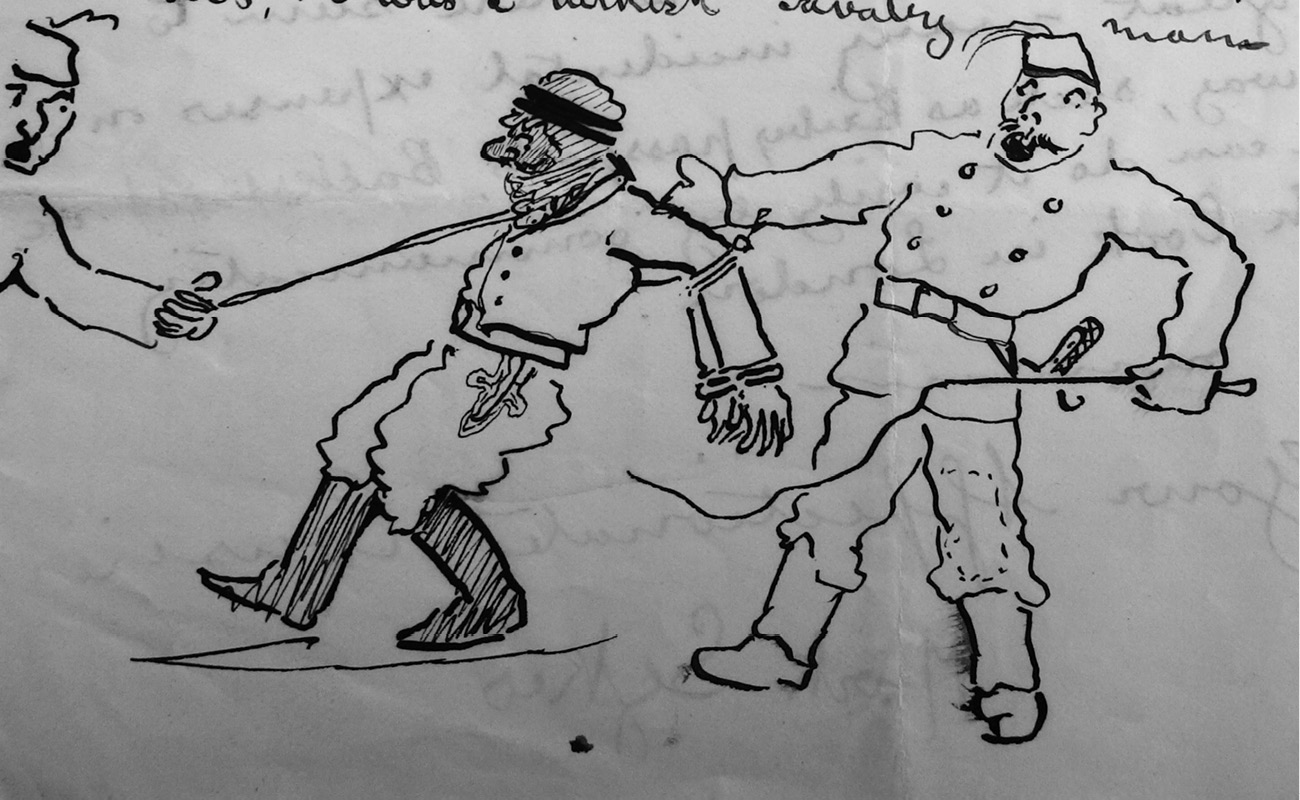

On arrival in Jaffa Mark took the daily train to Jerusalem, operated by the French company Société du Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa à Jérusalem et Prolongements. It was an uneventful journey, bar one incident, which both amused and impressed him: ‘when the train reached a station called Ramleh,’ he reported to Cholmondeley, ‘a shot was fired, and presently a man appeared tied up like this (drawing),

he was a Turkish cavalryman. It turned out that he had had a quarrel with a farmer two years ago, he had been looking for him ever since, found out where he was, obtained leave to go to Ramleh and shot him in the station. He then gave himself up saying he had done what he wanted and they might do what they liked.’5

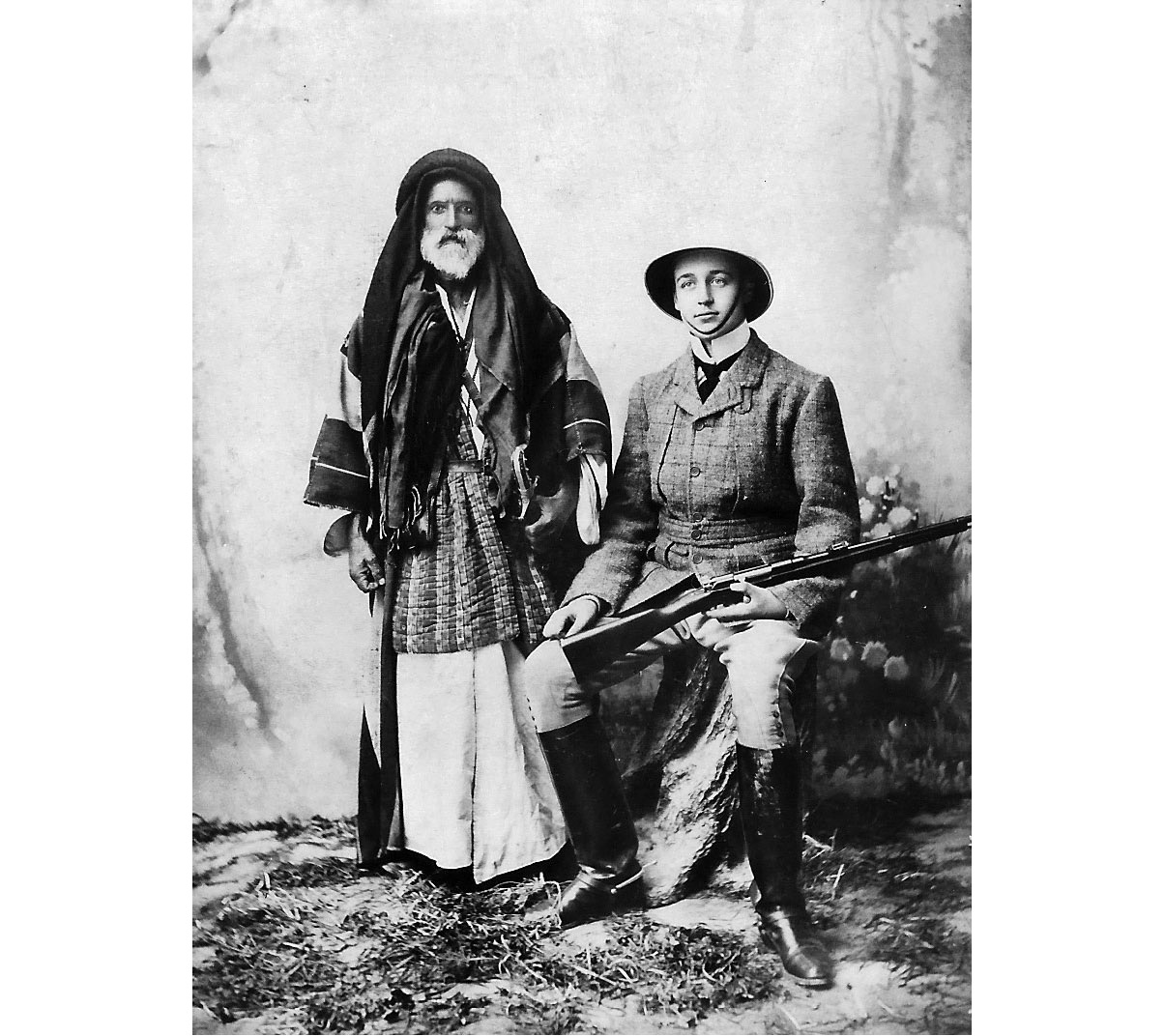

In Jerusalem, Mark was greeted by an old friend, Sheik Fellah, a Bedouin of the Adwan Tribe in Ottoman Syria, whom he had previously met on his travels with his father: ‘the old Sheikh recognized me,’ he told Cholmondeley, ‘and shouted to the crowd that I was his son’.6

They then set off north-east for Jericho, close to the river Jordan, where on 10 March they picked up the rest of the party, consisting of a dragoman, the traditional Ottoman guide, a cook, a native servant, five muleteers and an Armenian photographer who was to spend one day with them photographing Sheikh Fellah’s camp at El Hammam. ‘The people were wild and interesting,’ wrote Mark. ‘The Arabs, every man of whom carried a weapon of some sort, struck terror into the heart of the Armenian. They dug him in the ribs with a pistol, whereat he wept, upset his camera, and remembered he had pressing business at Jericho. He wanted to return at once, but I persuaded him to take four photographs.’7

Sheikh Fellah’s nephew, Sheikh ‘Ali, invited them for lunch. ‘The food consisted of a huge bowl of meat and rice,’ Mark recorded, ‘into which I and another guest, who was a holy dervish, first dipped our hands. The holy man showed no dislike to eating with so ill-omened a kafir as myself, but told my dragoman that he had known an Englishman with a long beard who spoke Arabic, had read all Arabic books and wrote night and day without eating or sleeping, and whom he had nursed at Salt during an illness. His name was Richard Burton. In return that evening I invited the two Sheikhs to dine with me. Fellah is a great friend of the Franciscans, having a room of his own in their convent in Jerusalem, and so had learnt the use of knife and fork, but ‘Ali, true son of the desert, was much puzzled by the Frankish eating tools, and invariably took the spoon from the dish for his own use.’8

Mark’s travels progressed smoothly until, on 13 March, he reached ‘Ammân, today the capital of Jordan, the site of which is described in the 1903 edition of Murray’s Handbook as being ‘weird and desolate … The place is offensive too from its filth. The abundant waters attract the vast flocks that roam over the neighbouring plains, and the deserted palaces and temples afford shelter to them during the noon-day heat; so that most of the buildings have something of the aspect and stench of an ill-kept farm-yard.’9 Here the Circassian military caused problems for Mark’s party, insisting that he did not hold the correct travel permits, and though he managed to get as far as Jerash, a ten-hour ride away, he was held up there for a number of days. On 19 March, when he was finally able to continue his journey towards the ancient biblical city of Bosrah, he was lucky enough to meet the Hajj pilgrimage on its way to Mecca, an experience that very few Westerners would then have had.

‘It was an extraordinary sight,’ he wrote, ‘… miles it seemed to be of tents of every shape and form: military bell tents; black Bedawîn tents; enormous square tabernacles of green, red, and white cloth; tiny tentes d’abri, some only being cotton sheets on poles three feet high. The gathering of people would be almost impossible to describe. In one place I saw a family of wealthy Turks in frock coats, all talking French; close by, a green-turbaned Dervish reading the Korân; a little further on, the Pasha of the Hajj, in a fur-trimmed overcoat, giving orders to a dashing young Turkish subaltern; here, two men who owned a most gorgeous palanquin which they were in hopes of letting to some rich lady from Cairo, were fighting over the fodder of the two splendid camels that carried it; there, Arab stallions were squealing and kicking at the mules of the mounted infantry contingent … There were at least 10,000 civilians in the pilgrimage. Among them were many whole families of hajis, children and women being in almost as great numbers as men … The enormous procession, at least four miles long, glittering with red, green and gold saddles and ornaments, was an impressive sight that I shall never forget; for every animal had at least four bells on its saddle or neck. I could hear it like that sound of the sea …’10

For Mark, the country of the Haurân was the most interesting part of his trip, known as it was for the number, extent and beauty of its ruins. It was the home of the Druses, a monotheistic religious and social tribe whose sheikhs formed a hereditary nobility that preserved with tenacity all the pride and state of their order. The correct letters of introduction were vital for the progress of a traveller through their lands, but once obtained they would be received with the greatest hospitality, with no requirement of compensation. ‘When I arrived at Radeimeh,’ he wrote, ‘the Sheikh was particularly hospitable, not only giving me dinner but feeding all my muleteers and servants. The sight of McEwen sitting between two Druse Sheikhs and being solemnly crammed by them with rice and bread dipped in oil and pieces of mutton was, to say the least, quaint. After … the Sheikh took my dragoman aside and told him that there was a certain place in the desert named Heberieh, where there were many arms, legs and fingers sticking in the stones.’11 No European had yet visited this strange place, which he said was a long ride away and would need an escort of at least fifteen men. ‘I decided to visit the place the next day,’ wrote Mark, ‘visions of some ancient quarry or isolated sculpture rising before me, and as there was no mention of anything of the sort in Murrays Handbook, I had great hopes of making a discovery.’12

At four the following morning, the party set off and after two hours’ riding found themselves in country which Mark described as being some of the most extraordinary he had ever seen in the course of his extensive travels in four continents. He wrote of it as ‘a fireless hell; nothing else could look so horrible as that place. Enormous blocks of black shining stones were lying in every direction; in places we passed great ridges some 20 feet high and split down the centre. One of these stretched over a mile and looked like a gigantic railway cutting. There was neither a living thing in sight, nor the least scrub to relieve the eye from the monotony of the slippery black rocks. My dragoman said to me “I tink one devil he live here.”’ After four hours’ hard riding through this inferno, the party reached an open space in the centre of which was a hill. The Druses announced that they had reached their destination.

‘At first I thought the hill was only a mass of lava and sand,’ Mark wrote in his report, ‘but on closer examination I found that it was a huge mass of bones and lava caked with bones. It was infested with snakes; I myself saw four gliding through the bones. When I had taken some photographs and secured some specimens of the rock and bones, we started on our return … I can say on excellent authority that I am the first European who has visited this place.’13 When Mark eventually submitted his findings to the Palestine Exploration Fund, they concluded that the bones were probably the remains of a herd of domestic animals that had been caught in a volcanic eruption.

To have travelled to places where few Westerners have ever set foot and to have made a ‘discovery’ must have seemed the greatest of excitements for a young man of twenty, and it was undoubtedly one of the catalysts that gave Mark a life-long fascination with what would come to be generally known as the Middle East. He returned to Cambridge with a large supply of Turkish cigarettes, a Damascus pariah dog named Gneiss, an assorted array of Oriental headgear and a desire to share his experiences with anyone who would join him in his rooms, usually sitting cross-legged on the floor puffing away at a hookah. He lectured to the Fisher Society, and to the Cambridge Society of Antiquaries, as well as writing up an account of his travels for the Palestine Exploration Fund. He was planning his next trip when he received an important letter. ‘I have just heard from the Royal Geographical Society,’ he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley in the autumn, ‘to tell me that my discovery in Syria is of the greatest importance. My tutor has in consequence given me leave to stay down next term if I go abroad. I have every reason to believe that I shall find some extraordinary things in the Safah, the place where I discovered the “Hill of Bones”. I am the first person who ever entered the place. This was merely because for some reason the natives like me.’14

Mark was in high spirits when around this time he received an invitation to lunch at Howes Close, the Cambridge home on the Huntingdon Road of the local Conservative MP, Sir John Eldon Gorst. Gorst, who served as Vice-Chairman of the Education Committee in Lord Salisbury’s government, was the father of Jessie’s former lover, Jack, as well as another son, Harold, and five daughters, Constance, Edith, Eva, Gwendolyn and Hylda. This large and affectionate family welcomed in Mark, who, as an only child, was quite unused to the warm and friendly atmosphere they generated with their in-jokes and humorous banter, but he quickly fell under their spell. He too entranced them, regaling them with tales of his adventures, acting the part of the individual characters in each story.

Sunday lunch at Howes Close became a regular outing for Mark, not least because he found himself increasingly attracted to Edith, the middle of the five girls. Twenty-six years old, tall and handsome, with soft features and thick chestnut-coloured hair, she was, like him, a convert to Roman Catholicism, and their mutual devotion to their religion became the basis for, first, a firm friendship, and then a growing attraction. She was also an accomplished horsewoman and since Mark also had a horse stabled in Cambridge, they took to going riding together. After the intrigues and machinations of his mother, Edith’s down-to-earth approach to life came like a breath of fresh air. ‘I really like [you],’ he told her, ‘really and truly and not in any way tinged with that ridiculous, maudlin, drivelling, perverse folly that idiots call “being in love”. I like you because you are honest and unselfish, because you are the only truly straightforward person I have ever met.’15

Edith’s emotional support was doubly important in the light of his mother’s situation. She was at her lowest ebb. Her friends had all dropped her. She could not approach her brothers, who were all respectably married with families, while her younger sister Venetia, married to an American millionaire, Arthur James, and one of Society’s leading hostesses, considered that she had disgraced herself beyond measure and would have nothing to do with her. She had been turned out of the house in Grosvenor Street and, to cap it all, in December 1898 she suffered the death of her beloved brother-in-law, Christopher, who had been one of the few people to stand by her through all her troubles. Mark decided that before he left on his next journey, he would make one more effort to persuade his father and his lawyers to reach a final settlement with Jessie. ‘Dear Cousin Henry,’ he wrote to Cholmondeley, ‘… would you try & get a meeting arranged between yourself, my father, Gardener [sic] and I at Gardner’s [sic] office, this is the last chance of a settlement, & worth trying, my mother is really broken and would accept any reasonable terms. I hope I can trust you to arrange this meeting as after that I should feel quite unresponsible for any further disgraces & that I had done all possible to stop it …’16

Confident that he had set the wheels in motion to try and help his mother, he prepared to set out for Syria. On the eve of his departure he went to mass in Cambridge to take one last look at Edith, an event which reinforced his feelings for her. ‘If you knew the agony of mind I went through,’ he wrote to her on his return, ‘… when I saw you leave the church and I went away without a word, if you knew how I felt that day, how I shook as if with an ague, with dry mouth and trembling steps, how I watched you go away further and further, and by quickening my steps I could have caught you up and didn’t for fear that you might have some small inkling what was in my mind before I chose you should, because I thought to myself, perhaps I am only in love …’17

Mark left for Syria on 14 December, intending to return to the Haurân in the hope of making more discoveries, but things did not work out quite the way he had hoped. The country was divided into three districts, or Wilayets: Aleppo in the north, Beirut in the west and south, and Damascus, which embraced the whole country east of the river Jordan. Each of these was governed by a Wâli, and was in turn divided into districts which themselves were governed by more officials. No progress could be made by the traveller without a series of permissions, the issue of which was by no means certain, often leading to days or even weeks of delays. For some reason, ‘difficulties arose’ and Mark was refused a permit by Nazim Pasha, the Wâli of Damascus, to visit the Haurân. Instead, he decided to travel to Baghdad by way of Aleppo.

The party left Damascus on 17 January. ‘I took with me,’ wrote Mark, ‘a dragoman, a cook, a waiter, four muleteers, and a groom; seven Syrian mules … two good country horses for myself and one each for the cook and the waiter; a Persian pony for the dragoman; and last, though not least, a Kurdish sheepdog that answered to the name of Barud, i.e Gunpowder, and not only attended the pitching and striking of the camp but after nightfall undertook the entire responsibility of guarding it.’18 Of the attendants, including Michael Sala, the cook, and Jacob Arab, the waiter, by far the most important was the dragoman, a Cypriot Christian called Isá Kubrusli, whose job was to act as interpreter and guide. A striking-looking man with piercing eyes, he had worked as a dragoman for forty years, in which time he had served a number of important Englishmen, notably Sir Charles Wilson on his expedition to locate Mount Sinai in 1865, and Frederick Thesiger in the Abyssinian Campaign of 1867–8, ‘Thirty years ago,’ Mark wrote, ‘a dragoman was a person of importance; a man similar in character to the confidential courier who in the last century accompanied young noblemen on the Grand Tour. But he has degenerated and for the most part is now simply a bear leader, to hoards [sic] of English and Americans who invade Syria during the touring season.’19

Isá, who worked for the Jerusalem office of Thomas Cook, had a very poor opinion of most of his clients. Unlike the rich and cultured gentlemen he had encountered in the old days, who wore beards, could ride and shoot beautifully, and were liberal with ‘baksheesh’, ‘Now everything very different,’ he used to say. ‘Many very fat and wear rubbish clotheses; many very old men; many very meselable; some ride like monkeys; and some I see afraid from the horses. Den noder kind of Henglish he not believe notin; he laugh for everything and everybody; he call us poor meselable black; he say everything is nonsense and was no God and notin …’20

In the first week of their journey, the weather deteriorated by the day, with constant rain and hail storms, and eventually turning to snow, which got heavier and heavier until ‘the weather was too cold for camping, so I telegraphed to Damascus for a carriage to take me to Aleppo’. Eventually an ‘antique monstrosity’ arrived, drawn by four horses abreast. It was ‘enormously broad, with a rumble for baggage behind’ and ‘had the appearance of a decayed bandbox on a brewer’s dray; and, as I found to my cost, was extraordinarily uncomfortable’.21 Their first stop was at the village of Hasieh, ‘the most desolate and filthy little village that it has ever been my luck to visit’. The guest house consisted ‘of a large heap of offal with four rooms leading off it: the first and best was occupied by the cow; the second which was not quite so clean, was given to me; in the other two most of the villagers were gathered together to watch my cook preparing what he called “roast whale and potted hyæna”, that is roast veal and potted ham’.22