Полная версия

North Side of the Tree

North Side of the Tree

MAGGIE PRINCE

Dedication

For Chris, always

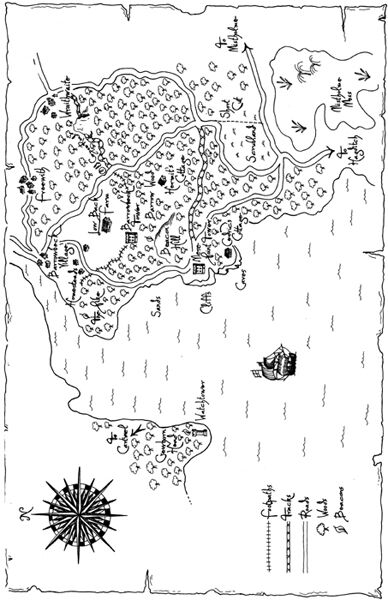

Map

Epigraph

In transposing Beatrice’s story into modern English,the tone and content of her original narrativehave been preserved throughout,and her exact words wherever possible.

It is the late 1500s. Queen Elizabeth I is on the throne of England…

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Keep Reading

Glossary

Acknowledgements

Praise For Raider’s Tide

Also by Maggie Prince

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

I walk the Old Corpse Road again. In the dawn light the woods are full of birdsong and the waking voices of sheep. Around me, oak and hazel trees are turning to red and gold and ruin.

I am on my way to visit my sister who is living at Wraithwaite Parsonage in order to avoid being killed by my father. I move carefully amongst the trees, because this is the way he may be coming home, tired and edgy from a night’s robbery on The King’s Strete, some miles to the east of us.

I do not wish to meet my father, but I am not in a position to criticise him, because I too have a secret. I am a traitor. Three people know it, and their silence is all that stands between me and being burnt at the stake.

I reach the rockface that makes the Old Corpse Road such a quick but difficult short-cut to our neighbouring village, and climb the steps cut into it, breathing in the earthy smells of autumn. Stunted yews and clumps of heather grow out of clefts in the limestone, and I hold on to them to haul myself up. At the top I nearly collapse with fright. Two strange men are asleep amongst the roots of a beech tree, perilously close to the edge of the escarpment. They have swords and axes at their sides. I tiptoe past them. These must be some of the men who walked from all over the district to march on Scotland with my father. Last spring we were raided by Scots, as we often are in this part of the country. Our men were to have raided them back, but this has now been put off until next spring, since our enemies have been forewarned by a fugitive Scot who hid for months in a hermit’s cottage in the woods, and discovered our plans.

Oh Robert, where are you now? Are you safe? You may be gone from here, but I wish very much that you could be gone from my mind too.

As I set off through the thinning trees, on to the heathland which surrounds Wraithwaite, I glance back at the two men and silently wish them well. I’m glad this raid has been abandoned, and that they do not have to go to war. Maybe the raid on Scotland will be forgotten altogether now. With Robert gone, and all the preparations for winter needing to be made, anti-Scottish feeling along the border is dying down.

I pass the first cottages along the track to Wraithwaite. A woman is hanging out her washing. We call, “Good morrow, mistress,” to each other, and she glances at the sky and adds, “I’m tempting fate. It’s going to rain.”

A flurry of wind blows the fallen leaves into a spiral ahead of me, and I nod in agreement. “You’re right, mistress.”

Sometimes, relief just washes over me. Little exchanges like this feel such a luxury, after being on the wrong side of the law for so long. I can pretend to be a respectable member of the community again, working the family farm, preparing to become betrothed to Cousin Hugh. Robert is gone. He wasn’t caught, and neither was I. My narrow escape makes me want to be very, very good indeed, even to the extent of marrying Hugh, my childhood playmate, as is expected of me, no matter how ludicrous it might feel.

The parsonage stands on the far side of Wraithwaite Green. It is a beautiful stone house, but in poor repair. There is worm in its doorposts, and its roof slates are pushed out of kilter by tuffets of bright green moss. John Becker, our young and beautiful parson, was my teacher until I turned sixteen earlier this year. He knows my secret. He also saved me from drowning a month back. The warmth which once developed between us during long afternoons in a drowsy classroom has many a time teetered on the verge of becoming something more. I daren’t look too closely at my feelings for John Becker, if I am indeed to redeem myself by marrying Hugh.

I walk up to the front of the house. Over the door, carved into the lintel, are the words Truth and grace be to this place. I can hear someone chopping wood behind the house, so when no one answers my knock, I walk round to the back. John is chopping logs. He is shirtless and in coarse woven breeches and leather jerkin. He looks most unlike a priest. He hasn’t seen me. I pull my cloak tightly round me and watch him swinging the axe at log after log, splitting them with the grace of long practice. The back of his neck is running with sweat. His dark curls look chaotic and unkempt.

I say softly, “Hello John…” and he turns. He is not an easy person to catch unawares, but I do so then. He stares at me for a moment, then secures the axe with a gentle chop into a new log, and comes over to me. I start to say, “Verity sent word that she wants to see me…” but the words dry in my throat as John Becker holds me by the shoulders and kisses me full on the lips. I feel a shock of such proportions that for a moment I scarcely know where I am. I look up at him. Next to us in the stables his black horse, Universe, stamps and snorts.

John says, “I refuse to go on pretending. I know it’s probably too soon after your Scot, Beatie, but…”

There are footsteps behind me, and someone whistling. I turn. It is my sister, Verity.

“Beatie!” She comes out of the house and hugs me, then glances curiously from one to the other of us. “Well, I do declare,” she murmurs.

Universe is now trying to kick the stable door down. John unbars the top half of it. “I’d better let him out into the meadow. You two go in.” He smiles at Verity. “You have matters to discuss, I think. I’ll join you later.”

My sister has been here for many weeks now, after angering my father by her desire to marry not her Cousin Gerald, as the family decreed, but James Sorrell, a young neighbouring farmer. James also had to take refuge here from my father’s wrath for a while, but is now back tending his own farm, protected by two sturdy bodyguards, George and Martinus. They were once my father’s henchmen before they too angered him and were sent away. Many people anger my father. Most end up elsewhere.

I go into the kitchen to greet Mother Bain, John’s deaf, elderly housekeeper, then follow Verity up the narrow wooden stairs and along the landing to her room. The parsonage is in even worse fettle inside than out. The beams over our heads are crumbling to dust in places, and the door is so warped that it gapes against its frame when I shut it behind me. Verity’s bed, though, is beautiful: pale old oak carved with scrolls and animals, and hung about with fine grey velvet curtains. She climbs up against the heap of bolsters at the head of the bed, and I sit on the end. The feather mattress shifts comfortably to the shape of my legs. Verity is still in her nightsmock, a vast linen article of smothering decency. Her day clothes lie on a cedar chest by the wall. “Don’t you want to get dressed?” I ask her.

She twists a corner of the linen sheet round her finger, staring at it. “Nay, Beatie. I have to have some new clothes made. I can’t get into these any more. Will you send Germaine over to measure me? I have to tell you this, and I want you to tell Mother, but no one else. I’m with child.”

Verity, at fifteen, is a year younger than me. I gape at my younger sister and feel many things. I feel impressed. She has done what I have not. I feel jubilant. There is to be a new life in the family, and myself an aunt. Most of all, I feel terrified. What fearsome things Verity has ahead of her – my father’s rage, the whisperings of neighbours, the dangers of childbirth.

“Oh Verity.” For a moment I can think of nothing else to say. She is looking at me intently, looking for my reaction. I add stupidly, “James’s child.”

“Of course. You surely hardly imagined Gerald’s.”

“Are you happy? How do you feel?”

“Sick, but wonderful. Father has no choice now but to let me marry James.”

“Was that why you did it?”

“Heavens no. I did it because I wanted to. Truly Beatrice, you are not being the support I’d hoped.”

“I’m sorry. I’m truly glad for you. How long have you and James…?”

“All year. All spring and summer, until we came here and John would not allow it any more.” She leans back amongst the bolsters and closes her eyes. “James bought me some ginger root from the pedlar, for the sickness. Would you pass me a piece, please?”

I pass her a blue ginger jar from the top of the clothes press. “This must have cost him a fortune. He is truly your slave, I think.”

She looks at me sharply. “And I his.”

I hesitate. “Is it not a problem… that is, might it not at some time become a problem… that he is uneducated? That he cannot read nor write?”

I feel I am on dangerous ground, but Verity simply replies, “No.” After a moment she adds, “Anyway, John is going to teach him.”

I am suddenly flooded with optimism, and an unrealistic hope that my father will accept the situation. I ask, “Does John know you’re with child?”

“He does now. I told him yesterday. He says he’ll speak to Father for me.” She smiles. “So, Beatie, is our unfortunate father to have a double shock then, judging from what I saw earlier? Are you finally seeing the point of heavenly John?”

I feel a blush rising past my ears. “Verity, you saw nothing. I’m going to marry Hugh. That’s all there is to it.”

She smiles, and passes me the ginger jar, and I take a piece and half choke on its savage flavour.

By the time I am ready to set off again the rain has set in, a fine drizzle billowing across the green. “You really ought to get yourself another horse.” Verity stands with me on the front step. “I know how sad you are that poor Saint Hilda drowned, but you can’t keep on walking everywhere.”

“Plenty of other people do.”

She rolls her eyes. “Take Meadowsweet. Germaine can bring her back for me later.”

John comes up behind us. “I’ll take you home on Universe, Beatie.”

“I’d truly rather walk,” I reply, but he has already gone round the side of the house to catch his horse in the meadow. Verity reaches down my cloak from a peg, and Mother Bain comes out of the kitchen to say goodbye.

“Goodbye, Mistress Bain.” I bend to kiss her cheek.

“Goodbye. God bless you, lass. Take care of yourself. I feel there is some darkness hanging over you.” Mother Bain tends to make these apocalyptic remarks in such a practical tone of voice that they take a moment to sink in. She has a reputation as a seer, and has issued accurate warnings before.

“What is it, Mistress Bain?” I rub my arms to take the gooseflesh away.

She frowns. Her thin hand trembles on my wrist. Then she shakes her head. “Nay. Nought. I know not.” She passes her hand back and forth across her eyes, and returns to the kitchen.

Verity drapes my cloak round my shoulders. “You know, Beatie, I think there’s a lot you don’t tell me. You know all my secrets now. Tell me some of yours. We’ve lost touch since I left Barrowbeck.”

For a moment I consider it. It would be such a relief to talk about Robert, but there would be no point. It would be an extra burden on Verity, having to keep the terrible secret that her sister sheltered the enemy. Just now she is quite burdened enough, and likely to be more so. I shrug. “I have no secrets,” I lie. “Except that before, I did not wish to become betrothed to Hugh, and now I do. It is the sensible thing. It isn’t as if I loved anyone else – not in the way that you love James. We’ll keep the farm in the family, and I’ll see more of you again once you’re married to James and living just down the valley.” I kiss her cheek. “Now that Cousin Gerald cannot marry you, he can marry whomsoever he likes, and everything will work out just as it should.”

Verity gives me a cynical look. “How tidy, dear sister. Why do I feel that life is not like that? Anyway, what about…”

She falls meaningfully silent as John reappears at the front door, leading Universe saddled and ready. “Shall we go?” he asks. “Do you mind riding astride? The sidesaddle won’t fit us both.”

I hesitate, transfixed at the thought of riding all the way to Barrowbeck in such close proximity to John Becker. He adds, “We could go the long, easy way, or quickly by the Old Corpse Road.”

“Oh… quickly by the Old Corpse Road. I have to get back for the milking.”

I climb up, using the stone water trough as a mounting block before he can lift me, as he had seemed about to. I am becoming more accustomed to the wobbly experience of riding astride, these past weeks, after a lifetime of riding comfortably seated in my sidesaddle. A life of treason does bring some startling new experiences. John swings up behind me. His left hand grips the reins and his right hand grips my waist. He walks the horse forward and I wave to Verity, who pulls a mad, swooning face at me behind John’s back.

On the outskirts of Wraithwaite the woman I saw earlier is pulling her washing off the line and dumping it in a big wicker basket. I call to her, “You were right about the rain, mistress.”

She stares at us with her hands full of washing. “Aye, Mistress Garth. Indeed I was.” She gives John and me a slow, interested look, then glances skywards. “Mebbe you could put in a word for me up there to get it stopped, eh mistress, if you’ve got the influence?”

I laugh. John halts his horse and asks her, “Do you want to go and hang all that in the parsonage barn, Mistress Thorpe?”

She scrapes her sodden cap off her forehead and answers, “Aye parson, I’d appreciate it. I’ll send Alice over. I thank you.” Alice, her maidservant, a ten-year-old orphan from a neighbouring village, comes out of the house with another empty washing basket. I notice she has two black eyes.

John says, “Good morrow, Alice,” and regards her for a moment, then adds, “I’ll call in on my way back, Mistress Thorpe, and have a word with you.”

I can feel the two of them watching us go. I glance over my shoulder at John as Universe quickens into a trot. “You do realise it’s going to be all over the district by evening, John, that the parson has been out riding with Beatrice Garth at daybreak in the pouring rain.”

He laughs, and rests his chin on the top of my head. “Well then, I daresay we shall both be ruined.”

Chapter 2

There are more strangers about now, on the plateau and in the woods, armed men who would have marched on Scotland with my father, emerging from amongst the trees, where they have spent the night.

“They’ll all be at the tower later,” I tell John, “for a paying-off from Father before they go home.” We haven’t talked much during the journey. The full realisation of Verity’s news has been coming over me, and I am deeply apprehensive about my father’s reaction.

When we reach the rim of the rockface we both dismount. John says, “You go first. I’ll follow right behind with Universe. He dislikes this path. He’s a big baby about it. He may need a little coaxing.”

“Truly John, I can go on from here by myself. I don’t need you to come any further.”

He taps his whip against his thigh. “Not with all these moss-troopers about, heavens no. They may be harmless, but we don’t know them.”

I set off down the rough steps, holding up my skirts with one hand and supporting myself against the damp stone with the other. I turn to watch John pulling on the reins, and Universe’s big head stretching out reluctantly. John talks to his horse softly, asking in seductive tones why the animal is making such a fuss, and I feel like making a fuss myself, just to be spoken to in such a way. Universe’s round flanks graze the rock sides; he flicks his tail and snorts. Stones clatter down, hitting me. Finally, we all reach the bottom.

John pats his horse’s neck, and waits for the animal to calm down. He looks at me and says, “Well, Beatrice.” My heart jolts. I pull my hood further forward over my head, even though the rain is easing. John pushes his whip down his boot and scratches his leg. He asks, “Did you love him… your Scot?”

I shiver as a gust of wind is funnelled down through the rift in the rock. I don’t feel capable of talking about Robert out here in the woods, where his ghost shrieks at me from every tree.

“I cared about him,” I answer stiffly. “Care about him… But love? I think that is another matter. What are you asking me exactly? Whether Robert and I were lovers?”

“Robert? Ah, I never knew his name.”

“There’s no reason why you should have.”

“No, I wasn’t asking whether you were lovers. I couldn’t care less if you’d had every man in the valley.”

I give a snort of laughter, but he is being serious, and instantly I feel childish. I ask him, “How old are you, John?”

“Twenty-five.”

“I’m sixteen.”

“I know, but older than your years, I think. Look, we don’t have to talk about this now. I was going to wait for you to get over the Scot, but since you half-drowned, I’m so afraid of losing you…”

I interrupt him. “John, I shall always be grateful to you for saving me…”

“Don’t! I don’t want to hear that. I don’t want to trade on having fished you out of the ocean. There was something between us before that, wasn’t there?”

I look back at the rockface. Dazzling streaks of light are stabbing through the clouds above it. John looks too, and for a moment we are both immobilised by the beauty of it. “Yes,” I answer. “Yes, there was.”

John takes hold of my hand and kisses the palm. “So, can you just tell me it isn’t impossible?”

I touch his hair. It is wet from the rain, and still uncombed. I answer, “No, I can’t tell you that. It is impossible. Verity will be leaving Barrowbeck to farm with James at Low Back. Who will run the farm if I go too? I have to marry Hugh and stay.”

For what seems a long time we stare at one another. When we do speak, it is simultaneously, and reduced to politeness. “I should get back, John.”

“Have you started your lessons with Cedric yet?” He releases my hand and steadies the horse so that I can remount.

“Not yet. I’m still busy with the winter planting, and stocking the root cellar. There’s time enough.” Cedric, also known as the Cockleshell Man, is our local healer, a close friend of my mother, and soon to be my teacher in the arts of healing and herbalism.

John and I ride together in silence down through the woods, across a stream, up a steep bank where ferns and tree roots coil out of the earth. I wish we had not had this conversation. Before, I could imagine all sorts of unspoken impossibilities. Now I have been forced to face reality.

Where the trees thin out, Barrowbeck Tower comes into view in its clearing. I glance back at John. “Now I really do want to go on alone, John. It would be better if you were to see Father about Verity and James when the paying-off is over. Let him calm down a bit after handing out all that money. You must be careful of his temper. It’s getting more violent than ever.”

“I know.” John halts the horse and dismounts, and helps me down. He remains with his hands on my waist. Around us, the woods are quiet. Damp spiderwebs show up on the bushes. A flurry of rainwater splatters down on to our faces. He says, “I’ll come over this afternoon to speak to your father about Verity.”

“It won’t be easy.”

“I know. He doesn’t like me.”

“You’re always reprimanding him.”

“He deserves it.”

I kiss him on the cheek. “Goodbye John.”

“Goodbye Beatrice.” He kisses me on the mouth. Caught unawares, I put my arms round him and kiss him back.

A twig snaps nearby. We both jump. Universe is pricking his ears and glaring into the undergrowth. The bushes rustle and a voice says, “Good morrow, parson. Greetings, mistress.” It is Leo, our cowman.

I step back, speechless. John replies, “Good morrow, Leo. How pleasant to see you.” Leo is giving us an astounded look. I can see through his eyes my untidied hair and flushed face. I wonder how much he has seen. I try to imagine the repercussions if it reaches my father that his daughter has been seen kissing the parson.

“I must get back.” I pull my cloak round me.

John says calmly, as if we had merely been on a nature walk, “Go carefully, Beatrice. I’ll watch you as far as the tower,” but I hurry away, taking another path which leads me out of their line of vision.

“I’ll walk along with you if you’re heading back to the rockface, parson,” I can hear Leo saying behind me. “There’s a sight too many strangers in t’valley today for my liking. I’m just checking a few little snares I’ve set…” Their voices fade as I rush as far away from them as possible.

I am almost out into the lea now, thinking wildly about what I can say to Leo to ask for his silence. I dawdle at the edge of the trees, and decide to wait for him to come back this way from emptying his snares. The rain is heavier again now, and the wind is rising. Grey planks of rain come skimming over the Pike from the sea. I can see the watchman on the battlements of the tower pulling his hood up. I decide to shelter here and rehearse what I shall say. Leo will surely understand. Everyone employed at Barrowbeck Tower knows the necessity of avoiding my father’s temper. I clutch my own hood under my chin to keep the rain out, and this is how I do not see them coming.

“Ha!”

The voice, hands, body all come at once. A massive lout in dark, dirty clothing leaps from the bushes and knocks me to the ground. Another, shorter man follows him. I see a flash of brown jerkin and blue breeches. As I draw in my breath to scream, a stone is rammed into my mouth, crashing against my teeth. Grit and soil choke my voice. A knife flashes before my eyes.

“Back from seeing your fancy man, eh? Let’s have your money, lady.” The first man pinions my arms whilst the second grapples at my waist to see if I have a purse. I writhe and try to scream, but my throat is full of gravel, and all I can do is cough. I struggle to reach my knife, but the first man finds it before I can and rips it from my belt in triumph. “She’s no gold or silver, but I’ll have this pretty bit of ironmongery instead.” He hooks it into his own greasy green belt, then mutters, “Now what else can we tek off her, eh?”