Полная версия

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

The “first” gay flirtation cannot simply be overlooked and put aside as Morrison and Albin would want it to be. First of all, it had happened before. Back in Freeport during Lou’s childhood, he had indulged in circle jerks, and the gay experience left him with traits that he would develop to his advantage commercially in the near future. Foremost among them was an effeminate walk, with small, carefully taken steps that could identify him from a block away.

Despite an apparent desire originally to concentrate on a career as a writer, just as his guitar was never far from his hand, music was never far from Reed’s thoughts. Lou’s first band at Syracuse was a loosely formed folk group comprising Reed; John Gaines, a striking, tall black guy with a powerful baritone; Joe Annus, a remarkably handsome, big white guy with an equally good voice; and a great banjo player with a big Afro hairdo who looked like Art Garfunkel.

The group often played on a square of grass in the center of campus at the corner of Marshall Street and South Crouse. They also occasionally got jobs at a small bar called the Clam Shack. Lou didn’t like to sing in public because he felt uncomfortable with his voice, but he would sing his own folk songs privately to Shelley. He also played some traditional Scottish ballads based on poems by Robert Burns or Sir Walter Scott. Shelley, who would inspire Lou to write a number of great songs, was deeply moved by the beauty of his music. For her, his chord progressions were just as hypnotic and seductive as his voice. She was often moved to tears by their sensitivity.

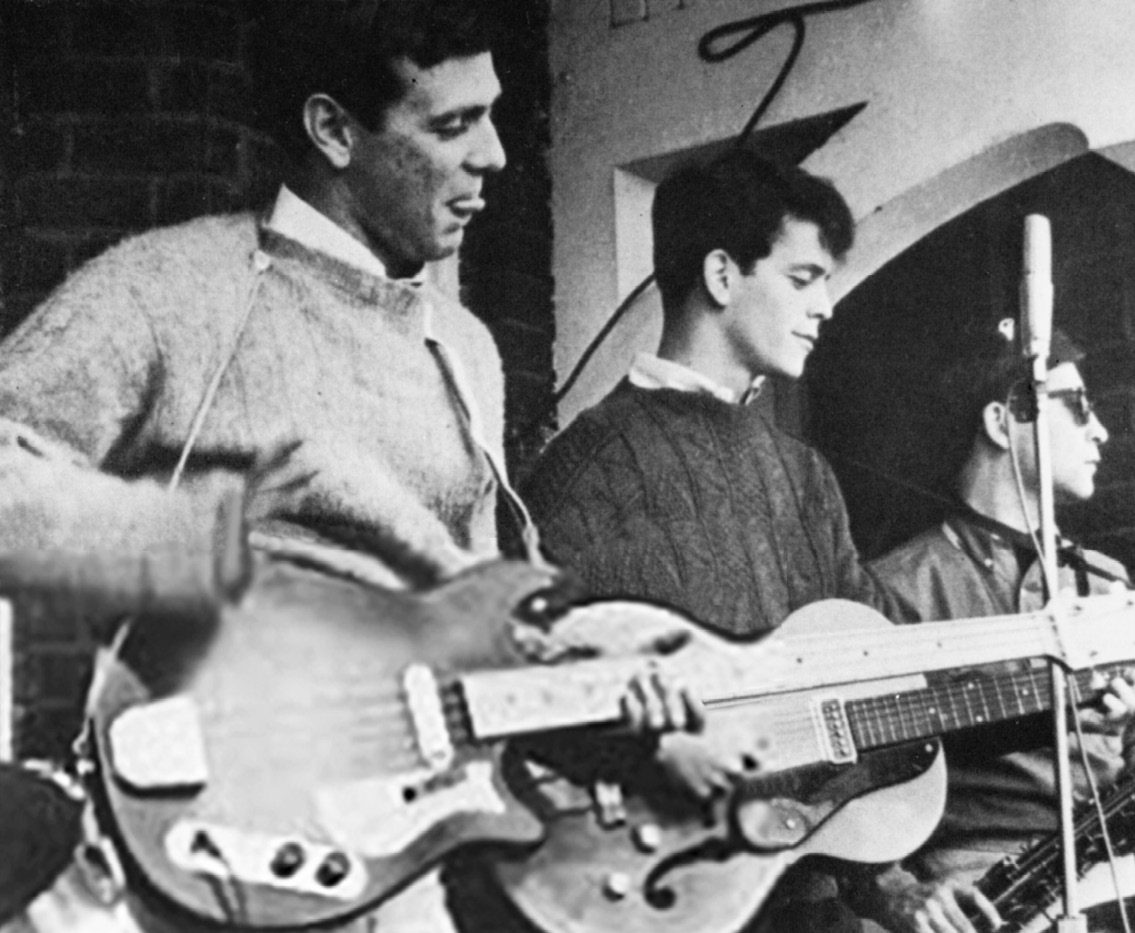

Though he was devoting himself to poetry and folk songs, Lou had not dropped his initial ambition to be a rock-and-roll star. In addition to how to direct a play, Lou also learned how to dramatize himself at every opportunity. The showmanship would come in handy when Lou hit the stage with his rock music. Reed’s development of folk music was put in the shade in his sophomore year when he finally formed his first bona fide rock-and-roll band, LA and the Eldorados. LA stood for Lewis and Allen, since Reed and Hyman were the founding members. Lou played rhythm and took the vocals, Allen was on drums, another Sammie, Richard Mishkin, was on piano and bass, and Mishkin brought in Bobby Newman on saxophone. A friend of Lou’s, Stephen Windheim, rounded out the band on lead guitar. They all got along well except for Newman, a loud, obnoxious character from the Bronx who, according to Mishkin, “didn’t give a shit about anyone.” Lou hated Bobby and was greatly relieved when he left school that semester and was replaced by another sax player, Bernie Kroll, whom Lou fondly referred to as “Kroll the troll.”

Reed playing in his Syracuse college band, LA and the Eldorados, with (left) Richard Mishkin. (Victor Bockris)

There was money to be made in the burgeoning Syracuse music scene, and the Eldorados were soon being handled by two students, Donald Schupak, who managed them, and Joe Divoli, who got them local bookings. “I had met Lou when we were freshmen,” Schupak explained. “Maybe because we were friends as freshmen, nothing developed into a problem because he could say, ‘Hey, Schupak, that’s a fucking stupid idea.’ And I’d say, ‘You’re right.’” Soon, under Schupak’s guidance and Reed’s leadership, LA and the Eldorados were working most weekends, playing frat parties, dances, bars, and clubs, making $125 a night, two or three nights a week.

Lou was strongly drawn to the musician’s lifestyle and haunts. Just off campus was the black section of Syracuse, the Fifteenth Ward. There he frequented a dive called the 800 Club, where black musicians and singers performed and jammed together. Lou and his band were accepted there and would occasionally work with some of the singers from a group called the Three Screaming Niggers. “The Three Screaming Niggers were a group of black guys that floated around the upstate campuses,” said Mishkin. “And we would pretend we were them when we got these three black guys to sing. So we would go down there once in a while and play. The people down there always had the attitude, the white man can’t play the blues, and we’d be down playing the blues. Then they’d be nice to us.” The Eldorados also sometimes played with a number of black female backing vocalists.

However, at first what made LA and the Eldorados stick out more than anything else was their car. Mishkin had a 1959 Chrysler New Yorker with gigantic fins, red guitars with flames shooting out of them painted on the side of the car, and “LA and the Eldorados” on the trunk. Simultaneously they all bought vests with gold lamé piping, jeans, boots, and matching shirts. Togged out in lounge-lizard punk and with Mishkin’s gilded chariot to transport them to their shows, the band was a sight when it hit the road. They had the kind of adventures that bond musicians.

Mishkin remembered, “One time we played Colgate and we were driving back in Allen’s Cadillac in the middle of a snowstorm, which eventually stopped us dead. So we’re sitting in the car smoking pot around 1 a.m., and we realized that we can’t do that all night because we’d die. The snow was deep, so we got out of the car and schlepped to this tiny town maybe half a mile away. We needed a place to stay so we went to the local hotel, which was, of course, full. But they had a bar there. Schupak was in the bar telling these stories about how he was in the army in the war, and Lewis and I are hysterical, we are dying it was so funny. Then the bartender said, ‘You can’t stay here, I have to close the bar.’ We ended up going to the courthouse and sleeping in jail.”

The Eldorados further distinguished themselves by mixing some of Lou’s original material into their set of standard Chuck Berry covers. One of Lou’s songs they played a lot was a love song he wrote for Shelley, an early draft of “Coney Island Baby.” “We did a thing called ‘Fuck Around Blues,’” Mishkin recalled. “It was an insult song. It sometimes went over well and it sometimes got us thrown out of fraternity parties.”

LA and the Eldorados played a big part in Lou’s life, providing him with many basic rock experiences, but he kept the band separate from the rest of his life at Syracuse. At first Lou wanted to make a point of being a writer more than a rock-and-roller. In those days, before the Beatles arrived, the term rock-and-roller was something of a put-down associated more with Paul Anka and Pat Boone than the Rolling Stones. Lou preferred to be associated with writers like Jack Kerouac. This dichotomy was spelled out in his limited wardrobe. Like the classic beatnik, Lou usually wore black jeans and T-shirts or turtlenecks, but he also kept a tweed jacket with elbow patches in his closet in case he wanted to come on like John Updike. However, in either role—as rocker or writer—Lou appeared somewhat uncomfortable. Therefore, in each role he used confrontation as a means both to achieve an effect and dramatize an inner turmoil that was quite real. For Hyman and others, this sometimes made working with Lou exceedingly difficult.

According to Allen, “One of the biggest problems we had was that if Lou woke up on the day of the job and he decided he didn’t want to be there, he wouldn’t come. We’d be all set up and looking for him. I remember one fraternity party, it was an afternoon job, we were all set up and ready to go and he just wasn’t there. I ran down to his room and walked through about four hundred pounds of his favorite pistachio nuts, and then I found him in bed under about six hundred pounds of pistachio nuts—in the middle of the afternoon. I looked at him and said, ‘What are you doing? We have a job!’ And he said, ‘Fuck you, get out of here. I don’t want to work today.’ I said, ‘You can’t do this, we’re getting paid!’ Mishkin and I physically dragged him up to the show. Ultimately he did play, but he was very pissed off.”

Reed seemed to at once want the spotlight and to hate it.

“Lou’s uniqueness and stubbornness made him really different than anyone I had ever known,” added Mishkin. “He was a terrible guy to work with. He was impossible. He was always late, he would always find fault with everything that the people who had hired us expected of us. And we were always dragging him here and dragging him there. Sometimes we were called Pasha and the Prophets because Lou was such a son of a bitch at so many gigs he’d upset everyone so much we couldn’t get a gig in those places again. He was as ornery as you can get. People wouldn’t let us back because he was so absolutely rude to people and just so mean and unappreciative of the fact that these people were paying us to get up and play music for them. He couldn’t have cared less. So we used the name Pasha and the Prophets in order to play there again. And then the people who hired us were so drunk they wouldn’t remember. He would never dress or act in a way so that people would accept him. He would often act in a confrontational manner. He wanted to be different.

“But Lou was ambitious. He wanted to be—and said this to me in no uncertain terms—a rock-and-roll star and a writer.”

***

In May 1962, sick of the stodgy university literary publication and keen to make their mark, Lewis and Lincoln, along with Stoecker, Gaines, Tucker, et al., put out two issues of a literary magazine called the Lonely Woman Quarterly. The title was based on Lou’s favorite Ornette Coleman composition, “Lonely Woman.”

Originating out of the Savoy with the encouragement of Gus Joseph, the first issue contained an untitled story, mentioned in the previous chapter, signed Luis Reed. It described Sidney Reed as a wife-beater, and Toby as a child molester. Shelley, who was involved in the publication, was convinced that just as Lou’s homosexual affair was mostly an attempt to associate with the offbeat gay world, the story was a conspicuous attempt to build his image as an evil, mysterious person. He was smart enough, she thought, to see that this was going to make readers uncomfortable. “And that’s what Lou always wanted to do,” she said, “make people uncomfortable.”

The premier issue of LWQ brought “Luis” his first press mention. In reviewing the magazine, the university’s newspaper, the Daily Orange, had interviewed Lincoln, who boasted that the magazine’s one hundred copies had sold out in three days. Indeed, the first issue was well received, but when everyone else on its staff apparently got lazy, Lou put out issue number two, which featured his second explosive piece, printed on page one. Called “Profile: Michael Kogan—Syracuse’s Miss Blanding,” it was the most attention-grabbing project Lou ever pulled off at Syracuse: a deftly executed, harsh attack upon the student who was head of the Young Democrats Party at the University. Allen Hyman recalled, “It said something like he [Kogan] should parade around campus with an American flag up his ass, which at the time was a fairly outrageous statement.” Unfortunately, Kogan’s father turned out to be a powerful corporation lawyer. “He decided that the piece was libelous,” remembered Sterling, “and he’d bust Lou’s ass. So they hauled him before the dean. But … the dean started shifting to Lou’s side. Afterwards, the dean told Lou to finish up his work and get his ass out of there, and nothing would happen to him.” By May of 1962, Reed’s literary career was off to a running start.

Despite this, Lou’s relationship with Shelley—not his classes—had dominated his sophomore year. They had spent as many of their waking hours together as was possible, camping out over the weekends in friends’ apartments, using fraternity rooms, cars, and sometimes even bushes to make love. Lou received a D in Introduction to Math and an F in English History. Then he got in trouble with the authorities again when a friend was busted for smoking pot and ratted on a number of people, including Lewis and Ritchie Mishkin.

“We smoked all the time,” admitted Mishkin. “But we didn’t smoke and work. We may have played and then smoked after and then jammed. Anyway, the dean of men called Lou, me, and some other people into his office and said, ‘We know you were smoking pot, so give us the whole story.’ We were terrified, at least I was. But nothing happened. Lou was angry. With the authorities and with the informer. But they were pretty soft on us. We were lucky, but then all they had to go on was the ‘he said, she said’ kind of evidence, so there was a limit to what they could do. But they had us in the office and they did the old, ‘We know because so-and-so said …’”

As a result of these numerous transgressions, and with his apparent academic torpor at the end of his sophomore year, Reed was put on academic probation.

***

The summer of 1962 was somewhat difficult for Lou. This was the first time he had been separated from Shelley for more than a day, and he took it hard. First, in an attempt to exert his control over her across the thousand miles that separated them, he embarked on a zealous letter-writing campaign, sending her long, storylike letters every day. They would begin with an account of his daily routine—he would go to the local gay bar, the Hayloft, every night—and tweak Shelley with suggestive comments. Then, in the middle of a paragraph the epistle would abruptly shift from reality to fiction and Lou would take off on one of his short stories, usually mirroring his passion and longing for Shelley. An exemplary story sent across the country that summer was “The Gift,” which appeared on the Velvet Underground’s second album, White Light/White Heat, and perfectly summed up Lou’s image of himself as a lonely Long Island nerd pining for his promiscuous girlfriend. “The Gift” climaxed with the lovelorn author desperately mailing himself to his lover in a womblike cardboard box. The final image, in the classic style of Yiddish humor that informed so much of Reed’s work, had the boyfriend being accidentally killed by his girlfriend as she opened the box with a large sheet-metal cutter.

Shelley, a classic passive-aggressive character, rarely responded in kind, but she did talk to Lou on the phone several times that summer, and he did not like what he heard at all. Lou had expected Shelley to remain locked in her room thinking of nothing but him. But Shelley wasn’t that kind of girl. Despite having commenced the vacation with a visit to the hospital to have her tonsils out, by July she was platonically dating more than one guy and at least one was madly in love with her. Despite the fact that Shelley was really loyal to Lou, the emotions Lou addressed in “The Gift” were his. He paced up and down his room in frustration. He couldn’t stand not having Shelley under this thumb. It was driving him insane.

Then he hit on a plan. Why not go out and visit her? After all, he was her boyfriend, he was writing to her every day or so and had called her several times. It sounded like the right thing to do. His parents, who had kept a wary eye on their wayward son that summer, still frowning on his naughty visits to the Hayloft and daily excursions on the guitar, were only too happy to support a venture that they felt was taking him in the right direction. At the beginning of August he flew out to Chicago.

Shelley had been adamantly against the planned visit, warning Lou on the phone that her parents wouldn’t like him, that it was a big mistake and wouldn’t work out at all. But Lou, who wanted, she recalled, “to be in front of my face,” insisted.

By now Lou had developed a pattern of reaction to any new environment he entered. His plan was to split up any group, polarizing them around him. In a family situation, as soon as he walked into anybody’s house, he took the position that the father was a tyrannical ogre whom the mother had to be saved from. On his first night in the Albins’ home, he cleverly drew Mr. Albin into a political discussion and then, marking him for the bullheaded liberal Democrat that he was, expertly lanced him with a detailed defense of the notorious conservative columnist William Buckley. While Shelley sat back and watched, half-horrified, half-mesmerized, Mr. Albin became increasingly apoplectic. Lou was obviously not the right man for his daughter. In fact, he didn’t even want him in the house.

The Albins had rented a room for Lou in nearby Evanston, at Northwestern University. Using every trick in his book, Lou pulled a double whammy on Mr. Albin, driving his car into a ditch later the same night when bringing Shelley back from the movies at 1 a.m., forcing her father to get up, get dressed, come out, and help haul out the mauled automobile.

Things went downhill from there. Lou made a valiant attempt to win over Mrs. Albin. Having dinner with her and Shelley one night when the man of the house was absent, Lou launched into his classic rap, saying, “Gee, you’re clearly very nice. If it wasn’t for the ogre living in the house …” But Mrs. Albin was having none of his boyish charm. She had surreptitiously read Lou’s letters to Shelley that summer and formed a very definite opinion about Lou Reed: she hated him with a passion—and still does more than thirty years later. In her opinion, Lou was ruining her daughter’s life.

As an upshot of Lou’s visit, Shelley’s parents informed her that if she continued to see Lou in any way at all, she would never be allowed to return to Syracuse. Naturally, swearing that she would never set eyes upon the rebel again, Shelley now embarked upon a secret relationship with Lou that trapped her exactly where Reed wanted. Since Shelley had no one outside of Lou’s circle in whom she could confide about her relationship with him, she was essentially under his control. From here on Lou would always attempt to program his women. His first move would always be to amputate them from their former lives so that they accepted that the rules were Lou’s.

Chapter Three

Shelley, If You Just Come Back

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: 1962–64

The image of the artist who follows a brilliant leap to success with a fall into misery and squalor, is deeply credited, even cherished in our culture.

Irving Howe, from his foreword to In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories by Delmore Schwartz

When Lou returned to Syracuse for his junior year, he rented a room in a large apartment inhabited by a number of like-minded musicians and English majors on Adams Street. The room was so small that it could barely contain the bed, but that was okay with Lou because he lived in the bed. He had his typewriter, his guitar, and Shelley, who was now living in one of the cottage-style dorms opposite Crouse College, which were far less supervised than the big women’s dorm. She was consequently able to live with Lou pretty much full-time.

The semester began magically with Shelley’s arrival. Lou whipped out his guitar and a new instrument he had mastered over the summer, a harmonica, which he wore in a rack around his neck, and launched into a series of songs he had written for Shelley over the vacation, including the beautiful “I Found a Reason.” Shelley, who was completely seduced by Lou’s music, was brought to tears by the beauty and sensitivity of his playing, the music and the lyrics. Lou played the harmonica with an intense, mournful air that perfectly complemented his songs, but was unfortunately so much like Bob Dylan’s that, so as not to be seen as a Dylan clone, he had to retire the instrument. It was a pity because Lou was a great, expressive harmonica player. In his new pad, he played his music as loud as he wanted and took drugs with impunity. It also became another stage on which to develop “Lou Reed.” He rehearsed with the band there, often played music all night, and maintained a creative working environment essential to his writing. He was really beginning to feel his power. His band was under his control. He had already written “The Gift,” “Coney Island Baby,” “Fuck Around Blues,” and later classics like “I’ll Be Your Mirror” were in the works.

By the mid-1960s, the American college campus was going through a remarkable transformation that would soon introduce it to the world as one of the brighter beacons of politics and art. One of the marks of a particularly hip school was its creative writing department. Few American writers were able to make a living out of writing books. Somewhere in the 1950s some nut put together the bogus notion that you could haul in some bigwig writer like Ernest Hemingway or Samuel Beckett and get him to teach a bunch of some ten to fifteen young people how to write. However, it had succeeded in dragging a series of glamorous superstars like T. S. Eliot (a rival with Einstein and Churchill as the top draw in the 1950s) to Harvard for six weeks to give a series of lectures about how he wrote, leading hundreds of students to write poor imitations of The Waste Land. The concept of the creative writing program looked good on paper, but it was, in reality, a giant shuck, and the (mostly) poets who were on the lucrative gravy train in the early sixties were, for the most part, a bunch of wasted men who had helped popularize the craft during its glorious moment 1920–50, when poets like W. H. Auden had the cachet rock stars would acquire in the second half of the century.

Delmore Schwartz was one of the most charismatic, stunning-looking poets on the circuit. He had been foisted on the Syracuse University creative writing program by two heavyweights in the field—the great poet Robert Lowell and the novelist Saul Bellow, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize—who had known him in his prime as America’s answer to T. S. Eliot. Unfortunately for both him and his students, Schwartz had by then, like so many of his calling, expelled his muse with near-lethal daily doses of amphetamine pills washed down by copious amounts of hard alcohol. Despite having as recently as 1959 won the prestigious Bollingen Prize for his selected poems, Summer Knowledge, when he arrived on campus in September 1962, Schwartz was, in fact, suffering through the saddest and most painful period of his life.

Sporting on his forty-nine-year-old face a greenish yellow tinge, which gave the impression he was suffering from a permanent case of jaundice, and a pair of mad eyes that boiled out from under his big, bloated brow with unrestrained paranoia, on a good day this brilliant man could still hold a class spellbound with the intelligence, sensitivity, and conviction of his hypnotic voice once it had seized upon its religion—literature. Schwartz once received a ten-minute standing ovation at Syracuse after giving his class a moving reading of The Waste Land. Unfortunately, by 1962 his stock was so low that none of the performances he gave at Syracuse—in the street, in the classroom, in bars, in his apartment, at faculty meetings, anywhere his voice could find receivers—was recorded.

Until the arrival of Delmore Schwartz, Lou Reed had not been overly impressed by his instructors at Syracuse. However, Lou only had to encounter Delmore once to realize that he had finally found a man impressively more disturbed than himself, from whom he might be able to get some perspective on all the demons that were boiling in his brain.

If Lou had been looking for a father figure ever since rejecting his old man as a silent, suffering Milquetoast, he had now found a perfect one in Delmore Schwartz. In both Bellow’s novel about Schwartz, Humboldt’s Gift, and James Atlas’s outstanding biography, Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet, many descriptions of Schwartz’s salient characteristics could just as well apply to what Lou Reed was fast becoming.

As Lou already did, Delmore entangled his friends in relationships with unnatural ardor until he was finally unbearable to everyone. Like Lou, Delmore ultimately caused those around him more suffering than pleasure. Like Lou, Delmore possessed a stunning arrogance along with a nature that was as solicitous as it was dictatorial. Both possessed astonishing displays of self-hatred mixed with self-love and finally concluded in concurrence with many of their friends that they were evil beings. Both were wonderful, hectic, nonstop inspirational improvisators and monologuists as well as expert flatterers. Grand, erratic, handsome men, they both gained much of their insights during long nights of insomnia.