Полная версия

The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols: The Ultimate A–Z Guide from Alchemy to the Zodiac

The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols

The Ultimate A-Z Guide from Alchemy to the Zodiac

Adele Nozedar

For Adam and for the seven secrets

‘In every grain of sand there lies Hidden the soil of a star’

Arthur Machen

‘I do not need a leash or a tie To lead me astray In the land where dreams lie’

Yoav

In Nature’s temple, living pillars rise Speaking sometimes in words of abstruse sense; Man walks through woods of symbols, dark and dense, Which gaze at him with fond familiar eyes.

Like distant echoes blent in the beyond In unity, in a deep darksome way, Vast as black night and vast as splendent day, Perfumes and sounds and colors correspond.

From “Correspondences,” Charles Baudelaire

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

Introduction

Part One Signs and Symbols of Magic and Mystery

Part Two Fauna

Part Three Flora

Part Four Flowers of the Underworld

Part Five Sacred Geometry and Places of Pilgrimage

Part Six Numbers

Part Seven Sacred Sounds, Secret Signs

Part Eight The Body as a Sacred Map

Part Nine Rites and Rituals, Customs and Observances

Part Ten The Nature of the Divine

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this book is to seek a true understanding of the secret signs, sacred symbols, and other indicators of the arcane, hidden world that are so thickly clustered around us. During this process, we’ll shed light on the cultural, psychological, and anthropological nature of our signs and symbols. We’ll also be surprised to discover that many of the everyday things we take for granted can hold hidden secrets, and by having the key to this knowledge we’ll gain an insight into the minds and concerns of our forbears who constructed these symbols.

NO BEGINNING, NO END: ANATOMY OF A SIMPLE SYMBOL

Rodin said, “Man never invented anything new, only discovered things.” While it’s true to say that some symbols have been man-made for a specific purpose, it’s equally accurate to argue that everything is inspired in some way by the natural world around us, by the forms of nature, plants, animals, the elements. Even a reaction against the fluid forms of nature is generally inspired by a desire to provide an alternative. Sometimes the revelation of a natural symbol is immediate; other such discoveries are the result of years of painstaking observation.

One of our simplest symbols has elaborate and arcane origins.

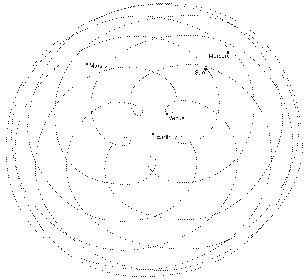

Here is a picture, not of a manmade or computer-generated pattern, but of the shape made in the sky by the Planet Venus. Venus is the only planet whose dance around the Sun in the depths of space describes such a definite and distinctive form, and we can only imagine the sense of wonder that must have been felt by the ancient Akkadians who first charted the design. They also realized that the Morning Star and the Evening Star, previously considered to be two separate celestial bodies, were one and the same. This discovery had a profound effect, which has cast such a long shadow over the archeology of symbols that we are still governed by it today. Here’s why.

Because of Venus’s proximity to the Sun, its light is often obliterated, and so it is visible only in the early morning or in the evening, either just before sunrise or just after sun-set. The Greeks called the morning star Eosphoros, “bringer of the dawn” (later, the star would be called Lucifer, the brightest of the angels cast out of the Heavens). As the Evening Star, it was called Hesperos, “star of the evening” (which gives us the name of evening prayers, or vespers).

It takes eight years and one day for the appearances of Venus to complete an entire pentagram. These days we can plot these movements relatively easily, but for our ancestors the process must have been elaborate and painstaking, as uncertain and laborious a voyage of discovery as the traversing of any great physical ocean. The Goddess that we know as Venus was, to the Akkadians, Ishtar/Inanna, divinity not only of love and harmony but also Goddess of war. Incidentally, Venus is the only major planet of our solar system, aside from the Earth itself, to be designated a feminine spirit.

The Mayans determined their calendrical system from the movements of Venus, and chose propitious positions of the planet to determine the time of a war. The five-pointed star that is still used as a military symbol—stenciled onto tanks, for example, or used in insignia—derives from the stately movement of this great astral Goddess.

Similarly, the apple given by Eve to Adam contained a hidden symbol within it; the pentagram created by the pattern of the pips. Eve offered Adam not only knowledge of the divine feminine—a holy grail indeed—but offered him a symbol of the true marriage of opposites, the feminine number two wedding to the masculine number three. Eve, therefore, personifies Ishtar/Venus/Aphrodite as the Goddess of sensual love (and Venus, incidentally, is the derivation of the word “venereal”). Further, Ishtar was demonized in the Bible as the Whore of Babylon.

So, a seemingly simple thing such as the shape made in the sky by the path of a planet can be full of complexities and contradictions, which not only clarifies some aspects of the symbol but also poses further questions. The truth is that the quest to understand the meaning of a symbol is as much a personal voyage of discovery as a collective one, and it is in the spirit of exploration that I hope you will adventure into this book.

THANKS

There are several people without whom this book would never have been written. I’d like to thank Katy Carrington, Terence Caven, Jeannine Dillon, Chris Wold, Simon Gerratt, Graham Holmes, Kate Latham, Faith Booker, and Laura Summers at HarperCollins. Charlotte Ridings, Martin Noble, and Mark Bolland were the editors. I’d also like to thank Wanda Whiteley.

Any book about symbols would be nothing without the illustrations. Paul Khera has done the bulk of these, with additional thanks to Anat Cederbaum, Myong Hwi Kim, Kruti Sanaija, and Yuki Nakamura for advice and help with some aspects of these pictures. I am also lucky enough to have Finlay Cowan contribute images to this book.

Other illustrators include David Little, Lyndall Fernie, and Kalavathi Devi. I would also like to thank Willa and Milo Seary for their drawings. Thanks are also due to Gavin and Davina Hogg, Sigorour Atlason, Caroline Danby, Tania Ahsan, Hamraz Ahsan, Carla Edgley, Judy Roland, Theo Chalmers, the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, Stuart Mitchell, and the good people of Raquetty Lodge, Hay on Wye. Most of all I have to thank starship commander Adam Fuest for putting up with my obsession about this book and my possible bouts of absent mindedness about anything else during the writing of it.

FIRST SIGNS: THE BASIC SHAPES OF SYMBOLS

There are certain elemental structures that occur repeatedly, not only as component parts of more elaborate symbols, but also with rich meanings of their own. In fact, it’s probably true to say that the simpler the symbol, the more scope there is for interpretation; ergo, the more meaningful it is and, paradoxically, the more complex it becomes. These primary shapes transcend barriers of time, geography, and cultural context, part of a universal language that goes before, and beyond, words. Don’t be fooled into thinking that these basic shapes are as self-explanatory as to need no analysis. A true understanding of what they represent can only add to the comprehension of the more elaborate shapes and symbols that follow in this section.

SPACE

The elements of a symbol are defined only by the space that is a part of its construction. Like the wind, the effect of space is gauged by its effect on the things within it or surrounding it. The concept of space, the void, is a profound part of our experience. To reach a state of “emptiness” is, for many, the ultimate spiritual experience and a way of connecting to the Absolute. When John Lennon wrote “Imagine,” whose lyrics gradually strip away the trappings of the material world, it was this idea that inspired him.

To be aware of the possibility of space within a flat, two-dimensional representation is to give that shape substance and a new kind of reality that lifts it off the page and makes it real. Space is not flat and cannot be confined by lines on a piece of paper. The page and the shape on it do not exist in isolation, but are a part of a greater cosmos. This book and you, the reader, are a part of this equation.

The concept of zero is a space. Indeed, the realization that “nothing” can be “something” marked a profound leap forward in man’s development. All creation myths begin with a Void, symbolic of potential.

Although attempts to explain the concept of space are inevitably faulty, it might help to think of a blank page. Before a mark is made upon the paper, the potential for what might appear there is so vast as to be unimaginable, a consideration which causes consternation for some artists and writers. Without this space, there is no arena for anything else to exist. This absence of any thing means that no thing is the most important symbol in the World.

DOT

A dot might seem to be an unassuming little thing, the first mark on the pristine sheet of paper. In this case, the dot is a beginning. But see what just happened there? The dot, an essential component in the structure of the sentence, closed it, making it a symbol of ending. Therefore, the dot is both an origination and a conclusion, encompassing all the possibilities of the Universe within it, a seed full of potential and a symbol of the Supreme Being. The dot is the point of creation, for example the place where the arms of the cross intersect.

The dot is also called the bindhu, which means “drop.” The bindhu is a symbol of the Absolute, marked on the forehead at the position of the third eye in the place believed to be the seat of the soul.

The presence of dots within a symbol can signify the presence of something else. A dot in the center of the Star of David marks the quintessence, or Fifth Element. It also acts as reminder of the concept of space. The decorated dots that surround the doorways of Eastern temples are not merely ornamental devices but have significance relevant to the worshippers. Dots frequently appear in this way, acting as a sort of shorthand for the tenets of a faith. In the Jain symbol, for example, the dots stand for the Three Jewels of Jainism. The dots in each half of the yin-yang symbol unify the two halves: one dot is “yin,” the other “yang.” Together they demonstrate the interdependence of opposing forces.

CIRCLE

The next logical magical symbol is the circle. Effectively an expansion of the dot, the circle represents the spirit and the cosmos. Further, the circle itself is constructed from “some thing” (the unbroken line) and “no thing” (the space inside and outside this line). Therefore, the circle unifies spirit and matter. The structure itself has great strength—think of the cylindrical shape of a lighthouse, built that way in order to withstand the fiercest attack by a stormy sea.

The physical and spiritual strength of this symbol are there because the perfect circle has no beginning and no end; it is unassailable. This power is the reason why the circle is used in magical practices such as spell-casting. The magic circle creates a fortress of psychic protection, a physical and spiritual safe haven where unwanted or uninvited entities cannot enter.

Hermes Trismegistus said of the circle:

God is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere.

Where would ancient man have seen the most important circles? Obviously, in the Sun and the Moon. As the Sun, the circle is masculine, but when it is the Moon, it is feminine. Because the passage of time is marked by the journey of the Sun, Moon and stars in orbit around our Earth, the circle is a symbol of the passage of time. In this form, it commonly appears as the wheel.

Because the circle has no divisions and no sides, it is also a symbol of equality. King Arthur’s Round Table was the perfect piece of furniture for the fellowship of Knights who were each as important as each other. Similarly, the Dalai Lama has a “circular” Council.

ARC

Perhaps the most prominent arc of the natural world appears in the elusive form of the rainbow, which primitive man saw as a bridge between the Heavens and the Earth.

As a part of a circle, the arc symbolizes potential spirit. The position of the arc is important. Upright, shaped like a cup or chalice, it implies the feminine principle, something that can contain the spirit. If the arc is inverted, then the opposite is true and it becomes a triumphal, victorious, masculine symbol. As such, the arc can take the form of an archway. The vaulted or arched shape of many holy buildings, from a great variety of different faiths, represents the vault of the Heavens. The arc shape often appears in planetary symbols.

VERTICAL LINE

Man, alone in the animal kingdom, stands upright, so the vertical line represents the physical symbol of the number One, man striving toward spirit. This simple line is the basic shape of the World Tree or Axis Mundi that connects the Heavens, the Earth and the lower regions. It is not only a basic phallic symbol but also signifies the soul that strives for union with the Divine.

The upright line tells us where we are at a precise moment; think of the big hand of the clock, vertically oriented at 12 o’clock.

HORIZONTAL LINE

The opposite of the vertical line, the horizontal line represents matter, and the forward and backward movement of time. This line also signifies the skyline or horizon and man’s place on the Earth.

CROSS

Here, the vertical and horizontal lines come together to create a new symbol—the cross. There are of course countless different types of cross, a few of which are covered in this section of the book. Despite any embellishments or devices, however, the basic meaning of the cross stays the same.

The earliest example of the cross comes from Crete and dates back to the fifteenth century BC although the sign is much older than this, ancient beyond proper reckoning. It is an incredibly versatile and useful sign with many interpretations. As the convergence of the vertical and horizontal lines, it symbolizes the union of the material and the spiritual (think of the sign of the cross given by Catholic priests). As a geometric tool, it has no equal; if you put the cross inside the circle, then you are able to divide the circle equally. Similarly, the cross is said to “give birth to” the square.

Because of its four cardinal points, the cross represents the elements and the directions.

In the West the cross equates with the number 4, but in China, it is associated with the number 5 since the “dot” in the middle of the cross, where the two arms intersect, is also included.

The cross is sometimes disguised as another symbol, such as a four-petaled flower. All over the world, the cross is a symbol of protection.

SQUARE

Said to be the first shape invented by Man, the square represents the created Universe as opposed to the spiritual dimensions depicted by the circle.

The square represents the Earth and the four elements. Plato described the square, like the circle, as being “absolutely beautiful in itself.” Like the cross, the square is associated with the number 4. A square has four corners; to speak of the “four corners of the Earth” is something of an anomaly since the Earth is round, without corners. All the symbolism of the number 4 is encompassed within the square, and it is interesting to note that, just as the square represents the created Universe, in the Hebrew faith the Holy Name of the Creator is comprised of four letters.

The square gives man a safe, static reference point, and a stable, unmoving shape as opposed to the continual motion of the circle.

Temples and holy buildings are often built in the form of a square, solidly designed to align with the four points of the compass. The Ka’aba at Mecca is a fine example, as is the base of the Buddhist Stupa. Altars, too, are square. Square shapes define limits and create boundaries; to speak of someone as being “square” means that they are fixed and unchangeable.

LOZENGE

A diamond shape often with rounded rather than pointed ends, the lozenge is often overlooked, but is actually a representation of the female genitalia. As such, its most popular appearance is probably as the vesica piscis, the sacred doorway through which spirit enters the world of matter. In heraldry, for example, the lozenge is used in place of the masculine shield, to denote a coat of arms belonging to a woman or a noncombative male, such as a member of the clergy.

TRIANGLE

The triangle shares all the symbolic significance of the number 3, as a shape, and therefore represents the many things that come in groups of three, from the Holy Trinity to the triple aspect of the Goddess. Triangles appear in lots of different signs and symbols. In ancient times, the triangle was considered synonymous with light, and the meanings of the triangle vary according to which way up it is. When it sits firmly on its base, then it is a masculine, virile symbol, representing fire. The other way up it becomes the water element, a chalice shape, emblematic of the feminine powers. Balanced on its point in this way the triangle also represents the yoni, further underpinning the Goddess aspect. The equilateral triangle is a harmonious form, used to indicate the Higher Powers, providing a framework, for example, for the All Seeing Eye of God.

As a symbol of strength, the triangle reinforces the corners of the square, both physically and meta-physically. The solid shape of the triangle also makes its appearance in yogic positions, for example in the Trikona Asana or Triangle Posture.

DIAGONAL

The square can be divided into two diagonal triangles. Because the length of these shapes has no simple relationship to its sides, the Greeks concluded that the diagonal must be a symbol of the irrational. Therefore, the diagonal, or oblique, has come to be associated with the incomprehensible, occult world. In J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, Diagon Alley is the hidden part of London that is a magical high street full of occult devices.

ZIG-ZAG

However it is interpreted, the jagged shape of the zig-zag carries with it the idea of heat, energy, vitality, and movement, the archetypal sign for lightning or electricity. The double zig-zag that makes the astrological glyph for Aquarius could be water or it could be the life-force itself. The serpent that spirals up the Caduceus is a soft-ened zig-zag shape. There is an inherent danger in the zig-zag, and the deities that carry it in their hands do so as a sign of their own authority and power.

Part One SIGNS AND SYMBOLS OF MAGIC AND MYSTERY

AASKOUANDY

Ironically, the first entry in this encyclopedia is a symbol that is impossible to illustrate because it takes various different forms.

An Aaskouandy charm is any object that is unusual in some way, which appears unexpectedly or is somehow out of place in its surroundings. For example, if a stone is found in the entrails of an animal that was particularly hard to hunt, then this stone is perceived to be the object that gave the animal its power, and so is eligible for Aaskouandy status.

The Iriquois believe that the Aaskouandy, a magical charm of considerable power, has a mind of its own, so much so that if it is neglected it can even turn against its owner. They also believe that the Aaskouandy has trickster ten-dencies and can change shape at will, so confusingly it may metamorphose into another object altogether.

Because the Aaskouandy is an independent being, the owner is careful to stay on the right side of it, keeping it happy with gifts and feasts.

If an Aaskouandy appears in the shape of a fish or serpent, then this is particularly potent because of the inherent power of these creatures. In this case, the Aaskouandy changes its name, too, and becomes an Onniont.

ABRAXAS

Depending on your point of view, Abraxas is either an Egyptian Sun God who was adopted by the early Christian Gnostics, or a demon from Hell who is closely associated with Lucifer, although there is a case for the former, since he was not demoted to the ranks of a demon until the Middle Ages.

Abraxas was no ordinary god, however. As Ruler of the First Heaven he had dominion over the cycles of birth, death, and resurrection.

Whatever the case, the symbol for Abraxas is a very unusual one. He has the head of a chicken, the torso of a man, and two serpents for legs. He holds a shield in one hand and a flail-like instrument in the other. The image of Abraxas was carved onto stones (called Abraxas Stones) and the stone used as a magical amulet. Occasionally Abraxas will appear driving a chariot drawn by four horses; these horses represent the elements.

This Abraxas symbol was adopted by the Knights Templar, who used it on their seals. No one knows precisely why this symbol was of particular significance, but a hidden secret within the name “Abraxas” may provide a clue.

In Greek, the 7 letters are the initials of the first 7 planets in the Solar System.

Further, if we apply numerology to the name then it adds up to 365, not only the number of days in a year but also the number of the spirits that those same early Gnostics believed were emanations from God.

Added to the mix is the speculation that the supreme magical word, “Abracadabra,” may derive from the name Abraxas, which means “harm me not.”

ADRINKA SYMBOLS

Originating in Ghana, Adrinka symbols are now related, in general, to the Ashanti people. There are hundreds of these signs, which were originally printed on the cloth that was used in sacred ceremonies and rituals, funerals in particular. “Adrinka” means “goodbye.”