Полная версия

Miss Dahl’s Voluptuous Delights

Miss Dahl’s Voluptuous Delights

Sophie Dahl

photographs by

Jan Baldwin

Dedication

For Jamie, at whose table I wish to grow old. With all my love.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Cook’s notes

Introduction

Autumn

Autumn breakfasts

Poached eggs on portobello mushrooms with goat’s cheese

Rice pudding cereal with pear purée

Omelette with caramelized red onion and Red Leicester

Tawny granola

Musician’s breakfast (home-made bread with Parma ham)

Indian sweet potato pancakes

Baked haddock ramekin

Autumn lunches

Spinach and watercress salad with goat’s cheese

French onion soup

Squid salad with chargrilled peppers and coriander/cilantro dressing

Baked eggs with Swiss chard

Chicken and halloumi kebabs with chanterelles

Spinach barley soup

Buckwheat risotto with wild mushrooms

Autumn suppers

Peasant soup

Sunday roast chicken and trimmings

Paris mash

Sea bass in tarragon and wild mushroom sauce

Lily’s stir fry with tofu

Aubergine/eggplant Parmigiana

Grilled salmon with baked onions

Winter

Winter breakfasts

Pear and ginger muffins

Scrambled tofu with cumin and shiitake mushrooms

Kedgeree with brown rice

Scrambled eggs with red chillies and vine tomatoes

Winter fruit compote

Porridge with apricots, manuka honey and crème fraîche

Hangover eggs

Grilled bananas with Greek yoghurt and agave

Winter lunches

Warm winter vegetable salad

Chicken soup with chickpeas

Spelt pancakes filled with cream cheese and butternut squash

Pasta puttanesca

Hollers’ curried parsnip soup

Chargrilled artichoke hearts with Parmesan and winter leaves

Chestnut and mushroom soup

Winter suppers

Brown rice risotto with pumpkin, mascarpone, sage and almonds

My dad’s chicken curry

Monkfish with saffron sauce

Fish pie with celeriac mash

Cauliflower cheese

Buttermilk chicken with smashed sweet potatoes

Christmas done as healthily as it can be

Spring

Spring breakfasts

Grilled papaya/pawpaw with lime

Coquette’s eggs

Bircher muesli

Scrambled tofu with pesto and spinach

Lemon and ricotta spelt pancakes

Grilled figs with ricotta and thyme honey

Rhubarb compote with orange flower yoghurt and pistachios

Spring lunches

My mama’s baked acorn squash

Crab and fennel salad

Teddy’s lettuce soup

Asparagus soup with Parmesan

Courgette/zucchini and watercress soup

Baby vegetable fricassee

Broad bean/fava salad with pecorino and asparagus

Spring suppers

Sea bass with black olive salsa and baby courgettes/zucchini

Pan-fried orange halibut with watercress purée

Hortense’s fish soup

Crusted rack of lamb for Luke

Chargrilled scallops on pea purée

Turmeric tofu with cherry tomato quinoa pilaf

Chicken stew with green olives

Prawn/shrimp, avocado, grapefruit, watercress and pecan salad

Summer

Summer breakfasts

Cinnamon roast peaches with vanilla yoghurt

Blueberry strawberry smoothie

Cold frittata with goat’s cheese and courgettes/zucchini

Scrambled eggs with watercress and smoked salmon

Breakfast burrito

Home-made muesli with strawberry yoghurt

Summer lunches

Avocado soup

Quinoa salad with tahini dressing

Beetroot soup

Pea soup

Summer squash with tomato sauce and pine nuts

Salad niçoise sans anchovies and potatoes

Fish cakes

Summer suppers

Linguine with tomatoes, lemon, chilli and crab

Warm ratatouille

Chicken and fennel au gratin

Coconut curry with prawns/shrimp

Grilled vegetables with halloumi cheese

Barbequed salmon on a cedar plank

Wild rice risotto

Puddings

Ginger parkin

Baked apples

Lemon Capri torte

Lemon mousse

Clover’s Carnation milk jelly

Blackberry and apple crumble

Flourless chocolate cake

Cardamom rice pudding

Elderflower jelly

Flapjacks

Eton mess with rhubarb

Banana Bread

Chocolate chestnut soufflé cake

Orange yoghurt and polenta cake

Acknowledgements

Index

Suppliers

Copyright

About the Publisher

Cook’s notes

I long to learn about grams and kilograms—perhaps one day I will. Having lived in America for so long, I am used to cooking in American measurements of cups and sticks of butter, etc. However, this book has been cleverly translated so that you don’t have to.

All spoon measures are level unless specified otherwise.

1 tsp = 5ml; 1 tbsp = 15ml. An American tablespoon is slightly smaller than the standard British tablespoon.

A British pint = 600ml; an American pint (2 cups) = 500ml.

All pepper is freshly ground black pepper. I also use good-quality sea salt, such as Maldon.

Eggs/Dairy/Stock/Poultry: try to use organic, free-range where possible. If you are pregnant, avoid raw or lightly-cooked eggs and unpasteurized cheeses. For stock I use either fresh or vegetable bouillon; Marigold Swiss Vegetable Bouillon Powder is very good.

Citrus fruit: if the zest is to be used, buy unwaxed citrus fruit.

Crème fraîche: American readers can substitute soured cream.

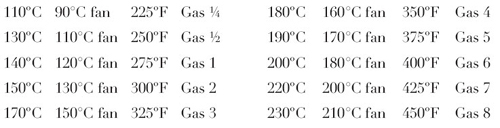

OVEN TEMPERATURE CHART

Oven timings are for both conventional and fan-assisted ovens. However, use oven temperatures and timings as a guide: get to know the temperatures of your own oven, since individual ovens can vary quite a bit.

Introduction

The second word I ever spoke was ‘crunch’—muddled baby speak for fudge, which should have alerted my parents to what lay ahead. As a small child, food occupied both my waking and nocturnal thoughts; I had clammy nightmares about dreadful men made from school mashed potato wearing striped tights, chasing me into dense forests.

A welcome dream was a cloud made of trifle, a slick spring bubbling with chocolate or a fountain bursting with forbidden Sprite or Cherry Coke. My dolls had the fanciest tea parties in London and I kept a tight guest list, so the only person actually benefiting from the tea was me. My first (and last) rabbit was named for my then favourite breakfast food, the pancake. Pancake was a brute, and he performed an unnatural sex act upon his hutchmate, Maple Syrup, who was a docile, blinking guinea-pig. The shock killed Maple Syrup immediately and Pancake was banished to the country to live out the rest of his days in shame and isolation. It seemed unfair that his strange peccadilloes were rewarded with buxom country rabbits and fresh grass, but the karma police intervened and he met a gruesome end in the jaws of a withered fox.

I have always had a passionate relationship with food; passionate in that I loved it blindly or saw it as its own entity, rife with problems. Back in the day, in my esteem, food was either a faithful friend or a sin, rarely anything in between. Eating as sin is a concept more pertinent than ever before in this tricky, unforgiving today. I realized at an early age that I was born in the wrong time, food-wise. I would have been infinitely more suited to the court of Henry VIII, where the burgeoning interest I showed in food would have been encouraged and celebrated. Alas, in my London of the eighties it was simply cause for family mirth, sullen trips to the nutritionist and brown rice diets. Oddly enough, I was reasonably skinny with a great round moon face; just perpetually hungry like a baby bird. I got rather chubby and unfortunate-looking when I was about seven, and there are some rather sinister pictures of me looking like a grumpy old woman (I had a penchant for coral lipstick and any church-type hat), always with a large sandwich hanging out of my mouth.

I grew up surrounded by food lovers; my parents Tessa and Julian were natural cooks and both sets of grandparents were known for a full table. My earliest memories of food involve my paternal grandmother Gee-Gee, (an ex chorus-girl dancer, five foot of endless leg, saucer-blue eyes and marcelled blonde waves) who lived on the Sussex coast in a house surrounded by whispering trees. My dad and I would drive down from London, a journey that felt decades long to a child, but the monotony was forgotten as soon as Gee-Gee swung open the front door and we were embraced; first by a pleasurable blast of something roasting, and then by her. These lunches usually incorporated roasted something with gravy, Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes, parsnips, cauliflower cheese, and definitely puddings: treacle tart with a cool lick of cream to sophisticate and sharpen the sugar, incredible crumbles, swimming in thick vanilla custard. Every day there was proper tea at Gee-Gee’s, with homemade scones, ginger cake and her best bone-thin china. She understood absolutely everything about life, except three things:

1 Why anyone, most specifically me, would become a vegetarian.

2 Why it was difficult for hunger to be limited to three times a day, with a little pang left over for tea, devoid of desire to pick between meals.

3 The attraction of violently-coloured eye shadow to a sixteen-year-old. (‘Like an ancient barmaid,’ she’d sniff at my peacock-feather-green eyelids.)

Gee-Gee was brilliant; she taught me to bake without fuss. I watched the quiet joy she derived from feeding those she loved and I took it with me like a tattoo into adulthood, making idle breakfasts and Sunday lunches, Indian summer dinners and rainy day teas, revelling in the simple pleasure cooking for people I cared about brought me.

If anything, this book is a total homage to my family and the appetite and culinary legacy they left me with: Gee-Gee; my maternal grandmother Patricia of Knoxville, Tennessee, with her fondness for grits, collard greens, and lemon chiffon pie; my Norwegian grandfather, Roald, and his vast appreciation for chocolate, borscht and burgundy; his second wife, Felicity, who in his absence continues to keep his table with the same spirit and standard; my aunts and uncle, fine cooks all; my mum and dad, my brothers and sister; each and every one of them has an influence in here somewhere.

I am not an authority on anything much, but I do feel qualified to talk about eating. I’ve done a lot of it. In my time I have been both round as a Rubens and a little slip-shadow of a creature. Weight, and the ‘how to’ maintenance of it, seems to be something that preoccupies a lot of people, and because I lost some, rather publicly, it is something people feel free to ask me about. I have had conversations about weight with strangers in supermarkets, on aeroplanes and in bathroom queues. I could talk until the cows come home about food and recipes and bodies and why as people we are so consumed by the three. I have sat next to erudite academic types at dinner, steeling myself for a conversation that will doubtless include something I know nothing about, like physics, only to be asked in a surreptitious tone, ‘How did you get thinner?’ At which stage I will laugh and say, ‘Well, it all started like this…’

Autumn

We begin in the autumn because that’s when everything changed. Autumn is a season I love more than any other; for its smoky sense of purpose and half-lit mornings, its bonfires, baked potatoes, nostalgia, chestnuts and Catherine wheels.

It was late September. I was eighteen. I had experienced a rather unceremonious exit from school. I had no real idea about what I wanted to do, just some vague fantasies involving writing, a palazzo, an adoring Italian, daily love letters and me in a Sophia Loren sort of dress, weaving through a Roman market holding a basket of ripe scented figs. I had just tried to explain this to my mother over lunch at a restaurant on Elizabeth Street in London. She was not, curiously, sharing my enthusiasm.

‘Enough,’ she said. ‘No more alleged history of art courses. You’re going to secretarial college to learn something useful, like typing.’

‘But I need to learn about culture!’ She gave me a very beady look.

‘That’s it,’ she said. ‘No more. End of conversation.’

‘But I…’ The look blackened. I resorted to the historic old faithful between teenagers and their mothers.

‘God…Why don’t you understand? None of you understand me!’

I ran out into the still, grey street, sobbing. I threw myself on a doorstep and lit a bitter cigarette. And then something between serendipity and Alice in Wonderland magic happened.

A black taxi chugged to a halt by the doorstep on which I sat. Out of it fell a creature that surpassed my Italian imaginings. She wore a ship on her head, a miniature galleon with proud sails that billowed in the wind. Her white bosom swelled out of an implausibly tiny corset and she navigated the street in neat steps, teetering on the brink of five-inch heels.

Her arms were full to bursting with hat boxes and carrier bags and she was alternately swearing, tipping the taxi driver and honking a great big laugh. I remember thinking: ‘I don’t know who that is, but I want to be her friend.’ I was so fascinated I forgot to cry.

I stood up and said, ‘Do you need any help with your bags?’

‘Oh yes!’ she said. ‘Actually, you are sitting on my doorstep.’

‘So, why were you crying?’ The ship woman said in her bright pink kitchen. It transpired that she was called Isabella Blow; she was contributing editor at Vogue and something of a fashion maverick. We’d put the bags down and she was making tea in a proper teapot.

‘I was crying about my future.’ I said heavily. ‘My mother doesn’t understand me. I don’t know what I’ll do. Oh, it’s so awful.’

‘Oh don’t worry about that. Pfff!’ she said. ‘Do you want to be a model?’

If it had been a film, there would have been the audible ting of a fairy wand. I looked at her incredulously. ‘Yes,’ I said, thinking of avoiding the purdah of shorthand. My next question was, ‘Are you sure?’

‘Now put on some lipstick and we’ll tell your mother we’ve found you a career’

The ‘Are you sure?’ didn’t spring from some sly sense of modesty; it was brutal realism. And not of the usual model standard ‘I was such an ugly duckling at school, and everyone teased me about how painfully skinny I was’ kind.

Bar my height, I couldn’t have looked any less like a model. I had enormous tits, an even bigger arse and a perfectly round face with plump, smiling cheeks. The only thing I could have possibly shared with a model was my twisted predilection for chain smoking.

But for sweet Issy, as I came to know her, none of this posed a problem. She saw people as she chose to see them; as grander cinematic versions of themselves.

‘I think,’ she said, her red lips a post-box stamp of approval, ‘I think you’re like Anita Ekberg.’ I pretended I knew whom she was talking about.

‘Ah yes. Anita Ekberg.’ I said.

‘Now put on some lipstick and we’ll go and find your mother and tell her we’ve found you a career.’

We celebrated our fortuitous meeting, with my now mollified mother in tow, at a Japanese restaurant in Mayfair, toasting my possible new career with a wealth of sushi and tempura.

‘Gosh, you do like to eat,’ Issy said, eyes wide, watching as my chopsticks danced over the plates. I would have said yes but my mouth was full.

Social activities in England often revolve around the tradition of the nursery tea. I was deeply keen on tea, but as an only child I was not at all keen on having to share either my toys or my food.

‘You must learn to share. It’s a very nasty habit, selfishness,’ Maureen, my Scottish nanny said, her grey eyes fixed on me in a penetrating way.

‘Urgh. It’s so unfair!’ I would cry, scandalized by the injustice of having to watch impotent as other children, often strangers, were allowed to torture my dolls and eat all the salt and vinegar crisps for the mere reason that ‘they can do what they want—they are your guests.’

But I didn’t invite them! You did. I don’t want them messing up my dressing-up box and smearing greasy fingers on my best one-eyed doll, or asking to see her ‘front bottom’. I don’t want friends who say ‘front bottom’. I want to play Tarzan and Jane with Dominic from next door, who has brown eyes and kissed me by the compost heap. I don’t want to be the ugly stepsister in the game, I want to be Cinderella! No, I’m not tired. I might go to my room now and listen to Storyteller. They can stay in the playroom on their own.

When I was six, my friend Ka-Ming came for tea. There was macaroni and cheese, and for pudding, yoghurt. Maureen announced in her buttery burr that there were only two yoghurts, chocolate and strawberry, on which Ka-Ming, as the guest, got first dibs. Agonizing as Ka-Ming slowly weighed up the boons of each flavour, I excused myself and ran to the playroom, where the wishing stone my grandmother Gee-Gee had found on the beach sat on the bookshelf. I had one wish left.

‘Please, wishing stone and God, let her not pick the chocolate yoghurt, because that is the one I want.’ I cradled the stone, hot in my palm.

I walked into the kitchen to find Ka-Ming already eating the strawberry yoghurt with enthusiasm. The chocolate Mr Men yoghurt sat sublime on my plate. This turn of fate cemented my belief that if you wish for something hard enough, as long as it doesn’t already belong to somebody else you tend to get it.

At ten, to my great dismay, I was sent to boarding school. I recalled the permanent midnight feasts in Enid Blyton books, and reckoned that this was the sole pro in an otherwise dismal situation. Yet on arrival I realized that the halcyon midnight feasts were a myth. The reality was fried bread swimming its own stagnant grease, powdered mashed potatoes, bright pink gammon, gristly stew, grey Scotch eggs and collapsed beetroot, which I was made to eat in staggering quantity.

The consolation prize when home from boarding school was picking a Last Supper. Last Suppers were cooked the final night of the school holidays by my mother at her bottle-green Aga; a balm to the palate before another term of unspeakably horrible food. I chose these suppers as if I was dining at the captain’s table on the Titanic—beef consommé, roast chicken wrapped in bacon with tarragon creeping wistfully over its breast, potatoes golden and gloriously crispy on the outside and flaking softly from within, and peas buttered and sweet, haloed by mint from the garden. Puddings were towering, trembling creations: lemon mousse, scented with summer; chocolate soufflés, bitter and proud.

We were grumpily ambivalent about the food at school; the English as a rule aren’t a race of protesters, particularly the ten-year-olds. School food was meant to be bad, that was its role before the advent of Jamie Oliver and his luscious organic, sustainable school dinners. There was the merest whiff of protest during the salmonella crisis in the late eighties, when some rebel chalked ‘Eggwina salmonella curry’ over the curried eggs listing on the menu board and got a detention for their efforts, but that was about as racy as it ever got.

I left boarding school at twelve, and we moved from starchy London to svelte New York. It was in this year that food first became something other than what you ate of necessity, boredom or greediness. I noticed that food contained its own brand of inherent power, certainly where adults were concerned. Women in New York talked about food and how to avoid it all the time. Their teenage progeny religiously counted fat grams, while the mothers went to see a tanned diet guru named Dr R, who provided neat white pills and ziplock bags for snacks of mini pretzels, asking them out for fastidious dinners where he monitored their calorie consumption. If they were lucky they might get a slimline kiss at the end of the evening, the bow of his leonine head offering dietary benediction. It was a savvy way of doing business; Dr R had a repeat clientele, as all the divorced mums were in love with him, staying five pounds over their ideal weight in order to prolong both that coveted dinner and his undivided attention.

I loved New York, loved its fast glittery shininess and sophistication, which was the polar opposite of the dowdy certainty of English boarding school. At my new school, my ineptitude with maths was greeted with such bolstering and enthusiasm that, for a brief blissful period, I was almost good at it.

In our biology class we read about the perils of anorexia. We learnt the signs to be wary of: secrecy, layers of clothing, blue extremities, pretending to have eaten earlier, cessation of menstruation, hair on the body, compulsive exercise.