Полная версия

Floyd’s India

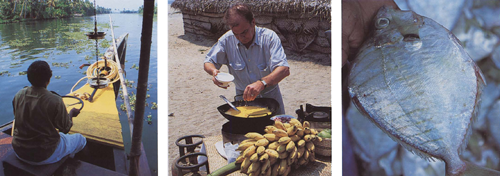

Opposite India’s opening batsman, Lords 2012… Below left to right Floating down the backwaters. Cooking on the beach. At the fish market.

Give a man a fish and he will live for a day, teach a man to fish and he will live forever. Chinese proverb. Chinese nets, Fort Cochin.

Goa

From Kerala we went north–to Goa. There we had a lot of fun on our brief visit. We stayed at the Taj Fort Aguada beach resort where we were given a fabulous bungalow which had been built, along with several others, specifically for visiting heads of state for a Commonwealth conference some years previously. I was quite tickled to be given the bungalow that Mrs Thatcher had stayed in. This was the second time our virtual paths had crossed. The last time was in the bodegas (cellars) of Gonzales Byas in Jerez, Spain where I was invited to sign a barrel in the hall of fame adjacent to a barrel signed by Mrs T. Please note this is not a sign of my political leanings in any sense of the word, but I think it is about time she came back as the President of Great Britain.

Goa is a tropical idyll with superb sandy beaches, which have made it a favourite winter sun destination. Colva Beach, 25 kilometres of pure white sands, is one of south Asia’s most spectacular beaches. The beaches are, however, only part of the picture. Inland is a lush patchwork of paddy fields and coconut, cashew and areca plantations. Further east are the jungle-covered hills of the Western Ghats and the drier Deccan Plateau. The Dudhsagar waterfall on the Goa/Karnataka border is the second highest waterfall in India — 600 metres from top to bottom.

The tiny state of Goa feels quite different from the rest of India, due to the fact that for 451 years, while the rest of India was under Mogul and British rule, Goa was a Portuguese stronghold. The influence of the Portuguese occupation is plain to see through the charming brightly painted villas and farmhouses in the pretty towns and villages. It is this southern European influence that is said to account for the difference in the general attitude of its people and the food that they eat. Wherever you go, you can find traces of Portuguese domination. The food blends a Latin love of meat and fish with India’s predilection for spices. Goans add vinegar to many dishes, giving them a very distinctive flavour. Alcohol is also prevalent — more than 6,000 bars around the state are licensed to serve alcohol, including the local brew, Feni, a rocket fuel spirit distilled from coconut sap or cashew fruit.

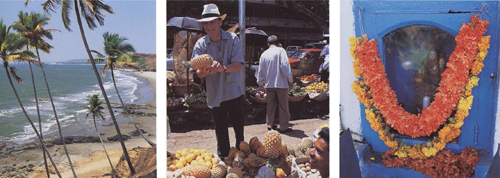

Below left to right One of the many beautiful beaches in Goa. Panjim market. Marigolds in the Latin quarter.

Away from the coast are the ruins of the Portuguese capital Old Goa, a sprawl of Catholic cathedrals, convents and churches that draws Christian pilgrims from all over India. Soaring above the canopy of palm groves, the colossal, cream cathedral towers, belfries and domes welcome you to one of the finest groups of Renaissance architecture in the world. Further inland, the thickly wooded countryside around Ponda harbours numerous temples. Spices have always been one of the area’s principal exports, even before the Portuguese arrived, and there are several large spice plantations around Ponda that can be visited.

Festivals celebrated in Goa include Id-ul-Fitr, in January/February, a Muslim feast to celebrate the end of Ramadan; the carnival in February/March, which is three days of Feni-induced mayhem, and Shigmo, held in February/March. This is Goa’s version of the Hindi holy festival held over the full moon period to mark the onset of spring. It includes processions of floats, music and dancing, as well as the usual throwing of paint bombs.

In Goa it is quite funny to see that the pony-tailed, bandanna-wearing flower children of the sixties are now in their sixties and still having a ball, although the pony tails have turned grey or indeed white. It was here that we met a couple of excellent eccentrics, Derek and Beryl — he a retired stockbroker of the old school, and Beryl who was just lovely, kind, cheerful and totally passionate about India and the Indians. They spent six months of every year travelling throughout India. Because they were such long-standing guests of the hotel, they were accorded all kinds of privileges, one of which was an outrageously delicious mango chutney sent down from Mumbai specifically for their use. So, every night we would meet for evening tiffin — I don’t care what you think tiffin is, as far as I am concerned it’s a large Bombay Sapphire gin with tonic and fresh lime — and devour a pile of freshly made poppadoms covered in the best chutney I have ever tasted.

Oh, and by the way, talking about food, I recommend to you two great Goan dishes, the Goan lobster curry and the beef or chicken vindaloo, a dish that bears no relationship to the ones that we all used to eat with a belly full of beer on Saturday nights many years ago.

Betim fish market.

Madras (now known as Chennai)

Back in the sixties in England, office dress code was relaxed on Saturdays and you could do your morning’s work wearing a sports jacket or a blazer instead of the Monday-to-Friday suit. Chaps tended to wear their sports club ties and hastened quickly through their desks to be in the White Elephant by 12.30pm. They stood in their dozens, kit bags at their feet, foaming pints in hand. Boys drank I.P.A., the men drank Worthington E. Objective: to down as many pints as possible before piling into old bangers or shiny M.G.s and heading for one of the many Bristol Combination Rugby Football grounds where, in the amicable brutality of Club Rugby (Bristol Combination style) they would, in the hot and sweaty scrum, gag on the Worthington-flavoured farts, throw up at half-time, eat an orange and have a quick drag on a Senior or a Nelson.

After you had lost and taken the communal bath, diplomatic relations were restored between the two sides. Bruised and broken, as one they piled back into the motors and headed off to the memorial ground to watch the last 15 minutes of Bristol thrashing Cardiff or Llanelli, Harlequins or Coventry and, clutching more pints, you would wonder why Bill Redwood and John Blake had not been selected for the England side. As time went by, the bar got hotter, tales of Rugby daring got louder, pints were spilt, voices were raised, and birds were eyed but not pulled because they were for the great men of the Bristol 1st XV.

In those, some say, halcyon days, Bristol was in Gloucestershire and the pubs shut at 10.30pm, but, minutes away, across the Clifton suspension bridge was Somerset, where the splendid hostelries stayed open until 11.00pm and there was the possibility that the landlord might just serve one more after time as he rang the bell. Everybody, by now, was in complete disarray. Everybody had probably drunk between 10 and 20 pints of beer since the first dignified pint in the White Elephant. Two or three would have fallen by the wayside, quite literally; some of the sensible ones would have returned to their wives, but the single guys were hungry. A leader always emerges at a time of crisis. It was the one who stood on the table, pint in hand, tie unknotted, shirt undone, who, bright eyed and sweating, called out ‘Who’s for the Curry House?’ And so, once again, we piled back into the vehicles, more crowded than before because one or two had disappeared, and headed back over the Clifton suspension bridge, down to the city centre, past the bus station and along to Stokes Croft where a flickering yellow neon sign announced the existence of the Koh I Noor Indian Restaurant.

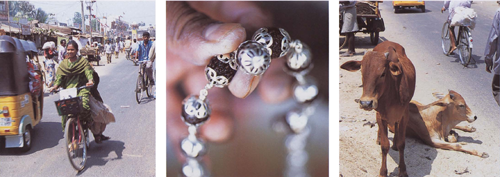

Below left and right Images from Madras. Middle Cleaning silverware.

Inside the dining room, with its 14 tables standing on a slightly sticky, thick carpet, each table had a slightly soiled but very starched tablecloth. The walls were covered in tawdry flock and the exhausted waiters, in their stained dinner jackets which were almost a deep, dark green through years of wear, adjusted their clip-on bow ties and prepared for the onslaught. They had an air of resigned acquiescence. Each table was dressed simply with a salt and pepper pot and a stainless steel sugar bowl filled with white sugar lumps. The call was for–because that’s all there really was — six chicken vindaloo, nine meat Madras, four plates of evil smelling, deep-fried, crispy Bombay duck and mango chutney and, of course, 15 pints of lager. The bewildered waiter wrote the order on a series of little duplicate pads and headed for the kitchen only to be called back by the blue-eyed fly-half with crinkly blond hair, who was training to be an accountant, and from his position of authority on the main table he would say, ‘Make that 30 pints.’

Eventually, on white plates, the pungent curries and mountains of plain boiled rice arrived. There was, of course, not enough cheap stainless steel cutlery to go round. The Madras was hot, fiery and acrid, the vindaloo was diabolical. One by one, chaps would go to the bog but, one by one, they didn’t return because the old hands knew that you could climb out of the window and then you wouldn’t have to pay your share of the bill. So, every Saturday night was a mad Madras night.

Well, dear reader, that was in another time. It was before Indian restaurants became a culinary force to be reckoned with, before silver leaf garnished fragrant biryanis. It was before Britain had ever heard of a tandoor oven, but it was at a time not so long after India gained independence from Great Britain and the country was still awash with ex-colonials who wanted to continue eating their meat Madras or chicken Madras and their Bombay duck. In reality, the concept of a meat Madras is entirely a figment of the British imagination, but that is something I learnt much later in life.

In the meantime, and hoping to fulfil some kind of youthful gastronomic holy grail, I left the west coast full of anticipation for my visit to Madras. But, they’ve changed the name! Yes, okay, Madras was the first important British settlement in India and yes, quite correctly, the Indians have given it back its original name, Chennai, but how can you now go into your favourite curry shop after a hard game and say, ‘9 meat Chennais and 30 pints of lager, please’?

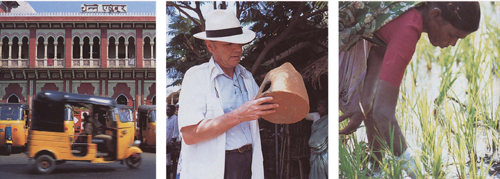

Above left to right Taxis Madras-style. A little wood burner. In the paddy fields.

Chennai is India’s fourth largest city, the capital of Tamil Nadu. It is a young city by Indian standards. Its foundation in the 17th century by the East India Company also marked the foundation of the British empire. When the fortification — called Fort St George — was completed in 1640 the walls protected the East India Company’s factory and other European trading settlements. Its function was to serve as a base for British agents to prevent local merchants controlling the price of goods. It later became the city of Madras. As it grew, the local Tamil people assigned the name Chennai to the city, whereas the British stuck to Madras. In recent years, however, it has been decided that the official name of the city should be Chennai.

The city is the home of curry powder, which was originally developed in Madras for the nostalgic British wishing to re-capture the flavours of India after they returned home from the Raj. Huge quantities of curry powder are still manufactured in machines that resemble concrete mixers, but it is all for export. No Indian cook would dream of using it.

British buildings dominate the area. The Ice House was built to store ice imported from Boston until it was used to cool the gin and tonics of the British residents. The Madras Club was built as a place where the British elite could drink the G & Ts. The chief reminder of colonial days, however, is the High Court, the largest court of law building in the world outside London. To the south, 20 hectares of narrow lanes form the city’s largest market, Kothawal Chavadi, which includes a colourful fruit and flower section. On the outskirts of the city is Asia’s biggest film studio complex, just beyond the jaws of a fake shark which guards MGR Film City. On this enormous site, funded by the state government, are 36 sets standing ready for use. Tourists are sometimes invited to be extras, especially in Raj-era films.

Now, in the intervening 40 years between eating my first meat Madras and my first visit to Chennai, I have learned a lot and I certainly was not expecting to find an authentic meat Madras in Madras, any more than I would expect to find a spaghetti Bolognese in Bologna or a chop suey in Beijing. These, and many other internationally known dishes are, again, concoctions created by bewildered ex-patriots. I did, however, expect to find exquisite food, but I was disappointed. As with all big cities the world over, it is hard–not to say nearly impossible–to find the gastronomic heart of that place. I stayed at the Connemara Hotel where they had a specialist restaurant devoted to the Chettinad cuisine, which is fiery, hot and spicy and should be delicious, but it was not.

Away from the crowded streets.

Using all the resources available to me, I sought out the so-called good restaurants but, quite frankly, you will probably eat better in Southall or Birmingham, and that is not to mention how hard it is to put up with the inexorable poverty and squalor which gives birth to begging and harassment. So then you have to ask yourself, if you are finding this so offensive, why are you here in the first place. Well, the fact is the cooking in India can be one of the great experiences of life but it is best enjoyed at the home of Indians, no matter how rich or poor they might be. They treat their produce with such love and such care. They prepare their masalas with the same sort of love with which Van Gogh must have mixed his oils.

I spent some time at a magnificent palace where a family of four or six people were attended by over two hundred staff. The dichotomy lies in the fact that the poor can’t afford to eat in restaurants, so there are just absolutely fundamentally basic squalid soup kitchens, while the rich are so well off they can afford to have cooks at home, so no matter what you read in the otherwise absolutely essential Lonely Planet Guide to India, take their restaurant entries with a pinch of chillies.

If you do eat in the streets of any of the big three cities, Chennai, Calcutta and Mumbai, and you choose a place which is very, very busy, you will usually eat well for a few pennies, cents or dimes.

However, if you are in Chennai, make a point of eating at Hotel Saravana Bhavan. This is the ultimate in Indian fast food restaurants. They have a menu of over three hundred different dishes, mostly vegetarian. They serve up to 4,000 meals a day (by the way, it is not a hotel, the word ‘hotel’ in many parts of India means restaurant or canteen). You get a tray on which are eight, nine or ten little dishes, savoury, sweet, hot, sour. It is called a thali and the first person who replicates this brilliant concept (in many ways not dissimilar to Spanish tapas) in London will make a fortune and change the gastronomic mindset of a nation already obsessed with Indian food. Anybody prepared to put several million quid into my idea can buy not only my expertise, my knowledge and my passion but they will also have the exclusive rights to the name of this amazing chain of eateries and, with due apologies to Paul Scott, it will be known as ‘The Last Days of the Floyd’.

We ground out of Chennai through the appalling traffic to the village of Sriperumbudur where, from a distance, you can see water buffaloes bathing and high-rise ancient temples which, if you squint, remind you of Gotham City. We saw the ancient reservoirs, so-called tanks, where the lepers cleanse themselves and the locals do their washing, but it ain’t like a visit to Salisbury Cathedral!

It was quite funny on the day that we all went there to film what is actually a very beautiful and fascinating place. On the way my beloved director, Nick, somehow got it into his head that the Indians grow a lot of rice and we should acknowledge that fact in our telvision programme. You have to remember, however, that there is nothing real in television land. Some 30 or 40 hapless Indian women were planting rice in a paddy field but, quel horreur, on the shady side of the field. This is, of course, totally unacceptable; for television purposes they must be in the sunshine to avoid shadows, so that the colours are bright and vibrant. To make matters worse, it was impossible to get a shot of these people from the road because the camera angle would not be correct. So, at the behest of Nick, our long-suffering researcher, Raj, was instructed to tell the semailleurs — which is French for seed sowers–to move over to the other side of the field and replant what they had already planted for the benefit of our camera. In the meantime, Stan, my manager, on this day dressed in combat kit, drawing on a cigar and for all the world looking like Stormin’ Norman, hijacked and occupied the adjacent hospital. He stormed the operating theatre, where bewildered surgeons were bullied into allowing him–in mid-operation–to place the camera on the roof so that the world could see something that they have probably never seen before, since the dawn of television, a load of women planting rice.

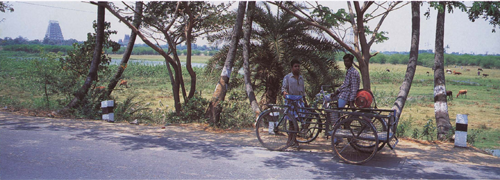

Sriperumbudur Temple and Tank.

Above left to right One of the many temples at Kanchipuram. Bogged down at Muttukadu.

Interlude at Kanchipuram

Some 40 or 50 minutes out of Madras there is a splendid Taj hotel called Fisherman’s Cove at Covelong Beach, near Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu. The beaches are unspoilt, there are spectacular views, regular rooms in the hotel complex and utterly enchanting guest bungalows on the beach. Here, with Tess, I spent six magnificent days as the guest of Sarabjeet Singh, the general manager. During that time I learnt how to make some exquisite dishes, including the subzi poriyal (crunch spicy beetroot with coconut) and kathirikai kara kulambu (a spicy aubergine dish) on pages 153 and 156, from the hotel’s executive chef, Fabian. I seem to remember he had a couple of hits in the charts in the late fifties. (Joke! Rock-’n-rollers know what I mean.)

Kanchipuram is the Golden Town of 1,000 Temples, one of India’s seven most sacred cities. Nowadays only 126 temples survive, but five of these are considered outstanding. They are closed between noon and 3.00pm and are best visited in the afternoon. On the same stretch of coastline as Covelong Beach is the famous Shore Temple at Mamallapuram, probably the best-known sight in southern India.

A Bombay market.

Bombay (now known as Mumbai)

So, on a high from the Fisherman’s Cove, our culinary circus rolled on to Bombay (or Mumbai as it is now known), birthplace of Rudyard Kipling in 1865, and a city famous for its red double-decker buses. Home of the wealthy and glamorous, Mumbai is the commercial hub of India. Here there is a huge contrast between the rich and the poor. The city claims more millionaires than Manhattan, and there is indeed an almost ostentatious display of wealth, and yet two million people in the city do not have access to a toilet, six million go without access to drinking water and over half the city’s population of 16 million people live in slums or on the street.

The huge natural harbour is the reason why commerce blossomed in Mumbai, helped by the opening of India’s first railway line which started in Mumbai. Elephanta Island in the middle of the harbour has magnificent rock-cut cave temples, one of the city’s main tourist attractions, and in February a festival of music and dance is held at these cave temples.

Mumbai is also the home of Bollywood, the Indian version of Hollywood, which produces more films than any other city in the world — 120 feature films per year. In Mumbai you can still savour the glamour attached to the notion of going to the movies at one of the glorious art deco cinemas.

The Gateway of India.

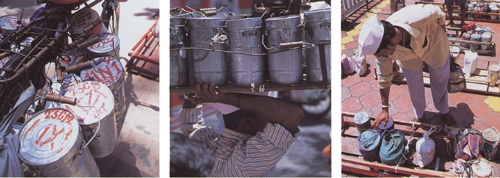

Above left to right Lunch box delivery.

The city also has over 50 laughter clubs. Members gather in parks all over the city each morning and laugh themselves silly, in the belief that happiness and health are connected and drawing on ancient yogic texts that highlight the beneficial effects of laughter.

Mumbai has a unique lunch service. Hot lunches are delivered to workers in their offices direct from their homes by something akin to a postal service. Before noon, dabbas, ever-hot lunch boxes, containing a home-cooked meal are collected from residencies by dabbawallas. They are sent to the city by train and dropped at various stations for lunchtime delivery by other teams of dabbawallas. Ownership and location of each lunch box is identified by markings decipherable by the dabbawallas alone. After lunch the whole process is reversed.

Crawford Market and the bazaars of Kalbadevi and Bhuleshwar sell everything from mangoes to tobacco to Alsatian puppies; if you can eat it or stroke it, you can probably find it here.