Полная версия

It’s About Love

“He couldn’t handle you seeing him, you know?”

And, just like that, there’s a tiny crack in the wall of him.

I can’t help staring. “What?”

Dad won’t look me in the eye, but he carries on. “He made me promise not to bring you, for visits. Your mum too. He didn’t want either of you seeing him in there. Me either. That’s why I stopped going.”

It’s the most he’s said about Marc since he’s been away and I don’t know where to look. Our road is dark and quiet.

“I told him. I told him, Luke. One’s enough. One good punch and walk away. One …” He breathes through his nose like an animal. “Him who can’t hear, must feel. Eh son?”

I say nothing. Just sit next to my old man, feeling more like a grown-up than I ever have.

Dad shifts in his seat. “Anyway, that chippy’ll be shutting. I’ll see you, Lukey.” And the moment’s over and I’m about to get out, when he grabs my head with his big hand and pulls it towards him, kisses me on the crown, then pushes me off. “Go on, get home.”

I watch the car drive away, the red brake lights as it reaches the corner, then it’s gone. One small scene. The least amount of words, but it feels like somebody just lifted up the heavy rock of my dad and showed me something growing underneath.

I’m walking up the hill to college. It’s Tuesday.

I’ve convinced myself that ‘brooding loner’ is my persona of choice. I’ll find a different seat in film, and if there isn’t one, I’ll just style it out and keep quiet till Leia gets the picture.

As I get to the campus, my phone beeps. It’s a message from Tommy:

Yo, hurry up and hook me up with one of them posh girls, Lukey, don’t be tight. T

I picture him sitting on a stack of paving slabs, smoking a cigarette in between middle-aged builders with thick necks and rubbish tattoos as I type a reply:

Sorry mate, they’re all only interested in me. Animals they are. I’m knackered to be honest. See you tomoz

I read the words and stare past my phone at the floor as I click send.

Groups of people are walking towards different lessons in different buildings and even though he’d probably do or say something to properly embarrass me, I’m wishing Tommy was here right now.

Leia isn’t there when I walk into class, but there aren’t any other spare seats besides the one next to hers so I just sit where I did before, and prepare myself to play it cool. A pale girl with the sides of her head shaved and a ponytail is playing music through her phone to the blonde girl next to her. They both stare at me as I sit down and I make myself not look away. Get a good look if you want.

Noah’s sitting at the front, just watching people as they talk, then Leia walks in with Simeon and I pretend not to notice.

“Hey,” she says, as she sits down next to me. She’s wearing a black Stussy hoodie and it’s probably a birthday present he got her when they were going out or something. Definitely. I nod without speaking and stare forward like I’m ready for the lesson to start. I watch Simeon slap palms with the chunky rugby boy as he sits down and I try and give him a nosebleed with my mind.

Just forget them.

Noah slams his hands down on his desk and everyone jumps.

He stands up slowly and turns to the whiteboard. He’s acting differently, like he’s waiting for something, and pretty much everyone’s eyes are trained on his back as he pulls out a marker and starts to write.

He does a big letter S, then a capital H. A couple of people look at each other, then back at him. As he starts the straight line of an I people are starting to chatter. Noah steps back from the board without turning around and holds his arms out like a conductor.

What’s this guy doing?

And it shouldn’t be a big deal really, a teacher about to write the word SHIT on a board, but it feels like we’re all breaking the rules together. Then Noah steps forward and curves the I round and up into a U and writes SHUT UP. And everything’s quiet. He turns round and he’s smiling and I’m thinking, right now, that must feel amazing.

“You hear that?” he says. People are looking round, out of the window and shaking their heads. My eyes don’t leave him.

“Somebody just fell in the shower.” He tilts his head slightly as though he’s listening for it himself. “You hear it?” He raises his index finger.

People don’t know where to look, but I’ve played this game. I still play this game all the time on my own and I like him. I like you, Noah.

“No one?”

He’s starting to look a bit let down. Nobody else even seems like they might be getting ready to speak. Then my hand goes up. What are you doing?

“I heard it.”

Get your hand down now.

But I just keep it there, as everyone’s eyes turn to me. Noah cracks a smile. “Thank you …” He’s leaning forward, waiting for me to say my name.

I lower my hand. “Luke. My name’s Luke.”

I can feel Leia looking at me on my right, but I stay with Noah. He nods. “Good. Now the real question is, Luke, are they dead?”

And it’s like the scene is ours. Me and him with an audience either side of us. Simeon’s staring back, but I don’t care. This is why I’m here. What? This is why I’m here.

“No. He’s not,” I say, and my blood is electric.

“Ah,” says Noah, “so he’s a he?”

And the room is gripped and I can feel ideas flicking through my head like holiday photos in fast forward.

“Yeah, he’s a man. A young man, and he’s not dead, he’s just lying down.”

As the words come out of my mouth I picture Marc, curled up on his side in a white shower cubicle, like Michael Biehn at the start of Terminator, steam rising as water falls on him.

The girl with the shaved head frowns. “That’s stupid.”

People look at her. I stay on Noah, as he says, “Is it?”

“Yeah,” says the girl. “Why would somebody just lie down in the shower?”

Noah looks at her. “And that’s why it’s brilliant.” He points at her with one hand and at me with the other. “Because you want to know.”

My throat’s dry as I swallow, but I feel great. He said my idea was brilliant.

Then Leia speaks. “It’s what he does.” All eyes move to her.

I turn in my seat. She’s leaning forward, like she’s getting ready for a race. I stare at her mouth as she says, “He waits until his family have gone to work and then he runs a shower and he lies underneath it in the bath. It reminds him of the rain.”

Then she’s looking at me with those dark shining eyes and I’m looking back at her and it’s so clear. There’s something there. There’s definitely something there.

“Amazing!” Noah’s clearly excited. “You two have to work together.”

No wait … Brooding loner, remember?

But then Noah claps his hands and says, “OK, everyone! Pair-up and wait for your sound. Find your character. Start where it matters. In a moment where things hang in the balance. Show us that moment, offer us a question that we need to know the answer to. I’ll come round and hear ideas. Ready? OK. Go.”

For nearly an hour we talk ideas.

I suggest something, Leia listens, then she gives an idea and I respond, and back and forth again and again as we build up our character and his backstory together. Her ideas are brilliant, and the whole time we’re talking it’s like I forget everything else as I just watch this story we’re creating grow out of nothing on the table in front of us.

By the time Noah works his way round to us we’ve got a sketched-out scene and both of us are charged.

“Come on then,” he says, squatting down in front of our desk. His eyes are excited.

I look at Leia, she looks at me. “You wanna start?”

“No, you can.”

And her face lights up. “OK, so it’s morning, right, Luke?”

I nod. Noah watches her.

“So it’s morning, late morning, like half eleven or something, and he’s lying down in the shower. It’s a bath actually, one of those cool free standing ones with the feet and there’s steam as the shower’s raining down on him. He’s nineteen.”

“What’s his name?” Noah asks and we realise at the same time that we didn’t give him one.

I hear Marc’s name in my head. Then Leia says, “Toby. His name’s Toby.”

Noah nods. Leia carries on. “OK. The house is empty. His dad’s at work and his younger sister’s at college. She’s nearly seventeen.”

She uses her hands as she talks, like Mum does, and it hits me that maybe Toby is her brother’s name in real life and if she’s using real details then he’s the same age as Marc.

“So he’s a scientist. Physics, actually, and he’s working on a really complicated theory. The shower helps him think.” My stomach’s dancing as she speaks and my pen rings a circle round her email address that she scribbled on my pad.

Noah frowns, but in a curious way rather than unhappy. “Where’s Mum?” he asks.

Leia taps her pad with her pen. “She left, but when Toby was little, she used to have baths with him. They used to sit in the bath together and put the shower on and pretend it was raining. It’s a good memory, like his happy place, and now it’s his best place to think.”

Did her mum leave?

Noah’s eyes are narrow, like he’s following her train of thought. “I see. So it’s like his connection to Mum, even though she’s gone?”

Leia nods. “Yeah. Exactly. It gives him clarity.”

“I like it,” says Noah, then he looks at me. “And what’s this theory then?”

I glance at Leia and clear my throat. “Time travel.”

Noah’s eyes widen and I feel my face smiling. “Time travel?”

“Kind of. Not backwards in time, that’s not possible, but he thinks he might have figured out a way to see into the future. Maybe.”

Leia cuts in. “We’re not sure yet. He’s like this super brain, but kind of a recluse. He finished his first degree when he was fourteen.”

“And he has these dreams,” I add.

I made the dreams bit up on the spot and look at Leia nervously, but she nods with wide eyes to let me know she’s cool with it and for some reason I feel the urge to hold her hand. I don’t, obviously. Then it’s the end of the lesson.

Noah stands up and scratches his chin like he’s thinking and I don’t want this to be over. Leia looks up at him. “What do you think?”

The pair of us watch him. He slides his hands into his pockets and I can see the muscles in his upper arms through his thin cream shirt.

“I think it’s brilliant.”

And I laugh, out of nowhere, like a fat HA!

What was that? I feel myself shrug, but it’s all right because Leia’s beaming. Then Noah says, “I think you’ve got something here. Something to run with. Well done. Keep working on it together, yeah? You’re obviously a great team.” And I feel myself straightening up in my chair.

“We will,” says Leia.

I start to pack my bag and I’m glowing, like I just won a race.

Then Simeon is standing in front of our desk. “How lame was that?” he says, and my glow flicks off, like the bulb just popped.

Simeon’s rolling his eyes and pointing with his head towards Noah at the front of the class.

“What’s this guy’s thing for picturing people in the shower? What a perv.” He forces a laugh and I feel my shield coming up.

“Lame?” says Leia. “That was amazing! Wasn’t it, Luke?”

And even though it was, even though it was easily the best lesson I’ve ever had in my life, and even though she’s looking at me knowing that we just shared something that felt sort of magic, I just shrug.

“Dunno.” And I get up and leave.

Good lad. Keep it cold.

Sometimes I feel like I could turn myself inside out. Concentrate my mind, tense every muscle, and burst my skeleton out of my skin. One total action and then done. Let everything out and explode. Sometimes I feel like I could do that. Push the detonator and make a massive mess for other people to clean up.

But whenever I think it, the voice in my head tells me I’m all talk.

“What the hell was that?”

Leia’s walking after me as I head down the hill. I don’t turn around.

“Oi, wait up a second!” She moves round in front, facing me. I carry on. She walks backwards and it’s almost like we’re dancing.

“You’re in my way.”

She doesn’t move. “What’s wrong with you?”

And I think about the scene in Goodfellas, when Karen comes looking for Henry after he stands her up and she’s angry and shouting at him and his voiceover is describing the spark in her eyes.

Leia stops walking and I have to stop so I don’t walk into her. I look straight at her. “What do you want?”

“What do I want? We’re supposed to be working together!” I see three boys walking up the hill on the other side of the road. They’re looking at us.

“Stop shouting, man.”

And she instantly gets more angry. I can see her jaw tensing and her right eye is kind of twitching. “I don’t know what your problem is, but we’ve got work to do.”

“Why don’t you just work with Simeon?” And as I say it, I realise how pathetic I sound.

“What?”

“Forget it.” And I step around her and carry on to the underpass.

Leia skips after me. “What’s Simeon got to do with anything?”

And it’s like we’re in Hollyoaks or something, and I just want to press rewind and not open my mouth. Things go darker as we walk into the underpass and the strip lights make it feel even more like a staged scene.

“Luke. What’s the matter? What’s your problem with Simeon?” Her voice is soft and confused and I wanna hit myself. I want to bury my fist into my own face.

I shake my head. “I don’t give a shit about Simeon. I don’t even know Simeon. I don’t even know you.”

She’s looking right at me now, trying to work me out.

What’s she staring at?

“Forget it,” I say. I start walking away faster and feel the disappointment as Leia doesn’t try to keep up.

“So you don’t want to work together?” she calls after me. I turn back and she’s just standing there, wide shot, framed by the underpass entrance, looking at me and I hate the fact that she can’t just read inside my head. I’m an idiot. I know I am, but there’s something here. Between you and me. I’ve felt it. Just gimme a chance.

Why can’t she do that? Why can’t I say that? I want to. But instead I say:

“I’m gonna do my own idea. By myself.”

Then I turn and walk away.

I used to watch the girl next door wash her BMX.

From Mum and Dad’s bedroom window she couldn’t see me.

Every Sunday morning, she’d wheel it out on to the dirty slabs by their back door, flip it over and clean it with a toothbrush.

Her name was Becky.

Something about the way she moved, the care she took, mesmerised me.

I wanted to tell her, let her know I thought she was amazing.

So I wrote her a note, on Dad’s yellow pad, and posted it the day we left to go up and see Uncle Chris in Yorkshire.

The two weeks we were away I thought about her every day. Yorkshire was so boring. Dad and Uncle Chris fixing old bikes. Marc cooking with Mum. There was nothing to do but walk in the wet fields and think about Becky. Her face as she opened the letter. Her writing one back. Me running alongside her as she rode her BMX to the park.

The drive home was all butterflies.

Then we pulled into our road and I saw the SOLD sign straight away. I didn’t even know her house was for sale. Through the front window I could see empty walls and stripped floorboards.

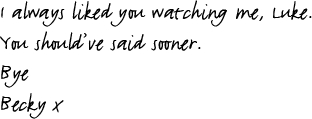

On our door mat, among the post, was a sky-blue envelope with my name on it. I ran upstairs, shut my bedroom door and sat on my bed to read it. All it said was:

I’m on my bed, staring across at my bookcase of DVDs.

My bedside lamp’s pointed up at them like the Twentieth Century Fox spotlight. Mum’s at work at the hospital. It’s just after midnight.

Forget her.

I stare at the DVD spines and picture Leia standing in the underpass, staring confused as I walk away.

Forget her. She’s no different.

But she feels different.

She stared just the same, didn’t she?

My hand comes up to my face. Didn’t she?

My fingertip traces my scar. The curved sickle of torn skin that swoops from above the middle of my left eyebrow, down over my eyelid, across my cheek towards my ear. The glossy smoothness of it. Branding me.

I think about how there’s a version of me, somewhere else, in another universe, without a scar. A sixteen-year-old Luke Henry with a face that isn’t torn, who doesn’t live his life through the stares of strangers. I think about cells. How they die and regenerate and replace themselves and why can’t the cells of a scar be like all the others?

Nan said every scar is the memory of a mistake. A reminder to learn from. I get that. I understand. But do I have to see that memory every day for the rest of my life?

Look at you.

I picture Simeon, head cocked back in laughter, his perfect skin. It’s all so cliché. It can’t be that simple. Surely she can see past it.

What does she see when she looks at me?

Trouble. That’s what she sees. Just like everybody else.

I open my notebook in my lap and stare at the page. Zia’s words from the other day are written at the top: My life is my scrapbook.

My eyes close and my head goes back until it touches the wall behind me.

I use my neck muscles and push back, feeling the pressure in my crown.

“My life is my scrapbook.” Deep breath. “My life is my scrapbook.”

I stare across and read the spines on my top shelf, a jumble-sale mix of films I stole from Dad and Marc and other ones I don’t think either of them have seen; The Conformist, A Room For Romeo Brass, Somebody Up There Likes Me, Buffalo 66.

And then I have an idea.

I’m on my knees pulling out my notebooks. All of them. I spread them out on the floor around me. They’re all A4. Some have scribbled words on the front. Some have doodles and rubbish sketches. One of them has a crude picture of a hand gun in black biro against the brown of its cover. I open it up and flick through, looking for something, then I find it.

We sit opposite each other across the plastic table.

The room has small square windows pushed up near the ceiling and through them it’s afternoon. Spaced out pairs of people all sitting across identical tables from each other. The walls are off-white. A thick-set prison guard stands next to the door. I look across the table at Marc. Nervous. He just stares and says, “You shouldn’t have come.” I want to tell him I wanted to. I had to. He’s my brother. I can help him get through this. But I don’t. I just sit.

Then his skin is changing. Becoming dotted. Grainy. His facial expression doesn’t change, but his skin is becoming sandpaper. Rough and speckled.

“Marc. What’s happening? Marc?”

He doesn’t respond, his skin getting darker and rougher. And then his chin breaks off, the bottom of his jaw crumbling into sand, spilling down his chest. “Marc?” Then his shoulder, like old stone, disintegrates. Then his chest, caving into itself. “Marc!” Then all of him. His neck gives way, then his face, his expression never changing as all of him crumbles away.

I lay the notebook on the floor, open at the page. I can see it. I can see him. And I can use it.

I pick up my new one and I write: Marc

What you doing?

I write Nineteen

What are you doing?

I cross out Nineteen and write Marc. 20 yrs old.

You shouldn’t be writing this.

But I don’t listen. I just carry on.

Marc showers. He dries himself and walks back to his cell. He gets dressed. We can hear shouts and the occasional clank of metal on metal. He folds his towel up and lays it over the back of the chair, watching himself in the small shaving mirror stuck on to the wall above the sink. His dark hair is cut close, light stubble on his top lip and chin, cheeks smooth and fresh. Chiselled.

He stares at his reflection, lowering his chin until it’s almost touching the grey of his sweater, his shoulders rise and fall as he breathes.

Then he speaks. “I’m coming home.”

I’m staring out of the window in comms.

From where we are on the second floor I can just make out the dimpled curve of the Bullring. The teacher lady’s leading a class discussion on immigration and it feels like I’m sitting in the audience on Question Time. An annoying girl with an anime face, dressed fully in American Apparel, has been talking about how disgusting nationalism is and how tabloid newspapers are to blame for most of the lesson. She’s really enjoying having centre stage and I’ve been trying to picture her and Tommy on a date. Him looking confused by the menu as they sit in some posh restaurant, her regurgitating snippets of popular opinion that she’s stolen from blogs.

The girl scans the classroom checking everyone’s paying attention to her and I remember Dad saying that people with the freedom to talk mostly do only that.

“It’s all just fear mongering,” she says, and I imagine Tommy in blue overalls in front of an open furnace, hammering a piece of metal that’s shaped into the word FEAR.

“They use our insecurities about money to whip up hatred,” she goes on.

I look down into my open bag at my notepad and think about how it’s film after lunch.

“What about you, Luke?”

The teacher’s talking to me. Louise. She looks like she might’ve been the lead singer in a band a long time ago. Her hair sprouting out of her head, like blonde fire with dark roots.

“Where do you stand on this?” And a room full of eyes are burning me. My feet are digging into the carpet as I try to look like I have an opinion.

“Where are you from?”

What the hell’s that supposed to mean?

“Birmingham,” I say, and a few people laugh. I can feel the cords in my neck.

Louise smiles and says, “No, I mean your family, originally?”

I look round the room. There’s a handful of other kids who aren’t white, so she’s not singling me out, but my back is still up.

Why is she asking me? What do I say?

Dad’s mum came from Jamaica and married an Irish man she met five minutes from where we live now, and Mum’s dad was French and married an English woman he met when she put a plaster cast on his broken arm. Where do I stand on this? To be honest it’s not something I ever really think about. We don’t talk about it at home. I know that I’ve never felt English, but I’ve never really felt Jamaican or French or Irish either. We’re from Birmingham. The one time we went abroad as a family, to Corfu, a girl from Belgium asked Marc where he was from and that’s what he said. The girl asked what country and Marc just smiled and said Birmingham was enough.

Louise changes her approach. “Question is,” she says, “should there be one rule for people born in a country and one for those who’ve come from somewhere else?” and the eyes on me are getting hotter.

What the hell is her problem?

I don’t know, Miss. Probably not. I don’t care. Ask someone else. Everybody’s shit stinks. I try not to hear it. Say it. My teeth grind together.