Полная версия

The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols: The Ultimate A–Z Guide from Alchemy to the Zodiac

11. MASONIC APRON

The humble apron of the working Mason is elevated to almost religious status by the Freemasons. Generally made of leather, the way the apron is worn symbolizes the status of its wearer, with the bib worn up for the apprentice, or down by superior grades. Wearing the apron is representative of work and the necessity to be busy and industrious, and also of the fig leaves worn by Adam and Eve; as such the apron preserves the modesty of the wearer. Like the tracing board, the Masonic apron has the signs and symbols of the Craft embroidered on it.

One of the most famous of the many Masonic aprons is that which belonged to George Washington. Given to him in 1784 by the Marquis de Lafeyette whose wife embroidered the apron, it displays many Masonic symbols. Nothing is left to chance; the border colors of red, white, and blue are not only the national colors of France but also of the USA. Other symbols on this historic apron include:

the All Seeing Eye—

watchfulness, the Supreme Being;

rays—show the power of the Supreme Being to reach inside the hearts of men;

rainbow—symbolic of the arch of Solomon’s Temple that is supported by the two pillars, Jachim and Boaz;

Moon—the female principle;

globes on top of pillars—peace and plenty;

the three tapers—symbolize the three stages of the Sun; rising in the East, in the Southern sky at noon, and setting in the West;

trowel—symbolic of spreading love and affection, the “cement” that binds the Brothers of Freemasonry;

five-pointed star—represents friendship;

checkered pavement—often a feature of temples and again is based on the floor of Solomon’s original temple and represents the duality of opposites, male and female, and so on;

steps—represent the degrees of masonry;

coffin—represents death and therefore rebirth and is a recurrent motif in Freemasonry;

skull and crossbones—symbols of mortality but also of rebirth;

acacia;

compasses;

the square and level;

the ark—safety and refuge;

tassel and knot—the ties that bind the Brothers;

the Sun—the Light of God, the male principle;

sword and heart—symbolic of justice being done; nothing can be hidden from the eyes of the Great Architect;

seven six-pointed stars—here, seven stands for the seven liberal arts and sciences;

beehive—a symbol of industry and a reminder that man should be rational and industrious at the same time.

12. 47th PROBLEM OF EUCLID, ALSO KNOWN AS THE BRIDE’S CHAIR

This mathematical theorem has been called one of the foundations of Freemasonry. It is called the 47th Problem for no more esoteric reason than Euclid published a book of theorems, of which this was number 47.

Its significance within Freemasonry is somewhat nebulous. However, the beginnings of the Fellowship in architecture and construction, and the usefulness of the 47th Problem as a measuring device, might give us the answer. The design features in Masonic regalia including lodge decorations and Masonic “jewels.”

The 47th Problem is also called the Egyptian string trick, and a practical demonstration in making of the shape illustrates its efficacy perfectly. Take a piece of string and tie 12 knots at exact intervals along the string. Then join the ends of the string, again making sure that the knots are evenly spaced. Hammer a stick into the ground. Put one of the knots over the stick. Stretch three divisions of knots and sink another stick into the ground at the point of the third knot. Then take a third stick and skewer it into the ground at the point where a fourth knot falls. This gives a triangle in the proportions of three, four and five, and further, the lines of the string can be extrapolated to make three squares of 9 parts, 16 parts, and 25 parts.

This simple device enabled the Egyptians to remeasure their fields after the Nile flooded every few years, washing away the boundary markers. The Egyptian string trick results in a perfect right angle, an essential device in the construction of a building, and as essential today as it was thousands of years ago, although methods of constructing the angle may have changed. Pythagoras traveled to Egypt and may have discovered it there, or he may have discovered it alone. Whatever the case, it is this geometrical solution that caused him to shout “Eureka.” In addition, it is said that 100 bulls were sacrificed in honor of the importance of this seemingly simple discovery, indubitably one of the secrets that was part of the hidden knowledge of the Master Mason; it may well have been one of the pieces of information for which Hiram Abiff was murdered.

13. ASHLAR

In material terms, ashlar is the rough stone that comes straight from the quarry. In philosophical terms, to the Freemason, ashlar symbolizes the rough and imperfect state of man before he is rendered smooth and perfect in his ideally realized state. It relates to the alchemical idea of base matter that can be perfected through intellectual and spiritual realization.

14. POINT WITHIN THE CIRCLE

A seemingly simple symbol, the circle with a dot at its very center is a sign of birth and resurrection dating back to Egyptian times when it was used as an emblem of the Sun God, Ra. The symbol is associated particularly with the days of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, which fall on the summer and winter solstices respectively.

15. THE TEMPLE FLOOR

Although it is stated time and time again that the symbols inherent within Freemasonry are nondog-matic and are as such open to interpretation, it is safe to say that the features of the actual temple form an important part of the secret signs of the Craft. The floor of the temple is no exception.

It is constructed of checkered tiles of black and white. These colors represent the duality of opposites; night and day, dark and light, male and female, fire and water, Earth and air, and all the other manifestations of this concept. In

Ancient Egypt, the colors were used as a reminder of the need to unify spirit and matter.

16. GAOTU

Abbreviated words, initials, and acronyms form a large part of Masonic ritual, since the pronunciation of certain words is believed to dilute their power and abbreviations are used instead. The abbreviation of GAOTU stands for Great Architect of the Universe, which in turn refers to God. Here there is a parallel to the nature of God as the builder or designer of the macrocosm, and the role of the Freemason as the designer of the microcosm.

GUNGNIR

This is the magical weapon known as Odin’s Spear or Javelin. Like Mjolnir, the magical hammer belonging to Odin, Gungnir—whose name means “The Unwavering One”—has two very practical qualities that render it an essential tool in the arsenal of the powerful thunder god; it always hit its mark, and it always returns, like a boomerang, back to the thrower. As well as being a sacred object, there is a runic symbol, Gar, that also represents the Gungnir.

HALO

The halo, aureole, or aura all refer to an emanation of light, generally depicted appearing around the head. The halo is a symbol of spiritual sanctity or of divine grace, used in Christian iconography, for example, in pictures of saints. Although the halo is the sign that a person is blessed by the Divine, some people claim that they can actually see this phenomenon, and that the many colors of the aura that surrounds the entire body can be used as a diagnostic tool.

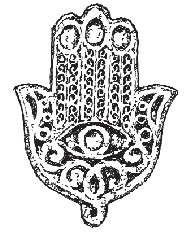

HAND OF FATIMA

Also known as the Khamsa, the Hand of Fatima is named for Fatima Zahra, the daughter of Mohammed. It is a very ancient symbol, often used as a talisman, and in the Middle East it is ubiquitous, appearing in houses, shops, in taxis, and hotels. The hand is not really shaped like a normal human hand, but has two balanced thumbs and no little finger. The eye in its palm wards off the evil eye, so the Hand of Fatima is a double symbol of protection since the palm, held up, is a forbidding gesture. Khamsa actually means “five” and has relevance for both Muslims and Jews. Peace activists have adopted the Hand of Fatima in recent years; a reminder that the two faiths have many commonly shared beliefs.

HAND OF GLORY

If magical charms have more efficacy the harder they are to construct or come by, then the Hand of Glory must be powerful indeed. Noticeably absent from New Age emporia, the Hand of Glory was popular with thieves during the sixteenth century. It was a light, or candle, made from the severed hand of a hanged convict. After this grisly relic was mummified by being embalmed in oils and special herbs, it was turned into a candle using tallow also made from a hanged corpse.

The Hand of Glory was the favored tool of thieves because, once alight, it was said to render household members unconscious. Therefore the thief could go about his nefarious activities undisturbed.

HEX SYMBOLS

In the south-eastern part of Pennsylvania lives a population of European settlers, primarily from the Rhine area. These people come from different religious communities including Lutheran, Moravian, Quakers, Mennonites, and others. Some of these groups, despite their deeply held religious beliefs, are united by one thing; a thriving belief in witchcraft, also known as Hexerie, from the German, Hexe, meaning “witch.”

Despite their godliness, these are a very superstitious people. One of the popularly held beliefs is that a cross, drawn on the door-latch, will prevent the Devil from entering the house.

HERALDRY

The symbols and signs of heraldry act as a sort of historical shorthand, encoding the attributes of the families to whom the heraldic crests belong. The various coats of arms, still in use today, originated in the need to be able to identify opposing armies and single combatants. This necessity dates back to the time of hand-to-hand combat, almost 1000 years ago, although soldiers of much earlier times painted images on their shields that held significance for them, personally, as well as being a sign of identity. Although the blazes, escutcheons, badges, mottos, and crests may at first appear to be a dense forest of impenetrable symbols, their secrets can be interpreted easily. This entry does not pretend to be an exhaustive analysis of the elaborate heraldic codes, but gives a general overview of some of the most commonly used emblems.

THE GREAT SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The Great Seal that is featured on the United States dollar bill contains many heraldic attributes. Here are some features to look out for.

1. Shape—the shield versus the lozenge

Since women didn’t go to war, women’s heraldic designs are depicted on a lozenge-shaped framework (which looks like a diamond tipped onto one point), as opposed to the shield of the male. The lozenge itself, suggestive of the vesica piscis, is a feminine symbol. Although the shield shapes vary, the difference between the two shapes is easily recognizable. Similarly, members of the noncombative clergy use the lozenge or oval shape.

2. Color

The colors used within heraldry are called tinctures. There are also fields of patterns known as furs, the most common of which is called “ermine,” and resembles the fur of the ermine stoat; the other is called “vair” and comes from a variegated gray-blue colored squirrel. The names of the colors are different, too, retaining their archaic (primarily French) origins.

Gold = Or

Silver = Argent

Red = Gules

Blue = Azure

Purple = Purpure

Green = Vert

Black = Sable

In order that they may remain as clear and visible as possible, a color is rarely laid on top of another color, and the same rule applies to the metallics.

3. Divisions

The shield, or lozenge, can be divided in a number of ways. Split in half horizontally it is called “party per fess.” Vertically, it becomes “party per pale.” When it is divided diagonally from left to right, it is “party per bend.” The opposite direction gives “party per sinister.” The “field” of the lozenge or shield can also be split with a saltire cross, or a “normal” one. It can be divided by a chevron, or into three with a Y-shape. There are other variations; lines can also be wavy or curved.

4. Charges

A charge is, effectively, a picture. It can be any object, a symbol, an animal, a plant. Exotic creatures have a large part to play in heraldry; unicorns and dragons join their more realistic counterparts, boars, lions, eagles. The symbolism of these creatures is explored elsewhere in this book, but there may also be a specific link belonging to a family coat of arms, which will have passed into the annals of the family history. The Fleur de Lys has its place as the symbol of the French ruling classes, for example.

5. Crest

This is the element that rests on top of the emblem, effectively crowning it. It tends to appear above the shield, and is the symbolic counterpart of the plume of feathers that knights once wore on their helmets as a sign of distinction and recognition. Because women did not have any occasion to wear a helmet, the lozenge generally has no crest.

6. Mottoes

This is a phrase that describes the bearer of the heraldic emblem. It acts as a sort of historic mission statement; the name of the family might be used in the motto as a pun or play on words. The motto can be in any language although Latin and French are possibly the most popular.

7. Supporters

The shield or lozenge is sometimes supported, generally by animals that stand upright and appear to hold the shield. Again, these creatures bear a relevance to the owner of the heraldic device.

OTHER HERALDIC SYMBOLS

Symbols used within heraldic devices generally are concise shorthand for the qualities of its owner, and the individual meaning can be found in other parts of this book. The lion, for example, signifies valor, the fox, a wily intelligence.

Heraldic devices have meanings of their own; the “mullet,” for example, is not a fish, but a star that denotes the third son. Other curiosities include the Bezant, or gold coin, meaning that the owner can be entrusted with treasure; the escutcheon, a small shield that shows a claim to, or descent from, royalty; a talbot is a hunting hound. A martlet is a symbol of a small bird with no feet, the mark of the fourth son who will have to rely on his own resources since he will not be able to rely on an inheritance. The stirrup signifies action.

There is a whole series of magical protective symbols that the community paint or carve onto the sides of their barns or houses. Called Hex Signs or Barn Signs, these magic symbols are used for a variety of reasons, including averting evil, bringing fertility and prosperity, promoting health, and control of the weather. Many of these signs, which are individually designed, become closely interlinked with a specific family, akin to a coat of arms, and are even tooled into the leather covers of the family Bibles.

These hex symbols are beautifully decorative and use universally familiar symbols in their design, including hearts for love, stars for good luck, oak leaves and acorns for strength and growth. They also use the image of a bird called a distelfink, a type of finch that lines its nest with thistledown. This bird is particularly associated with good fortune. The “double distelfink” brings double the luck.

HEXAGRAM

See Seal of Solomon and I Ching.

HOLY GRAIL

To say that something is like searching for the Holy Grail implies that the search is for a highly treasured and elusive object that might never be found. If there is a genuine Holy Grail, like the Philosopher’s Stone, it has retained its hard-to-get status.

The Holy Grail legend has direct links with two mystical pre-Christian items; the magical cauldron of the Celtic Gods that never emptied and kept everyone satisfied, and the magical chalice that represents spiritual authority and kingship. However, received information about an actual physical Holy Grail says that it is either the cup that Christ drank from at the Last Supper or the vessel that caught his blood during his crucifixion. The sacred vessel subsequently went missing.

There is a rumor that a fragment of the true Holy Grail, known as the Nanteos Cup, is secreted somewhere in the United Kingdom, specifically in Wales. The cup, made of olivewood, is reputed to have been brought to Glastonbury by Joseph of Arimethea, where it was looked after by the monks who lived at the abbey. The Dissolution of the Monasteries in the sixteenth century, in which monasteries were abolished and their valuable property seized by the Crown, meant that the sacred relic had to be removed. It allegedly ended up at Nanteos Mansion near Aberyst-wyth. Although it is now just a small fragment of wood, water drunk from it is claimed to have healing powers. Sadly, this marvelous story currently has no forensic evidence to support it and so the Holy Grail remains true to its symbolic meaning, tantalizingly beyond our grasp, for the time being at least.

The Grail Legends of the Arthurian Tales also symbolize the quest for something beyond reach. The knights, galvanized into action to find this object of desire, soon realize that they are seeking something much more than a cup; given that the shape of the grail is a feminine symbol and a powerful emblem of the spirit, according to Jung it symbolizes “the inner wholeness for which men have always been searching.” As such, the Holy Grail has marked parallels with the Philosopher’s Stone of the alchemists, and an equally elusive nature.

HORIZONTAL LINE

See First signs: Horizontal line.

HORNED SHAMAN

This symbol has a deep resonance for many, and was first discovered in the cave paintings of Ariège in France. These paintings date back to 10,000 BC. The figure may be the precursor to Cernunnos and other antlered deities. The horned shaman is also called the Dancing Sorcerer, said to represent a shaman performing a ritual ceremony. However, this theory cannot be proven conclusively.

HORNS OF ODIN

Norse legends tell of a magical mead that was brewed from the blood of a wise God, Kvasir; to drink this mead would be to benefit from the wisdom of the God. Odin managed to find this drink, and the triple horns represent the three draughts that he drank.

The horn itself is both a masculine and phallic symbol, but because it can be used as a container, it encompasses the female aspect, too. The triple horn appears in stone carvings, over the heads of warriors, implying rewards in Valhalla, the Hall of Slain Warriors that is the home of Odin.

Today, the symbol is used as a sign of identity by followers of the Asatru faith. Asatru is a relatively modern religion that acknowledges the much more ancient pre-Christian Norse beliefs.

HORSESHOE

The horseshoe has acquired symbolic significance not because of its function, but because of its shape and the metal used to make it. It is shaped like the arc, one of the first sacred symbols that represents the vault of the Heavens. When it is “upside down” it is also shaped like the last letter of the Greek alphabet, the Omega.

Flip the horseshoe the other way up, however, and it resembles the crescent Moon, therefore invoking the protection of the Moon Goddess. The iron that the horseshoe is made from further enhances this protective quality. Iron is a protective metal, which evil entities will go out of their way to avoid. The horseshoe also looks like the yoni, further strengthening its links with the Goddess.

The horseshoe is a well-known good-luck symbol and appears on greetings cards, wedding souvenirs, and the like. People nail them up over doorways for the same reason, although there is some controversy as to which way up the horseshoe should go. One school of thought says that it should rest on its curved end to hold in the luck, which, if the horseshoe were reversed, would pour away. However, pre-Christian superstition says that the horseshoe should be positioned so that it looks like the sky, and also like the yoni.

HOURGLASS

The function of the hourglass is to mark the passing of time, as sand trickles through the narrow waist in the middle of the transparent glass container that is the same shape as a figure of eight. Therefore, the hourglass is often used as a motif to show the inevitability of death.

However, the shape of the hourglass, as well as being a visual symbol and a word used to describe the figure of a shapely woman, is a lemniscate, or infinity sign. This indicates eternity. That the hourglass can be turned upside down to start the cycle all over again makes it an optimistic symbol of rebirth.

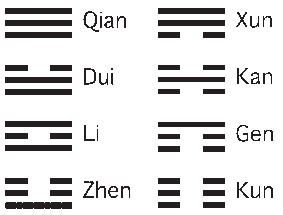

I CHING

The I Ching is an ancient Chinese system of philosophical divination, possibly dating back to the eighth century BC, which is still in use today.