Полная версия

Orchestrating Europe (Text Only)

But what is it? Almost any habitual, voluntary practice could be described as informal. It is not restricted to individuals who know each other – though nationality or language affinity, cultural rapport and shared professional ethos are important. Whatever it is must constitute the basis for continuous relations between the players, whether governments, officials or commercial organizations. It must include everything which does not appear in legal texts, all rules and conventions which may be policed but are not justiciable.

Informal politics are defined not so much by players’ status – any who wish and can establish credentials to the satisfaction of others can enter – as by the mode chosen to establish relationships. All players can choose between formal and informal modes and the shades of grey between them. There is no dividing line – only a spectrum. Rules and conventions are policed on both sides, with many nuanced penalties for infringement.

Inclusion depends on a player’s willingness to accept the rules and conventions of its own club or association. To a minimum extent, all players, like member states themselves, must demonstrate an element of altruism (European-mindedness) as well as basic self-interest, not only to be proper members of higher sectoral and European-wide groupings, but to make themselves acceptable to EU institutions and officials.

Informal politics exist wherever there are ‘grey areas’. As these are filled in and categorized over time, the informal may mutate, becoming, like the European Council, quasi-formal or ultimately fully formalized. But periodically new grey areas will open up as contexts or procedures change. Where interpretation is open to dispute, where there are margins of manoeuvre, where boundaries are imprecisely defined, where authorities have to exercise discretion, the informal will always flourish.

It exists most in conditions of plural bargaining where interdependence requires players to consort together to make agreements or risk losing the consensual base on which their status and the possibility of future agreements rests. It increases with the number of players, because none wishes to be isolated in the political marketplace; and it operates more easily and frequently in the Community than in nation states – whose modem forms of trilateral brokerage developed earlier in the twentieth century and have since grown older and more rigid; whose governments are also less open or willing to admit that it exists.

Its appearance is infinitely variable, but each aspect has certain common characteristics: impermanence, flexibility, subtlety. Inside groups and institutions it is disseminated as individuals are inducted, socialized and promoted, taking root most readily where there is professional training or practical experience. Political constructions damage it, for it is ultimately consensual, unlike the politics of politicians which tends to divide.

It evolves mechanisms for revision more easily than the formal system, and is closely compatible with the long Community tradition of setting markers in legal texts, to be implemented in riper circumstances at a later date. In that sense, it assumes both good faith and the continuity of ethos and convention among players, though not of course always in the same forms.

In what follows, I argue that this constitutes a distinct field with systemic characteristics, not merely a shadow or extension of the formal. But it is not a Manichean distinction: only at the ends of the spectrum are matters black and white. Unless the whole range is taken into account, analysis remains imperfect, since for want of it the strong probability is that the formal system will be less acceptable, flexible or efficient.

The formal and informal sides’ interactions are present in any known political system, since the only difference between them in a tyranny and a democracy is one of proportion: they exist in both. But in open systems the informal is far more pervasive, legitimate and well-grounded, even at the point of policy initiative. Looked at in this way, not only governments but the components of the modem state – ministries, civil servants, central banks, and the state as a whole – are players. Power is exercised through shifting alliances, depending on what is at stake in the polygonal activities which surround economic activity and the social life of individuals.

But its Community aspect is not the same as that in nation states, being more open, welcome, and effective to the point at which the formal might well silt up without informal mechanisms. As one very senior Brussels official put it, ‘if you were to stick to the formal procedures, it would take ten years every time … the more there is disagreement, the more the informal is necessary.’4 This argues that the EU’s slowly evolving statehood – which is a subtext throughout this book – will continue to differ in kind from the statehood of its members. Each player operates in a multinational range. Each of them has its own distinct global interests, its own concept of what is good for it within the European framework. It is this which it wants inserted, like a pacemaker, in the heart of Europe. No nation state has to contend with such a game, none is so much an artefact of the game.

What the EU will become is not something this book attempts to guess. Given the model of perpetual flux which the formula competitive symposium implies, that would depend on answering an impossible set of questions about the future of the nation state, which is at present still the EU’s main determinant. Yet that outcome will be affected by all the players, not just member states and Community institutions, in the double game in Brussels and national territories. How power is exercised in the Community is inseparable from the sum of all their transactions, a state of affairs which national governments would not permit at home but are powerless, because of their diversity, to prevent here.

By participating, players affect each other’s perceptions of one another and what each is doing. As a result, the European Union may be becoming more like a global market in political and economic terms, but not necessarily so in social or cultural respects since there is a wider assimilation at work, beyond the one that makes their behaviour patterns similar. As their perceptions change – faster with the onset of an internal market – so may their interests. Imperceptibly, the economic players may become European, whatever nation states do, whether or not a European public comes into existence to fulfil what, in national terms, remain ‘unnatural communities’. Yet the Community cannot be confined to the economic sphere because there are not even Chinese walls to separate economics from the political economy. If that makes the Community into a state, albeit of a different order from nation states, then the members of it must accept the outcome of what they have helped to create.

Sources

A book like this can only be written on the basis of elite oral history. Only one major archive, that of the Confederation of British Industry, was made available to us, from 1973 more or less to the present day. In amassing our own archive of over four hundred and forty interviews, we were able to hear the views of as complete a range of practitioners as seemed possible: Commission officials, Commissioners, member state administrators, politicians and Permanent Representatives, MEPs, judges and Advocates General, regional notables, representatives of peak institutions in the industrial, financial and labour sectors, and a considerable variety of firms’ and financial institutions’ executives.

We should emphasize that this selection was not Brussels-oriented, but incorporated a variety of standpoints: those of twelve member states, weighted according to size, four applicants for membership, five regions in the five largest member states, and a range of firms and sectoral organizations chosen to illustrate particular cases and their diversity of ethos and orientation. The choice of retired respondents as well as those in post enabled us to cover the period 1973 to 1994, and in particular to obtain insights into less-studied areas such as the Court of Justice, and the Committee of Central Bank Governors in Basel.

There were, inevitably, some arbitrary aspects to the selection, since not all those asked were willing or available to be interviewed. We concentrated more, for example, on the European Court of Justice than the European Parliament, whose powers and informal structures are still in the process of evolution; and on certain Commission Directorates, dealing with industries and the financial sector, rather than others. The interviews themselves naturally vary in quality, but at best constitute a significant weight of evidence. Copies have been lodged at the Sussex University European Institute, at the European University Institute in Florence, and at the Hoover Institution, Stanford, California.

These are in the form of notes, not verbatim transcripts, being the researcher’s record of what took place. This creates problems of attribution. Some of the material would not have been given if the sources were to be made plain so soon after the event; in other cases, where many of the respondents agreed, footnotes would have been unmanageably long. Where a choice is made between different interpretations, attribution would have been invidious and unfair to those who spoke in good faith. Furthermore, no individual could be taken as representative of any firm or institution, let alone a whole sector of government. Hence they are referred to here, where direct quotation occurs from the notes, but only by indexed numbers; in the archives they are referred to by a general title such as ‘DG3 Official’ or ‘Executive of such-and-such a company’.

The problems connected with oral history are well known. They include lapses of memory, vindictiveness, falsification, excessive discretion, trivia, over-simplification, lack of perspective and various sorts of distortion and hindsight.5 The interviewer in turn has his or her limitations, ranging from choosing an unrepresentative sample to undue deference or bias in questions; not forgetting that the method is often so enticing that it may unwisely be preferred to official or other printed sources.

A distinction should of course be made between oral history, used predominantly to record memoirs of the less articulate (whose lifestyles rarely appear in documentary form), to construct alternative or ‘peoples’ histories’, and elite oral history, whose respondents are used to presenting themselves and their views fluently. Only the latter have been used here because they offer an unrivalled insight into motivations, interpretations, factors in policy-making, and the personal or group interchanges between those who belong to one or other of a number of elites.

The advantages clearly outweigh the risks, which prudence and practice can to a large extent mitigate, though never eliminate. Elite oral history, constructed from discussion with participants in the midst of the action, provides assessments of personalities and events which may not be recorded in documents even when these eventually become available for research. More important, it gives guidance on organizational relations which may well substantially modify observations found elsewhere. No organigram can be weighted sufficiently to show the informal channels or the difference between real and ritual communications.

Some institutions have only a limited effective life before becoming bureaucratized. Some are so informal as to leave no documentary record. All networks operate differently, depending on the question at issue and the level at which they relate to others. Vast as the flood of EC documentation is, ranging from formal reports to discussion documents, these alone cannot establish what on any given question is the place each player in each game merits. Interviewing gives insights into the assumptions or ethos of a group and its collective aims which, in the case of commercial organizations, may never otherwise be fully documented.

Presidents and principal Commissioners relevant to the main themes since 1981

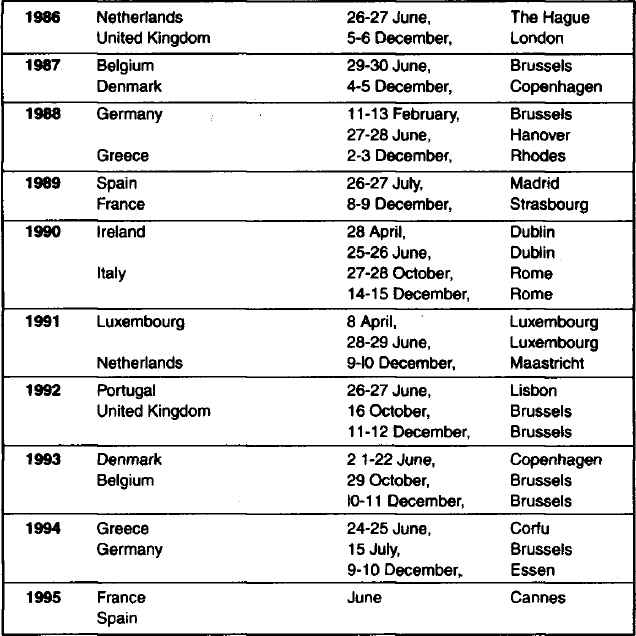

President (81-84)External relationsEcon. and financeGaston ThornWilhelm Haferkamp (Lorenzo Natali)Francois-Xavier Ortoli IndustryCompetitionTransportEtienne DavignonFrans AndriessenGeorgis Contogeorgis Science/ResearchTelecomsInternal market/Financial institutionsEtienne DavignonKarl-Heinz Narjes (int. market) Christopher Tugendhat (financial institutions) Regional policyDG XXIII (enterprise policy, tourism,…)Antonio GiolittiAntonio Giolitti President (85-88)External relationsEcon. and financeJacques DelorsWilly De Clercq (Claude Cheysson)Alois Pfeiffer IndustryCompetitionTransportKarl-Heinz NarjesPeter SutherlandStanley Clinton Davis Science/ResearchTelecomsInternal market/Financial institutionsKarl-Heinz NarjesArthur Cockfield Regional policyDG XXIII (enterprise policy, tourism,…)Alois PfeifferCarlo Ripa di Meana (Abel Matutes) President (89–92)External relationsEcon. and financeJacques DelorsFrans Andriessen (Abel Matutes)Henning Christophersen IndustryCompetitionTransportMartin BangemannLeon BrittanKarel van Miert Science/ResearchTelecomsInternal market/Financial institutionsFilippo Maria PandolfiFilippo Maria PandolfiMartin Bangemann (Leon Brittan) Regional policyDG XXIII (enterprise policy, tourism,…)Bruce MillanAntonio Cardoso e Cunha President (93-94)External relationsEcon. and financeJacques DelorsLeon Brittan Hans van den Broek (Manuel Marin)Henning Christophersen IndustryCompetitionTransportMartin BangemannKarel van MiertAbel Matutes Science/ResearchTelecomsInternal market/Financial institutionsAntonio RubertiMartin BangemannRaniero Vanni d’Archirafi Regional policyDG XXIII (enterprise policy, tourism,…)Bruce MillanRaniero Vanni d’Archirafi President (95-99)External relationsEcon. and financeJacques SanterHans van den Broek Leon Brittan (Manuel Marin) (Joao de Deus Pinheiro)Yves-Thibault de Silguy IndustryCompetitionTransportMartin BangemannKarel van MiertNeil Kinnock Science/ResearchTelecomsInternal market/Financial institutionsEdith CressonMartin BangemannMario Monti Regional policyDG XXIII (enterprise policy, tourism,…)Monika Wulf-MathiesChristos PapoutsisPresidencies of the Council of Ministers and Meetings of the European Council since 1970

The European Integration Experience

RICHARD T. GRIFFITHS

1

1945–58 1

In 1945 western Europe counted the cost of yet another continental conflict, the third in the space of seventy years involving France and Germany. Yet by 1958, these two countries had formed the core of a new supranational ‘community’, transforming intra-state relations in the space of thirteen years. It represented a development to which many in 1945 would have aspired but which few would have dared to hope would be realised so quickly. This evolution marked the beginning of what is commonly referred to as ‘the process of European integration’.

It is worth pausing to consider the double connotation of the word ‘integration’, since the expression is used to imply both a sequence of institutional changes (all involving the surrender of national sovereignty) and the enmeshing of economies and societies that it is intended should flow from these measures. To be more precise, ‘integration’ was one of the goals of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), founded by France, Germany, Italy and the Benelux countries in 1952, and of the European Economic Community (EEC) and EURATOM, both founded by the same six states in 1958. Nonetheless, we should realize that this term intentionally excepts many other types of institutional change on the grounds that they are ‘inter-governmental’, and do not involve the surrender of sovereignty. It also marginalizes other sources, institutional or otherwise, of Europe’s growing ‘interdependence’.

The ‘process of integration’ is given pride of place in the memoirs of those most closely identified with it. This is because they were convinced of the historical importance of their achievements, but also because they were eager to win the propaganda war against the existing inter-governmental alternatives, which they perceived as weak and incapable of sustaining further development.2 The institutions and workings of the new supranational communities were pushed further into the limelight by the writings of a generation of political scientists, attracted by the novelty of provisions in the Community and the dynamic inherent in their operations. Their attitudes have subsequently been projected backwards onto the past in a series of histories which concentrate on the struggle for supranational, even federal, institutions, but which mostly exclude developments elsewhere. Yet the EEC came onto the scene relatively late in the day and although the ECSC had been created six years earlier, it was limited in its economic impact. Insofar as the economic boom of the 1950s and the trade expansion that accompanied it had been caused by institutional changes, its origins lay elsewhere. The EEC’s creation witnessed the end of western Europe’s financial and commercial rehabilitation and not the beginning.

Since the late 1970s, a new generation of historians, trudging in the wake of the so-called ‘thirty year rule’ – the period before which some national governments grant access to their archives – have been rewriting the history of this period. Much of this work has still to be assimilated into mainstream accounts but, once it has been, its main achievement will have been to widen the perspective and context of analysis and to rediscover the complexity of the past. This, in itself, has often constituted an antidote to the simplistic ‘high politics’ analysis (and sometimes straight federalist propaganda) of existing accounts. However, thus far historians have been less than successful in agreeing on a coherent ‘alternative’ explanation to federalist accounts.

One casualty of the new history has been ‘American hegemony theory’, at least in its early chronology. The ‘hegemonic leadership’ theory argues that the existence of an American political hegemony allowed for the reconciliation of lesser, more localized national differences. Thus, at the height of its relative economic, political, military and moral power, the United States is supposed to have used its good offices to establish a liberal world order and, more particularly, to have supported ‘integrative’ solutions to world problems that mirrored its own history and that seemed to underpin its own success and prosperity. The new, revisionist literature has demonstrated the limits of hegemonic power and has raised awareness of the degree to which Europe has been able to resist American influence. Equally, it has underscored the ‘European’ as opposed to the American motives in seeking to ‘change the rules’ of European inter-state relations through institutional innovation and reform.

Secondly, historians have stumbled into the ‘actor-agency’ dilemma already familiar to political scientists. Initially, much of the literature focused on the actors: the ideas that drove them, the positions of political power they occupied and their role in the nexus of key players, together with the political processes which they adapted or invented to accomplish their ends. The need to find peace in western Europe and to build a bulwark against totalitarianism formed the ‘real world’ components in this analysis. Subsequently, historians working usually in governmental archives have found a more prosaic subtext to these events. Far from an heroic, visionary quest for a better future, they recount the story of an entrenched defence of perceived national interest. This version of history is often juxtaposed against the earlier approaches but the two are not necessarily irreconcilable. The international agreements that underpin the integration ‘process’ were usually submitted to parliamentary scrutiny and the threat of rejection placed constraints on too cavalier a surrender of sovereignty on issues of real public concern. Moreover, the whole idea of ‘supranationality’ is to adapt the rules of future political behaviour, to determine a new ‘how’ for the political process. It may remain a primary goal even if it requires a surrender of consistency or elegance in the short-term.

This version of ‘perceived national interest’ is itself the outcome of domestic political processes and is susceptible to changes in the balance both within governments and between governments. It is some way removed from the concept of national interest as formulated by ‘realist’ or ‘neo-realist’ scholars, who argue that the state is a unitary actor, intent on maximizing its interests, whose foreign policy behaviour can be understood from an objective reading of its relative geo-political position. Within the literature of integration this type of analysis made its appearance in the early 1960s3 and has recently been revived. In its current version, the viability or survival of post-War, democratic states lay in their ability to satisfy a ‘consensus’ built around comprehensive welfare provision, economic growth and agricultural protection. According to this critique, only when these goals can not be met in any other way do governments agree to surrender sovereignty, usually emerging stronger as a result.4 Aside from postulating an implausible degree of coherence in collective decision-making, this version of events both exaggerates the dangers confronting European states in what was, after all, the middle of the greatest economic boom in modem history, and the importance of supranational mechanisms in resolving residual commercial challenges.

Despite the awesome destructive power of the weaponry deployed during the Second World War, Europe’s post-War productive capacity was not as damaged as has often been claimed. Although the image of utter devastation still persists, the material damage was concentrated on areas of infrastructural investment (mainly transport and housing) and much less on productive capital. Most historians now accept that Europe’s industrial capacity was larger in the late 1940s than it had been in 1938 and, in some respects, better adapted to the needs of the post-War era. Without taking this into account, it is impossible to understand Europe’s rapid industrial recovery. Already by 1947, most western European countries had surpassed their pre-War levels of industrial output. Germany, the main exception, was not to do so until 1950, by which time western Europe as a whole was producing almost 25 per cent more than in the pre-War years. Although the expansion of manufacturing was remarkable, serious problems still remained. Basic industries, such as coal and steel, struggled to recapture pre-War levels and the neglect and destruction of transportation systems also caused major bottle-necks. Agricultural production was not as severely weakened within western Europe, but recovery was much slower than it had been for industry. Although a poor harvest in 1947 reinforced the negative image of the condition of European agriculture after the War, this was a serious but isolated incident and output rebounded quickly. Even so, it was not until 1950 that production recovered to its pre-War levels.5

The impact of all these changes was to widen the productivity gap between Europe and the USA. In industry alone, the USA had emerged from the War with double the output of 1938 and, despite the dislocation of adjusting to peacetime conditions (and a short-lived recession), had added further to this position by 1950. Without closing the gap, it was felt that Europe would be unable to repair the trade imbalance with the US and would be unable to sustain acceptable standards of welfare for its peoples. This problem was aggravated by the impact of the War on Europe’s trading relationships, both with each other and with the rest of the world.