Полная версия

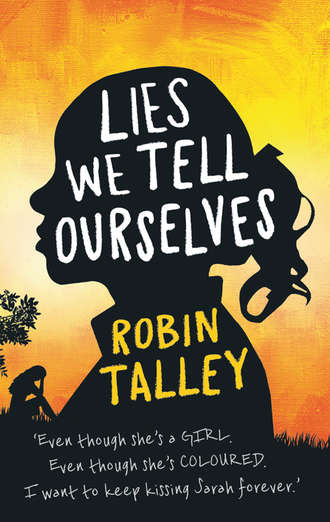

Lies We Tell Ourselves: Shortlisted for the 2016 Carnegie Medal

“Girls, hush,” Mama says. “Your father needs to concentrate.”

“Sorry, Daddy,” Ruth and I murmur toward where our father is perched on the ledge of the living room window.

There’s a loud bang. “Dang it,” Daddy says. He hammered his finger again.

“We still need to close the gap on this end, Bob.” Mr. Mullins hefts up the other end of the last piece of plywood. It’s barely light out yet, but already they’ve nearly finished covering all the first-floor windows on the front of the house. For the first ten minutes they were working Bobby kept wandering around asking why they were making so much noise, and could he help Daddy play workshop. Mama finally told him to go to his room until it was time for school.

Ruth and I didn’t ask why they were putting the boards up. We didn’t ask why Mama brought down the basket of old clothes from the attic and told us to mend them, either. We knew we’d be wearing our old clothes to school from now on in case they get ruined. We knew Daddy and Mr. Mullins were putting boards on the windows in case the white people threw rocks when they drove by the house.

There’s no use talking about these things. These things just are.

Mama snips a piece of thread, then looks at the map I’ve laid out on the breakfast table next to our sewing. “You’re sure this is necessary, Sarah?” she says.

I look at her. She looks back, then lowers her eyes.

I don’t know if this will work, but I’ve got to try.

School is worse than I thought it would be, but I can survive this. And I’m going to make sure Ruth survives it, too.

As long as I have my dignity, I can do anything.

Last night I took Ennis’s sketch of the school and Ruth’s class schedule and I drew a map to follow through the day. I’ve already figured out how I can check in on Ruth after Homeroom and before third period, but our lunch periods are staggered, and I’m having trouble figuring out a way to get from the basement to the second floor and back without being late for Home Ec.

I can’t be late to class again. I’ve already got detention after school today, thanks to Mrs. Gruber. Ruth will have to leave school without me. That’s not a risk I ever want to take again.

I barely slept last night. Instead I lay there for hours, listening to Ruth tossing and turning in the next bed, murmuring in her sleep. High-pitched cries, the kind she used to make when we were little and Mama tried to make her take her stomach medicine.

I must’ve fallen asleep sometime. Because I remember dreaming.

In the dream it was still yesterday morning. I was trying to get across the school parking lot, holding Ruth by her arm, but instead of walking, we were running. A monster as big as a city bus was chasing us. It had deep red scales, a thumping, clubbed tail and glistening huge white eyes. Ruth and I were trying to get inside the school, where we’d be safe, but once we’d finished the sprint across the lot and made it through the front doors, the monster kept coming. Then there were more monsters, and more. Soon a whole herd of them was thundering down the hallway behind us. We kept looking for a way out, but every time we turned a corner it led to another hallway, endless rows of gleaming lockers and polished floors.

Ruth was pulled from my grip. I screamed. When I turned to look for her, Linda Hairston was standing in Ruth’s place. She smiled at me, her pretty red hair glistening under the fluorescent lights, just like the monsters’ scales. Linda threw back her head and howled. Her laughter was so loud and fierce the monsters stopped chasing us and started laughing with her.

“You be careful today,” Mama says after we’ve changed into our mended clothes and gathered our things to meet the carpool. “Even with the new rule, you make sure and keep a watch out.”

“We know, Mama,” Ruth says, wiping off her cheek after Mama kisses her.

Mrs. Mullins called us late last night to tell us about the new rule. The principal had just announced it. When the gray-haired teacher reported what happened to Yvonne, the principal decided no one could be punished because no adult saw who’d instigated it. So from now on anyone who got caught fighting—no matter who started the fight—would be expelled.

Ruth whooped when Mama told us the news. Mama and I just frowned at each other. Somehow we didn’t think it would be as simple as that.

Mama puts her hand on my shoulder as I’m going to the door.

“Remember what to do when it gets hard,” she says. “Take your worries to the Lord. Have faith. He’s watching over all of you.”

I nod. Mama’s right, of course.

But I can’t help wondering why the Lord has to watch over us from so far away.

* * *

New rule or not, today is no better than yesterday.

We go in the side door this time, like Ennis planned, but there are just as many white people waiting for us there. The police aren’t here today, but that doesn’t seem to make a difference. The white people throw sticks past our heads and shout as loud as ever. That must not count as fighting, because no one gets expelled that I hear about.

I’m still not used to being called “nigger,” but I’ve stopped keeping track of how many times I hear it. Instead I count the minutes left in the school day. I watch the hands of the classroom clocks wind their way around until I’m free of this place and the people in it.

In Math someone’s brought in extra desks for the back of the room. Now everyone has a seat without having to get anywhere near Chuck and me. Chuck draws a picture in his notebook of Mrs. Gruber standing in front of a classroom full of tanks and soldiers firing on each other. The Mrs. Gruber in the picture, who’s twice as fat and three times as ugly as the real Mrs. Gruber, has her eyes squeezed shut and fingers stuck in her ears. A comic-book speech balloon has her singing, “LA LA LA I CAN’T HEAR YOU!!!” When Chuck shows it to me I almost smile.

Adults always tell us education is the most important thing in life, but I’m not learning anything at Jefferson. It’s supposed to be the best school for miles around, with the best facilities and the best teachers, but none of that is doing me any good. Our science labs at Johns weren’t as nice as the ones here, but when I was at Johns I could focus on my schoolwork. I didn’t have to spend every moment looking over my shoulder to see what would be thrown at me next.

In History I overhear two girls gossiping about something they heard from their friends. According to their story, one of the Negro girls (only the girl telling the story calls her a “nigger girl,” in the giggly whisper of a child who’s trying out a naughty word for the first time), went up to a white girl in the locker room this morning and told her she smelled like cow shit and looked worse. The white girl told her boyfriend, and he told his friends. Now the boys are saying they’ll “get that nigger back” later today.

The gossip can’t be true. None of the Negro girls in our group would ever do such a thing. None of them would use that kind of foul language. Besides, Mrs. Mullins has told us a thousand times not to talk back to the white students. I can’t stop remembering what Yvonne looked like yesterday, though, huddled in a pile in the hall. When school lets out today, I’ll make sure to keep every single one of these girls someplace I can see them until we get safely home.

When I get to Typing, the teacher points out a typewriter she’s set aside in the far corner for me and the Negro girls who take Typing in other periods. The teacher smiles, like she’s waiting for me to thank her. And I do it. I grit my teeth, but I still say, “Thank you, ma’am,” sweet as sugar.

As I drop my purse on the desk I see something tucked under my typewriter. One of the white girls must have left it there. It’s a clipping from the Davisburg Gazette. I didn’t see the paper this morning—Mama had already put it away somewhere—but this front-page story is headlined Negroes Integrate Jefferson High. Two School Board Members Resign in Protest. Under the headline is a photo of the ten of us. Someone has drawn a circle on the photo in lipstick, right around my face, and put a big red X over it. Scrawled black ink in the margins says “DIE UGLY NIGGER.”

I swallow, glad I have my back to the rest of the room so the girls can’t see my face. I start to crumple up the paper when I see a sidebar with the headline Jefferson Students Speak Out. One of the reporters who blinded me with his flashbulbs yesterday must’ve talked to some of the white students afterward. The first quote in the story is from Linda Hairston.

“‘What about our right to an education?’” Linda’s quote reads. “‘No one talks about that. The colored people aren’t the only ones who should have rights.’”

Yesterday I’d thought Linda Hairston was smart.

I crush the paper in my fist, march to the front of the room and throw it in the trash can. On my way back I fold my arms across my chest so no one will see my hands shaking.

During each class break I walk as fast as I can, following the routes I mapped out at breakfast. I see Ruth every time, and every time, she’s all right. There’s a new ink stain on her blouse that wasn’t there this morning, but she isn’t hurt. She’s just walking down the hall surrounded by a circle of white people, clutching her books and pretending not to hear the chants of “nigger, nigger, nigger” that follow her everywhere.

The white people follow me, too, slowing me down. It doesn’t matter what route I take. They walk behind me and in front of me. Trying to trip me, calling out to me, stepping on my heels, blocking my path. It’s like walking through quicksand.

When I leave third-period History, trying to forget what that awful Mrs. Johnson said in her lecture about the slave trade, there are still two hundred and thirty-five minutes left in the school day. I speed toward the stairs to get to Ruth, uncertain of how I’ll get back to the second floor in time for French.

It isn’t the distance that’s the problem. I could walk there and back easily if the white people would only leave me alone.

But they won’t. In fact, there’s a group of white boys following me as I exit the staircase and start down the first-floor hall.

They’ve been behind me since History. I don’t have to look back to know they’re still there. The feeling of eyes on my back is familiar by now.

But there’s something different about this time. These boys are being quiet. They aren’t chanting, or calling me names or joking with each other. Occasionally one of them will snicker, but the others quickly hush him.

When I’m halfway down the hall, they’re still following, silent except for their thudding footsteps. From the sound of it there are at least ten of them. People coming the other way wave at the boys as they pass, smiling and calling to them.

The boys are getting closer.

I speed up, but their footsteps get faster, too. There’s no way I could outrun them.

They must be planning something. I hope they get it over with soon. I brace myself for the feeling of an object striking my back. A wad of spit, a pencil, a rock they snuck in from outside.

Nothing comes.

Something’s wrong.

The voice in my head is certain. I don’t know what’s happening, but I know it’s something new. Something bad.

I speed up, but the shuffling footsteps are louder now. One of the boys is right behind me.

The pain comes with a jolt. I freeze. My breath stops, and my voice catches in my throat. The shock of it is too strong.

The boy is squeezing my breasts, hard.

He lets go as fast as he grabbed on, and then all the boys are running past me at once. Laughing. Trading high fives.

There’s no way to know which of them did it.

The crowd coming the other way has stopped moving, too. They’re pointing at me, laughing. The girls are covering their mouths to hide their giggles.

I cross my arms over my chest, but that only makes them laugh harder.

That really just happened.

That boy touched me. I didn’t want him to, but he did it anyway. That was why he did it. Because he knew I didn’t want it.

Nothing is mine anymore.

Even my own body isn’t mine. Not if that pack of white boys doesn’t want it to be.

Everyone saw what they did.

It’s exactly like my dream. The pack of monsters, laughing.

I drop my head so they can’t see my face. I would never let someone do that to me. I’m not the sort of girl who would ever do anything like that.

The white people at this school don’t care what sort of girl I am.

I look down at myself. I don’t look any different than I did this morning. What the boy did hadn’t left a mark. But nothing will ever undo it.

My dignity was all I had.

Tears well in my eyes. The pack of boys is all the way at the end of the hall now. One of them, a tall brown-haired boy, is still looking back at me, grinning, but the rest are looking at something up ahead.

“That’s her,” one of them calls. “That’s the nigger who talked back to my girl.”

“Big Sis still back where we left her?” another boy answers. His voice carries all the way down the hall. They don’t care who hears them.

“Yeah,” the other boy says. “We scared her off but good.”

“Let’s go, then.”

I recognize the brown dress. The one she was mending this morning.

It’s Ruth they’re running toward.

She’s the one the story was about. The one who talked trash to a white girl.

My shoes feel like lead. I run, my legs pumping as hard as they can, but I’m not fast enough.

“Stop it!” I shout. It comes out as a screech. The white people gathered on the sides of the hall are still and quiet, watching.

The boys have caught up with Ruth. They’ve got her in a corner where she can’t back away. I’m still too far to see her face, but I can picture the fear in her eyes.

“Leave her alone!” I scream, but the crowd has gotten noisy again. No one hears me.

I don’t care about the rules anymore. I’m not going to ignore what’s happening.

I tear down the hall after them.

But I can already tell I’m going to be too late.

Lie #8

THEY CANCELED THE prom today.

Because of the colored people. Everything that happens now is because of the colored people.

If Daddy has to work late at the paper it’s because the integrationist teachers are making up stories. If I’m behind in English it’s because the NAACP forced the school to close last semester. If I get caught daydreaming in Math it’s because the colored girl in the front row distracted me.

But the prom? Why did they have to get that, too?

I was going to the prom with Jack. It was going to be my last date of high school, and the first time Jack and I went to a dance together. Jack is far too old for these sorts of things—he’s twenty-two—but he said he’d come anyway. He said I shouldn’t have to miss out on my own prom just because my fiancé is an older man who’s long past childish stuff like school dances.

“I don’t see why they had to cancel in the first place,” Judy says. She has to raise her voice for me to hear her. There’s noise up ahead. People shouting. There’s always shouting in the halls now that the colored people are here.

We’re walking down the hall toward the first-floor bathroom near the stairwell. It’s the only bathroom Judy ever wants to go in because it’s always empty and she can fix her makeup without anyone seeing. The toilets in that bathroom have been stopped up since our freshman year.

“It’s obvious,” I say patiently. You have to be patient with Judy. She’s not slow like people think. She’s naive, that’s all. “No one wants white people and colored people dancing together.”

“Would that really happen?” Judy says. “Was someone going to force us to dance with them? Wouldn’t the coloreds only dance with each other?”

“Coloreds isn’t a word,” I tell her for the hundredth time. I swerve to step around a group of giggly sophomores. People are so rude, blocking the halls like this. They think just because our school is integrated they all have the right to act like animals.

“Right,” Judy says. “Sorry. The Nigras, I meant. But wouldn’t they?”

“Who knows what would happen,” I say. “No one thought we’d be forced to let them into our school. It’s not as if they didn’t already have their own. If they weren’t happy going to school with each other, why should they be happy dancing with each other?”

“Oh,” Judy says. “I hadn’t thought about it that way.”

I picture the shiny blue dress in my closet. It’s strapless, with a matching blue wrap and blue high heels. It looks almost as good as the fancy one from Miller & Rhoads I modeled in the Future Business Leaders of America fashion show last year. Mom took me shopping for it the day they announced the schools were going to reopen. She said it was too bad about the integration, but at least I wouldn’t have to miss out on all the fun of my senior year.

Daddy was furious when he found out. He said I wasn’t going to any dance with any colored boys. I told him I wasn’t going with a colored boy, I was going with Jack, and besides, it wasn’t my fault the governor gave up on segregation. Daddy said as long as I was under his roof I would speak to him respectfully, and I said then it was a good thing I wouldn’t be under his roof much longer. Then he pulled back his hand. For a second I thought he was going to do it. I think he thought so, too.

I almost wanted him to do it. To prove I still mattered to him even a little bit.

But he didn’t. He put his hand down and said I was an ungrateful little girl and he had work to do. Then he went to his study and didn’t come out again all night. As though he’d forgotten I was out there.

Mom told me to keep the dress because you never knew. Daddy had been known to change his mind about things. Then she disappeared upstairs with a glass of sherry and I was alone again.

The noise is getting louder as we near the stairwell. “We’re gonna shut that nigger up!” a boy yells.

Oh, for heaven’s sake. This again?

“That looks like a colored girl they’ve got there,” Judy says. The shouting is so loud I have to strain to hear her.

“A girl?” I say. “Who’s got her?”

“Bo and his gang, I think.”

I could’ve guessed. Bo Nash and his friends are a bunch of nobodies. Or they would be, anyway, if Bo hadn’t scored two touchdowns back-to-back sophomore year. He went from no-good redneck farm boy to town hero in one night. It only got worse that spring, when he pitched a no-hitter for the baseball team’s state championship. Girls stopped joking about Bo’s dirty, mismatched socks and started cooing about his dreamy blue eyes. It was enough to make you vomit. Now Bo thinks he owns the school. And everybody else seems to think so, too.

Well, not me. Any boy who wants to beat up on a girl, colored or not, isn’t worth the sweat in his undershorts. Bo’s a star of the team, so I can’t be outright nasty to him—not unless I want to hear everyone whispering about me in the halls all year—but I can take him down a peg or two.

Bo is right up in front of the colored girl when I get there. He and his friends have got her backed into a corner. She’s turning her head this way and that, looking for a way out. It’s one of the younger ones. Her white blouse has an ink stain on it, and her brown skirt is old and patched.

I stride up to the group and step in neatly between the boys and the girl, facing Bo. He scowls at me. Behind us, people are yelling, and another girl is screaming. I hold out my hands the way Reverend Pierce does when he’s trying to get an especially rowdy congregation at Davisburg Baptist to sit down and be at peace already.

“What’s the matter, Bo?” I ask, raising my voice so everyone can hear. “You’ve got everybody all riled up. For a second I thought Elvis came to town.”

A bunch of people laugh. I smile, because I know it’ll make Bo mad. I haven’t forgotten what he said to Judy in French yesterday. If he thinks he can get away with treating my best friend like that, he’s even dumber than I thought.

“You best just get on out the way, Linda,” Bo says. “We’re teaching somebody a lesson.”

I look over my shoulder in fake surprise, as if I didn’t know the colored girl was there. She’s cowering against the lockers. I take my first good look at her. Her eyes are wide and shockingly white around her deep black irises. The sleeves of her blouse have been let out so far the frayed edges are showing. She probably lives in one of those falling-down shacks out in Clayton Mill. My brothers say those places are full of lowlifes and it isn’t safe for a girl like me to go near them.

The colored people are all poor as dirt. They look it and smell it, too. Everyone says so.

I turn back toward Bo. “Right,” I say. “Because picking on some dumb, dirty little colored girl takes you and twenty of your friends.”

There’s more laughter behind Bo. The girl who was screaming before has stopped, thank the Lord. Everyone is watching me.

“She talked down to Gary’s girl,” Bo says, nodding toward the black-haired boy behind him. “She needs to learn her place.”

“Gary has a girl?” I’d heard that—Gary started going out with that freshman Carolyn, because everyone says she’ll go all the way with anyone who gives her his football pin—but I pretend I haven’t. “That’s really nice, Gary. Maybe we can double-date sometime.”

“Well, sure, Linda,” Gary says, smiling as if it’s a sunny Sunday afternoon, and there isn’t a scared little colored girl hiding behind me in the hallway. All the boys on the team want to go on double dates with Jack and me. “That’d be swell.”

Bo isn’t smiling.

“I’m not joking around, Linda,” he says. “You got to get out of our way. I don’t like to push a girl, but—”

Unless she’s a colored girl, apparently. I lower my voice so only Bo can hear. “I’m sure you didn’t just threaten me, Bo. Because if you did, you know Coach Pollard will hear all about it.”

Bo cocks his head to the side. His face slackens. I’ve won.

I raise my voice again.

“I thought you all might like to know Principal Cole is right around the corner,” I lie. “I saw him on my way from English. Maybe you don’t care, but I just figured I’d mention it...”

The boys back away. Everyone knows the new rule about fighting. No one’s talked about anything else all day.

My father thinks the rule is absurd. He told Mom and me all about it last night. He’ll have an editorial out tomorrow about how we need to teach our children personal responsibility, instead of harshly disciplining boys for being boys. Once the people of Davisburg have read what he has to say, he told us, he expects the policy to be reversed promptly.

“Don’t you do that again, Linda,” Bo says under his breath before he fades away with the rest of his group.

“Aw, Bo, I’m just teasing,” I reply, just as low.

I hope he believes me. I don’t have a bit of respect for Bo Nash, but he’s not someone you want mad at you, either.

When I turn around, the little colored girl is gone. I guess she went to her class. We only have two minutes left before French, but Judy still needs to do up her makeup, so we go into the bathroom.

Judy scrubs her face clean, grabs her compact and gets to work, moving so fast she’s going to leave streaks. I’m about to tell her to fix it when the door bursts open and a girl rushes past us and crouches on the floor. It’s another colored girl.

Judy drops her compact she’s so shocked. I’m surprised, too. We used to come in this bathroom between classes every day last year, and not once did anyone else come in.

“What are you—” Judy says, but I hold up my hand for her to let me handle this.